Endovascular Treatment of Acute Iliofemoral DVT

RAFAEL D. MALGOR and ANTONIOS P. GASPARIS

Presentation

A 35-year-old female, otherwise healthy, with a 17-pack-year history of smoking presents to the emergency department complaining of left lower extremity pain and swelling over the past 2 days. She states that 3 days ago, she returned home from her summer vacation in the New England region and had to drive herself back home for about 6 hours. She also informs you that she has been taking oral contraceptives for about 15 years, but no other medications. She denies any chest pain, history of similar episodes of lower extremity edema, any trauma, or long bone fractures in the past. Her vital signs are within normal limits except for an elevated respiratory rate. She appears to be uncomfortable holding her left thigh and calf that is notably more swollen compared to the right. Her left distal thigh, calf, and foot are cyanotic, and multiple engorged, nonvaricose veins are noticeable. Due to significant edema, pedal pulses are difficult to palpate, but are present. She denies any foot numbness, and she is able to flex and extend her ankle and toes that elicits calf pain. Noteworthy, her mother and one of her aunts had vein stripping in the past and her paternal uncle had an episode of cardiorespiratory collapse that was related to leg swelling.

Differential Diagnosis

Lower extremity pain associated or not with edema can be caused by several entities. One must always investigate if the patient had any recent trauma that could have caused a muscle tear, soft tissue hematoma, or bone fractures. A ruptured Baker’s cyst should be considered regardless of the evidence of fall or body collision. Traumatic injuries are often suggested by localized tenderness and edema of a specific affected portion of the lower extremity. Patients with history of travel to mountains or forest or those who practice hiking must also be asked about any insect bite or skin tear that can be related to infectious process. It is not rare to have a patient with signs of initial necrotizing fasciitis caused by a bug bite or skin excoriation. A warm, hyperemic leg coupled with some signs of sepsis, such as fever and chills, is not always present but definitely helps to differentiate an infected leg from other causes.

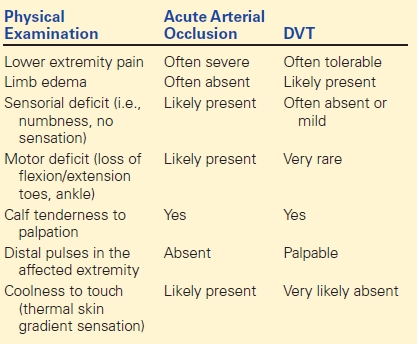

The most important differential diagnosis to be excluded in any patient with acute onset of leg pain is acute limb ischemia that has to be addressed in a timely manner in order to ultimately avoid devastating consequences, such as limb loss. This particular patient has some findings that aid to a diagnosis other than acute arterial occlusion. On the physical exam, the patient has palpable pulses. Further, when evaluating the motor and sensory status of the limb, the physician also noted a completely intact neurologic exam that is often present only in very initial stages of acute arterial occlusion. A quick review of symptoms of acute arterial occlusion and deep venous thrombosis is provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Typical Clinical Presentation of Acute Arterial Occlusion and DVT

The presence of risk factors such as a long car ride, use of oral contraceptives, tobacco use in a female patient coupled with positive findings of asymmetric limb edema, pain, enlarged nonvaricose veins, palpable pedal pulses, and intact neurologic function makes the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) very appealing. However, DVT diagnosis is difficult to be made based only on physical exam findings that have low sensitivity and specificity as many conditions can mimic the signs and symptoms of DVT. Thus, an imaging study must be obtained in order to confirm the DVT diagnosis.

Workup

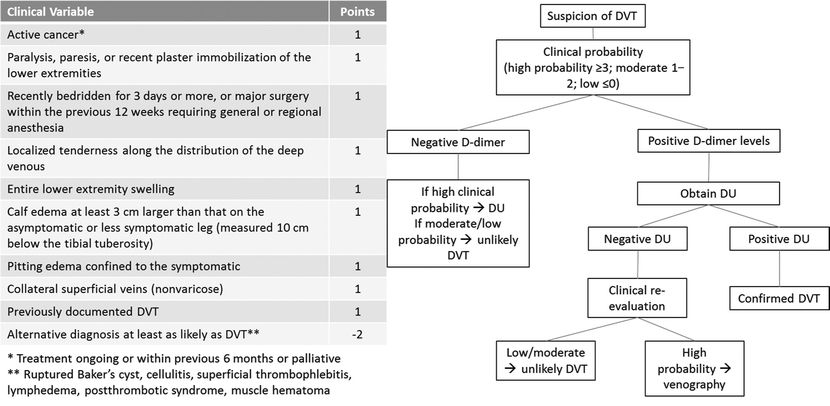

In the emergency department, a quick assessment using a clinical DVT probability score (Wells’ criteria) plus measurement of d-Dimer levels can potentially rule out DVT before any imaging study or vascular specialist consultation is requested. The Wells’ criteria, their interpretation, and decision-making algorithm are summarized in Figure 1. It is important to note that in many patients, d-Dimer is falsely positive, and therefore, such patients should not be tested. Also, those patients with high probability for DVT should not have d-Dimer test but an imaging test.

FIGURE 1 Simplified algorithm to triage patients with suspicion of DVT based on Wells’ criteria.

The first and most important step in the workup for lower extremity venous thromboembolism is the duplex ultrasound (DU). DU has many advantages over other imaging studies because it is a low-cost, portable, safe to use, easy to repeat, and noninvasive tool. Evaluation of the suprainguinal veins is at times necessary such as when thrombus extends to the level of the common femoral vein or when there is suspicion of pathology above the inguinal ligament. This can be achieved with DU, but when the suprainguinal veins cannot be clearly evaluated, computed tomographic venography (CTV) or magnetic resonance venography (MRV) can be obtained to further delineate the extent of DVT and patency of inferior vena cava (IVC).

In this particular scenario, iliac vein compression must be considered. May-Turner syndrome occurs when the left common iliac vein (CIV) is compressed by the right common iliac artery (RCIA) and often affects female patients. Other iliac vein compression syndromes have been described including right common iliac and external iliac vein (EIV) compression.

Imagining Workup (DU/CTV)

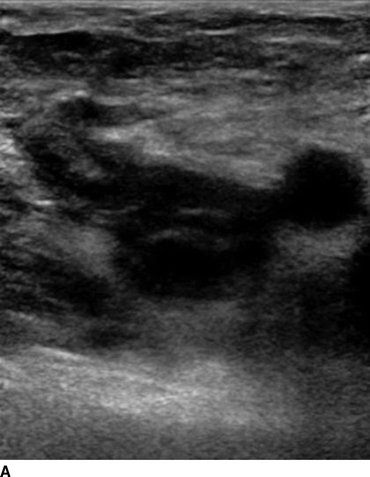

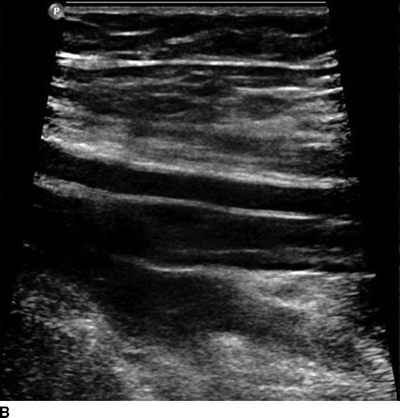

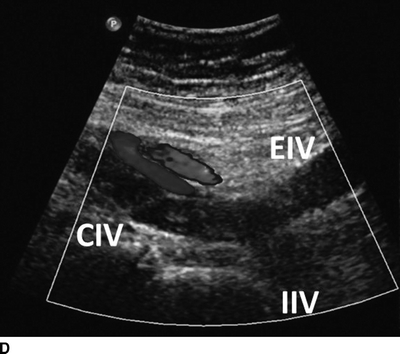

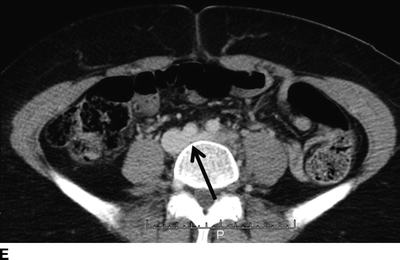

Intraluminal echolucent material is seen in the left popliteal and femoral veins extending into the EIV. The veins are dilated and noncompressible and have no flow augmentation. Additionally, a reduced diameter is noted in the proximal CIV with thrombosis of CIV and external and internal iliac veins (Fig. 2A–D). A CTV is obtained confirming that the IVC is widely patent, and the left CIV is compressed by the RCIA (Fig. 2E).

FIGURE 1 A: Left acute femoral vein DVT. B, C: Note the involvement of the deep femoral and popliteal vein (acute thrombosis). D: DU showing extensive left iliac vein thrombosis (CIV, common iliac vein; EIV, external iliac vein; IIV, internal iliac vein). E: Compression of left CIV by the RCIA is demonstrated on CTV (arrow).

Diagnosis and Treatment

The diagnosis is acute iliofemoral DVT, which was confirmed by DU. Treatment options for this patient include anticoagulation, thrombolysis, and surgical thrombectomy. The latter is only indicated in patients with impending venous gangrene or contraindication to thrombolytic therapy. Thrombolysis is appealing due to early thrombus resolution, preservation of valve function, and possibly lower incidence of postthrombotic syndrome. Thrombus lysis can be accomplished locally, directed through a catheter (catheter-directed thrombolysis, CDT) or combined with a device that performs mechanical thrombectomy (pharmacomechanical thrombectomy, PMT). Systemic thrombolysis has been abandoned due to its significant risk of bleeding complications and inconsistent efficacy.

Several studies comparing anticoagulation versus CDT have demonstrated superior recanalization rates in patients who underwent CDT. The ongoing experience and excellent results of PMT have also been reported with lower dosage of thrombolytic, less duration of treatment, and lower bleeding complications.

Patient selection for thrombolysis is very important and includes presence of contraindications, patient comorbidities, and age of thrombus. Absolute contraindications to thrombolysis include history of previous intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), arterial puncture at a noncompressible site, intracranial neoplasm, cerebral arteriovenous malformation or aneurysm, recent intracranial or spinal surgery, uncontrolled blood pressure (systolic greater than 185 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure greater than 110 mm Hg), active internal bleeding, or any acute bleeding diathesis (i.e., platelet count less than 100,000/mm3). The 9th edition of the Chest Guidelines indicates that venous thrombolysis is most likely to be beneficial in patients with iliofemoral DVT with symptoms for less than 14 days, good functional status, life expectancy of greater than 1 year, and a low risk of bleeding. It remains to be further investigated whether or not thrombolysis in patients with femoropopliteal DVT, thrombus greater than 14 days, and the use of PMT in patients with higher risk of bleeding (i.e., isolated segment thrombolysis with Trellis device) can improve clinical outcomes.

Case Continued

An informed consent including the potential risks, such as major bleeding, pulmonary embolism, and death, and the benefits of resolving or diminishing the clot burden is obtained. A blood sample is drawn to determine the baseline of fibrinogen levels, platelet count, hematocrit and hemoglobin levels, activated partial thromboplastin, and prothrombin time.

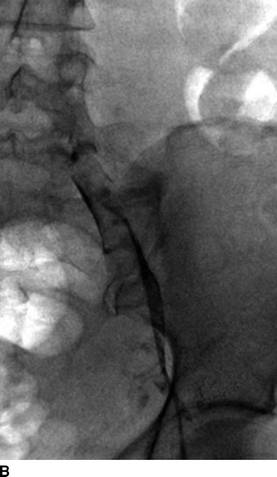

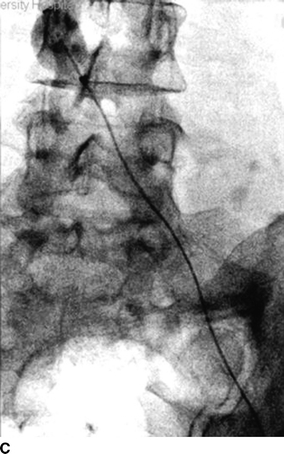

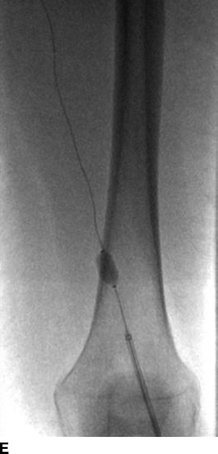

The patient is taken to the interventional suite or operating room, prepped, and draped in the prone position. A direct popliteal vein ultrasound-guided puncture is then performed using a micropuncture needle, wire, and catheter, which is subsequently exchanged by a 4-Fr sheath over a hydrophilic wire. An initial venogram is obtained, which in this patient shows filling defects in the entire femoral vein extending into left iliac veins (Fig. 3A and B). Then, an angled glide wire and glide catheter are advanced into the IVC. Venogram of the IVC demonstrates that it is patent. A 30-cm long Trellis catheter (Trellis-8 Peripheral Infusion System, Covidien, Mansfield, MA) is chosen and parked in the entire length of the thrombosed left iliac veins. The proximal balloon is inflated in the IVC and pulled back to the origin of the left CIV (Fig. 3C). The distal balloon is inflated in the femoral vein, isolating the treatment segment (Fig. 3D). Infusion of r-tPA through the Trellis catheter allows lysing the thrombus during the treatment cycles. Following treatment of the iliofemoral segment, the femoropopliteal segment is treated in a similar fashion with distal balloon now inflated in the distal femoral vein (Fig. 3E). A completion venogram is obtained showing patent proximal iliac veins with compression at the level of left CIV (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 3 A: An initial venogram showed thrombosis of the left femoral vein. B: Extensive involvement of left iliac veins is also noted. C: PMT is initiated using a 30-cm-long Trellis catheter (Trellis-8 Peripheral Infusion System, Covidien, Mansfield, MA). Note that the proximal balloon is inflated in the IVC and then back off to engage the proximal CIV. D: The distal balloon is initially parked in the femoral vein isolating the treatment segment. E: After treating the iliofemoral segment, the distal balloon is parked in the transition between the femoral and the popliteal vein to complete the treatment.