Chapter 25 Electrophysiological Evaluation of Ventricular Fibrillation

Introduction

Sudden cardiac arrest accounts for between 300,000 and 400,000 deaths in the United States alone each year. Although the underlying pathophysiology for the majority of these deaths is coronary artery disease (CAD), in autopsy studies, evidence of recent occlusive coronary thrombus is present in only up to 64% of patients.1 Thus up to one third of all cases of unexplained sudden cardiac arrest may be primarily caused by cardiac arrhythmias, with ventricular fibrillation (VF) being the culprit arrhythmia in the majority of patients. Although secondary and primary prevention trials have demonstrated the superiority of implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) compared with antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) in preventing death, which represents ICD therapy as the gold standard treatment for this condition, current methods of risk stratification are primarily based on the assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).2,3

Programmed Ventricular Stimulation

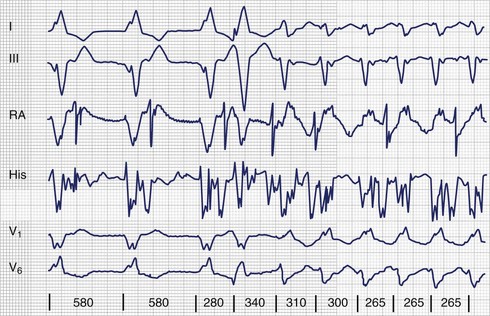

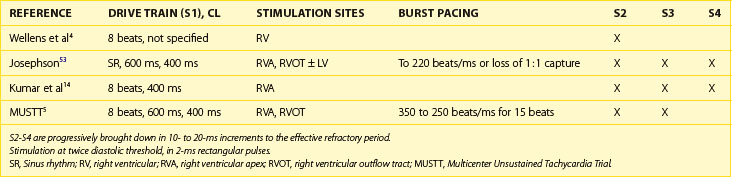

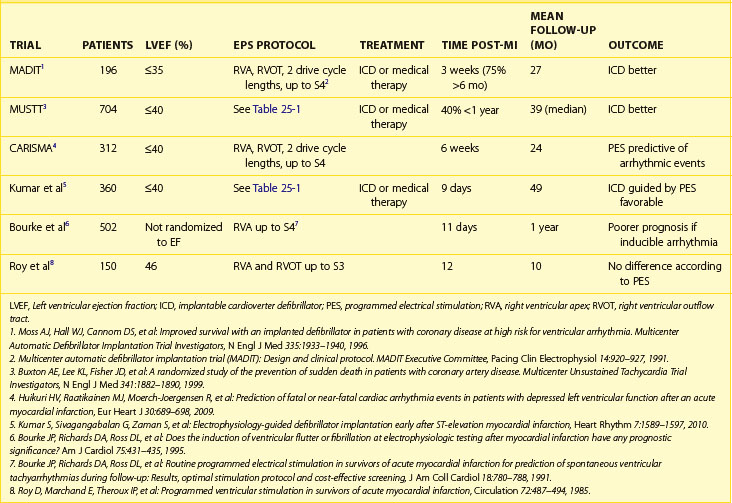

The use of invasive electrophysiological study (EPS) to risk stratify patients goes back almost 40 years to the observation by Wellens et al that in patients with prior myocardial infarction (MI) and ventricular tachycardia (VT), programmed ventricular stimulation could be used to induce the same VT (Figure 25-1).4 Although the sensitivity of programmed ventricular stimulation has been refined since its original description, a nonclinical ventricular arrhythmia is induced in approximately one third of patients.5 Although protocols vary among institutions, stimulation is normally performed from both the right ventricular apex and the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT). Initially, single, double, and then triple extrastimuli are applied to a sensed ventricular beat, reducing the last extra stimulus by 20 ms each time until the effective refractory period (ERP) is reached. An eight-beat drive train is then followed by a single extrastimulus, then two and finally three extrastimuli, with the coupling interval of the last extrastimulus being decreased by 10 or 20 ms until the ERP is reached for the first extrastimulus. Typically, 600-ms and 400-ms drive trains are used. Most operators stop extrastimuli at a coupling interval of 180 to 200 ms because with shorter coupling intervals, the specificity of the test is reduced and polymorphic VT and VF occur more frequently.6 However, recent work suggests that patients with VT of a cycle length 200 to 250 ms are at high risk of a subsequent event and that this should not be taken as a nonsignificant event in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy (Table 25-1).7

Ischemic Heart Disease

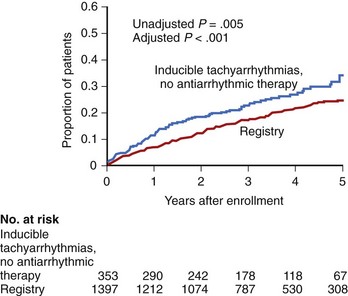

The Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial (MUSTT) was a multi-center prospective study that enrolled 2202 patients with significant CAD, reduced LVEF (<40%), and nonsustained VT and subjected patients to programmed ventricular stimulation.8 VT was induced in just over one third of patients. These patients were then randomized to either no AAD therapy or AAD therapy guided by repeated stimulation. If VT remained inducible despite AAD therapy, an ICD was implanted. Patients in whom sustained monomorphic VT was induced were monitored by a registry. Although this study confirmed that patients with inducible VT off AADs had a higher rate of arrhythmic events over the following 5 years compared with those without inducible VT (36% vs. 24%; P = .005), the event rate in patients without inducible VT at the time of invasive EPS was not insignificant (Figure 25-2).9

As just stated, it is not uncommon to induce polymorphic VT and VF at shorter extrastimulus coupling intervals and with multiple extrastimuli. In the MUSTT trial, induction of polymorphic VT or VF was considered positive only if this occurred with up to two extrastimuli. In a retrospective analysis of the Multicentre Automatic Defibrillator Trial II (MADIT-II), for which patients had to have an LVEF less than 30% and a prior MI, programmed ventricular stimulation was prognostic only when a positive result was taken—that is, not when polymorphic VT or VF had been induced with aggressive pacing.9,10 Although many studies were performed on acute arrhythmia suppression with AADs, the long-term use of AADs to prevent VT and VF has been disappointing, and it is now common to implant ICDs in patients at risk. However, this is mainly based on the patient’s LVEF, not on invasive testing.8,9,11,12

Current guidance for the use of programmed ventricular stimulation is based largely on the MADIT-I and MADIT-II trials and the results of the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT).11–13 In the United Kingdom, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence updated the guidelines for ICD implantation, which are used in other health care systems throughout the world. These evidence-based guidelines suggest that the role of programmed ventricular stimulation in the decision to implant an ICD is restricted to patients with a previous MI (>6 weeks), an LVEF of 30% to 35%, a lack of New York Heart Association (NYHA) class IV symptoms, and nonsustained VT on monitoring. These criteria were derived from the enrollment criteria to the MADIT-I study. Patients who were enrolled in the MADIT-II study with an LVEF less than 30% did not need to undergo invasive EPS. Although it appears that programmed ventricular stimulation has quite a narrow indication in the decision of when to implant an ICD, it still remains a useful tool. The absolute benefit from ICD implantation in the MADIT trial was 12% per year in which patients had to have a “positive” test result compared with a more modest absolute benefit of approximately 3% and 1.5% per year, respectively, in the MADIT-II and SCD-HeFT populations, in whom programmed ventricular stimulation was not used to determine ICD implantation.

On the basis of the MUSTT trial results, patients with clinically significant CAD and an LVEF of 30% to 40% and nonsustained VT would also benefit from ICDs if they had a positive programmed ventricular stimulation test result.8,9 Again, a large absolute benefit was demonstrated in this patient population, although for most patients the clinically significant CAD was a prior MI.

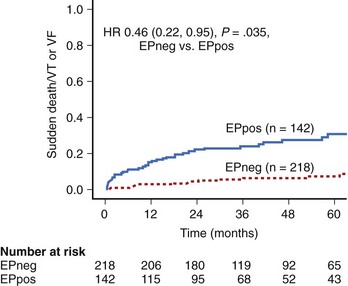

A recent study has shown that performing programmed ventricular stimulation may be beneficial when patients presented within the first few weeks after an MI and with an LVEF of less than 40% (Figure 25-3).14 ICD implantation is not routinely considered in these patients as a result of the Defibrillator in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial (DINAMIT), which demonstrated that patients with an ICD implanted within the first month of an MI with an LVEF of less than 35% and depressed autonomic function, as assessed by heart rate variability, actually had a worse outcome.15 Although fewer patients died of arrhythmic events, the rate of nonarrhythmic death was substantially high. These data, as well as those from the Immediate Risk Stratification Improves Survival (IRIS) trial, which also investigated early implantation of an ICD in high-risk patients (as assessed by reduced LVEF <40%, depressed autonomic function, or nonsustained VT on Holter monitoring), demonstrated no absolute mortality benefit from implantation.14 This has led to the current situation in which high-risk patients do not receive ICDs after an MI.16,17

The results of MUSTT, taken together with the more recent work on early programmed ventricular stimulation after successful revascularization, suggest that programmed ventricular stimulation is a useful tool in risk stratifying patients with a reduced ejection fraction after MI (Table 25-2). Compared with signal-averaged electrocardiograms (ECGs) and LVEF, programmed ventricular stimulation is the best predictor of spontaneous ventricular arrhythmia late after MI in patients with reduced ejection fraction.18,19

Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy

The role of programmed ventricular stimulation in the risk assessment of patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (IDCM) is not well studied. Approximately 50% of patients with IDCM will have SCD caused by ventricular arrhythmia as opposed to progressive heart failure.20 Impairment of left ventricular function alone does not appear to be a specific marker for risk.11,21,22 In the Cardiomyopathy Trial (CAT), 104 patients with IDCM and an LVEF less than 30% were randomized to either medical or ICD therapy.23 This trial had a very low rate of β-blocker use, which makes interpretation more difficult in the contemporary era. Despite this, overall mortality was very low, and the trial was stopped early because of futility.

In the Amiodarone Versus Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator: Randomized Trial in Patients With Nonischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy and Asymptomatic Nonsustained Ventricular Tachycardia (AMIOVIRT), 103 patients were enrolled, but this trial was also stopped early after just over 2 years because of a failure to show any benefit of an ICD. Again, there was a relatively low mortality rate of 12%.21 Although the use of β-blockers was better, only 53% of patients were taking them at the time of the study. Invasive EPS was again not used to risk stratify patients. In the Defibrillators in Non-Ischaemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation (DEFINITE) trial, a much larger number of patients were enrolled compared with either CAT or AMIOVIRT, with similar inclusion criteria.22 In addition, a greater population was on optimal medical therapy, with 84% of the population on β-blockers and 86% on angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, although spironolactone was not then part of the standard therapy. However, patients were excluded if they had undergone invasive EPS within 3 months. Although implantation of an ICD led to a significant reduction in the rate of SCD (HR, 0.2), it did not lead to an overall reduction in death from any cause.

A smaller study did investigate the use of programmed ventricular stimulation in this patient population as well as the presence of nonsustained VT on ambulatory monitoring.24 Although more than 80% of patients enrolled in the study were taking β-blockers, fewer than one fourth of patients were taking β-blockers at the start of the study. With a stimulation protocol of a six-beat drive train with two or three extrastimuli from a single site, monomorphic VT was inducible in 7% of patients. The addition of the third extrastimulus increased overall inducibility, but this was caused by the induction of polymorphic VT, ventricular flutter, and VF. During a mean follow-up of just over 2 years, the positive predictive value (PPV) was poor at 29%. Although the negative predictive value (NPV) of programmed ventricular stimulation was high, there was a very low event rate in the overall study population.

A more recent study looked at inducibility of ventricular tachyarrhythmias and subsequent therapy from an ICD implanted for secondary prevention.25 By using a different stimulation protocol from the previous study, with four basic drive train cycle lengths, up to two ventricular stimulation sites, and up to three extrastimuli, the investigators found that induction of polymorphic VT or VF was more predictive of subsequent fast VT or VF events than if sustained monomorphic VT was induced. They also found that these patients had a worse overall mortality rate despite having a similar left ventricular systolic function.26 However, this was a retrospective study, and the data collection took place over a long period, from 1994 to 2007, limiting the clinical application of this study.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree