The dual endothelin receptor antagonist, bosentan, has been shown to be well tolerated and effective in improving pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) symptoms in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome but data from longer-term studies are lacking. The aim of this study was to retrospectively analyze the long-term efficacy and safety of bosentan in adults with PAH secondary to congenital heart disease (PAH-CHD). Prospectively collected data from adult patients with PAH-CHD (with and without Down syndrome) initiated on bosentan from October 2007 through June 2010 were analyzed. Parameters measured before bosentan initiation (62.5 mg 2 times/day for 4 weeks titrated to 125 mg 2 times/day) and at each follow-up (1 month and 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months) included exercise capacity (6-minute walk distance [6MWD]), pretest oxygen saturation, liver enzymes, and hemoglobin. Data were analyzed from 39 patients with PAH-CHD (10 with Down syndrome) who had received ≥1 dose of bosentan (mean duration of therapy 2.1 ± 1.5 years). A significant (p <0.0001) average improvement in 6MWD of 54 m over a 2-year period in patients with PAH-CHD without Down syndrome was observed. Men patients had a 6MWD of 33 m greater than women (p <0.01). In all patients, oxygen saturation, liver enzymes, and hemoglobin levels remained stable. There were no discontinuations from bosentan owing to adverse events. In conclusion, patients with PAH-CHD without Down syndrome gain long-term symptomatic benefits in exercise capacity after bosentan treatment. Men seem to benefit more on bosentan treatment. Bosentan appears to be well tolerated in patients with PAH-CHD with or without Down syndrome.

Bosentan has been widely studied and used to treat patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with congenital heart disease (PAH-CHD). It is a dual endothelin receptor antagonist that blocks endothelin A and endothelin B receptors. In the Bosentan Randomized Trial of Endothelin Antagonist Therapy–5 (BREATHE-5) study bosentan was shown to improve exercise capacity and pulmonary hemodynamics in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome. Based on these data, bosentan is the only endothelin receptor antagonist currently recommended for treatment of Eisenmenger syndrome. Questions remain, however, over the sustained efficacy of bosentan in the mid to long term. Some studies have demonstrated sustained beneficial effects, whereas others have shown that beneficial effects of the drug decrease with longer-term use. We conducted a retrospective analysis of our database of all adults with PAH-CHD including Eisenmenger physiology treated with bosentan at our institution—a tertiary adult congenital cardiac center—to assess efficacy, safety, and tolerability in the medium to long term.

Methods

Data on all adult patients (≥18 years old, with and without Down syndrome) with PAH-CHD who were referred to and received PAH therapy at our tertiary adult congenital cardiac center were prospectively collected in a dedicated database.

Data recorded include patient demographics, underlying cardiac diagnoses, baseline medications, and hemodynamic, efficacy, and safety parameters. Before treatment initiation, all patients who give consent undergo right and left heart catheterization and hemodynamic parameters such as mean pulmonary arterial pressure and ratio of pulmonary to systemic pressure are measured. Where possible, exercise capacity (using the 6-minute walk distance [6MWD] test) and oxygen saturation levels at rest (using pulse oximetry or by blood sampling) are measured before bosentan initiation and subsequently at each follow-up visit. Owing to inherent difficulties in accurately assessing exercise capacity in patients with Down syndrome, 6MWD is analyzed only for patients without Down syndrome. Laboratory measurements of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and hemoglobin levels are measured before bosentan initiation and at each follow-up visit. Adverse events are recorded throughout treatment.

All patients initiated on bosentan from October 2007 through June 2010 were included in this retrospective analysis. Data collected up to December 2010 were analyzed. Bosentan was initiated at 62.5 mg 2 times/day for the first 4 weeks and was titrated up to 125 mg 2 times/day thereafter in all patients except 1 owing to tolerability issues.

Data were analyzed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Patients were included in the analysis only if they had a baseline (before bosentan initiation) and ≥1 postbaseline (after bosentan initiation) parameter. Categorical data are described by frequency and percentage; continuous data are summarized by their mean ± SD or median and range. Pretest oxygen saturation, 6MWD, AST, ALT, and hemoglobin were analyzed at all visits from baseline until treatment month 24 (i.e., baseline, months 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24.). Absolute and mean change from baseline values in 6MWD with no imputation for missing values and last observation carried forward (LOCF) imputation to account for missing values were analyzed. Predictors of change from baseline in 6MWD response to treatment were examined using repeated-measures multivariate linear random effects regression model, with baseline oxygen saturation, age, gender, ethnicity, and diagnosis as covariates. The same random effects models (with random intercept, slope, and quadratic terms), which does not impute for missing values or make LOCF assumptions, were also used to test for changes from baseline over time, with significance set at the p <0.05 level for all parameters. Absolute pretest oxygen saturation was summarized separately for patients with and without Down syndrome with and without LOCF imputation. Changes from baseline in oxygen saturation were analyzed by a repeated-measures linear effects regression model with random intercept. The relation between change from baseline in 6MWD and oxygen saturation level was examined for patients without Down syndrome using a graphical approach and quantified using Spearman correlation coefficient. For AST, ALT, and hemoglobin levels, data were summarized for all patients with and without LOCF imputation.

Results

The database included 39 patients with PAH-CHD, 10 of whom had Down syndrome, all having received ≥1 dose of bosentan. Three patients (1 with Down syndrome) were already on bosentan when referred to our center. Bosentan was initiated in all patients who were naive to other PAH-specific drugs, with the exception of 1 patient without Down syndrome who was already taking sildenafil 50 mg 3 times/day. In all but 2 patients bosentan was maintained as monotherapy; 1 patient was also given sildenafil 16 months after starting bosentan and another was given sildenafil 2 years 2 months after starting bosentan, which was subsequently discontinued owing to poor tolerability. One patient stopped taking bosentan for 4 months after 18 months of treatment because she wanted to start a family; however, subsequent symptomatic worsening prompted a decision to restart the drug. Patient demographics are presented in Table 1 . Most patients were on anticoagulant/antiplatelet therapies, principally warfarin or aspirin, and use of other cardiac drugs including β blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, and diuretic medications was common ( Table 2 ). Of the 8 patients on iron-replacement therapy, 6 were women.

| Variable | Patients Without Down Syndrome | Patients With Down Syndrome | All Patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 29) | (n = 10) | (n = 39) | |

| Age at treatment initiation (years) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 40.72 ± 14.25 | 32.70 ± 8.06 | 38.67 ± 13.32 |

| Median (range) | 36 (22–67) | 33 (22–49) | 34 (22–67) |

| Women | 18 (62%) | 5 (50%) | 23 (59%) |

| Men | 11 (38%) | 5 (50%) | 16 (41%) |

| Race | |||

| White/British | 20 (69%) | 9 (90%) | 29 (74%) |

| Asian | 5 (17%) | — | 5 (13%) |

| Other ethnic group | 3 (10%) | — | 3 (8%) |

| Does not wish to state | 1 (3%) | 1 (10%) | 2 (5%) |

| Congenital heart defect | |||

| Ventricular septal defect | 9 (31%) | 3 (30%) | 12 (31%) |

| Atrioventricular septal defect | 2 (7%) | 7 (70%) | 9 (23%) |

| Transposition of great arteries with ventricular septal defect | 5 ⁎ (17%) | — | 5 ⁎ (13%) |

| Secundum atrial septal defect | 3 (10%) | — | 3 (8%) |

| Pulmonary atresia with or without septal defect | 4 (14%) | — | 4 (10%) |

| Aortopulmonary window | 2 (7%) | — | 2 (5%) |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 2 (7%) | — | 2 (5%) |

| Truncus arteriosus | 1 (3%) | — | 1 (3%) |

| Tricuspid atresia | 1 (3%) | — | 1 (3%) |

⁎ Includes 1 patient with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries.

| Medications | Patients Without Down Syndrome (n = 27) | Patients With Down Syndrome (n = 9) | All Patients (n = 36) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amiodarone | 1 (4%) | — | 1 (3%) |

| Digoxin | 4 (15%) | — | 4 (11%) |

| Bisoprolol | 6 (22%) | — | 6 (17%) |

| Candesartan | 1 (4%) | — | 1 (3%) |

| Enalapril | 2 (7%) | — | 2 (6%) |

| Irbesartan | — | 1 (11%) | 1 (3%) |

| Ramipril | 2 (7%) | — | 2 (6%) |

| Sotalol | 1 (4%) | 1 (11%) | 2 (6%) |

| Diltiazem | 1 (4%) | — | 1 (3%) |

| Amiloride | — | 1 (11%) | 1 (3%) |

| Bumetanide | 1 (4%) | 1 (11%) | 2 (6%) |

| Co-amilofruse | 1 (4%) | — | 1 (3%) |

| Eplerenone | 2 (7%) | — | 2 (6%) |

| Furosemide/frusemide | 8 (30%) | 3 (33%) | 11 (31%) |

| Spironolactone | 3 (11%) | 1 (11%) | 4 (11%) |

| Aspirin ⁎ | 10 (37%) | 3 (33%) | 13 (36%) |

| Clopidogrel | 1 (4%) | — | 1 (3%) |

| Warfarin | 15 (56%) | 3 (33%) | 18 (50%) |

| Atorvastatin | 1 (4%) | — | 1 (3%) |

| Simvastatin | 2 (7%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (8%) |

| Ferrous sulfate | 4 (15%) | 2 (22%) | 6 (17%) |

| Sodium feredetate | — | 1 (11%) | 1 (3%) |

| Vitamin B12 injections | 1 (5%) | — | 1 (3%) |

⁎ Two patients received warfarin or clopidogrel concomitantly with aspirin.

Eisenmenger syndrome was present in 35 patients (90%). Underlying congenital cardiac defects and demographics are listed in Table 1 . Four patients had undergone surgical repair or palliations for the defect or its consequences (surgical repair of an atrioventricular septal defect, Mustard procedure in a patient with transposition of the great arteries with ventricular septal defect, Waterston shunt for tricuspid atresia, and stenting for pulmonary arterial stenosis in a patient with previous repair of a ventricular septal defect).

Mean pulmonary arterial pressure in those who underwent cardiac catheterization before bosentan initiation was 72.3 ± 18.6 mm Hg (n = 19), with a mean ratio of pulmonary to systemic pressure of 0.95 ± 0.17 (range 0.48 to 1.33, n = 24).

With the exception of 1 patient with Down syndrome, all patients were successfully titrated to bosentan 125 mg 2 times/day daily after 4 weeks of taking bosentan 62.5 mg 2 times/day. The patient who was initially unable to tolerate the increase in dose was successfully uptitrated to bosentan 125 mg 2 times/day 2 years 8 months after initiation of therapy. Mean durations of bosentan treatment from date of commencement to latest/final 6MWD test or liver function test were 2.1 ± 1.5 years (median 1.7) for all patients (n = 39), 2.2 ± 1.3 years (median 1.8) for patients without Down syndrome (n = 29), and 2.0 ± 2.2 years (median 1.3) for patients with Down syndrome (n = 10).

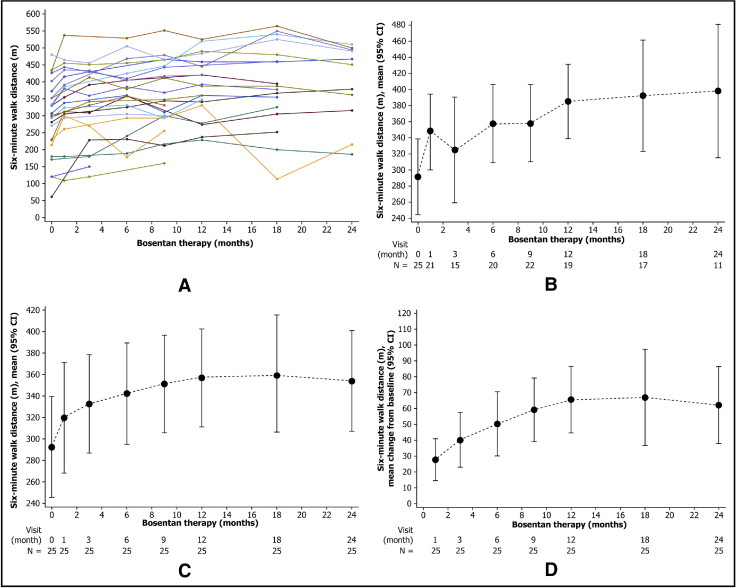

Individual data from patients without Down syndrome (n = 25, 4 patients excluded from analyses because baseline data were not available) showed that 6MWD improved from baseline at almost every time point ( Figure 1 ), with mean improvements from baseline value (293 ± 108 m) achieved at each time point for absolute values, absolute values for LOCF, and change from baseline values for LOCF. The postbaseline average increase in 6MWD of 54 m was highly statistically significant (p <0.0001 vs no increase, random effects model). Male gender was a predictor of 6MWD response to bosentan, with men having a statistically significantly higher average increase in 6MWD of 33 m compared to women (p = 0.016, random effects model). There were no other statistically significant predictors of response among the other covariates tested including age, ethnicity, diagnosis, and baseline oxygen saturation at rest. For patients without Down syndrome, mean pretest oxygen saturation was 84.6 ± 6.0% at baseline (n = 25) and remained stable throughout treatment with bosentan ( Figure 2 ), with no statistically significant change over time (p = 0.24, random effects linear regression model with random intercept). There was no statistically significant relation between change in 6MWD and change in oxygen saturation in this patient group (p = 0.8). Oxygen saturation levels for patients with Down syndrome also remained stable throughout bosentan treatment ( Figure 2 ).