Impaired adherence to medications and health behaviors may mediate the connection between psychiatric symptoms and mortality in cardiac patients. This study assessed the association between improvements in depression/anxiety and self-reported adherence to health behaviors in depressed cardiac patients in the 6 months after cardiac hospitalization. Data were analyzed from depressed patients on inpatient cardiac units who were hospitalized for acute coronary syndrome, heart failure, or arrhythmia and enrolled in a randomized trial of collaborative care depression management (n = 134 in primary analysis). Measurements of depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9), anxiety (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Anxiety subscale), and adherence to secondary prevention behaviors (Medical Outcomes Study-Specific Adherence Scale items) were obtained at baseline, 6 weeks 12 weeks, and 6 months. The association between improvement in depression/anxiety and adherence was assessed by linear regression after accounting for the effects of multiple relevant covariates. At all time points improvement in the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 was significantly and independently associated with self-reported adherence to medications and secondary prevention behaviors. In contrast, improvement in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Anxiety subscale was associated with improved adherence only at 6 weeks. In conclusion, in a cohort of depressed cardiac patients, improvement in depression was consistently and independently associated with superior self-reported adherence to medications and secondary prevention behaviors across a 6-month span, whereas improvement in anxiety was not.

Depression is common in patients with cardiac illness and has been independently associated with poor functional status, recurrent cardiac events, and increased mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), heart failure, and arrhythmias. Although depression may affect cardiac outcomes through direct physiologic mechanisms (e.g., increased inflammation or abnormal platelet function), poor adherence to medication and recommended health behaviors clearly plays a role in this association and may further explain the increased rates of adverse medical events in depressed cardiac patients. Nevertheless, little is known about whether an improvement of mood symptoms is associated with adherence in depressed cardiac patients and even less is known about the connection between anxiety and adherence in these patients. Anxiety has been increasingly identified as a risk factor—possibly independent of depression—for adverse outcomes in cardiac patients. However, few studies have examined the effects of anxiety or anxiety improvement on treatment adherence in patients with acute heart disease or simultaneously assessed the independent effects of anxiety and depression. In this secondary analysis of data from a depression care management trial, we assessed whether improvements in depression and anxiety were independently associated with greater adherence to health behaviors over a 6-month period in a cohort of hospitalized cardiac patients who met criteria for depression during hospitalization.

Methods

This was a secondary analysis from a prospective randomized trial ( http://clinicaltrials.gov , identifier NCT00847132 ) of a 12-week collaborative care depression treatment program versus usual care for depressed patients admitted to inpatient cardiac units. All study procedures were approved by the hospital’s institutional review board.

Eligible patients for the collaborative care study were admitted for ACS, decompensated heart failure, or arrhythmia to inpatient cardiac units at an urban academic medical center from September 2007 through September 2009. These 3 diagnoses were selected because they provide a representative sample of patients in cardiac inpatient units (accounting for approximately 80% of admission diagnoses) and because depression has been associated with poor medical outcomes in patients with each of these conditions. To meet study criteria for clinical depression, patients were required to have a Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) score ≥10 with ≥5 symptoms—including depressed mood or anhedonia—present >1/2 the days for the preceding ≥2 weeks. Patients meeting depression criteria were evaluated further for psychiatric exclusion criteria including bipolar disorder, psychosis, active substance use disorder, cognitive impairment, and active suicidal ideation.

Subjects who met all eligibility criteria and were enrolled were randomized to a 12-week collaborative care intervention (a multipronged intervention using a care manager to provide serial depression assessments and coordinate psychiatrists’ recommendations regarding depression care) or to usual care. Results of the main study have been published elsewhere; briefly, patients receiving the collaborative care intervention had significantly greater decreases in anxiety and depressive symptoms at 6 and 12 weeks (during the intervention) compared to those in usual care. In addition, at 6 months (postintervention) the intervention was associated with greater decreases in the number and intensity of cardiac symptoms and greater self-reported adherence to medication and health behaviors, although its effect on depression waned at this time point.

On enrollment, study staff obtained information about a patient’s sociodemographic characteristics, medical conditions, depression history, and baseline study outcome measurements. Outcome measurements included measures of depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Anxiety subscale [HADS-A]), and health-related quality of life (Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-12 [SF-12] Mental and Physical Component scores). The PHQ-9 was chosen because it is a widely used instrument with high validity and reliability and because it has been used in similar studies of cardiac patients. We used the HADS-A to measure anxiety because it has been used in previous studies of patients with cardiac illness and because it does not contain somatic symptom items that could represent physical symptoms of cardiac illness, unlike such other scales as the Beck Anxiety Inventory or Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7. The SF-12 was used because it is a brief well-validated measurement of health-related quality of life previously used in cardiac patients.

Follow-up assessments by a staff member blinded to group assignment were conducted 6 weeks 12 weeks, and 6 months after enrollment. At all follow-up time points, study measurements (PHQ-9, HADS-A, and SF-12) were repeated. Adherence was also measured during these follow-up assessments using 4 items from the Medical Outcomes Study Specific Adherence Scale (MOS-SAS). These items assessed adherence to a healthy diet, exercise, stress reduction, and medication. For each item, subjects were asked the frequency (from “none of the time” to “all of the time,” scored from 1 to 6) with which they had followed each of these health behaviors in the previous month. We did not measure adherence at baseline because some patients may not have had pre-existing cardiac disease or may not have been prescribed medication before their admission.

We chose to measure self-reported adherence for several reasons. First, other more objective methods of assessing adherence were not appropriate for the present study because measuring adherence using electronic pill caps, dietary logs, multiaxial accelerometers, and other invasive methods is expensive, burdensome, and difficult for this population of patients with complex medical problems. Second, such methods have their own limitations in the accurate measurement of health behavior (e.g., electronic pill caps measure only the number of cap openings and not necessarily the actual pill intake). Third, self-reported adherence has been validated as a reliable predictor of health outcomes. We specifically selected items from the MOS-SAS because of its ease of administration to cardiac patients and because it has been used in multiple previous studies in patients with heart disease including patients who, as in the present study, had been recently hospitalized for an acute cardiac event.

At each time point, all subjects who completed that follow-up assessment were included in the analysis. We initially performed preliminary unadjusted analyses comparing adherence scores between depressed and nondepressed patients (using an established PHQ-9 cutoff score ≥10 ) at our primary time point (6 months) and exploratory time points (6 and 12 weeks) and compared groups using independent-samples t tests.

To determine differences in baseline characteristics between subjects completing follow-up and subjects with missing data at the primary time point (6 months), we compared baseline sociodemographic variables, medical characteristics, and psychiatric symptom measurements using chi-square analysis for dichotomous variables and t tests for continuous variables. We selected 6 months as the primary time point to assess longer-term change, which may be more difficult to sustain and more important in longitudinal prognosis than transient changes in health behaviors.

For the primary analyses, we performed multivariate linear regression using continuous adherence (MOS-SAS) scores at 6 months as the dependent variable. To ensure the most robust analyses, we chose to measure adherence as a continuous variable rather than using a predefined “cutoff” for adherence. To avoid overfitting and to use a rational model creation, we also selected independent variables a priori based on previous literature rather than preselecting variables with favorable bivariate comparisons and limited the number of variables in the model.

Independent variables selected for the model included age, gender, admission diagnosis, living alone (social support and living status have been linked to adherence in patients with heart disease ), baseline functional status as measured by the SF-12 Physical Component Scale (this scale/domain has been linked to treatment adherence), smoking status at admission (smoking has been linked to health behavior adherence and itself is a target behavior ), employment (a predictor of poor treatment adherence in cardiac patients), diabetes mellitus (linked to poor adherence), change in depression score from baseline (PHQ-9), and change from baseline anxiety score (HADS-A).

We also performed exploratory supplemental analyses to identify factors associated with combined and medication adherence at 6 and 12 weeks after hospitalization. These analyses used multivariate linear regression in the same manner as the 6-month assessments. All analyses were performed using STATA 11.0 (STATA Corp., College Station, Texas). Because the predetermined primary analysis was for 6 months (a single time point) p values were 2-tailed with significance set at ≤0.05. If we had used a Bonferroni correction to account for the 3 time-point analyses, a p value of 0.0167 would have been needed to achieve significance.

Results

One hundred seventy-five participants enrolled in the trial; 14 subjects (8.0%) died during the 6-month study period. Of the 161 surviving patients, 134 (83.2%) completed all portions of the 6-month follow-up evaluation and were included in the primary analysis. Of these 134 subjects, 70 (52.2%) were randomized to the collaborative care intervention and 64 (47.8%) to usual care. Baseline characteristics of these 134 subjects are listed in Table 1 . There were no significant differences on any baseline sociodemographic, medical, medication-related, or psychiatric measurement between those who did and those who did not compete the 6-month follow-up, with 1 exception: patients who completed follow-up were more likely to be younger than patients who did not complete follow-up (61.5 vs 65.1 years, t = 1.64, p = 0.05). Regarding supplementary time points, 124 patients completed 6-week follow-up assessments and 134 completed the 12-week follow-up. Initial mean PHQ-9 score at enrollment was 17.8 (SE 0.33). Rates of depression response (50% decrease in PHQ-9 score from baseline) at each time point were 52.8% at 6 weeks, 58.5% at 12 weeks, and 54.7% at 6 months.

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 61.49 ± 11.8 |

| Men | 64 (48%) |

| Married | 55 (41%) |

| Employed | 36 (27%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 43 (32%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia ⁎ | 76 (57%) |

| Hypertension ⁎ | 78 (58%) |

| Current smoking | 26 (19%) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 39 (29%) |

| Admission diagnosis | |

| Heart failure | 44 (33%) |

| Unstable angina | 38 (28%) |

| Myocardial infarction | 23 (17%) |

| Arrhythmia | 29 (22%) |

| Previous depression | 96 (72%) |

| Duration of current depression >1 month | 106 (79%) |

| Prescribed antidepressant at admission | 59 (44%) |

| Medications prescribed at discharge | |

| Aspirin | 100 (75%) |

| β-Adrenergic blocker | 106 (79%) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor | 68 (51%) |

| Statin | 97 (72%) |

| Diuretic | 70 (52%) |

| Antidepressant | 98 (73%) |

| Baseline outcome variables, mean ± SD | |

| Depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score) | 17.8 ± 3.6 |

| Anxiety (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Anxiety subscale) | 10.5 ± 4.1 |

| Physical health-related quality of life (Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-12 Physical Component score) | 32.0 ± 9.8 |

| Length of hospital stay (days), mean ± SD | 7.2 ± 7.8 |

⁎ Hypertension and hypercholesterolemia diagnoses were determined by medical record review.

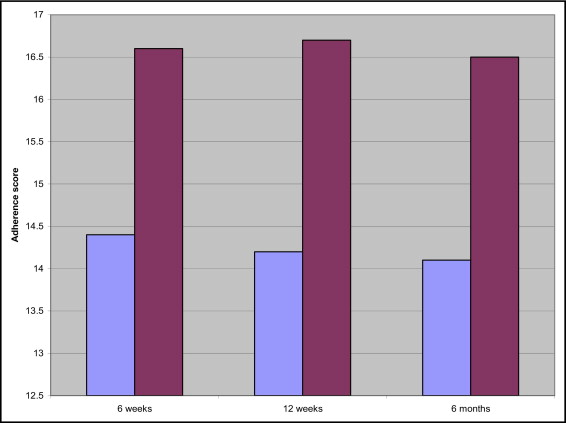

At 6 months, patients with PHQ-9 scores signaling depression (PHQ-9 ≥10, n = 63) had significantly lower MOS-SAS adherence scores than nondepressed patients (PHQ-9 <10, n = 71, adherence score 14.1 vs 16.5 in depressed vs nondepressed patients, t = 3.98, p <0.001). Results were similar at 6 weeks (14.4 in depressed vs 16.6 in nondepressed patients, t = 4.19, p <0.001) and 12 weeks (14.2 vs 16.7, t = 4.08, p <0.001; Figure 1 ) .

Multivariate linear regression at the primary time point (6 months) revealed a strong and significant relation between change in PHQ-9 score and adherence at 6 months (beta 0.263, p <0.001) independent of all covariates ( Table 2 ). A change in HADS-A score and other covariates were not associated with 6-month adherence measured by the MOS-SAS.

| Variable | Coefficient | SE | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9) from baseline | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.15–0.37 | <0.001 |

| Change in anxiety (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Anxiety subscale) from baseline | −0.02 | 0.07 | −0.15 to 0.11 | 0.75 |

| Age | −0.39 | 0.02 | −0.09 to 0.01 | 0.14 |

| Gender | 0.42 | 0.57 | −0.72 to 1.56 | 0.47 |

| Employment status | 1.04 | 0.69 | −0.34 to 2.42 | 0.14 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.08 | 0.61 | −1.13 to 1.29 | 0.89 |

| Admission diagnosis | 0.24 | 0.36 | −0.47 to 0.96 | 0.51 |

| Physical health-related quality of life (initial Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-12 Physical Component Scale score) | −0.007 | 0.03 | −0.06 to 0.05 | 0.82 |

| Current smoker | −0.99 | 0.75 | −2.48 to 0.49 | 0.19 |

| Living alone | −0.56 | 0.66 | −1.85 to 0.74 | 0.39 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree