Diseases of the Aorta

The aorta can harbor many different lesions, from a benign aneurysm to a life-threatening dissection, that echocardiography can help identify. Major conditions that affect the aorta are atherosclerosis and hypertension, but other conditions, including genetic (Marfan syndrome or bicuspid aortic valve), infectious (syphilitic or mycotic aneurysm), traumatic, or inflammatory (vasculitis or arteritis), can produce characteristic abnormalities. From multiple transthoracic (TTE) and transesophageal (TEE) echocardiographic imaging windows, the entire thoracic and proximal abdominal aorta can be visualized. The ascending aorta is visualized best from the parasternal long-axis view on TTE and from a 120-degree to 140-degree multiplane TEE view (1). The aortic arch and proximal portion of the descending thoracic aorta are seen well on a suprasternal notch examination (see Chapter 2). Scanning of the abdominal aorta from the subcostal view should be a routine part of a TTE examination (2). Diseases involving the aorta include aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, sinus of Valsalva aneurysm with or without rupture into the surrounding cardiac chambers (most commonly the right-heart chambers), aortic ulcer intramural hematoma, aortic rupture, atheromatous debris, aortic abscess, and coarctation of the aorta.

Aortic Aneurysm

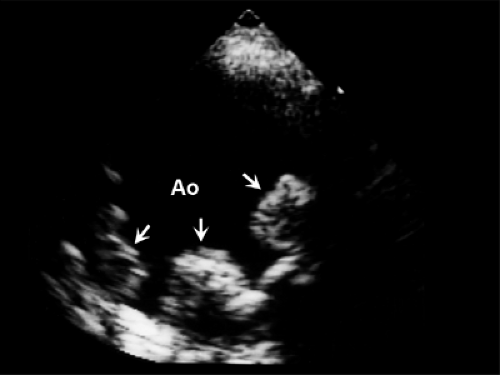

Aortic aneurysm is a relatively common finding in the elderly population because of aging, hypertension, or atherosclerosis. It also is found in patients who have aortic valve disease, Marfan syndrome, or annuloectasia. Aortic dilatation is detected easily with TTE and TEE. When the aneurysm reaches a diameter of 5.5 to 6 cm, the incidence of rupture increases. Smaller aneurysms require serial follow-up studies in which the dimensions of the aorta are measured at specific locations. Patients with Marfan syndrome have a high prevalence of cardiovascular abnormalities, including aortic dilatation and mitral valve prolapse (3,4) (Fig. 19-1). In a study of 40 patients with Marfan syndrome, 78% had aortic root dilatation and 65% had mitral valve prolapse. In follow-up examinations, the mean rate of aortic root dilatation was 1.9 mm per year. Aortic dissection is the most serious complication of Marfan syndrome, and prophylactic therapy with β-blockers appears to be effective in slowing the rate of aortic dilatation and reducing the development of aortic complications. In patients with a high risk of dissection (family history or rapid increase in aorta size), surgery may be recommended even before the dimension the aorta reaches 5 cm (5). After surgery on the aorta, continuous surveillance for other complications of the aorta in patients with Marfan syndrome is important because notable aortic regurgitation or dissection of the distal aorta can develop. An abdominal aneurysm may be difficult to detect on clinical examination. A routine subcostal view during TTE identifies clinically unsuspected abdominal aneurysms (see Fig. 2-14), especially if a patient is older than 70 years and has hypertension (2).

Aneurysm of the Sinus of Valsalva

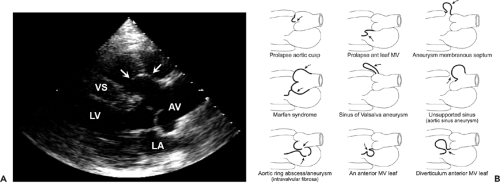

Absence of the media of the sinus aortic wall results in aneurysmal dilatation of the sinus of Valsalva, first described by Morrow and colleagues in 1957 (6). A sinus of Valsalva aneurysm may not create symptoms and can be an incidental finding, but it can compress adjacent structures or rupture into the adjacent cardiac chambers (most commonly, the right atrium or right ventricle) or into the ventricular septum (7,8). Parasternal long-axis and short-axis views should be able to demonstrate this aneurysm and associated structural abnormalities (Fig. 19-2). The apical view is helpful in differentiating this from an aneurysm of a membranous ventricular septum

(Fig. 19-2). There are several other morphologically distinct aneurysms within the region of the left ventricular outflow tract. Morphologic features of various aneurysms are shown schematically in Figure 19.2 B. These aneurysms can be distinguished confidently with comprehensive TTE and TEE examinations (7,8). The natural history of sinus of Valsalva aneurysms is not well known, but they have been associated with an increased incidence of endocarditis, fatal rupture, and rare embolic events as well as a fistulous communication with a cardiac chamber. Surgical repair is usually recommended once the aneurysm has been diagnosed, even in asymptomatic patients (7,9).

(Fig. 19-2). There are several other morphologically distinct aneurysms within the region of the left ventricular outflow tract. Morphologic features of various aneurysms are shown schematically in Figure 19.2 B. These aneurysms can be distinguished confidently with comprehensive TTE and TEE examinations (7,8). The natural history of sinus of Valsalva aneurysms is not well known, but they have been associated with an increased incidence of endocarditis, fatal rupture, and rare embolic events as well as a fistulous communication with a cardiac chamber. Surgical repair is usually recommended once the aneurysm has been diagnosed, even in asymptomatic patients (7,9).

Atherosclerosis and Aortic Debris

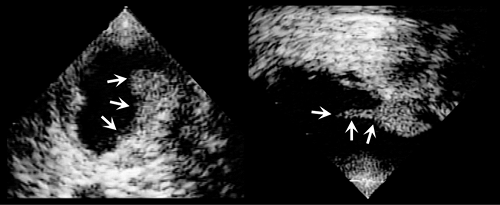

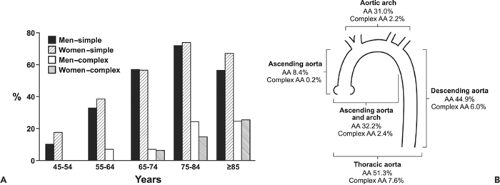

Because imaging of the aorta is a routine part of TEE examinations, atherosclerotic plaques and debris are common findings in elderly patients. TEE was performed in an asymptomatic Olmsted County, Minnesota, population (10,11) as part of the SPARC (Stroke Prevention Assessment of Risk in a Community) study. The frequency of simple and complex aortic atherosclerosis within each SPARC age and sex group and the distribution of atherosclerosis are shown in Figure 19-3. Unlike intramural hematoma, aortic plaques usually are irregularly shaped and frequently mobile (Fig. 19-4). The incidence of aortic debris is higher among patients who have had an embolic event (12,13). The prevalence of ulcerated plaques in the aortic arch was studied by Amarenco and colleagues (13) in patients who had a stroke. Ulcerated plaques were present in 26% of 239 patients who had a cerebrovascular accident but in only 5% of the 261 patients without neurologic disease. Subsequently, the French stroke study determined that atheromatous plaques 4 mm or more thick are more likely to cause

an embolic event (14). Although preliminary data suggest that chronic anticoagulation with warfarin may be beneficial in decreasing embolic events in patients with atheromatous plaque, surgical removal is indicated if embolism recurs during anticoagulation (15). An aortic plaque can be hemodynamically compromising or flow-limiting and result in acquired coarctation of the aorta or ischemia of the lower extremity (or both), especially in patients with low cardiac output (Fig. 19-5). Atherosclerosis of the ascending aorta was found to be an independent predictor of long-term neurologic events and mortality (16). In the SPARC study performed in Olmsted County, age, smoking history, and systolic blood pressure were independently associated with aortic atherosclerosis (11).

an embolic event (14). Although preliminary data suggest that chronic anticoagulation with warfarin may be beneficial in decreasing embolic events in patients with atheromatous plaque, surgical removal is indicated if embolism recurs during anticoagulation (15). An aortic plaque can be hemodynamically compromising or flow-limiting and result in acquired coarctation of the aorta or ischemia of the lower extremity (or both), especially in patients with low cardiac output (Fig. 19-5). Atherosclerosis of the ascending aorta was found to be an independent predictor of long-term neurologic events and mortality (16). In the SPARC study performed in Olmsted County, age, smoking history, and systolic blood pressure were independently associated with aortic atherosclerosis (11).

Figure 19-2 A: Parasternal long-axis view of a transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrating aneurysm (arrows) of the sinus of Valsalva. AV, aortic valve; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; VS, ventricular septum. B: Drawings of various aneurysms found in the region of the left ventricular outflow tract. an, aneurysm; ant, anterior; MV, mitral valve. (From Meier et al [8]. Used with permission.) |

Figure 19-3 A: Frequency of simple and complex aortic atherosclerosis by age group and sex. B: Distribution of atherosclerosis in the thoracic aorta. Both simple aortic sclerosis and complex aortic sclerosis are most common in the descending thoracic aorta. (From Agmon et al [10]. Used with permission.) |

Aortic Dissection and Intramural Hematoma

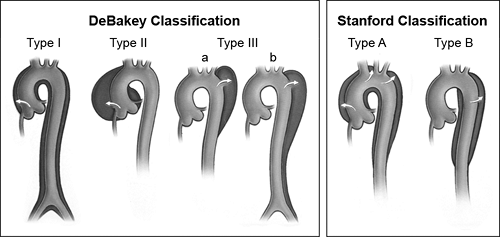

Aortic dissection is a potentially life-threatening condition that requires prompt diagnosis and treatment. The location of the aortic dissection dictates the treatment modality. The classification of aortic dissections according to the location of the tear and the extent of involvement is shown in Figure 19-6 (17). A proximal aortic dissection (DeBakey types I and II or Stanford type A) requires immediate surgical repair, whereas a distal dissection (DeBakey type III or Stanford type B) is usually managed medically unless there is persistent pain or a clinically significant compromise to vital organs. Therefore, both

diagnosis and identification of the location and extent of an aortic dissection are important for optimal management.

diagnosis and identification of the location and extent of an aortic dissection are important for optimal management.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|