Echocardiography is the preferred initial imaging method for assessment of cardiac masses. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging, with its excellent tissue characterization and wide field of view, may provide additional unique information. We evaluated the predictive value of echocardiography and CMR imaging parameters to identify tumors and malignancy and to provide histopathologic diagnosis of cardiac masses. Fifty patients who underwent CMR evaluation of a cardiac mass with subsequent histopathologic diagnosis were identified. Echocardiography was available in 44 of 50 cases (88%). Echocardiographic and CMR characteristics were evaluated for predictive value in distinguishing tumor versus nontumor and malignant versus nonmalignant lesions using histopathology as the gold standard. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the 2 imaging methods’ ability to provide the correct histopathologic diagnosis. Parameters associated with tumor included location outside the right atrium, T2 hyperintensity, and contrast enhancement. Parameters associated with malignancy included location outside the cardiac chambers, nonmobility, pericardial effusion, myocardial invasion, and contrast enhancement. CMR identified 6 masses missed on transthoracic echocardiography (4 of which were outside the heart) and provided significantly more correct histopathologic diagnoses compared to echocardiography (77% vs 43%, p <0.0001). In conclusion, CMR offers the advantage of identifying paracardiac masses and providing crucial information on histopathology of cardiac masses.

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the predictive value of echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging parameters to identify cardiac tumors and malignant masses ( Table 1 ), as well as to diagnose the histopathology for cardiac masses using histologic confirmation as the gold standard. We hypothesized that CMR provides incremental diagnostic value to echocardiography.

| Benign tumors and tumor-like lesions |

| Rhabdomyoma |

| Histiocytoid cardiomyopathy |

| Hamartoma of mature cardiac myocytes |

| Adult cellular rhadomyoma |

| Cardiac myxoma |

| Papillary fibroelastoma |

| Haemangioma, NOS |

| Capillary Haemangioma |

| Cavernous Haemangioma |

| Cardiac fibroma |

| Lipoma |

| Cystic tumor of the atrioventricular node |

| Granular cell tumor |

| Schwannoma |

| Tumors of uncertain behavior |

| Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor |

| Paraganglioma |

| Germ cell tumors |

| Teratoma, mature |

| Teratoma, immature |

| Yolk sac tumor |

| Malignant Tumors |

| Angiosarcoma |

| Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma |

| Osteosarcoma |

| Myxofibrosarcoma |

| Leiomyosarcoma |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Synovial sarcoma |

| Miscellaneous sarcomas |

| Cardiac lymphomas |

| Metastatic tumors |

| Tumors of the pericardium |

| Solitary fibrous tumor, malignant and nonmalignant |

| Angiosarcoma |

| Synovial sarcoma |

| Malignant mesothelioma |

| Germ cell tumors |

| Teratoma, mature and immature |

| Mixed germ cell tumor |

Methods

Our study was approved by the institution review board at our medical center in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

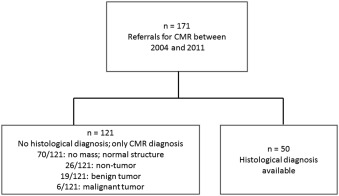

We retrospectively identified 171 patients (58% men, age 55 ± 19 years) referred for CMR evaluation of cardiac/paracardiac mass from October 2004 to February 2011. Of these 171 patients, 121 patients were managed conservatively ( Figure 1 ). Six malignant masses were managed conservatively because of poor surgical candidacy, unresectability, and patient preference. Tissue for histopathology was obtained in 50 patients through either percutaneous (n = 7) or surgical (n = 43) approaches after CMR study; 44 had echocardiograms.

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was performed using commercially available equipment (iE33, Sono 7500; Philips Healthcare, Andover, Massachusetts). Images were obtained in standard views. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) was also performed using commercially available equipment and standard imaging planes. Contrast agents were not used. Echocardiography studies were clinically interpreted by level 3-trained cardiologists at our institution. TTE was performed in 38 of 44 cases, TEE alone in 6 of 44 cases, and both TTE and TEE in 11 of 44. The reports were reviewed for imaging parameters (see statistical analysis). If a mass was missed on TTE and seen on TEE (as in 1 case), TEE served as the reference point.

CMR studies were performed on a 1.5-T (Avanto or Sonata) or 3.0-T (TimTrio or Verio) MR system (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) using a torso and spine coil in conjunction with electrocardiographic gating. Imaging was performed with standard cardiac mass evaluation protocol consisting of the following sequences in all patients: (1) scout images to identify cardiac axes, (2) black-blood double inversion recovery imaging of the thorax in axial and sagittal planes, (3) cine 2-dimensional steady-state free precession (SSFP) imaging in stacked horizontal long axis (4-chamber) and short-axis planes to cover the entire heart, (4) T1-weighted and T2-weighted fast turbo spin echo and short tau inversion recovery sequences, (5) dynamic first-pass perfusion after an intravenous injection of 0.15 mmol/kg gadolinium-DTPA, (6) precontrast and postcontrast 3-dimensional volumetric interpolated breath-hold sequence performed in the axial planes, and (7) postcontrast T1-weighted fast turbo spin echo and inversion recovery late gadolinium enhancement imaging (5 to 10 minutes after contrast). CMR studies were clinically interpreted by 1 of 3 level 3 CMR-trained physicians at our institution. The finalized CMR reports were reviewed for information on characteristics of the mass.

Continuous data are reported as mean ± SD, and categorical data are expressed as frequency or percentage. Individual morphologic features (location, size, number, mobility, myocardial infiltration, and presence of pericardial or pleural effusion) and imaging characteristics (homogenous/heterogeneous, signal intensity on T1/T2-weighted sequences, and contrast enhancement on first-pass enhancement and late gadolinium enhancement) were evaluated as potentially useful imaging measures for mass diagnosis using binary logistic regression analysis. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the number of times a correct histologic diagnosis was provided by each imaging study using pathology as the reference standard. All statistical tests were conducted at the 2-sided 5% significance level using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Fifty patients (50% men, mean age 46 ± 17 years) had histologic diagnosis of their cardiac mass ( Table 2 ). Pathologically confirmed malignant tumors occurred at almost the same frequency in men and women (11 of 25, 44% men vs 10 of 25, 40% women). A total of 10 of 50 patients had a preexisting cancer diagnosis. Of those, 6 of 10 had recurrence of disease on pathology, 2 of 10 had a new primary cancer diagnosis, and 2 of 10 were diagnosed with a thrombus. Location of tumors is listed in Table 3 .

| All Patients ( n=50 ) | Men ( n=25 ) | Women ( n=25 ) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 46±17 | 46±17 | 46±17 |

| Previous Cancer History | 10 | 4 | 6 |

| History of Atrial Fibrillation | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| History of CVA ∗ | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Non-tumor | 15 | 8 | 7 |

| Thrombus | 9 | 4 | 5 |

| Mitral valve with myxoid degeneration | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Pericardial cyst | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Non-neoplastic liver | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Thymic cyst | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Intramyocardial cyst | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Benign Tumor | 14 | 6 | 8 |

| Myxoma | 9 | 5 | 4 |

| Papillary fibroelastoma | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Lipoma | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Lipoleiomyoma | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Malignant Tumor | 21 | 11 | 10 |

| Teratoma | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Paraganglioma | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Thymoma | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Non-small cell adenocarcinoma | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Metastatic breast cancer | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Metastatic clear cell renal cancer | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Poorly differentiated sarcoma | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Osteosarcoma | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Fibrosarcoma | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Liposarcoma | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Desmoplastic sarcoma | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Angiosarcoma | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Location | Non-Tumor | Benign Tumor | Malignant Tumor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right Atrium | 8 | 3 | 5 |

| Right Ventricle | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Left Atrium | 2 | 8 | 0 |

| Left Ventricle | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Pericardium | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Epicardial | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Extracardiac | 3 | 1 | 8 |

In 44 cases (88% of cohort) with echocardiography, CMR was performed after echocardiography at mean interval of 13 ± 34 days. CMR identified a mass lesion in all cases that underwent intervention for histologic diagnosis. CMR was performed 20 ± 34 days before intervention.

In 5 of 44 cases (11%), TTE (TEE not performed) did not identify a mass that was later seen on CMR and pathology. All 5 masses were >3 cm on CMR. Of the missed masses, 2 were in the anterior mediastinum, 2 in the pericardium ( Figure 2 ), and 1 in the left atrium. There was an additional paracardiac mass located in the middle mediastinum that was initially visualized on left heart catheterization, missed on TTE but visualized on TEE.

Table 4 demonstrates individual age-adjusted and gender-adjusted echocardiography and CMR parameters associated with tumor and malignancy.

| Echocardiography Parameters | Unadjusted | Adjusted for Age and Gender | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor (P -value) | Malignancy (P -value) | Tumor (P -value) | Malignancy (P- value) | |

| Location outside the right atrium | 0.0063 ∗ | 0.4037 | 0.0049 ∗ | 0.4661 |

| Location outside the atria and ventricles | 0.0405 ∗ | 0.0054 ∗ | 0.0444 ∗ | 0.0044 ∗ |

| Size > 1 cm | 0.1351 | 0.9470 | 0.1224 | 0.9137 |

| Non-Mobility | 0.5994 | 0.0031 ∗ | 0.5084 | 0.0039 ∗ |

| Number of Masses | 0.5165 | 0.3371 | 0.5181 | 0.4324 |

| Myocardial Invasion | 0.2300 | 0.1470 | 0.3543 | 0.2233 |

| Pericardial Effusion | 0.6863 | 0.0049 ∗ | 0.4578 | 0.0088 ∗ |

| Pleural Effusion | 1.0000 | 0.3864 | 0.9999 | 0.3798 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree