Everolimus-Eluting Stents (Xience V™/Promus™)

In the EES (manufactured by Abbott Vascular (Santa Clara, CA) and distributed as the Xience V and now Xience PRIME stents, and also originally distributed by Boston Scientific as the Promus stent), everolimus (100 µg/cm

2) is released from a thin (7.8 µm), nonadhesive, durable, biocompatible, fluorocopolymer consisting of vinylidene fluoride and hexafluoropropylene monomers, coated onto a low-profile (81 µm strut thickness), flexible, cobalt chromium stent. (The original Xience V base stent platform has been updated in the Xience PRIME stent to the Multi-link 8 BMS platform, a more deliverable version of the Vision platform). The release kinetics of EES are similar to that seen with sirolimus from the SES (˜80% of the drug released at 30 days, with none detectable after 120 days). The polymer is elastomeric, and experiences minimal bonding, webbing, or tearing upon expansion. Fluoropolymers have additionally been shown to resist platelet and thrombus deposition in blood-contact applications.

21,

76,

77 The EES polymer has also been demonstrated to be nonin-flammatory in porcine experiments. Preclinical studies have demonstrated more rapid coverage of the stent struts with functional endothelialization with EES compared to SES, PES, or ZES.

53In the small SPIRIT First trial, the EES was shown to markedly reduce the extent of angiographic late loss at 6 and 12 months compared to the otherwise identical cobalt chromium Vision BMS.

78 Subsequently, the EES has been studied in multiple randomized trials comparing this device to PES (the predominant comparator), SES, ZES, and BMS (

Table 31.3).

42,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89 The large SPIRIT IV trial,

42 enrolling 3,687 patients with stable coronary artery disease undergoing PCI of up to three lesions in three vessels, was a pivotal FDA approval study of the EES, randomizing patients to EES versus PES(E). While this study had broader inclusion criteria than first-generation DES approval studies, patients with unstable acute coronary syndromes, MI, thrombus, chronic occlusions, vein graft lesions, and true bifurcation lesions were excluded. The primary endpoint of TLF (a composite of cardiac death, target-vessel MI, or ischemia-driven TLR) was significantly lower at 1 year with EES compared to PES (3.9% versus 6.6%,

P = 0.0008). Rates of stent thrombosis (0.3% versus 1.1%,

P = 0.003), MI (1.9% versus 3.1%,

P = 0.02), and TLR (2.3% versus 4.5%,

P = 0.0008) were also lower with EES compared to PES. Longer-term follow-up of SPIRIT IV to 3 years

85 has demonstrated sustained reductions in TLF, MI, and stent thrombosis with EES over PES (0.8% versus 1.9%), but narrowing of the initially observed difference in TLR with each stent (6.2% versus 7.8%,

P = 0.06). However, both all-cause mortality (3.2% versus 5.1%,

P = 0.02) and death or MI (5.9% versus 9.1%,

P = 0.001) were reduced with EES compared to PES. These data from SPIRIT IV parallel results from the unrestricted “all-comer” COMPARE trial, in which 1,800 patients were randomized to EES versus PES(L). The primary endpoint of MACE at 1 year (death, MI, or TVR) was lower with EES compared to PES (6.2% versus 9.1%,

P = 0.02), driven by reductions in stent thrombosis (0.7% versus 2.6%,

P = 0.002), MI (2.8% versus 5.4%,

P = 0.007), and TLR (1.7% versus 4.8%,

P = 0.0002). Notably, between 1 and 3 years in this high-risk study cohort (in which only ˜15% of patients were maintained on dual antiplatelet therapy), fewer stent thrombosis, MI, and TLR events occurred with EES compared to PES.

80In contrast to the marked differences observed between EES and PES, smaller differences have been observed between EES and SES in several randomized trials. In the SORT OUT IV trial,

87 2,774 unselected patients were randomized to EES versus SES and followed through the Danish Civil Registration System. Similar 9-month outcomes were observed between EES- and SES-treated patients although definite stent thrombosis occurred in fewer EES- than SES-treated patients at both 9 and 18 months (18 months: 0.2% versus 0.9%). In the 2,314-patient BASKET-PROVE multicenter trial comparing EES, SES, and BMS (the otherwise identical cobalt chromium Vision BMS) in large coronary arteries requiring >3.0 mm stents,

93 EES, SES, and BMS were associated with similar rates of cardiac death or nonfatal MI at 2 years and the rate of TVR was similar between EES and SES. However, the rate of TVR was significantly lower with both EES and SES compared to BMS (3.1% for EES, 3.7% for SES, 8.9% for BMS), even in larger arteries with low rates of restenosis. The majority of comparative trials between EES and SES have demonstrated largely similar angiographic outcomes with EES and SES

89,

94,

96 except for the ESSENCE-DIABETES trial,

88 in which EES was associated with lower rates of angiographic late loss and binary restenosis in diabetic patients at 8 months compared to SES. Excepting this trial’s results, whether clinically apparent efficacy differences between EES and SES are manifest in the highest-risk patient and lesion subsets remains unknown.

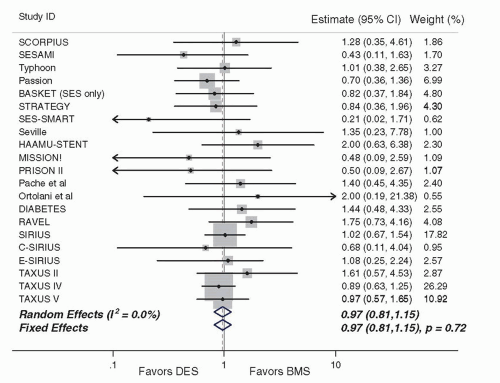

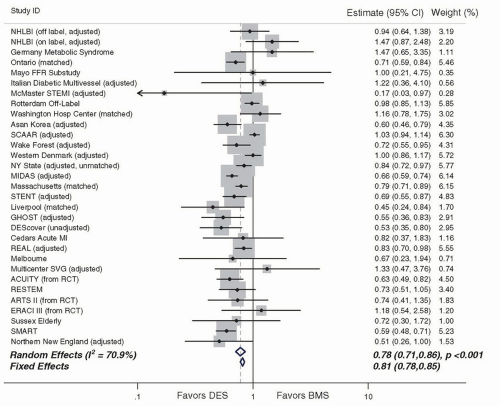

One intriguing attribute of EES that has emerged is the low rate of stent thrombosis observed with this stent. First demonstrated in SPIRIT IV and COMPARE, these findings have also been validated in several other studies, summarized in a metaanalysis of 13 randomized EES trials (

N = 17,101) that demonstrated lower rates of ST with EES compared to non-EES DES.

100 These data, combined with further observational validation of these findings,

101 support the use of the second-generation EES over previously existing first-generation DES with respect to a safety advantage (in addition to efficacy). Further, whether EES can achieve lower or noninferior overall rates of stent thrombosis compared to BMS is an area of active interest, piqued by both preclinical data as well as studies such as the randomized EXAMINATION trial of 1,504 patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI),

95 in which the rate of definite/probable stent thrombosis at 1 year was significantly lower in EES-treated patients compared to those treated with BMS (0.9% versus 2.6%;

P = 0.01). Similarly, in a large network metaanalysis of head-to-head DES trials (49 trials,

N = 50,844), the use of EES was associated with statistically significant reductions in 1- and 2-year stent thrombosis compared to other DES, as well as BMS.

102 Whether EES can definitely reduce stent thrombosis compared to BMS is being actively tested in the randomized controlled HORIZONS-II trial.

Another iteration of EES has involved the use of everolimus eluted by the same stable fluropolymer as in the original EES, but on a platinum chromium stent platform (Promus Element, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA). This stent was evaluated in the randomized PLATINUM trial,

99 which randomized 1,530 patients undergoing PCI of one or two de novo native lesions to treatment with the standard EES versus the Promus Element stent. The rates of efficacy and safety outcomes were very similar with both stents in this trial, which ultimately led to FDA approval of this EES platform.

In summary, in a broad cross-section of patients undergoing PCI, EES have shown significant improvements in safety and efficacy outcomes over first-generation DES. The finding of lower rates of stent thrombosis with EES, particularly compared to predecessor DES systems and in some cases even compared to BMS is notable, and suggests that this stent may have set a new standard for DES safety, if these findings can be further validated in larger adequately powered clinical trials.

Zotarolimus-Eluting Stents

Endeavor

Although studied contemporaneously with first-generation SES and PES, the zotarolimus-eluting Endeavor stent (ZES(E), Medtronic, Santa Rosa, CA) was originally conceived as a “second-generation DES,” rapidly eluting zotarolimus (10 µg per 1 mm stent length) from a thin layer (5.3 µm) of the biocompatible polymer phosphorylcholine from a flexible, low-profile (91 µm strut thickness) cobalt chromium stent. Phosphorylcholine is a naturally occurring phospholipid found in the membrane of red blood cells, and is resistant to platelet adhesion.

103 The potencies of zotarolimus, everolimus, and sirolimus are roughly comparable, and zotarolimus is somewhat more lipophilic. However, the release rate of zotarolimus from Endeavor (˜90% within 7 days, 100% within 30 days) is significantly faster than everolimus and sirolimus are released from EES and SES stents respectively.

In the Endeavor I FIM study,

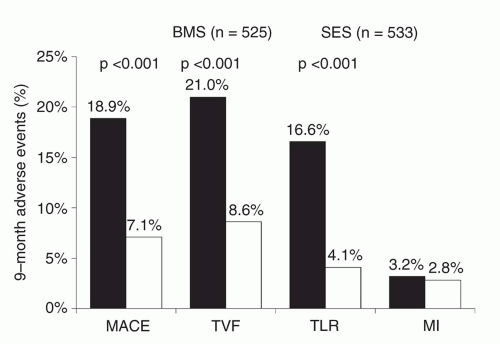

104 ZES(E) was demonstrated to have a low rate of TLR (1%), despite a mean in-stent late lumen loss of 0.61 mm at 12 months. The ZES(E) was subsequently compared to its base BMS in the ENDEAVOR II randomized trial,

105,

106 conducted in 1,197 patients with noncomplex lesions. In this trial, ZES(E) was associated with lower rates of TVF and TLR at 9 months compared to BMS; these results were sustained at follow-up up to 5 years. Once again, 9-month angiographic in-stent late loss (at 0.61 mm) in this trial was greater than previously seen with either SES or PES, but compared to BMS, in-segment binary restenosis was reduced from 35.0% to 13.2% (

P < 0.0001).

A series of head-to-head DES studies in the ENDEAVOR clinical trial program was launched with a 436-patient angiographic trial, ENDEAVOR III, which was designed to demonstrate noninferiority of ZES(E) to the Cypher SES. In this trial, the amounts of late loss and rate of restenosis at angiographic follow-up were significantly greater with ZES(E) compared to SES.

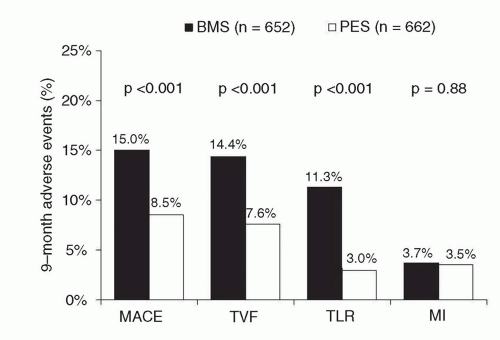

107 Despite these findings, the overall rates of clinical restenosis endpoints were not dissimilar between treatment arms in this trial, and as such, the larger ENDEAVOR IV trial (

N = 1,548) was conducted with a primary clinical endpoint (rather than an angiographic one). In this trial, which randomized patients with noncomplex coronary lesions to treatment with ZES(E) versus PES, despite greater late loss and angiographic restenosis with ZES(E) compared to PES, ZES(E) had noninferior 9-month rates of TVF and comparable 12-month rates of TLR.

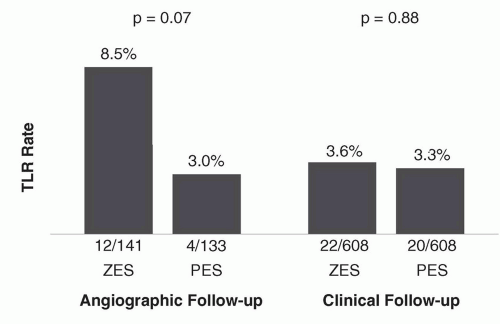

41 Rates of TLR were lowest and in fact indistinguishable between both stents particularly among patients who were assigned to receive clinical follow-up alone (rather than routine angiographic follow-up) (

Figure 31.9), emphasizing a somewhat “artificial” clinical trial phenomenon previously described as the “oculostenotic reflex”.

108 The ENDEAVOR IV findings ultimately led to device approval of ZES(E) in the United States. The 5-year follow-up of this trial has been recently presented,

109 demonstrating comparable rates of TLR for ZES(E) compared with PES (7.7% versus 8.6%;

P = 0.70). More notably, the ZES(E) demonstrated a superior late safety profile with lower very late stent thrombosis (0.4% versus 1.8%;

P = 0.012) and a lower overall incidence of cardiac death or MI (6.4% versus 9.1%;

P = 0.048) compared to PES at 5 years.

Several trials have compared ZES(E) to other DES in unrestricted patient populations. In the SORT OUT III trial,

110 a trial notable for a design that employed follow-up through a nationwide clinical registry in Denmark, 2,333 patients

(nearly 50% of whom presented with acute coronary syndromes) were randomized to ZES(E) versus SES. In this trial, treatment with ZES(E) was associated with higher rates of 9-month major adverse cardiac events (MACE: cardiac death, MI, or TVR: 6% versus 3%,

P =

0.0002), as well as endpoints of MI, stent thrombosis, and TLR, differences which persisted at 18 months (with the exception of stent thrombosis). The ISAR-TEST-2 trial was a three-way 1:1:1 randomized trial in 1,007 patients of an investigational combination sirolimus/probucol-eluting stent versus ZES(E) versus SES.

111,

112 Compared to SES, ZES(E) resulted in higher rates of late loss, angiographic restenosis (the primary endpoint), and TLR at 6 to 8 months, with similar rates of death, MI, and stent thrombosis. A larger study, the ZEST trial, randomized 2,645 patients with simple and complex coronary artery disease to ZES(E), SES, or PES.

113,

114 In this trial, while SES demonstrated the lowest degree of late loss and binary restenosis, ZES(E) was intermediate between SES and PES with respect to rates of MACE, TVR, and TLR. There were no significant differences in the 2-year rates of death, MI, or stent thrombosis between the two stents.

Overall, both the pivotal approval trials within the ENDEAVOR clinical program as well as the investigator-initiated clinical trials of ZES(E) demonstrate lesser neointimal suppression with this stent compared to either SES or PES, resulting in lesser performance of this stent with respect to angiographically measured trial endpoints. However, ZES(E) is clearly superior in efficacy to BMS, and likely comparable to other stent platforms in reducing clinical restenosis in less complex lesions, particularly in the absence of routine angiographic follow-up. The findings of very low rates of late adverse safety events including very late stent thrombosis as well as cardiac death or MI

115 with ZES(E) is a notable positive attribute of this stent, particularly in light of the potential ongoing thrombotic risks of SES and PES.

116 In this regard the large, randomized PROTECT trial has completed enrollment of 8,800 patients to ZES(E) versus SES, and is the first clinical DES study powered to demonstrate a difference in stent thrombosis between two stent platforms (with ascertainment of the primary endpoint at 3 years).

Resolute

The Resolute stent (Medtronic Inc.) is similar to the Endeavor stent in that zotarolimus is eluted from the thin-strut cobaltalloy BMS platform (in this case, the updated and more deliverable Integrity cobalt-alloy BMS). However, instead of the phosphorylcholine coating of the Endeavor stent, the Resolute stent employs the BioLinx tripolymer coating, consisting of a hydrophilic endoluminal component and a hydrophobic component adjacent to the metal stent surface. This polymer serves to slow the elution of zotarolimus, such that 60% of the drug is eluted by 30 days and 100% by 180 days, making this the slowest rapamycin analogue-eluting DES.

In the single-arm RESOLUTE trial, ZES(R),

117 the primary endpoint of in-stent late lumen loss at 9-months was 0.22 mm, and the in-segment binary restenosis rate was 2.1%, both significantly less than seen with other studies of ZES(E) or BMS. Low rates of MACE, TLR, and ARC definite/probable stent thrombosis were observed. Two-year data from this study have demonstrated TLR, TVR, and TVF rates of 1.4%, 1.4%, and 7.9%, respectively, with no late stent thrombosis events.

118The large RESOLUTE All-Comers randomized trial of ZES(R) versus EES was conducted in 2,292 patients

84; this trial sought to enroll a more unselected patient population than in prior pivotal DES trials. The rate of the primary endpoint of TLF at 1 year was similar to ZES(R) and EES (8.2% versus 8.3%,

P for noninferiority < 0.001). In this trial, the rates of death, cardiac death, MI, and TLR were similar with both stents, but both definite and definite or probable stent thrombosis occurred less frequently with EES at 1 year. Insegment late loss at 13 months (after ascertainment of the primary clinical endpoints) was slightly greater with ZES(R) compared to EES (0.15 mm versus 0.06 mm,

P = 0.04), but there were no differences in rates of binary restenosis among the 460 patients undergoing angiographic follow-up. At 2 years, similar rates of clinical endpoints including TLF, TVF, MI, TLR, and TVR were observed, with a trend toward less stent thrombosis with EES (1.0% versus 1.9%,

P = 0.077), predominantly driven by events within the first year.

97 Three patients in each group (0.3%) had very late stent thrombosis (thrombosis occurring beyond 1 year). One additional investigator-initiated randomized trial of ZES(R) and EES has been reported; in the TWENTE trial

98 1,391 unselected patients were randomized between these two stents. Notably, “off-label” indications occurred in >75% of patients enrolled. At 1 year, the primary endpoint of TVF was similar with both

stents (8.1% versus 8.2%,

P = 0.94), with no observed differences in other clinical endpoints, including stent thrombosis (definite/probable: 0.9% for ZES(R) versus 1.2% for EES).

In summary, the ZES (Resolute platform) is the first stent to demonstrate comparable overall safety and efficacy to the EES, although slight differences in angiographic and clinical outcomes between these stent platforms may exist. Larger studies and longer-term follow-up are required to assess whether these device-specific performance characteristics influence outcomes in actual clinical practice, and whether the long-term safety of this stent is maintained.

Biolimus A9-Eluting Stents (BioMatrix)

The BioMatrix (Biosensors International, Switzerland) stent (BES) elutes biolimus A9 (concentration 15.6 µg/mm), a semisynthetic rapamycin analogue with similar potency but greater lipophilicity than sirolimus, from a stainless steel platform. The stent platform that originally was the S-stent is currently the Juno BMS platform, in the BioMatrix Flex iteration of BES. Of note, the Nobori DES (Terumo Medical Corporation, Japan) is a similar BES that releases biolimus using the same polymer system with a different BMS platform. The Nobori DES has demonstrated favorable results compared to PES and SES in three modest-sized randomized trials.

119,

120,

121 BES are unique, especially compared to the previously described firstand second-generation DES, in that biolimus A9 is eluted from PLLA, a biodegradable polymer which is applied solely to the abluminal stent surface. The biolimus A9 and PLLA are coreleased, and the polymer is converted via the Krebs cycle into carbon dioxide and water after a 6- to 9-month period. Conceptually, such a stent might not be prone to late inflammatory reactions as are occasionally seen with durable polymers, and thus result in improved outcomes after 1 year.

The BioMatrix BES was first tested in the randomized STEALTH trial in which 120 patients with single de novo coronary lesions received either a BES or a bare-metal S-stent.

122 Treatment with BES resulted in lower in-stent late loss at 6 months (0.26 mm versus 0.74 mm for BMS,

P < 0.001). The largest trial examining the safety and efficacy of BES was the LEADERS trial, which randomized 1,707 “all-comer” patients (55% of whom had acute coronary syndromes) to BES versus SES.

123 Similar rates of all clinical endpoints were observed at 9 months with both BES and SES, including the primary study endpoint, which was the composite of cardiac death, MI, or TVR (9.2% versus 10.5%,

P = 0.39). Among the 427 patients allocated to angiographic follow-up at 9 months, in-stent late loss and binary restenosis were similar with both stents. Longer-term follow-up of LEADERS to 4 years has been recently reported (

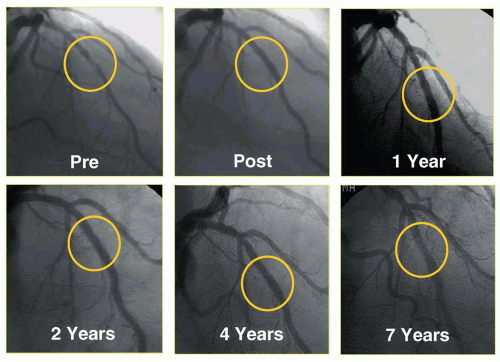

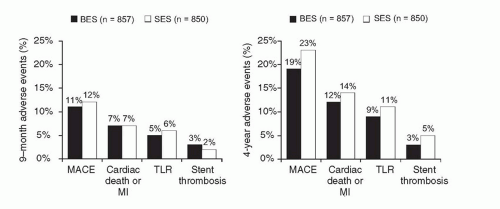

Figure 31.10).

124 Over the entire follow-up period, the rate of the composite primary endpoint of cardiac death, MI, or clinically indicated TVR was lower with BES compared to SES (19% versus 23%,

P = 0.039), with gradual separation of respective event curves over time. Additionally, while overall definite/probable stent thrombosis rates were not significantly different (3% for BES versus 5% for SES,

P = 0.20), the rate of very late definite/probable stent thrombosis was significantly lower with BES (6 events (1%) versus 20 events (2%),

P = 0.005). Similar results were observed when assessing the endpoint of definite stent thrombosis.

Collectively, these data demonstrate that BES has similar efficacy as the first-generation devices, with a favorable safety profile that emerges particularly beyond 1 year. However, much larger and adequately powered studies will be required to determine whether BES, or other devices with bioabsorbable polymers, offer true and sustained clinical advantages to the best-in-class second-generation DES with durable polymers. Several studies investigating these hypotheses are ongoing.