Coronary Artery Disease

This chapter will answer five questions:

What is coronary artery disease and what actually happens in a diseased coronary artery?

What effect does this disease have on the heart and on the body as a whole?

How can coronary artery disease be diagnosed?

How is coronary artery disease treated?

What causes coronary artery disease and how can it be prevented?

Be sure to review the anatomy and names of the major branches of coronary arteries and the abbreviations used to describe them in Chapter 4 (LMCA: left main coronary artery; LAD: left anterior descending branch of the left main vessel; LCA: left circumflex branch of the main left vessel; RCA: right coronary artery).

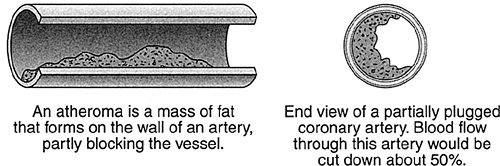

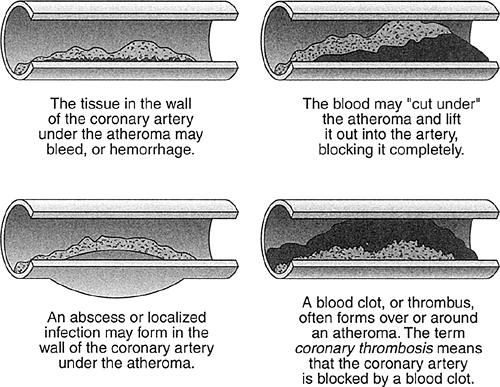

Now study Figures 8-1 and 8-2. You are looking at illustrations of the major cause of death and invalidism in the Western world. These hard masses of fat obstruct the flow of blood through the coronary arteries. Sometimes the blood flow is cut down so much that the heart muscle is injured; sometimes the vessel is completely blocked and the heart muscle dies. The various clinical forms of coronary artery disease are all the result of this basic process.

Types of Disease Produced by Coronary Atheromatosis

Angina Pectoris

Effort Angina

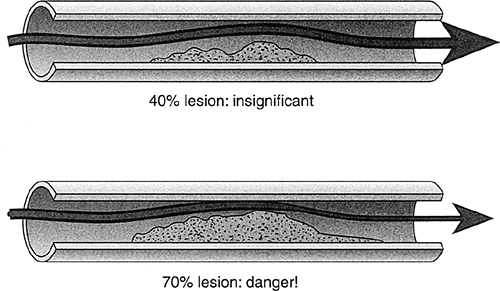

Atheromas (fat deposits within the walls of arteries) form silently. The patient has no way of knowing they exist until they’re large enough to form a significant obstruction to the flow of blood through one or more coronary arteries. What does “significant” mean (Fig. 8-3)?

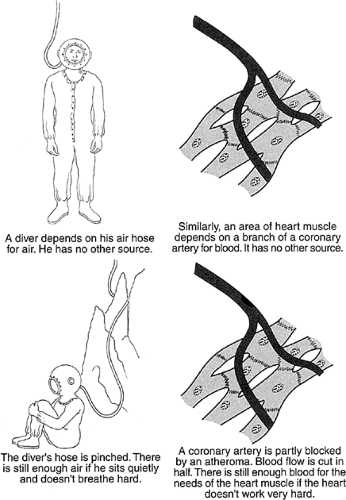

Seventy percent is the magic number. When the atheroma grows to about 70% of the diameter of a coronary artery, it may begin to produce symptoms. The reason is that at this point the blood flow to some area of heart muscle will be barely enough for the needs of that muscle when the patient is at rest and the heart isn’t working very

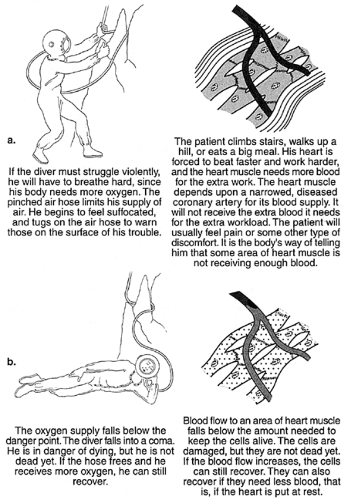

hard. When the heart has to beat faster or when it has to work against a higher pressure, it needs more fuel—blood. It can’t get the extra fuel it needs because of the narrowing in the coronary artery, and the syndrome called angina pectoris results. Study the diver in Figures 8-4, 8-5, and 8-6. Note that in Figure 8-5A he’s tugging on the hose pipe to let someone know he’s not getting enough air. Heart muscle that’s not getting enough blood will often send a message by means of a symptom. The symptom of angina pectoris is painful discomfort somewhere in the upper half of the body: the discomfort comes on with exertion and is relieved by rest.

hard. When the heart has to beat faster or when it has to work against a higher pressure, it needs more fuel—blood. It can’t get the extra fuel it needs because of the narrowing in the coronary artery, and the syndrome called angina pectoris results. Study the diver in Figures 8-4, 8-5, and 8-6. Note that in Figure 8-5A he’s tugging on the hose pipe to let someone know he’s not getting enough air. Heart muscle that’s not getting enough blood will often send a message by means of a symptom. The symptom of angina pectoris is painful discomfort somewhere in the upper half of the body: the discomfort comes on with exertion and is relieved by rest.

Every health care worker must be prepared to recognize the symptoms of angina pectoris, as well as those of coronary insufficiency of any type.

Angina pectoris doesn’t actually mean “pain”: it refers to a sense of “smothering” localized in the front of the chest. It was first described by the English physician William Heberden back in the 18th century. Long before electrocardiograms or x-rays or modern pathology, Heberden deduced that this discomfort came from the heart. His younger colleague, Edward Jenner, wrote to him describing an autopsy he had carried out on a victim of angina at Bath. Jenner noted a “white, fleshy protuberance” blocking a coronary artery and guessed that this was the cause of the angina. (Jenner also discovered the smallpox vaccination, thereby saving more lives than anyone in the history of the human race.)

TABLE 8-1 How to Recognize Coronary Pain | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Here are the symptoms of anginal pain to look out for (Table 8-1):

Most common and most specific: a sense of pressure anywhere in the front of the chest, often radiating up into the neck. The pain may be low in the chest, below the end of the sternum, or actually in the upper abdomen—that’s why it’s often mistaken for indigestion.

The next most common site of pain is the arms: most often the left arm, sometimes both arms, rarely just the right.

Unusual locations: I have seen several patients with well-documented anginal pain localized under the left shoulder blade. In another, the pain was localized in the left wrist. It’s safe to say that pain anywhere in the upper half of the body that comes on with exertion and is relieved by rest should be considered angina until proved otherwise.

Character of pain: Most patients think of pain as the sensation you feel when you’re stabbed with a knife or stuck with a pin. It’s important to explain that these are not the sensations you’re talking about when you ask about heart pain. It’s common to hear a patient say “I don’t feel pain, just a heavy sensation in my chest.” At this point an experienced cardiologist will always interrupt and explain that this “heavy sensation” is a common form of heart pain.

“Heaviness,” “pressure,” or “fullness in the chest” are the most common terms used to describe angina, but they are by no means the only ones. “Tingling and burning,” “a feeling as if my heart’s too big for my chest,” “sudden, severe anxiety,” “fullness and pounding in the head and neck,” and “an aching feeling, like I’ve pulled a muscle” are all symptoms recorded during angina pectoris. The

insufficient blood supply may interfere with the pumping action of the heart. As a result, the patient may simply become very short of breath.

One more time: The common denominator of all symptoms of the classic, typical form of angina pectoris is that the symptoms come on with exertion and are relieved by rest. Exertion like what? Exertion like walking, climbing stairs, or lifting or carrying loads, for instance. Isometric stress, or straining against a heavy weight, is especially dangerous. That’s why snow shoveling often brings on coronary pain. A large meal is a type of exertion most people overlook, but it can be important. A large meal throws about the same load on the heart as walking up three flights of stairs. King Henry VIII was said to have died of a “surfeit of lampreys.” In fact, he overstuffed the royal gullet and had a heart attack. Sudden emotional stress can cause the blood pressure to rise and the heart to beat faster. Angina can result.

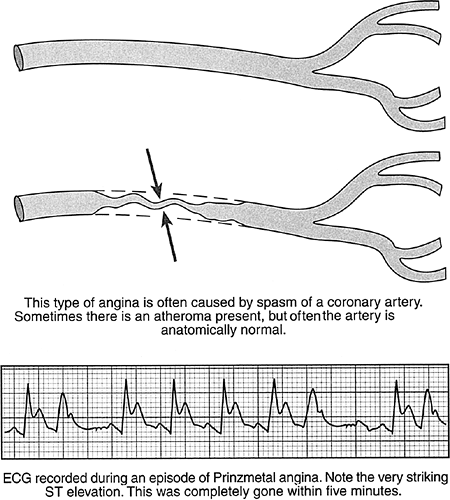

Prinzmetal Angina

Myron Prinzmetal, an American cardiologist, described another type of angina, commonly known as the “intern’s nightmare.” It doesn’t fit any logical pattern. The pain often comes on at rest, even though the patient doesn’t feel any discomfort during exercise. It may waken patients during the early morning hours. This kind of angina is usually caused by spasm or constriction of a coronary artery. Sometimes it happens in diseased arteries, but it can also take place in completely normal vessels. Fortunately, this type of angina is rare, and it can usually be diagnosed by changes in the electrocardiogram (Fig. 8-7).

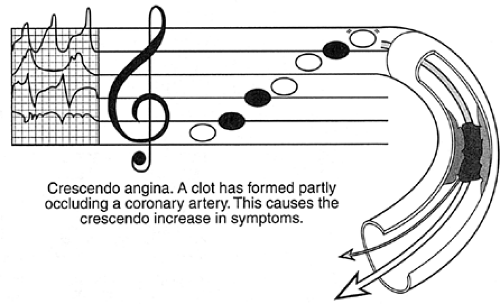

Crescendo Angina: Coronary Insufficiency

When a musical score reads “crescendo,” it means “play louder and louder, progressively.” That’s a good description of this dangerous type of angina. The pain comes on more often, or it’s more severe, or it comes on with less effort—sometimes all three. In an especially dangerous form of crescendo angina, the pain comes on at rest or wakens the patient from sleep, especially in the early morning hours. It’s now clear that when this happens a blood clot has started to form at the diseased, narrowed spot in the artery. The clot doesn’t block the artery completely, but it cuts down flow below the danger point and there is the beginning of damage to the heart muscle (Fig. 8-8). Complete closure and sudden death are immediate risks. The patient with crescendo angina must be put in a hospital at once. The pain may last longer than in typical angina—sometimes as long as 30 minutes. The term coronary insufficiency is often used in these cases. Again, the combination of a clot and an atheroma is responsible and the risk is the same as in crescendo angina. Note the predicament of the diver in Figure 8-5 and you’ll have a good idea of what goes on in crescendo angina and coronary insufficiency.

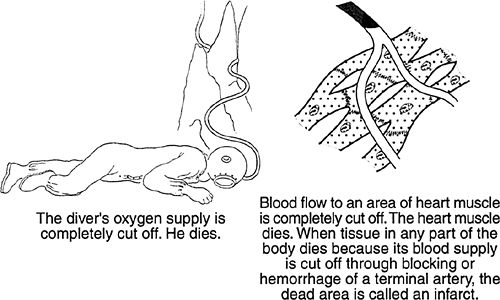

Myocardial Infarction

This is the full-blown “heart attack.” The word infarct means that an area of tissue has died because its blood supply has been cut off. Myocardial infarction means that an area of heart muscle has died because a coronary artery has been completely blocked. It is now certain that this happens because of a blood clot that forms in a diseased, narrowed part of a coronary artery. The word for clot is thrombus, hence the common term “coronary thrombosis.”

Note our unlucky diver in Figure 8-6. The most common symptom of myocardial infarction is pain, often exactly like the pain of angina pectoris, except that it doesn’t go away. The pain of infarction can be so severe the victim can hardly stand it, or it may be so mild that it’s passed off as heartburn or neuralgia. In Framingham, Massachusetts, a large number of autopsy records were examined. To everyone’s surprise, 25% of the patients whose hearts showed the scars of infarcts had no medical history of any kind. In other words, about a quarter of all infarcts are “silent.” The victim never knows they happened.

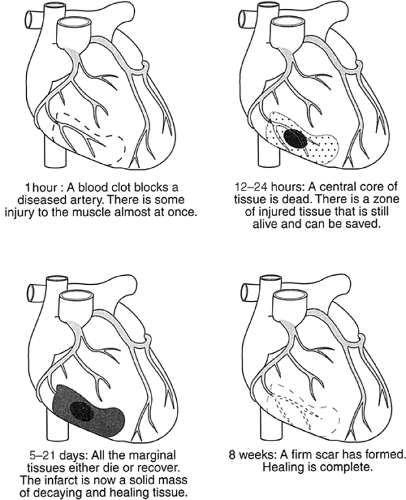

What happens to the heart muscle in an infarct? Figure 8-9 explains the sequence of events.

What’s the risk of myocardial infarction? It’s high. Fifty percent of people who suffer a myocardial infarct die on the spot before medical aid can be summoned. Once the patient reaches the hospital, on the other hand, the risk is very small: the risk of dying of a first heart attack in a properly staffed coronary care unit with conservative medical management is only 7%.

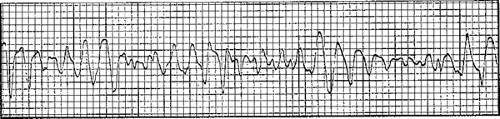

Why do people die after a myocardial infarct? First, the heart may stop its regular beating and go into a fast, feeble twitching, called ventricular fibrillation. The patient drops as if shot, and death follows within 10 minutes (Fig. 8-10).

Second, the amount of muscle destroyed may be large enough to weaken the pumping action of the heart: congestive heart failure follows. If 30% or more of the muscle

mass of the left ventricle is destroyed, there won’t be enough pump to sustain life and the patient will die. Third, the patient may go into cardiogenic shock—this is usually fatal.

mass of the left ventricle is destroyed, there won’t be enough pump to sustain life and the patient will die. Third, the patient may go into cardiogenic shock—this is usually fatal.

What is shock? This is one of the most important definitions for any health worker to have firmly in mind. Shock has nothing to do with coming home and finding your house on fire. The medical definition of shock is simple: there isn’t enough blood circulating through the tissues of the body to keep them functioning.

The simplest kind of shock to understand comes from hemorrhage: someone loses a great deal of blood quickly and there isn’t enough left to support the needs of the body.

There are more complicated causes of shock. Overwhelming infection may produce shock by shunting blood into internal reservoirs where it can’t be used. This is called septic shock.

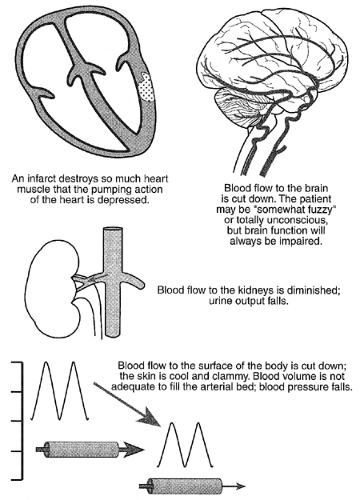

Cardiogenic shock results from a massive myocardial infarct that destroys so much ventricular tissue that there isn’t enough forward flow out of the heart to support the rest of the body (Fig. 8-11). This inadequate blood flow produces changes in the function of four key areas of the body. These changes are easy to detect and the physician can usually establish the diagnosis within minutes.

Cardiogenic shock is very dangerous. The mortality has traditionally been about 80%. Modern means of treatment have improved the outlook somewhat, but the grim fact remains that cardiogenic shock is fatal more often than not.

The Diagnosis of Coronary Artery Disease

If coronary artery disease doesn’t produce symptoms, it probably won’t be detected. Actually, the word symptoms is misleading: it should be symptom because there’s only one. Painful discomfort of some type is the only symptom of coronary artery disease in the vast majority of cases. It’s usually the only warning the patient gets.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree