Conjoined Twins and Ectopia Cordis

Joseph J. Amato

Birth of conjoined twins (twins whose bodies are connected at some level) is indeed very rare and estimated by various authors as 1 in 50,000 to 100,000 births. A majority (40% to 60%) are stillborn and 35% do not or cannot survive after birth. They are associated with a high incidence of maternal polyhydramnios, prematurity, and low birth weight. They are always the same sex and approximately 70% are female. Isomerism is common: twins are born with two right sides, two left sides, in mirror images of normal anatomy, or a mixture of the two with shared organs.

HISTORY

There are numerous historical accounts of the existence of conjoined twins. The earliest recorded history was found in ceramics of ancient Peru in 300 AD.

History then records two Arabian brothers who were joined with ones leg to the others head. They were separated with a sword in 750 AD.

The most famous report described “Siamese Twins” which gave a new popular synonym that is often substituted for “Conjoined Twins.” These were the historical twins named Eng and Chang who were born in Siam in 1811 (now Thailand but really they were Chinese) sharing a common liver and joined at the abdominal area. King Rama ordered them to death because he believed that they represented a sign of an evil omen. Later, this decree was withdrawn. Interestingly, they joined the circus, settled in America, married two sisters, had 22 children, became successful businessmen and ranchers, and settled in Wilkes County, NC. In January 1874, Eng woke up to find Chang dead; thus, both died at the age of 63. The social element of this subject of marriage to two separate sisters, a “bed for four,” and after a severe argument between the sisters the creation of two separate “homesteads,” created a fascinating account. Conjoined twins are not limited to any racial or ethnic group.

Also famous were the Biddenden Maids born together in 1100 and who died together in 1134.

There appeared to be an epidemic of conjoined twinning in South Africa and in Sweden; this cluster of births has, however, been disputed.

There are also published accounts of conjoined twins occurring in cattle, rabbits, cats, hamsters, pigs, rats, and mouse.

MECHANISM OF CONJOINED TWINNING

There are two theories of the mechanism of conjoined twinning (which are incompletely understood and are contradictory). One theory is called “fission” in which there is an incomplete and asymmetrical partial splitting of a single embryonic fertilized egg. The second theory is called “fusion” in which the fertilized egg was destined to become completely separate twins but then stem cells search for like stem cells on the other twin (due to their close proximity) then fuse together. One author states that the “fission” theory is more widely acceptable; however, now the “fusion” theory is stated to look most probable. If the splitting or rejoining of the fertilized egg occurs after 12 days with either theory, the result will be a conjoined twin.

ETIOLOGY OF CONJOINED TWINS

Conjoined twins are monozygotic (one egg) and are monoaminiotic and monochorionic. The one amnion is the inner layer that holds the embryo and later the fetus within the amniotic fluid. The chorion is the inner membrane that contains the embryo and part of the placenta. It is known that twinning may tend to be prevalent in some families.

While the etiology of either fission or fusion may be disputed, various teratogenic agents may influence the incidence of conjoined twins. These may include:

The use of gonadotropins, which are fertility drugs for women and hormonal imbalance in men.

Experimental studies in animals demonstrate that general and local anesthetics, acetaldehyde (a metabolite of ethanol), and some tranquilizers may induce conjoint twinning.

Another cause has been shown to be lack of calcium and magnesium salts.

Seven cases (two published) have been reported in which conjoined twinning occurred with the use of clomiphene for induction of ovulation.

Maternal exposure to valproic acid has been reported when used as an anticonvulsant or with the use of valerian, a common moodstabilizing agent.

Fungistatic agents as griseofulvin (used as a fungicide) also has been associated with conjoined twins.

Agent Orange and other herbicides. There has been a marked increase in conjoined twins in Vietnam due to Agent Orange and other herbicides.

CLASSIFICATION OF CONJOINED TWINS

A general nomenclature has been established for all types of conjoined twins. Twins are classified according to the common area of the body onto which their bodies are joined and the ending “pagus” from the ancient Greek language is added which means “fixed.”

Spencer provides a classification of eight different types of conjoined twins: parapagus (26%), thoracopagus (25%), omphalopagus (17%), cephalopagus (11%), ischiopagus (9%), pygopagus (6%), craniopagus (5%), and rachipagus (2%). However, this classification is difficult to follow for the cardiothoracic surgeon because thoracopagus and omphalopagus often coexist. Several alternative classifications are more useful for cardiothoracic surgeons. In one classification, the types in alphabetical order are described as anterior (front), posterior (back), lateral (side), and ventral (area of abdomen).

This classification specifies the types of twins, which either have two hearts, one

shared heart, and a possible involvement of the heart in these infants. When indicated there is involvement of the heart in most cases and possible involvement in some cases.

shared heart, and a possible involvement of the heart in these infants. When indicated there is involvement of the heart in most cases and possible involvement in some cases.

Ventral union (referring to the front of the body, faces, four ears, and two bodies)

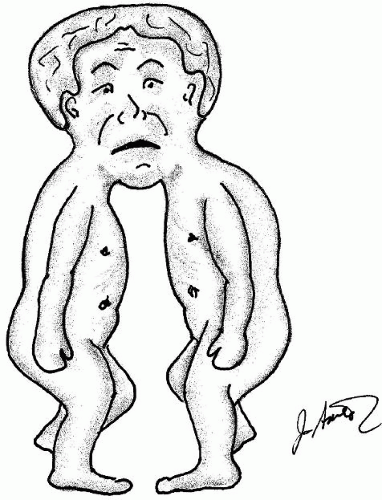

Cephalopagus: Twins joined at the upper part of the body with one head. They are joined by one face with two bodies. There is one face with four ears. These types are extremely rare and do not survive (Fig. 108.1).

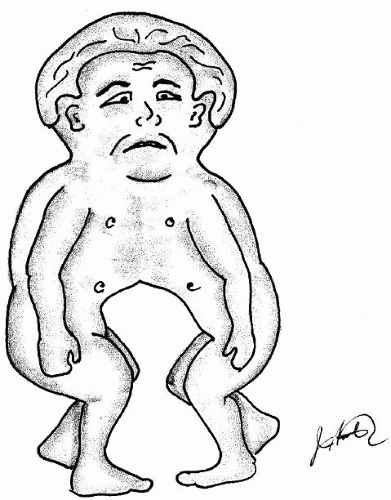

Cephalothoracopagus (cephalothoracopagus syncephalus, epholothoracopagus, craniothoracopagus): Joined at head and thorax. There are two faces, one brain, one head, usually share one heart and fused gastrointestinal tracts (Fig. 108.2).

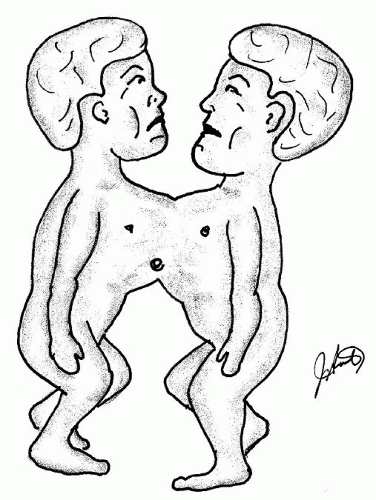

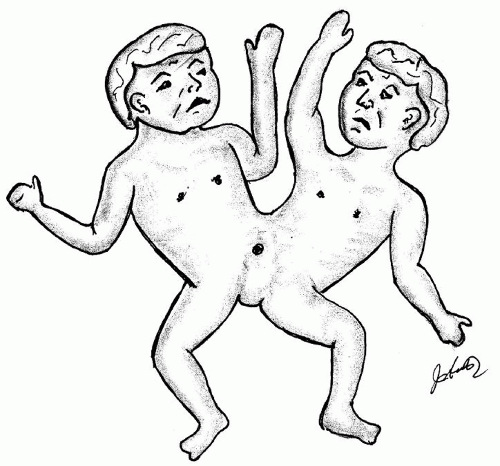

Thoracopagus: Joined at upper thorax to umbilicus. Shared heart in 90% and 75% have a joined heart which cannot be separated, four arms, four legs, and two pelvises (Fig. 108.3).

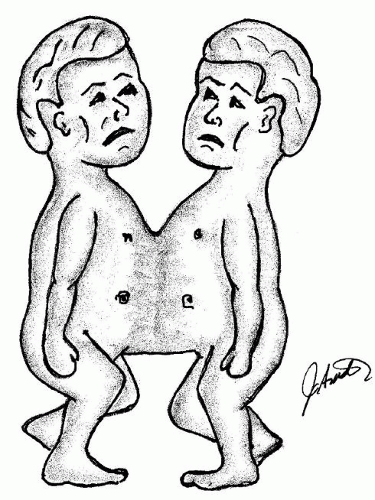

Omphalopagus: Joined in the area of the umbilicus, sometimes thorax, however, not affecting the heart. Two pelvises, four arms, and four legs (Fig. 108.4).

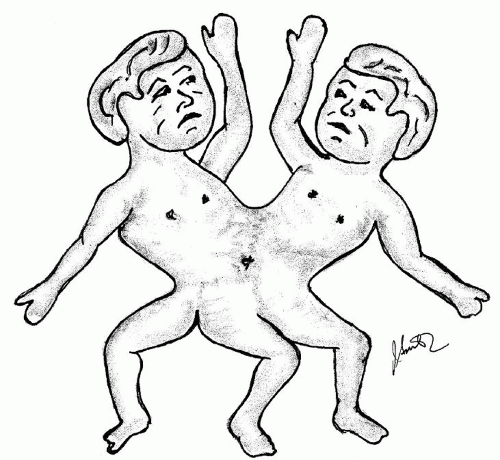

Thoraco-omphalopagus: A combination of thoracopagus and omphalopagus. Joined at upper thorax to the umbilicus and usually share a heart. Ninety percent have a common pericardium and 75% have a shared heart. They have four arms and legs. Xiphoomphalopagus look similar but their hearts are normal (Fig. 108.5).

Xiphopagus (a subset of omphalopagus): Joined at the xiphoid from lower sternum (gladiolus) to the umbilicus (Fig. 108.6).

Ischiopagus: Twins joined at the level of the umbilicus end to end with the spine. There are four arms with various combinations of legs. Of the above types, there may be only two legs present (ischiopagus dipus), three legs present (ischiopagus tripus), or four legs present (ischiopagus tetrapus/quadripus).

Omphalo-ischiopagus: A combination of omphalopagus and ischiopagus are similar to ischiopagus twins facing each other. There can be cases of thoraco-omphaloischiopagus and xipho-omphaloischiopagus twins who are joined facing each other but are joined at the chest.

Lateral union (referring to twins joined side by side with shared umbilicus, abdomen, and pelvis. These rarely involve the heart.

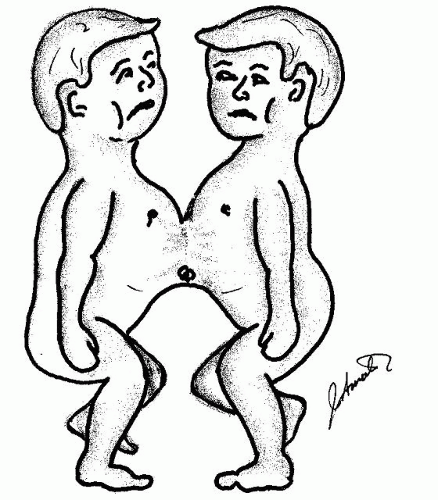

Parapagus: Twins joined at the pelvis with one symphysis pubis and one or two sacrums (Fig. 108.7).

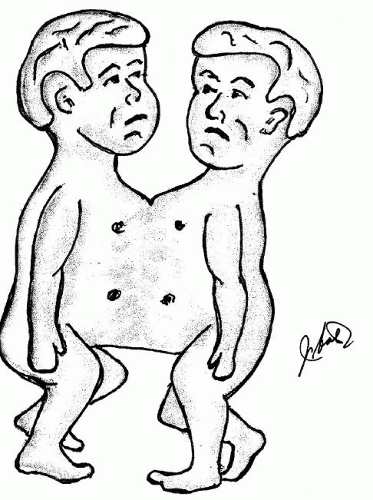

Dithoracic parapagus: Twins joined at the abdomen and pelvis but not the thorax (Fig. 108.8).

Dicephalic parapagus (dicephalus): Twins joined at the abdomen, pelvis, and thorax. All of the above may have two arms (dibrachius), three arms (tribrachius), and four arms (tetrabrachius).

Dorsal union (referring to twins joined at the dorsal aspect (at the back). In these twins, there is no involvement of the thorax and abdomen.

Craniopagus: Twins joined at the skull except for the face.

Pygopagus (pyopagus or illeopagus): Twins joined at the sacrococcygeal, perineal, and occasionally the sacrum.

Rachipagus: Twins fused dorsally above the sacrum and the lumbar spine. This type is very rare. The above classification constitutes one of many and excludes many other rare types. Two of these types are:

Parasitic twins (asymmetrical, unequal) in which if one dies or

receives inadequate nutrition while in the uterus then one embryo maintains dominant development at the expense of the other.

A cardiac twin is an incomplete twin without a heart that grows separately and receives nourishment from its normal twin.

A second simpler classification listing the frequency of conjoint patterns is as follows:

Thoraco-omphalopagus (twins joined at the chest, abdomen, or both)—74%.

Thoracopagus or xiphopagus (joined at the chest)—40%.

Omphalopagus (joined at the abdomen) —34%.

Pyopagus (joined at the buttocks)—18%.

Ischiopagus (joined at the ischium)—6%.

Craniopagus (joined at the head)—2%.

CARDIAC INVOLVEMENT IN CONJOINED TWINS

For the purpose of this chapter, while other types of twins are possible, our concern is twins with involvement of the cardiovascular structures. These twins are all joined primarily in the thoracic area. There may be either a single heart or partial duplications of cardiac and vascular elements. There can also be two hearts with extensive sharing of the vascular elements. The sternum is either partially or totally absent in all cases, the pericardium in 90% and the hearts fused in 75%.

The other organs that can be involved include the unusual saddle-shaped liver, a joined common duct (while the gall bladders and hepatic ducts might be separate), and hepatic veins either separate or shared. There can be persistent left superior vena cavae, which drain into separate atria. Also obviously, there is a great variation of gastrointestinal tracts. Obviously, those

with two hearts, each with one heart in a thoracic cavity, have a better chance of survival.

with two hearts, each with one heart in a thoracic cavity, have a better chance of survival.

One of the most difficult tasks is to present a classification of the morphology and anatomical arrangement of the heart or hearts in these twins. A simple general classification has been presented by Ambar:

Group A: Separate hearts, separate pericardium.

Group B: Separate hearts, common pericardium.

Group C: Fused atria, separate ventricles.

Group D: Atrial and ventricular fusion.

With the above cardiac abnormalities, one must consider the other associated various organ systems, with either multiple or incomplete formation of the liver, intestines, and urinary systems.

The most common atrial malformations include a single atrium with atrial septal defects. The most common ventricular malformations are a single ventricle and large ventricular defects. Combined pulmonary arteries and aorta have not been reported. Of the others, any combinations of basic defects have been described: D-transposition, interrupted aortic arch, and pulmonary stenosis and atresia.

Successful separation of thoracopagus twins in cases of conjoined heart is difficult. There has been only a single report of successful separation of a conjoined heart and in this instance it was conjoined atria. In a series of 13 surgeries on conjoined twins in The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, PA none of the patients with complex fused hearts survived even after sacrificing one of the twins. Cases of thoracopagus conjoined twins with normal separate hearts, common pericardium, anomalous systemic venous drainage, fused atria, and atrial septal defects have been successfully separated.

DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES IN CONJOINT TWINS

There are two phases of diagnosing the presence of conjoined twins: early in the prenatal period and then following delivery. Evaluation of the extent of pathological patterns of both the cardiovascular system and other involved organs that can potentially affect the question of infant separation and survival of both twins is necessary. For the fetuses, prenatal ultrasound has been used as early as 1960 and with more modern techniques, the use of transvaginal ultrasound may give the diagnosis as early as 7 to 14 weeks into the pregnancy.

Prenatal magnetic resonance imaging has better established the intricate shared multiple organs of the fetus. Magnetic resonance imaging has the advantage of being capable in twins to determine the systems of blood flow and the production of three-dimensional and multislice imaging, which can clarify the venous and atrial anatomy.

Early imagery allows proper counseling with regard to prognosis, management, and if indicated, termination of pregnancy. One interesting case diagnosed with a fetal echocardiogram was the condition never reported prior to the year 2000 of a single heart in conjoined twins diagnosed by the pumping of blood though the cord from the one infants single heart to create circulation in the noncardiac infant. The delivery of the two and the cutting of the cord would cause both infants to die. Surgery was performed by a caesarian section. Separation of the infants caused immediate death of the infant without the heart. At separation, the heart did not fit into the chest and protruded in a similar manner to an ectopia cordis. A rib cage was created from the chest wall from the twins tissues. The second infant was alive at 14 months at the time of this report.

ANESTHETIC MANAGEMENT OF CONJOINED TWINS

Perioperative management includes monitoring, airway and fluid management, ventilator support, and anesthetic medications. There are usually two teams of anesthesiologists. There are obviously difficulties in the positioning of the twins; body alignment is of utmost importance because of the ability to intubate because of the various anatomic positions and single or multiple airways, and only the use of airway masks if intubation is impossible. The management of the potential dead twin upon separation is too variable to explain. In a rare case in which one twin had a rudimentary heart and there was severe cardiac dysfunction in the possible normal twin, a method of intubation (an EXIT procedure [ex utero intrapartum treatment]) is performed immediately after the extraction of the fetus from the womb and separation of the dead twin. Prior to cutting of the umbilical cord, the surviving twin is either intubated or tracheostomy is performed.

In many of the twins, there is also marked difference in the twin’s circulatory systems, which present with different arterial blood pressures and atrial oxygen saturations.

SURGICAL SEPARATION

The surgical separation of conjoined twins is a delicate and risky procedure, requiring extreme precision and care. Decision to separate twins is a serious one. In 1689, Konig performed the first recorded separation of twins joined at the umbilicus with a ligature. There have been approximately 250 successful operations in which either one or both twins have survived. Of 47 pairs of surgically separated thoracopagus (omphagothoracopagus) twins with completely separate hearts only 42 survived (70%), and in 5 patients with only atrial connections, only 1 patient survived. In nine patients with both atrial and ventricular connections, there were no survivals. The site of the anatomical pericardial and/or cardiac conjoined areas is the most important consideration of a successful outcome.

Once separation is successfully achieved, tight closure of the pericardium and large abdominal and thoracic defects should be avoided. Silastic sheeting or the author’s preference of a thin polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane should be used. Skin coverage of the separated areas is necessary. Skin flaps, as in ectopia cordis, can be used. In one case, the chest wall of the nonsurviving twin was used. Other surgeons have used a resin called “Cranioplastic” (commonly used by neurosurgeons, to create a “resin plate”). In other cases, siliconized rubber sheets, acrylic materials, and another resin mesh made of polypropylene mesh have been utilized. In the authors surgical management of ectopia cordis, a Gore-Tex® material (PTFE by Gore) was used to stabilize the chest, which was then covered by skin. This can be accomplished by raising skin flaps or use of the expired twins’ redundant skin, or use of tissue expanders if separation can be delayed for a few months.

ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR CONJOINED TWINS

Surgical separation of conjoined twins that results in the death of one of the twins raises complex legal, moral, ethical, religious, and financial issues.

Conjoined twins raise the ethical issue of “Is it justified to sacrifice one life to save another.” Ethical issues arise for each of the twins in which the following apply:

There is a law of conduct, namely, “Thou shall not kill.”

Natural law demands us not to harm anyone’s health, liberty, or possessions.

The medical staff understands that life is sacred where every life is equally valuable. The problem lies in analyzing each of the twin’s different anatomies and chances of survival.

A suggested approach is as follows: (a) the parents meet the team that is to care for the children. (b) Confidentiality is maintained. (c) Parents speak with their religious advisors. (d) The public relations department maintains a level of guarding the interests of the children and family. (e) Legal advisors consult with the Law Courts and protect the surgeons from accusation of wrongful acts, which might lead to prosecution.

CONGENITAL WALL DEFECTS (ECTOPIA CORDIS)

Ectopia cordis is classified within the broad spectrum of congenital chest wall deformities, which include (1) pectus excavatum; (2) pectus carinatum; (3) Poland’s syndrome; (4) sternal cleft defects that include ectopia cordis; and (5) other miscellaneous conditions. Thus, reviewing ectopia cordis is necessary to understand sternal cleft defects and separate ectopia cordis from the other isolated sternal cleft anomalies. The embryological failure of the fusion of the sternal bars within this category create a complete or partial separation of the sternum.

The three categories of chest wall defects include:

Isolated sternal clefts: These occur within the upper sternum and there is normal skin coverage; the heart is within the sternum; the pericardium is intact; the diaphragm is normal; and omphaloceles do not occur. These patients seldom have intrinsic congenital heart disease.

Ectopia cordis: The various forms of ectopia cordis are often associated with other midline defects, which include intrinsic cardiac defects, complete or partial absence of pericardium, omphalocele, and ventral diaphragmatic hernia.

DEFINITION OF ECTOPIA CORDIS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree