Depression has been associated with adverse outcomes after acute coronary syndrome, including ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). However, trends over time in the incidence and inhospital treatment of STEMI for patients with co-morbid depression in the current era are unknown. We conducted a serial, cross-sectional analysis of patients with STEMI (weighted n = 3,057,998) in the National Inpatient Sample from 2003 to 2012. We examined trends in STEMI incidence and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for patients with and without depression. We used multivariate logistic regression to assess observed differences and to explore trends in inhospital mortality. Depression was present in 153,180 (5%) of the sample. Patients with depression were more likely to be female (55% vs 37%), of white race (86% vs 78%), and had lower crude mortality (12.0% vs 14.2%; p <0.001 for all). Over time, STEMI incidence decreased 52% in patients without depression (p for trend <0.001) but remained stable in those with depression (p for trend 0.74). Although the use of PCI increased in all subgroups over the study duration (p for trend <0.001), depression was associated with lower adjusted odds of PCI (odds ratio 0.90, 95% confidence interval 0.89 to 0.92, p <0.001). In conclusion, in contrast to the wider population, the incidence of STEMI is not decreasing in patients with co-morbid depression. Patients with STEMI and co-morbid depression are less likely to receive revascularization therapy with PCI. These concerning differences warrant further attention.

Over the last 2 decades, there has been a decrease in the incidence of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), particularly ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The inhospital mortality of STEMI has also decreased, in part owing to the expanding use of primary revascularization therapy with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Amidst this broader landscape, it is unknown whether similar trends exist in patients with STEMI with co-morbid depression. This is of importance given that numerous investigations have identified an elevated prevalence of depression in patients with ACS, and such patients appear to have a worse prognosis. Furthermore, there are data suggesting that pre-existing depression may itself be a risk factor for incident ACS, although this association remains to be fully elaborated. We, therefore, examined trends in the incidence of STEMI and revascularization therapy in patients with and without depression in a nationally representative database. We also aimed to explore trends of inhospital mortality in these subgroups over the same time period.

Methods

Data were obtained from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project—National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample (NIS) files from 2003 to 2012. From 2003 to 2011, the NIS represented a 20% stratified sample of all community nonfederal US hospitals. Starting in 2012, the NIS was redesigned to represent 20% of all discharges from nonfederal US hospitals, representing 94% of all discharges from US community hospitals. Discharges are weighted based on the sampling scheme to permit inferences for a nationally representative population. Each record in the NIS includes the procedure and diagnosis codes recorded for each patient’s hospital discharge summary. In 2012, the NIS contained de-identified information for 7,296,968 discharges from 4,378 hospitals in 46 states, representing 36,484,846 discharges.

From January 2003 to December 2012, hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarction were selected by searching for the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification ( ICD-9-CM ) codes for initial acute myocardial infarction 410.x1, a method previously reported as having high validity in multiple cohorts. Patients with missing age data (n = 345) and ICD-9 codes 410.7x (non-STEMI) were excluded from analysis, leaving only patients with STEMI. The incidence of STEMI was calculated as the annual weighted number of patients with STEMI divided by 20% of the estimated US adult population of that year.

Patient- and hospital-level variables were included as baseline characteristics. Co-morbidities were identified using standard Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality variables (based on Elixhauser methods). Co-morbidity burden was also summarized with the Elixhauser index. Co-morbid depression was identified using the secondary ICD-9-CM codes 296.2x, 296.3x, 300.4, and 311, which have been demonstrated to have a high positive predictive value in previous work. Codes for personality disorder were not included in the definition of depression. Patients with a concomitant diagnosis of cardiogenic shock were identified using ICD-9-CM code 785.51. We used ICD-9-CM procedure codes to identify patients who underwent PCI (00.66, 36.01, 36.02, 36.05, 36.06, and 36.07) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) (36.1x).

Crude trends in STEMI incidence and revascularization were plotted on graphs and evaluated using the autoregressive integrated moving average model for time series. To better evaluate trends in PCI over the study duration, we created univariate and multivariable logistic regression models to assess for within-group differences in the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) compared with the 2003 year data. Next, we used logistic regression models to assess the association between depression and revascularization, using the absence of depression as the reference group. Model covariates were selected through backward stepwise testing with a retention threshold of p <0.10. Candidate covariates included demographics, hospital characteristics (bed size, region, location, and teaching status), pertinent Elixhauser co-morbidities (alcohol use, anemia, connective tissue disease, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, coagulopathy, diabetes, drug abuse, fluid/electrolyte disorders, hypertension, liver disease, metastatic cancer, neurologic disorders, obesity, peripheral vascular diseases, pulmonary circulation disorders, psychotic disorder, renal failure, solid tumor, valvular disease, and weight loss), previous PCI and/or CABG, hemodialysis, and cardiogenic shock. As an exploratory analysis, we constructed additional models with similar candidate variables (and also an additional variable for the performance of inpatient revascularization) to analyze within- and between-group differences of inhospital mortality.

For descriptive analyses, we compared baseline demographics and hospital characteristics between patients with and without depression. Continuous variables are presented as means or medians as appropriate; categorical variables are expressed as frequencies (percentages). To compare baseline characteristics and inhospital care patterns with respect to depression, either Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon nonparametric tests or the Student’s t test was used for continuous variables, and Pearson chi-square tests were used for categorical variables. For all regression analyses, the Taylor linearization method “with replacement” design was used to compute variances. Regression analyses were a priori tested in both women and men separately and according to the presence of cardiogenic shock given its adverse effect on outcomes and independent indication for revascularization. Other interaction testing was carefully considered. All statistical tests were 2 sided, and a p value <0.05 was set a priori to be statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and SPSS (version 22; IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York).

Results

There were 3,057,998 patients with STEMI who were included for analysis. Among the STEMI cohort, 153,180 patients (5%) had depression. Patients with depression were of similar age to those without depression, but they were more likely to be female and of white race ( Table 1 ). Although most individual co-morbidities were more prevalent in the depression cohort, the mean Elixhauser index (with higher values indicating increased cumulative co-morbidity) was higher in patients without depression. Patients with depression were more likely to be covered by Medicare and to be hospitalized at smaller and rural hospitals. In patients with depression, cardiogenic shock was less common, mean length of stay was slightly shorter, and discharge to home was less frequent. Overall inhospital mortality was significantly lower in patients with depression.

| Variable | Depression | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 2,904,818) | Yes (n = 153,180) | ||

| Age (mean, SD) | 66.5 ± 14.8 | 66.6 ± 15.3 | <0.001 |

| Age (median, IQR) | 67 (55-78) | 66 (55-80) | <0.001 |

| Female | 1078086 (37.1%) | 84350 (55.1%) | <0.001 |

| White | 1761305 (78.4%) | 105075 (85.7%) | |

| Black | 187103 (8.3%) | 6636 (5.4%) | |

| Hispanic | 160805 (7.2%) | 6281 (5.1%) | |

| Asian | 50839 (2.3%) | 182 (1.0%%) | |

| Native American | 12106 (0.5%) | 585 (0.5%) | |

| Other | 73394 (3.3%) | 2787 (2.3%) | |

| Alcohol Use | 81484 (2.8%) | 6491 (4.3%) | <0.001 |

| Anemia | 327691 (11.4%) | 25240 (16.6%) | <0.001 |

| Cardiogenic Shock | 244144 (8.4%) | 9318 (6.1%) | <0.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 131607 (4.6%) | 5970 (3.9%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 516355 (17.9%) | 37282 (24.5%) | <0.001 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 182929 (6.4%) | 10639 (7.0%) | <0.001 |

| Connective Tissue Disease | 52451 (1.8%) | 4691 (3.1%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | |||

| Without complication | 667258 (23.2%) | 38521 (25.3%) | <0.001 |

| With complication | 111404 (3.9%) | 7706 (5.1%) | <0.001 |

| Drug Abuse | 52483 (1.8%) | 5255 (3.4%) | <0.001 |

| Fluid/Electrolyte Disorders | 579465 (20.1%) | 34928 (22.9%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1612164 (56.0%) | 98138 (64.4%) | <0.001 |

| Liver Disease | 30042 (1.0%) | 2166 (1.4%) | <0.001 |

| Metastatic Cancer | 32884 (1.1%) | 1724 (1.1%) | 0.72 |

| Neuro Disorders | 153988 (5.3%) | 15334 (10.1%) | <0.001 |

| Obesity ∗ | 239530 (8.3%) | 18030 (11.8%) | <0.001 |

| Paralysis | 47039 (1.6%) | 4098 (2.7%) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 229075 (8.0%) | 13947 (9.2%) | <0.001 |

| Prior coronary bypass | 129690 (4.5%) | 7797 (5.1%) | <0.001 |

| Prior coronary stent | 228971 (7.9%) | 13117 (8.6%) | <0.001 |

| Psychotic Disorder | 38662 (1.3%) | 14057 (9.2%) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary Circulation Disorder | 20449 (0.7%) | 1731 (1.1%) | <0.001 |

| Renal Failure | 305073 (10.6%) | 16997 (11.2%) | <0.001 |

| Hemodialysis | 9754 (0.3%) | 704 (0.5%) | <0.001 |

| Solid Tumor | 42383 (1.5%) | 2274 (1.5%) | 0.5 |

| Valvular Disease | 49857 (1.7%) | 2987 (2.0%) | <0.001 |

| Weight Loss | 76559 (2.7%) | 5139 (3.4%) | <0.001 |

| Elixhauser Index (mean ± SD) | 3.0 ± 5.4 | 0.8 ± 5.9 | <0.001 |

| Payer | <0.001 | ||

| Medicare | 1536939 (53.0%) | 89493 (58.5%) | |

| Medicaid | 163618 (5.6%) | 11506 (7.5%) | |

| Private | 903317 (31.2%) | 39718 (26.0%) | |

| Self-Pay | 190435 (6.6%) | 7127 (4.7%) | |

| Hospital Size (by bed number) | <0.001 | ||

| Small | 313372 (10.8%) | 18871 (12.4%) | |

| Medium | 675402 (23.3%) | 37201 (24.4%) | |

| Large | 1903745 (65.8%) | 96313 (63.2%) | |

| Income Quartile (based on Hospital Zip Code) | <0.001 | ||

| 1 st | 797045 (28.1%) | 41207 (27.5%) | |

| 2 nd | 779819 (27.5%) | 41612 (27.8%) | |

| 3 rd | 679830 (24.0%) | 36907 (24.6%) | |

| 4 th | 575533 (20.3%) | 30079 (20.1%) | |

| Hospital Location | <0.001 | ||

| Rural | 355245 (13.2%) | 21585 (15.7%) | |

| Urban | 2325894 (86.8%) | 115730 (84.3%) | |

| Hospital Region | <0.001 | ||

| Northeast | 512473 (17.6%) | 28824 (18.8%) | |

| Midwest | 689838 (23.7%) | 42194 (27.5%) | |

| South | 1152150 (39.7%) | 54193 (35.4%) | |

| West | 550356 (18.9%) | 27969 (18.3%) | |

| Teaching Status | <0.001 | ||

| Nonteaching | 1488694 (55.5%) | 77680 (56.6%) | |

| Teaching | 1192446 (44.5%) | 59634 (43.4%) | |

| Hospitalization | |||

| Mean length of stay | 5.6 ± 7.6 | 5.4 ± 6.6 | <0.001 |

| Discharge status, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Home | 1583590 (54.6%) | 73968 (48.3%) | |

| Transfer to short-term hospital | 299378 (10.3%) | 16319 (10.7%) | |

| Transfer to facility | 356247 (12.3%) | 29135 (19.0%) | |

| Home healthcare | 230997 (8.0%) | 13840 (9.0%) | |

| Against medical advice | 19166 (0.7%) | 1252 (0.8%) | |

| Died | 410906 (14.2%) | 18420 (12.0%) | |

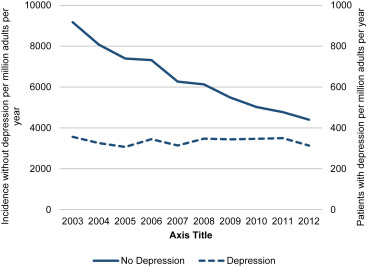

Over the study period 2003 to 2012, the incidence of STEMI in the sample decreased 51% from 9,527 to 4,715 cases per million adult years (p for trend <0.001). STEMI incidence significantly decreased 52% in patients without depression over the study period (p for trend <0.001; Figure 1 ). However, the incidence of STEMI remained stable in patients with depression (p for trend 0.74). Although the incidence of STEMI decreased 58% in women and 48% in men without depression (p for trend <0.001 in both), it remained stable in both genders with co-morbid depression (women p for trend 0.37; men p for trend 0.2).

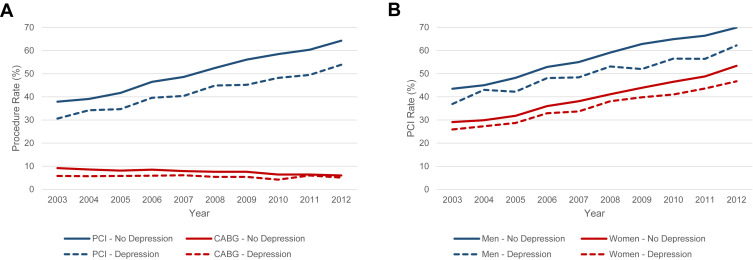

The crude rate of PCI increased 59.4% in patients without depression and 61.8% in patients with depression over the time period studied (p for trend <0.001 for all; Figure 2 ). However, the annual crude rate of PCI was consistently 5% to 10% lower in patients with depression. In additional analyses stratified by gender, PCI increased in all subgroups over the study period ( Figure 2 ; p for trend <0.001 for all). The crude rate of PCI was lower in women, and it was lowest in women with depression. In contrast, the rate of revascularization with CABG significantly decreased 30% in patients without depression over the study period (9.2% to 6.0%, p for trend <0.001). CABG rates slightly decreased in patients with depression, although the trend was not significant (5.8% to 5.1%, p for trend 0.17). Overall trends were similar in both women and men, with women having slightly lower crude rates of CABG than men regardless of the presence of depression.

In both populations with and without depression, the adjusted odds of revascularization with PCI increased annually such that patients in 2012 had >4-fold higher odds compared with those in 2003 (p for trend <0.001 for both). However, over the entire study period, depression was associated with reduced odds of revascularization with both PCI and CABG compared with those without depression ( Table 2 ). Similar results were observed in both women and men (p for interaction 0.37). In contrast to patients without cardiogenic shock, there was no association between depression and PCI in patients with cardiogenic shock (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.85 to 0.88, p <0.001 vs OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.06, p = 0.94; p for interaction <0.001). However, depression remained associated with significantly lower odds of CABG in both patients with and without cardiogenic shock (p for interaction 0.53).

| Unadjusted OR | p-Value | Adjusted OR | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | ||||

| Overall | 0.77 (0.76-0.78) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.89-0.92) | <0.001 |

| Women | 0.91 (0.90-0.93) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.86-0.90) | <0.001 |

| Men | 0.82 (0.81-0.83) | <0.001 | 0.93 (0.91-0.95) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery bypass surgery | ||||

| Overall | 0.69 (0.68-0.71) | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.74-0.78) | <0.001 |

| Women | 0.74 (0.71-0.77) | <0.001 | 0.73 (0.70-0.76) | <0.001 |

| Men | 0.77 (0.75-0.79) | <0.001 | 0.78 (0.76-0.81) | <0.001 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree