Current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for the management of patients with elevated blood cholesterol increasingly emphasize assessment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk in deciding when to initiate pharmacotherapy. The decision to treat is based primarily on mathematical integration of traditional risk factors, including age, sex, race, lipid values, systolic blood pressure, hypertension therapy, diabetes mellitus, and smoking. Advanced risk testing is selectively endorsed for patients when the decision to treat is otherwise uncertain, or more broadly interpreted as those patients who are at so-called “intermediate risk” of ASCVD events using traditional risk factors alone. These new guidelines also place new emphasis on a clinician-patient risk discussion, a process of shared decision making in which patient and physician consider the potential benefits of treatment, risk of adverse events, and patient preferences before making a final decision to initiate treatment. Advanced risk testing is likely to play an increasingly important role in this process as weaknesses in exclusive reliance on traditional risk factors are recognized, new non-statin therapies become available, and guidelines are iteratively updated. Comparative efficacy studies of the various advanced risk testing options suggest that coronary artery calcium scoring is most strongly predictive of ASCVD events. Most importantly, coronary artery calcium scoring appears to identify an important subgroup of patients with advanced subclinical atherosclerosis—who are “between” primary and secondary prevention—that might benefit from the most aggressive lipid-lowering pharmacotherapy.

In the most recent American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines on the treatment of patients’ blood cholesterol, assessment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk has been placed front and center in the selection of which primary prevention patients to treat with lipid-lowering therapy. This represents a fundamental change from prior guidelines, which also strongly weighted cholesterol levels in the algorithm for initiating treatment.

In primary prevention, statins are now recommended for patients with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentration ≥190 mg/dl, those with diabetes mellitus aged 40–75 years and have LDL-C concentrations of 70 to 189 mg/dl, and those without diabetes mellitus aged 40–75 years and who have an estimated 10-year risk of ASCVD (including heart attack and stroke) of ≥7.5%. Risk assessment is now defined by the new Pooled Cohort Equations and is based on several familiar risk factors, including age, sex, race, total cholesterol concentration, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive therapy, diabetes mellitus, and current smoking status. The decision to treat with a statin should follow a so-called clinician-patient risk discussion (CPRD), in which the risks and benefits of therapy are discussed in detail with the patient, at which time patient preferences are also taken into account.

As described in detail here, advanced risk testing is selectively endorsed to help better define risk of ASCVD for selected individual patients in whom the decision to treat is “uncertain,” making it possible to better match lipid-lowering treatment to an individual patient’s burden of atherosclerotic disease. The ACC/AHA guidelines include a class IIb recommendation for using the following factors to assess need for more aggressive therapy: LDL-C >160 mg/dl or other evidence of genetic hyperlipidemia, family history of premature ASCVD with onset <55 years in a first-degree male relative or <65 years in a first-degree female relative, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) ≥2 mg/L, abnormal coronary artery calcium (CAC) score (e.g., ≥75th percentile for age, sex, and ethnicity), ankle-brachial index (ABI) <0.9, or high lifetime risk of ASCVD.

Non-statin therapy received less attention in the new guidelines, as limited data were available at the time of guideline writing to support more widespread endorsement. In general, nonstatin therapy has been reserved for patients at the highest risk with incomplete responses to maximal dose statin therapy and/or pretreatment or on-treatment LDL-C levels suggestive of familial hyperlipidemia. However, new evidence points to a potential role for expanded use of non-statin therapies in the highest risk patients. As such, advanced risk assessment will likely take on a greater role for identifying larger groups of patients who may benefit from statins and from additional lipid-lowering therapies beyond statins.

Limitations of the Pooled Cohort Equations for Risk Assessment

The new ACC/AHA Risk Estimator is a good starting place for general risk assessment, and it represents a clear incremental improvement from prior calculators like the Framingham Risk Score. There is an excellent Web site for the new Risk Estimator ( http://tools.acc.org/ASCVD-Risk-Estimator/ ) as well as an excellent app for mobile devices. However, because of the continued reliance on patient demographic and clinical risk factors for estimation of cardiovascular risk, an emerging body of research has demonstrated that some patient subsets are at higher or lower risk than would be suggested on the basis of the ACC/AHA Risk Estimator alone.

The new ASCVD Pooled Cohort Equations were derived using pooled subject-level data from 4 prospective cohort studies conducted by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. These included the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, the Cardiovascular Health Study, the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study, and the Framingham Original and Offspring Study cohorts and encompass baseline data gathered between 1963 and 1991. The use of a more diverse data set spanning 4 cohorts has allowed the creation of separate risk assessments for white and African-American populations (The Pooled Cohort Equations), which is a great improvement over prior risk equations. However, validation studies using these new risk equations in large cohorts of contemporary patients have unexpectedly shown fair risk prediction, including in their performance in African-American patients. While diversity has been increased, not all race/ethnic groups are represented. Application of these risk estimates to patients of other racial or ethnic groups may overestimate or underestimate the true likelihood of ASCVD. For example, the risk of ASCVD may be overestimated in people of Hispanic, Chinese, or East Asian descent but could potentially be underestimated in those of South Asian ancestry.

Also notable is the fact that the risk assessment models are derived largely from study populations from a generation ago or longer, when ASCVD event rates were much higher, risk factor profiles were different, and treatment of patients with other cardiovascular risk factors was less sophisticated. As a result, the Pooled Cohort Equations may systematically overestimate the risk of contemporary patient populations (i.e., 21st century patients with contemporary risk factor exposures and medical treatments). Studies that compared the accuracy of ASCVD risk prediction using the Pooled Cohort Equations with actual event rates in modern patient cohorts found that the Pooled Cohort Equations overestimate risk of eventual ASCVD across the risk spectrum by up to 50% to 150% compared with actual observed event rates. In defense of the new guidelines, validation studies have found that overestimation of risk is greatest among those with higher risk levels (for whom treatment would already be recommended). However, overestimation of risk at lower risk levels, although less severe, could still result in initiation of statin treatment for select patients who may have less to gain.

The Pooled Cohort Equations, while helpful for most, may be insufficient to accurately predict cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in younger patients with nontraditional ASCVD risk factors, such as metabolic syndrome, obstructive sleep apnea, or chronic kidney disease, or in certain patient groups who are known to be at increased risk of atherosclerotic events including patients with lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, prior pre-eclampsia, or human immunodeficiency virus. The method of risk assessment in the Pooled Cohort Equations (i.e., the use of binomial “yes/no” assessments for variables such as current smoking status or diabetes mellitus) also may result in the loss of important information about patterns of exposure and cumulative exposure to various risk factors, which may underestimate risk for some patients.

Another potential limitation of the current guidelines is that they heavily emphasize patient age (so-called “chronological age”) in risk assessment and assignment of treatment. Calculation of ASCVD risk and initiation of statin therapy in at-risk individuals are recommended for those aged 40–75 years. However, although statin treatment is not recommended in patients >75 years, studies such as the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration and a meta-analysis of statin benefit in the elderly have demonstrated significant reductions in ASCVD event rates in older patients. In addition, chronological age is an increasingly strong principal determinant of risk in the new ASCVD prediction models. This is partly due to the inclusion of stroke in the outcome, which predominantly occurs in older patients.

In the new ACC/AHA guidelines, the definition of high CVD risk was decreased from 20% in the previous Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP-III) guidelines (which assessed coronary heart disease [CHD] only) to a 7.5% estimated 10-year ASCVD risk. With the increased importance of patient age and the decreased risk threshold for initiating treatment, many patients will exceed the 7.5% threshold entirely or almost entirely as a function of age alone. For example, the 7.5% 10-year risk threshold used in the 2013 guidelines would be met by nearly all African-American men over the age of 62, nearly all men in their mid-60s, and all women in their 70s, even in the absence of any other CVD risk factors. Among older patients, the current guidelines have high sensitivity for the detection of ASCVD risk because simply by treating so many older patients, they capture most individuals who would eventually experience ASCVD events. However, the current approach is also associated with decreased specificity (i.e., the guidelines do not screen out those patients who are unlikely to ever develop ASCVD events). It has been suggested that using higher risk thresholds to initiate statin therapy (e.g., 10% or 15% estimated risk) may improve specificity in older patients without markedly reducing sensitivity, especially in older men.

Finally, as with all prior risk factor-based models, estimates of the impact of risk factors on long-term disease outcomes are derived at the population level from large cohorts, and application to the individual patient remains problematic. Although we might expect that 10 of every 100 people with a certain combination of risk factors to have an event during a specified period of time on average, it is not necessarily the case that an “individual patient” also has a 10% risk. This would only be true if all members of the group are equally likely to experience an event. In actual clinical practice, the risk of events is influenced by many factors beyond those that are included in the risk estimation models, many of which are unknown or not easily quantified. Thus, risk estimates for individual patients remain incomplete. Indeed, many studies have shown that there are only modest relationships between a one-time measurement of clinical risk factors in adult-age and ASCVD events. A majority of ASCVD events continue to occur in patients who are considered to be at intermediate risk or lower (the so-called Rose Paradox), while many individuals with multiple risk factors never develop clinically evident disease.

When “Risk Is Uncertain”—The New Intermediate-Risk Group

Advanced risk testing has historically been considered important for the large group of patients who are at so-called “intermediate risk” for ASCVD. Under the ATP-III guidelines, intermediate risk was considered to be 10% to 20% (or 6% to 20% 10-year CHD risk), and this encompassed nearly 33% of all adults aged 40–79 years. With the recent changes in risk assessment and the new criteria for statin treatment, initial analyses of the 2013 guidelines indicated that they substantially reduced the number of people who could be at intermediate risk of ASCVD (i.e., interpreted by many as patients with estimated 10-year ASCVD risk between 5.0% and 7.4%).

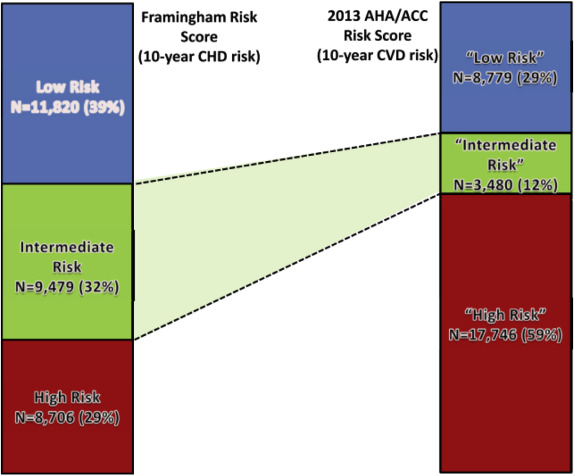

This is illustrated by a recent analysis of data from >30,000 men who were enrolled in a large multi-ethnic study of middle-aged adults and who were free of known CVD at baseline. CVD risk for this patient cohort was calculated using ATP-III definitions and the Pooled Cohort Equations established by the 2013 guidelines. Patients who were identified as intermediate risk using the new guidelines were younger (48 vs 54 years old) and were more likely to be African-American with fewer risk factors than those identified as being at intermediate risk according to the previous guidelines. Thus, the new guidelines resulted in substantial shifting of patients from intermediate to high risk: the new intermediate-risk group was only 37% of the prior ATP-III intermediate-risk group, while the size of the high-risk group more than doubled ( Figure 1 ). Nearly 80% of patients who would have been considered to be at “intermediate risk” under the previous set of guidelines are now considered to be at high risk with a more definite recommendation for statin treatment.

When “Risk Is Uncertain”—The New Intermediate-Risk Group

Advanced risk testing has historically been considered important for the large group of patients who are at so-called “intermediate risk” for ASCVD. Under the ATP-III guidelines, intermediate risk was considered to be 10% to 20% (or 6% to 20% 10-year CHD risk), and this encompassed nearly 33% of all adults aged 40–79 years. With the recent changes in risk assessment and the new criteria for statin treatment, initial analyses of the 2013 guidelines indicated that they substantially reduced the number of people who could be at intermediate risk of ASCVD (i.e., interpreted by many as patients with estimated 10-year ASCVD risk between 5.0% and 7.4%).

This is illustrated by a recent analysis of data from >30,000 men who were enrolled in a large multi-ethnic study of middle-aged adults and who were free of known CVD at baseline. CVD risk for this patient cohort was calculated using ATP-III definitions and the Pooled Cohort Equations established by the 2013 guidelines. Patients who were identified as intermediate risk using the new guidelines were younger (48 vs 54 years old) and were more likely to be African-American with fewer risk factors than those identified as being at intermediate risk according to the previous guidelines. Thus, the new guidelines resulted in substantial shifting of patients from intermediate to high risk: the new intermediate-risk group was only 37% of the prior ATP-III intermediate-risk group, while the size of the high-risk group more than doubled ( Figure 1 ). Nearly 80% of patients who would have been considered to be at “intermediate risk” under the previous set of guidelines are now considered to be at high risk with a more definite recommendation for statin treatment.

Reinterpreting Intermediate Risk Within the CPRD

However, upon re-examination by multiple experts, the interpretation of the option for advanced risk assessment “when risk or treatment is uncertain” under the new guidelines may provide clinicians even greater flexibility than before. The 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines emphasize that statin therapy should be initiated only after a CPRD, which is a dialogue between the clinician and the patient about the potential for the reduction in ASCVD events, adverse effects of treatment, drug-drug interactions, and patient preferences. Using CPRD, providers can consider advanced risk assessment in a wide variety of cases where the clinician or the patient feels uncertain about the decision to treat with lipid-lowering therapy. The 10-year risk estimate serves as a starting point for this discussion, but the final decision involves a process of shared decision making.

As per the guidelines, this discussion may include the use of other factors that modify the risk estimate, such as a family history of premature ASCVD, LDL-C ≥160 mg/dl, CAC score, hs-CRP, or ABI. Thus, a CPRD allows the clinician to adopt a testing strategy that is consistent with the patient’s preferences. Some “intermediate-risk” patients may prefer to initiate statin therapy without obtaining additional testing. For the so-called “statin-reluctant” patient, there may be a broad indication for advanced risk assessment to better understand and communicate risk.

Advanced Risk Assessment: Results of Comparative Effectiveness Studies

Understanding the true risk of CVD events is essential in making informed lipid-lowering decisions, and the new ACC/AHA guidelines rightly place the focus on treating patients most likely to receive a net benefit from therapy.

Two recent analyses of data from the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) (a prospective, population-based cohort study of 6,814 patients who were free of clinical CVD at baseline) examined the comparative effectiveness of the guideline-endorsed strategies for advanced risk assessment. In the first analysis, Yeboah et al used a recalibrated version of the Pooled Cohort Equations that were statistically corrected to ASCVD events rates observed in the MESA study to identify a group of patients not recommended for statin therapy (<7.5% 10-year ASCVD risk). They then asked which additional risk marker (LDL-C of ≥160 mg/dl; family history of ASCVD; hs-CRP of ≥2 mg/dl; CAC score of ≥300 Agatston units or ≥75th percentile for age, sex, and ethnicity; and ABI <0.9) best identified unheralded high risk that would result in reclassification to newly eligible for statin therapy. Of the tested factors, CAC scoring was the most strongly predictive of the 10-year incidence of new ASCVD events and most able to upgrade participants to a recommendation for statin therapy. CAC was followed by a family history of ASCVD. The number of patients needed to screen to identify 1 statin-eligible patient was 14.7 with CAC versus 21.8 for family history of ASCVD, 39.2 for hs-CRP, and 176 for ABI. These analyses concluded that CAC testing produced the highest yield for producing changes in treatment groups.

In the second analysis, the overall predictive accuracy of each guideline-endorsed testing strategy was calculated among those not otherwise eligible for statins. The primary statistical analysis was the calculation of the area under the receiver operating curve, or C-statistic, a measurement of how well a test (e.g., CAC score) discriminates between those who do or do not have disease. The C statistic varies from 0.5 (the test does not accurately identify those with disease) to a theoretic maximum of 1.0 (perfect discrimination). Only the CAC score, family history of ASCVD, and ABI were predictive of ASCVD events in multivariable models adjusted for the traditional risk factors. Of these, only the CAC score improved the area under the curve (C-statistic 0.76 with CAC vs 0.74 without CAC). Yeboah et al concluded that only the CAC score could lead to a significant improvement in risk discrimination beyond the recalibrated Pooled Cohort Equations.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree