Mixed cohorts of patients with ischemic and nonischemic end-stage heart failure (HF) with a QRS duration of ≥120 ms and requiring intravenous inotropes do not appear to benefit from cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT). However, CRT does provide greater benefit to patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy and might, therefore, be able to reverse the HF syndrome in such patients who are inotrope dependent. To address this question, 226 patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy who received a CRT-defibrillator and who had a left ventricular ejection fraction of ≤35% and QRS of ≥120 ms were followed up for the outcomes of death, transplantation, and ventricular assist device placement. Follow-up echocardiograms were performed in patients with ≥6 months of transplant- and ventricular assist device-free survival after CRT. The patients were divided into 3 groups: (1) never took inotropes (n = 180), (2) weaned from inotropes before CRT (n = 30), and (3) dependent on inotropes at CRT implantation (n = 16). At 47 ± 30 months of follow-up, the patients who had never taken inotropes had had the longest transplant- and ventricular assist device-free survival. The inotrope-dependent patients had the worst outcomes, and the patients weaned from inotropes experienced intermediate outcomes (p <0.0001). Reverse remodeling and left ventricular ejection fraction improvement followed a similar pattern. Among the patients weaned from and dependent on inotropes, a central venous pressure <10 mm Hg on right heart catheterization before CRT was predictive of greater left ventricular functional improvement, more profound reverse remodeling, and longer survival free of transplantation or ventricular assist device placement. In conclusion, inotrope therapy before CRT is an important marker of adverse outcomes after implantation in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy, with inotrope dependence denoting irreversible end-stage HF unresponsive to CRT.

Patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy who receive cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) experience more reverse remodeling than patients with ischemic heart disease, and reverse remodeling appears to be 1 of the most significant determinants of long-term survival in CRT recipients. It is not known whether these findings are applicable to patients with end-stage heart failure (HF) who require continuous inotrope therapy, in particular, because this population has been excluded from most clinical trials and has a poor prognosis overall. We hypothesized that patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy who require inotrope therapy might benefit from CRT, and we used data from a large, academic center registry to address this question.

Methods

The data from consecutive patients who had been implanted with CRT-defibrillators (CRT-D) from October 2002 to March 2011 at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center were analyzed in a retrospective registry. This registry included all patients with (1) left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤35%, (2) QRS duration of ≥120 ms, (3) New York Heart Association (NYHA) class 2 to 4 HF, and (4) no flow-limiting epicardial coronary artery disease, defined as ≥80% lesion in ≥1 major coronary artery, documented previous myocardial infarction with confirmatory evidence on myocardial perfusion imaging, or having undergone previous revascularization. Only those patients with a follow-up echocardiogram at ≥6 months after CRT-D or who had died, received a heart transplant, or required a ventricular assist device (VAD) before 6 months of follow-up were included. The University of Pittsburgh institutional review board approved all research.

The patients were divided into 3 groups according to their exposure to intravenous inotropes before CRT: (1) no inotropes (n = 180), (2) previous inotropes weaned before CRT-D implant (n = 30), and (3) dependent on inotropes at CRT-D implantation (n = 16). Intravenous inotropes included continuous infusions of dobutamine or milrinone. Patients underwent implantation of a CRT-D using standard transvenous techniques. High-energy leads were placed in or near the right ventricular apex, LV leads were preferentially placed within a lateral or posterolateral tributary of the coronary venous system, and right atrial leads were typically placed in the right atrial appendage. A small subgroup of patients in whom transvenous LV lead insertion was unsuccessful (n = 12) underwent surgical implantation through a minithoracotomy.

Device programming was at the discretion of the implanting physician and was altered as dictated by ongoing clinical events. Biventricular pacing was maximized by device programming, medical therapy, and/or radiofrequency ablation of the atrioventricular junction. Atrioventricular and interventricular optimization was performed in selected patients.

All patients who received inotropes were evaluated by advanced HF/transplant physicians. Attempts were made to wean patients from inotropes before CRT implantation and, if unable to do so, before hospital discharge. All inotrope-dependent patients and most patients weaned from inotropes underwent right heart catheterization to guide the medical and inotrope therapy immediately before CRT-D. Medical therapy, including β-adrenergic antagonists, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, and aldosterone antagonists, was optimized, as tolerated.

The prespecified clinical end points included death, cardiac transplantation, and the need for mechanical circulatory support with a VAD. The echocardiographic outcomes included LVEF change and left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV) change between pre-CRT echocardiography and a follow-up study ≥6 months after CRT. The LVEF change, reported in absolute percentages, was calculated as the LVEF post-CRT − LVEF pre-CRT . The LVESV change, reported in relative percentages, was calculated as [(LVESV post-CRT − LVESV pre-CRT )/LVESV pre-CRT ] × 100.

Continuous values are reported as the mean ± SD and were compared using 1-way analysis of variance with post hoc Bonferroni correction among groups or paired t testing within a group for repeated measurements. Discrete variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Time-dependent outcomes were compared using the Kaplan-Meier method and log–rank test, using a “time to first” analysis for the composite end point of death, transplantation, or VAD placement. Multivariate analysis of the time-dependent outcomes was performed using Cox proportional testing, including variables that differed at baseline, with p <0.1. Variables with significant interactions were not used together in this model. For example, the NYHA class differed significantly among the 3 groups because the inotrope-dependent patients are, by definition, in NYHA class 4 HF. The QRS pattern was not used in the model because the only difference among the groups was the proportion with nonspecific intraventricular conduction delay, which is associated with a shorter QRS duration. Receiver operating characteristic analysis was used to determine the effect of continuous variables on discrete end points. p Values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. PASW, version 18.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York) was used for all statistical tests.

Results

The data from 226 patients were analyzed. As expected, significant baseline differences were present among the 3 groups ( Table 1 ). The NYHA class increased with greater inotrope dependence, and inotrope-dependent patients were less frequently tolerant of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers and both β-adrenergic antagonists, usually because of symptomatic hypotension and/or renal dysfunction.

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 226) | No Previous Inotropes (n = 180) | Previous Inotropes (n = 30) | Inotrope-Dependent (n = 16) | p Value ⁎ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61 ± 13 | 61 ± 13 | 63 ± 14 | 57 ± 9 | 0.3 |

| Men | 122 (56%) | 97 (54%) | 19 (63%) | 11 (69%) | 0.4 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 53 (24%) | 39 (22%) | 7 (23%) | 8 (50%) | 0.04 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 96 (44%) | 74 (41%) | 21 (70%) | 7 (44%) | 0.01 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (ml/min) | 67 ± 24 | 69 ± 24 | 60 ± 18 | 64 ± 25 | 0.12 |

| New York Heart Association class | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 4 ± 0 | <0.001 † |

| Outpatient implant | 122 (54%) | 115 (64%) | 7 (23%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Electrocardiography | |||||

| QRS duration (ms) | 172 ± 32 | 176 ± 31 | 155 ± 26 | 155 ± 35 | <0.001 ‡ |

| Left bundle branch-block | 137 (61%) | 107 (59%) | 21 (70%) | 9 (56%) | 0.5 |

| Paced | 65 (29%) | 58 (29%) | 4 (13%) | 3 (19%) | 0.2 |

| Right bundle branch block or intraventricular conduction delay | 11 (5%)/13 (6%) | 10 (6%)/5 (3%) | 1 (3%)/4 (13%) | 0/4 (25%) | 0.06 |

| Left ventricular lead | |||||

| Epicardial | 12 (5%) | 9 (5%) | 3 (10%) | 0 | 0.3 |

| Anterior | 36 (16%) | 29 (16%) | 6 (20%) | 1 (6%) | 0.5 |

| Lateral | 187 (83%) | 150 (83%) | 22 (73%) | 15 (94%) | 0.2 |

| Posterior | 3 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (7%) | 0 | 0.02 |

| Medical therapy | |||||

| Intravenous inotropes before cardiac resynchronization therapy (days) | 0 | 3.8 ± 3.9 | 11.7 ± 13.2 | <0.001 | |

| β-Adrenergic antagonist | 178 (79%) | 149 (83%) | 22 (73%) | 7 (44%) | 0.001 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker | 191 (85%) | 157 (87%) | 26 (87%) | 8 (50%) | <0.001 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 41 (18%) | 35 (19%) | 4 (13%) | 2 (13%) | 0.6 |

| Digoxin | 98 (43%) | 80 (44%) | 12 (40%) | 6 (38%) | 0.8 |

| Baseline echocardiographic index | |||||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 26 ± 9 | 26 ± 9 | 23 ± 8 | 24 ± 10 | 0.10 |

| Left ventricular end-diastolic volume (ml) | 192 ± 81 | 191 ± 78 | 192 ± 77 | 216 ± 123 | 0.5 |

| Left ventricular end-systolic volume (ml) | 146 ± 73 | 144 ± 71 | 149 ± 64 | 172 ± 112 | 0.4 |

⁎ p Value reflects comparisons across the 3 inotrope groups.

† p <0.05 after Bonferroni correction for all 3 paired comparisons.

‡ p <0.05 after Bonferroni correction between inotrope-naive and other 2 groups.

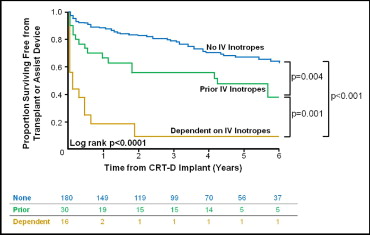

The survival data were 100% complete for a follow-up period of 47 ± 30 months. The end point of death, transplantation, or VAD occurred in 53 inotrope-naive patients (29%), 16 patients (53%) weaned from inotropes, and 14 inotrope-dependent patients (88%; p <0.001). Specifically, among patients who had never taken inotropes, 36 patients died, 15 underwent transplantation, and 2 received a VAD as a first event. Of the patients weaned from inotropes, 8 died, 6 underwent transplantation, and 2 required a VAD. In the inotrope-dependent group, 4 patients died, 6 underwent transplantation, and 4 received a VAD.

Survival free from transplantation or VAD differed significantly among the 3 cohorts (p <0.0001; Figure 1 ). Inotrope-naive patients had the best survival outcome, inotrope-dependent patients had the worst outcome, and patients weaned from inotropes experienced intermediate outcomes. The transplant- and VAD-free survival differed significantly in the pair wise univariate comparisons among the 3 groups. After correcting for a history of atrial fibrillation, the prevalence of diabetes, and QRS duration, survival free from transplantation or VAD remained highly statistically different across the groups (p <0.001). Adding β-blocker and/or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker use to the model did not affect these findings. The pair wise comparisons among the 3 groups were all statistically significant on multivariate analysis: inotrope-naive versus inotrope-dependent groups, hazard ratio (HR) 2.92 (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.13 to 4.00, p <0.001); previous inotrope use versus inotrope-dependent groups, HR 3.50 (95% CI 1.59 to 7.72, p = 0.002); and inotrope-naive and those weaned from inotropes, HR 2.25 (95% CI 1.23 to 4.12, p = 0.009). Again, adding a β-blocker and/or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker use to the model did not alter these findings.