Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC) is an acute reversible cardiac condition usually triggered by stressful events, with a predilection for older women and clinical presentation often confused with acute coronary syndrome. Definition of the diurnal hourly pattern of TTC events may contribute to understanding the pathogenesis of this complex entity. We prospectively enrolled 186 consecutive patients with TTC (68 ± 14 years old, 95% women) and, for comparison, 2,975 patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) at the Minneapolis Heart Institute over the same period. Circadian periodicity was analyzed for hourly occurrence of events throughout the day and for days of the week and months of the year. Occurrence of TTC showed a nonuniform distribution with a distinctive afternoon peak from 12:00 (noon) to 4:00 p.m. , comprising 28% (n = 52) of all events, and with the nadir at 12 to 4 a.m. (chi-square 25.6, p <0.001). Patients with events within the peak were older (73 ± 13 years) than other patients (66 ± 13 years, p = 0.0025). Events were uniformly distributed over days of the week and months (p = 0.2 and 0.47, respectively). In contrast, patients with STEMI showed peak occurrence in the early morning hours, 8:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. , comprising 24% of all events (chi-square 248, p <0.001). In conclusion, TTC events occurred in a circadian pattern with a peak in the afternoon hours, distinctive from the predilection of STEMI for morning hours. This timing of TTC events is most consistent with mechanisms underlying stressful life situations that usually trigger this condition.

Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC) is an acute cardiac condition triggered by stressful events, usually reversible, with a distinctive left ventricular (LV) contraction profile. Initial clinical presentation is often similar to an acute coronary syndrome in which events have a predilection for the early morning hours. However, whether TTC events have a particular pattern of occurrence distinctive from ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is unresolved. Such observations could potentially provide clinical clues to the pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying TTC events. To this purpose, we assessed the circadian periodicity of TTC in our large patient cohort.

Methods

From August 2001 through September 2010, 186 consecutive patients presented with TTC to the emergency and hospital facilities of the Minneapolis Heart Institute and Abbott Northwestern Hospital (Minneapolis, Minnesota). Patients shared the following diagnostic profile: (1) an acute cardiac event typically presenting with substernal chest pain; (2) systolic dysfunction with a marked regional LV contraction abnormality extending beyond the geographic territory of a single epicardial coronary artery as assessed by LV angiography, cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging, or 2-dimensional echocardiography; and (3) absence of significant obstructive atherosclerotic coronary artery stenosis (i.e., ≤50% luminal narrowing of major epicardial arteries by angiography). Patient history (obtained by the attending staff on admission) was personally reviewed and verified by S.W.S.

For comparison, we assembled 2,975 consecutively assessed patients with STEMI from obstructive atherosclerotic coronary artery disease who were treated within the level 1 acute MI program at the same institution during a similar period from March 2003 to September 2010.

For all study patients with TTC and STEMI, event onset was defined in standardized fashion as the time recorded on initial 12-lead electrocardiogram acquired on admission to the emergency department to determine if event times were consistent with circadian dependence. The day was divided into 24-hour segments and 4-hour blocks beginning at 12:00 a.m. (midnight). In addition, the week was divided into 7 days and the year into 12 calendar months. For seasonal analysis, the year was divided into 3-month periods: spring (March to May), summer (June to August), autumn (September to November), and winter (December to February).

Continuous measurements are reported as mean ± SD or median (25th, 75th percentiles) and assessed with paired or unpaired Student’s t test or Kruskal–Wallis test where appropriate. Categorical measurements were compared with standard chi-square test. Distribution of events hourly, daily, and monthly were tested for uniformity using chi-square test for goodness of fit. A nonlinear regression was performed to fit a sinusoidal curve for determining circadian variation with respect to time of events. Statistical significance was defined as a p value <0.05. All tests were analyzed with STATA 11.2 (STATA Corp., College Station, Texas). This investigation met federal regulatory requirements for exemption from institutional review board oversight and as such was granted a waiver from informed patient consent.

Results

At the time of their TTC event, patients’ ages ranged from 32 to 92 years (mean 68 ± 14); 178 were women (95%). At least 1 TTC event occurred in each of the 24 hours, most commonly at 2 to 3 p . m . (n = 17) and least frequently at 3 to 4 a . m . (n = 1).

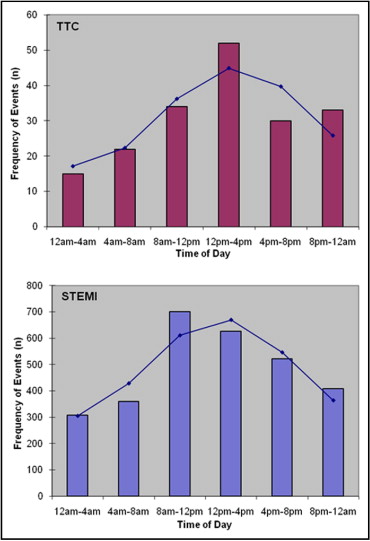

Within the TTC group a significant association was evident between time of day and event occurrence. For hourly distribution, amplitude of the sinusoidal curve was significantly different from 0 (p <0.001), consistent with circadian influence. Event times were not uniformly distributed throughout the day (chi-square 25.6, p <0.001), with a prominent peak in the early afternoon from 12 (noon) to 4 p.m. (n = 52, 28%) and the nadir from 12 (midnight) to 4 a.m. (n = 15; 8%; Figure 1 ).

Other TTC events occurred at 8 a.m. to noon (n = 34; 18%), 4 to 8 p . m . (n = 30; 16%), 8 p.m. to midnight (n = 33; 18%), and 4 to 8 a.m. (n = 22; 12%). Beta-blocker use before TTC events (38 patients, 20%) did not influence the circadian pattern of occurrence. In-hospital death occurred in 7 patients (3.8%), but with no difference evident in the circadian pattern of event onset between survivors and nonsurvivors.

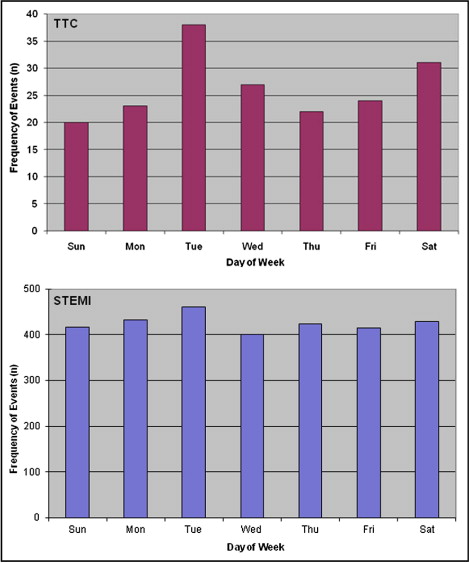

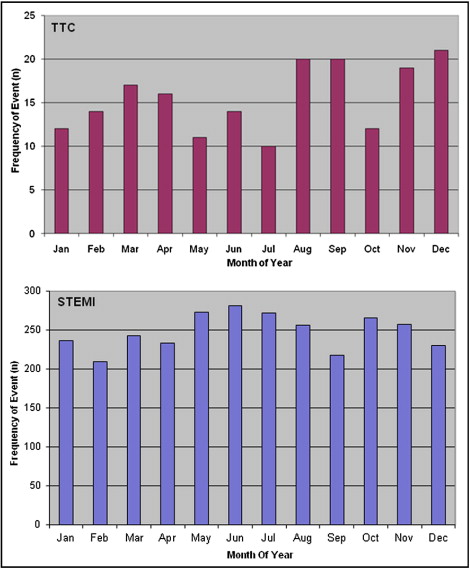

Although most common on Tuesday (n = 38, 20%) and least common on Sunday (n = 20, 14%), TTC events were uniformly distributed throughout the days of the week (chi-square 8.84, p = 0.18; Figure 2 ). Although most common in December (n = 21, 11%), TTC events were also uniformly distributed throughout the 12 calendar months (chi-square 10.7, p = 0.47) and the 4 seasons of the year (chi-square 1.14, p = 0.77; Figure 3 ).

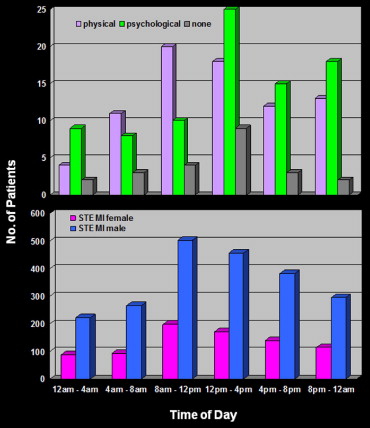

Environmental, emotional, and physical stressors could be identified in 163 of 186 patients (88%). Physical stress such as acute respiratory failure or incurred by chemotherapy for malignancy triggered TTC in 78 patients (42%); stressful emotional events such as a heated argument or grief after the death of a family member preceded TTC in 85 patients (46%).

Although physical stressors occurred most commonly in the morning at 9 to 10 a . m . (n = 9) and psychological stressors were most frequent in the afternoon at 2 to 3 p . m ., these differences in timing were not statistically significant (p = 0.26). TTC events occurring in the small subgroup (n = 23) without an identifiable stressor were also most common from noon to 4 p.m. ( Figure 4 ).

Event times did not differ in patients with TTC with versus without ST segment elevation on initial electrocardiogram (p = 0.36). A modest relation between patient age and time of event onset was evident; patients in the predilection peak from noon to 4 p.m. were older (73 ± 13 years) than all other patients (66 ± 13 years, p = 0.002).

The comparison group of 2,975 patients (63 ± 14 years old, 73% men) with atherosclerotic STEMI demonstrated a nonuniform hourly pattern of events (chi-square 248.4, p <0.001). STEMI events were distinctly different from TTC, with an early morning peak from 8 a.m. to 12 p.m. noon (n = 701, 24%) and a nadir from 12 (midnight) to 4 a.m. (n = 308, 10.5%; Figure 1 ) and was consistent with previous reports of circadian periodicity in coronary artery disease. For hourly distribution, amplitude of the sinusoidal curve was significantly different from 0 (p <0.001) consistent with circadian influence. Patient age did not vary among the 6 time intervals (p = 0.55), and no differences in event frequency were evident by gender (p = 0.96; Figure 4 ).

STEMI event occurrence by day of week was uniform (p = 0.47) and consistent with findings in patients with TTC ( Figure 2 ) but nonuniform with respect to distribution by month with a modest peak during May, June, and July (p = 0.014; Figure 3 ). Patients with TTC compared to patients with STEMI were older (68 ± 14 vs 63 ± 14 years, p <0.001), more frequently women (95% vs 27% women, p <0.001), with a lower smoking rate (35% vs 61%, p = 0.002), less frequent hyperlipidemia (36% vs 54%, p <0.001), but similar frequencies of systemic hypertension (56% vs 58%, p = 0.67) and diabetes (13% vs 17%, p = 0.13).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree