There is intense interest in examining hospital mortality in relation to gender in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. The aim of the present study was to determine whether gender influences outcomes in men and women treated with the same patency-oriented reperfusion strategy. The influence of gender on hospital mortality was tested using multivariate analysis and local regression. The influence of age was tested as a continuous and as a categorical variable. In the overall population of 2,600 consecutive patients, gender was not correlated with hospital mortality except in the subgroup of women aged ≥65 years. The risk for death increased linearly in logit scale for men. Up to the age of 65 years, the risk also increased linearly in women but thereafter increased faster than in men. Testing age as a categorical variable, hospital mortality was higher in women than in men aged ≥75 years but was similar between the genders in the younger age categories. In conclusion, despite following an equal patency-oriented management strategy in men and women with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctions, the risk for hospital death increased linearly with age but with an interaction between age and gender such that older women had an independent increase in hospital mortality. Longer time to presentation and worse baseline characteristics probably contributed to determine a high-risk subset but reinforce the need to apply, as recommended in the international guidelines in the management of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctions, the same strategy of acute reperfusion in men and women.

There is intense interest in examining gender differences in mortality after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The existing data suggest a potential interaction between age and gender, because women are on average older than men with STEMIs, and older age is strongly correlated with hospital mortality. Other factors may also contribute to apparently higher mortality in women: women are, for example, more likely to have risk factors for cardiovascular disease and to present with atypical symptoms and thus to be treated later than men. Patient and physician behavior issues may also play a role: women tend to seek less and later medical care than men, and physician management tends to be less active and less consistent with the evidence in women. Women are less likely to receive evidence-based medical care, cardiac catheterization, and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the acute phase. Contemporary registry data indicate that women with STEMI continue to have longer presentation and treatment times. Even the women who do undergo primary PCI experience worse clinical outcomes than men. At our institution, a strict policy mandating reperfusion therapy for all patients with STEMIs, regardless of gender, who present <6 hours of pain onset has been in effect for 20 years. There are no exclusions on the basis of age, although patients with advanced co-morbidities may be treated conservatively. The aim of the present study was to evaluate, in a large, single-center cohort of patients with STEMIs, the impact of gender on hospital mortality when such a “gender-blind” patency-oriented policy is implemented.

Methods

The hypothesis tested in this model was that gender is associated with differences in presentation and outcome in patients with STEMIs.

From June 1988 to December 2011, all consecutive patients admitted for STEMIs <6 hours of the onset of chest pain were included in this registry. STEMI was diagnosed on the basis of conventional criteria: chest pain lasting ≥30 minutes and resistant to treatment with nitrates, with concomitant electrocardiographic changes (≥1-mV ST-segment elevation in ≥2 limb leads or ≥2-mV elevation in ≥2 contiguous precordial leads) and eventually confirmed by elevation of creatine kinase to >2 times the upper limit of normal. Reperfusion therapy was provided to all patients according to a previously described patency-oriented strategy. Briefly, (1) primary PCI was performed in patients presenting directly to our institution and to patients transferred from other institutions or the prehospital setting with either contraindications to fibrinolysis or lack of receipt of thrombolysis, (2) patients who had received prehospital intravenous fibrinolysis routinely underwent coronary angiography 60 to 90 minutes after lytic administration to ascertain the patency of the infarct-related artery, and rescue angioplasty was performed immediately if the Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow grade was <3 in the infarct artery, and (3) conservative medical therapy was restricted to patients with major advanced co-morbid factors, limited life expectancies, or contraindications to fibrinolysis and invasive therapy.

Modalities of admission were divided into 2 categories: those who called first the emergency medical service (EMS) and those with other admission modalities (transfer from another hospital, hospital acute myocardial infarction, or first admission to the emergency department). The perfusion status of the infarct-related artery was determined in accordance with the TIMI classification, and all coronary angiograms were reviewed by 2 angiographers. Successful reperfusion was defined as TIMI flow grade 3 in the infarct-related artery. Multivessel disease was defined as the presence of ≥50% diameter stenosis in ≥2 major epicardial arteries. Cardiogenic shock on admission was defined as the combination of systolic blood pressure ≤80 mm Hg despite volume expansion and treatment with inotropic drugs, signs of acute circulatory failure (cyanosis, cold extremities, restlessness, mental confusion, or coma), and congestive heart failure.

Hospital death included deaths due to cardiac or noncardiac causes.

Descriptive statistics are expressed as percentages for qualitative variables and as mean ± SD for quantitative variables. The analysis was divided into 2 parts. First, the population was divided into 4 groups according to gender (male or female) and age (<65 or ≥65 years), and comparisons between the genders were performed in the 2 age classes. Qualitative variables were compared using chi-square tests and quantitative variables using Student’s t tests. The second part of the analysis aimed to find a risk function for hospital mortality, with particular emphasis on the effects of age and gender. This analysis involved 2 steps. First, a univariate analysis was performed to select prognostic factors to be included in the second step. All categorical variables were tested using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests: risk factors for coronary artery disease, location of myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock on admission, modality of admission, ventricular fibrillation before admission, previous cardiovascular events (PCI, myocardial infarction, or coronary artery bypass surgery), multivessel coronary disease, initial and final TIMI flow grade 3 in the infarct-related artery, use of stents, and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor treatment. Continuous variables were time to admission, time from pain onset to fibrinolysis, and final time from onset of pain to achievement of TIMI flow grade 3. The relations among age, gender, and hospital mortality were analyzed as follows: age was divided into 5-year intervals, and logits of death proportions were computed for each age class and for both genders. Local regression (LOESS) was performed with death proportion logit as the dependent variable and age class as the independent variable, for both genders. LOESS is a nonparametric regression method that allows visualization of the shape of the regression function of a variable with respect to another variable. This coding was able to suggest change points of the log odds ratio of hospital mortality according to age in both genders and eventually to define 6 dummy variables: age, age for women, age if age ≥65 years, age if age ≥65 years and female, age if age ≥75 years, and age if age ≥75 years and female. This procedure is a method for coding an age-gender interaction in a more precise way than the usual product of age and gender. A stepwise logistic regression was performed in a second step. Note that age was coded using 5-year classes for LOESS but as a continuous variable in the logistic regression analysis. Variables included were those that were significant with p values <0.10 in the univariate analysis and the 6 dummy variables coding for age and gender issued from LOESS. Variables retained in the final model were those with p values <0.05 by the Wald test. All tests were 2 tailed, and p values <0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

From June 1988 to December 2011, 2,600 consecutive patients were admitted 6 hours after the onset of symptoms and had final diagnoses of STEMI. The baseline characteristics of the patients and the use of reperfusion therapy, according to age group and gender, are listed in Table 1 . The baseline characteristics of younger men and women (aged <65 years) were quite similar, except for a higher rate of active smoking in men. Women were admitted to the hospital on average slightly later than men. The frequency of cardiogenic shock on admission was similar, but ventricular fibrillation before admission was twice as frequent in younger women compared with younger men. History of previous myocardial infarction or PCI was more frequent in men, and they had a higher rate of multivessel disease. The same proportion of men and women (>50%) called EMS first in the 2 groups.

| Variable | Age <65 yrs | Age ≥65 yrs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (n = 199) | Men (n = 1,566) | p Value | Women (n = 268) | Men (n = 567) | p Value | |

| Age (yrs) | 51.1 ± 8.8 | 51.2 ± 8.2 | 0.94 | 77 ± 7 | 73 ± 6 | 0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 31% | 26% | 0.18 | 66% | 48% | 0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 15% | 12% | 0.24 | 16% | 18% | 0.54 |

| Dyslipidemia | 33% | 38% | 0.12 | 40% | 45% | 0.16 |

| Family history of coronary artery disease | 36% | 32% | 0.34 | 20% | 18% | 0.56 |

| Current smokers | 60% | 76% | 0.001 | 20% | 43% | 0.0001 |

| Time from pain onset to admission (minutes) | 188 ± 85 | 176 ± 84 | 0.05 | 208 ± 159 | 180 ± 81 | 0.0008 |

| First call to EMS | 58% | 65% | 0.07 | 66% | 71% | 0.18 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 5% | 4.5% | 0.72 | 9% | 8% | 0.69 |

| Ventricular fibrillation before admission | 11% | 6% | 0.01 | 4% | 7% | 0.13 |

| Anterior wall location | 45% | 45% | 0.94 | 43% | 51% | 0.003 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 2.5% | 9.5% | 0.001 | 7% | 14% | 0.003 |

| Previous PCI | 2% | 8% | 0.003 | 4% | 11% | 0.002 |

| Contraindication to thrombolytic therapy | 18% | 15% | 0.22 | 20% | 20% | 0.81 |

| Initial TIMI flow grade 3 | 32% | 33% | 0.92 | 25% | 29% | 0.59 |

| Multivessel coronary disease | 27% | 40% | 0.0003 | 61% | 58% | 0.50 |

| Reperfusion therapy modalities | ||||||

| Primary PCI | 62% | 65% | 0.50 | 67% | 68% | 0.73 |

| Stents | 52% | 56% | 0.33 | 47% | 48% | 0.74 |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor | 34% | 36% | 0.45 | 21% | 34% | 0.0004 |

| Fibrinolysis | 27% | 30% | 0.42 | 20% | 23% | 0.43 |

| Time from pain onset to thrombolytic therapy (minutes) | 147 ± 73 | 153 ± 71 | 0.52 | 201 ± 95 | 168 ± 77 | 0.01 |

| Final TIMI grade 3 flow | 89% | 91% | 0.39 | 80% | 82% | 0.80 |

| Time from pain onset to reperfusion (minutes) | 241 ± 91 | 231 ± 90 | 0.06 | 261 ± 102 | 235 ± 95 | 0.001 |

With respect to older patients (aged ≥65 years), baseline characteristics differed greatly. Women were on average still older than men (77 vs 73 years, respectively, p <0.0001). The rate of current smoking was lower in women, and women were more frequently treated for hypertension. Time from pain onset to admission was markedly longer for elderly women. Anterior myocardial infarction location was more frequent in men as well as previous myocardial infarction and coronary angioplasty, but the rate of multivessel disease was similar between the genders. The same proportion of patients (>50%) called EMS first in the 2 groups.

In patients aged <65 years, the distribution of reperfusion therapy did not differ according to gender (89% in women [PCI 62%, fibrinolysis 27%] vs 95% in men [PCI 65%, fibrinolysis 30%]), with similar rates of use of stents and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors ( Table 1 ). Similar findings were observed in older patients: 87% of women received reperfusion therapy (PCI 67%, fibrinolysis 20%) compared with 91% in men (PCI 68%, fibrinolysis 23%). The number of stents implanted was similar, but a higher rate of use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors was observed in elderly men.

In the acute phase, angiographically confirmed final TIMI grade 3 flow in the infarct-related artery was obtained in 89% of younger women compared with 91% of younger men. There was no difference in the mean time interval from the onset of chest pain to final TIMI grade 3 flow. Among the older patients, the rates of TIMI flow grade 3 were quite similar between women and men, but the mean delay from the onset of chest pain to final TIMI flow grade 3 was substantially longer in women.

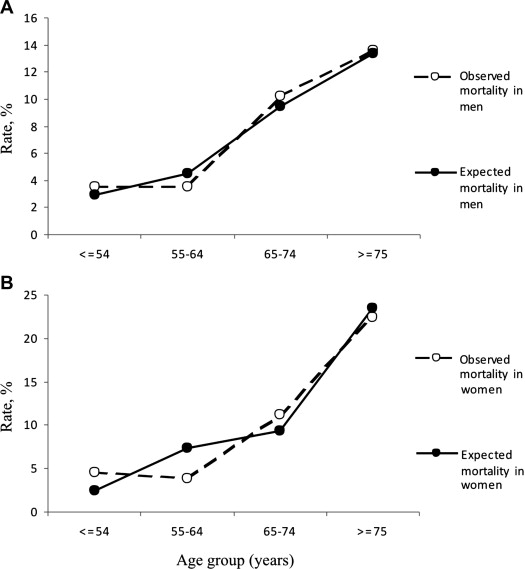

Observed and expected mortality rates for men and women are displayed by age category in Figure 1 . Observed mortality rates were similar for men and women up to 74 years of age, but in patients aged ≥75 years, the observed mortality rate was higher in women than in men (22% vs 14%, p = 0.03).

Factors correlated with hospital death on multivariate analysis are listed in Table 2 . Age but not gender was correlated with hospital death, and after testing the 6 previously described dummy variables, only age if age ≥65 years and female (per 10-year increase) was correlated with hospital mortality. Other factors correlated with hospital mortality included cardiogenic shock at admission, multivessel disease, anterior myocardial infarction, and ventricular fibrillation before admission. Three factors were associated with better survival: active smoking, dyslipidemia, and final TIMI flow grade 3.