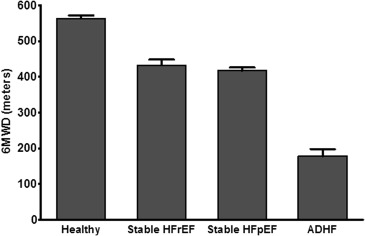

Older patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) have persistently poor outcomes including frequent rehospitalization despite guidelines-based therapy. We hypothesized that such patients have multiple, severe impairments in physical function, cognition, and mood that are not addressed by current care pathways. We prospectively examined frailty, physical function, cognition, mood, and quality of life in 27 consecutive older patients with ADHF at 3 medical centers and compared these with 197 participants in 3 age-matched cohorts: stable heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (n = 80), stable HF with reduced ejection fraction (n = 56), and healthy older adults (n = 61). Based on Fried criteria, frailty was present in 56% of patients with ADHF versus 0 for the age-matched chronic HF and health cohorts. Patients with ADHF had markedly reduced Short Physical Performance Battery score (5.3 ± 2.8) and 6-minute walk distance (178 ± 102 m) (p <0.001 vs other cohorts), with severe deficits in all domains of physical function: balance, mobility, strength, and endurance. In the patients with ADHF, cognitive impairment (78%) and depression (30%) were common, and quality of life was poor. In conclusion, older patients with ADHF are frequently frail with severe and widespread impairments in physical function, cognition, mood, and quality of life that may contribute to their persistently poor outcomes, are frequently unrecognized, are not addressed in current ADHF care paradigms, and are potentially modifiable with targeted interventions.

After a hospitalization for acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF), older patients have high rates of morbidity, including frequent rehospitalization, mortality, and health care expenditures, and these remain high even with adherence to guidelines-based heart failure (HF)–specific management strategies. Importantly, these patients typically have multiple co-morbidities, and subsequent adverse events are frequently because of noncardiac causes. The development of ADHF and the physiological stressors associated with the hospital environment may accelerate functional decrease and frailty already present because of aging, chronic HF, and multimorbidity, exacerbate impairments in cognition and mood, and lead to further declines in quality of life. These impairments are associated with poor outcomes and may be modifiable with targeted interventions. However, current ADHF management strategies rarely address frailty and associated impairments in physical function, cognition, or mood. A comprehensive examination of these impairments could help guide investigations of novel assessments and interventions for older patients with ADHF. The purpose of this prospective study was to comprehensively assess impairments in older patients hospitalized with ADHF using standardized assessments of frailty, physical function, cognition, mood, and quality of life and compare key measures of physical function and frailty to age-matched cohorts of stable patients with HF and healthy older adults.

Methods

We conducted a prospective, comprehensive, multidimensional assessment of 27 patients ≥60 years hospitalized with ADHF and compared their performance in key measures to 3 age-matched cohorts previously enrolled as outpatients: (1) stable HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) (n = 80), (2) stable HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) (n = 56), and (3) healthy older adults (n = 61).

The ADHF cohort was recruited at 3 academic medical centers (Wake Forest Medical, Duke University and Thomas Jefferson University). The diagnosis of ADHF was based on prespecified criteria (symptoms, signs, clinical tests, and response to medical therapy) and confirmed by a study HF cardiologist. Participants had to have been independent with basic activities of daily living before hospitalization and ambulatory (assistive device allowed) with discharge planned to home at the time of enrollment.

As previously described, chronic stable patients with HF with either preserved (≥50%) or reduced (≤35%) left ventricular ejection fraction were recruited from Wake Forest Medical Center using the validated Rich et al and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey HF criteria. These participants had no recent hospitalizations or medical condition that could mimic HF.

The age-matched healthy cohort was recruited from the community, excluding those with any chronic medical illness or chronic medication prescription. All participants provided informed consent, and the study was approved by the institutional review boards at each center.

Trained personnel using standardized protocols performed all study measures. In the ADHF cohort, assessments were collected during hospitalization after successful initial treatment for ADHF and an average of 1 day before hospital discharge. Identical measures were collected in the age-matched chronic stable patients with HFpEF and healthy older adults at pre-scheduled study visits. Assessment in the chronic stable HFrEF cohort was limited to 6-minute walk distance (6MWD).

Frailty was based on meeting at least 3 of 5 previously validated cutoffs for the domains described by Fried et al : slowness, weakness, weight loss, exhaustion, and low physical activity. Additional definitions of this key outcome included: Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) score <6, gait speed <0.8 m/s, and handgrip strength <30 kg in men and <20 kg in women.

Physical function was assessed by 6MWD, the SPPB, and handgrip strength. The 6MWD was collected in an unobstructed corridor according to recommended guidelines. The SPPB includes 3 components, standing balance, gait speed over 4 m, and time to complete repeated chair rise. Each component is scored from 0 to 4 and summed for a total score of 0 to 12. Handgrip strength was based on the better of 2 measures in the dominant (stronger) hand using a hand dynamometer with the participant seated and elbow flexed to 90°. Cognitive function and depression were assessed using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale, respectively. The Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire was used to assess quality of life. Medical history, including clinical history of depression or cognitive impairment, and demographic information were obtained through chart review and patient interview.

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD or median and interquartile range and categorical variables as number and percentage. Comparisons between age-matched cohorts were made using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and analysis of covariance for continuous variables, adjusting for age and ejection fraction and with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons when appropriate. Among patients with ADHF, comparisons of measures between HFrEF and HFpEF were made by an independent-samples t test for continuous variables and by Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. A 2-tailed p value <0.05 was required for significance.

Results

Participant age was similar across all cohorts ( Table 1 ). Women were more common in HFpEF (80%) and less common in HFrEF (34%) compared with the ADHF (59%), which included a mix of patients with HFpEF and HFrEF, and healthy cohorts (62%) (p <0.05 for each comparison). The ADHF cohort was more racially diverse ( Table 1 ).

| Characteristics | ADHF (N=27) | Stable HFpEF (N=80) | Stable HFrEF (N=56) | Healthy (N=61) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 72 ± 10 | 71 ± 7 | 69 ± 5 | 69 ± 7 |

| Women | 59% † | 80% | 34% | 62% |

| Black | 56% ∗ | 29% | 18% | 5% |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 29.3±6.7 ∗ | 31.9±6.5 | 26.6±4.3 | 25.9±4.9 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 37±16 ∗ | 62±7 | 32±10 | 66±7 |

| Hypertension | 89% ‡ | 88% | 52% | N/A |

| Diabetes mellitus | 48% § | 23% | 27% | N/A |

| Ischemic heart disease | 63% † | 0% | 25% | N/A |

| Diuretic | 100% † | 73% | 82% | N/A |

| Beta-blocker | 85% † | 31% | 11% | N/A |

| Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor or Angiotensin II receptor blocker | 59% | 53% | 79% | N/A |

| Digoxin | 7% ‡ | 1% | 71% | N/A |

∗ ADHF is significantly different than HFREF and HFPEF.

† ADHF is significantly different from all 3 groups.

‡ ADHF is significantly different than HFREF.

§ ADHF is significantly different than HFPEF. Comparisons made using analysis of variance for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

Frailty was common (>50%) in ADHF participants by multiple criteria but was rare or absent in other cohorts (0% to 14% depending on the cohort and criteria applied; Table 2 ).

| ADHF | Stable HFpEF | Healthy | ADHF vs HFpEF; p-value | ADHF vs Healthy; p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frailty Phenotype | |||||

| Frail (≥ 3 of 5 domains met) | 56% | 0 | 0 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Pre-frail (1-2 domains met) | 41% | 58% | 10% | 0.30 | <0.001 |

| Frailty domains | |||||

| Slowness (gait speed) | 74% | 4% | 0 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Weakness (handgrip) | 56% | 11% | 8% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Weight loss | 0 | 0 | 2% | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Exhaustion | 85% | 33% | 0 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Low physical activity | 33% | 25% | 0 | 0.84 | <0.001 |

| Additional Frailty Criteria | |||||

| Short Physical Performance Battery score < 6 | 56% | 0 | 0 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Gait speed < 0.8 m/s | 81% | 14% | 0 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Handgrip strength men <30 kg; women <20 kg | 48% | 9% | 3% | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Physical Function | |||||

| Short Physical Performance Battery components | |||||

| Chair rise score | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.9 ∗ | 3.3 ± 0.7 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Balance score | 2.4 ± 1.4 | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Gait speed score | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.0 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 0.58 ± 0.23 | 0.98 ± 0.21 ∗ | 1.22 ± 0.17 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Handgrip strength (kg) | |||||

| Men | 30.3 ± 11.3 | 46.1 ± 8.0 | 52.4 ± 10.3 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Women | 20.7 ± 6.1 | 28.9 ± 9.4 | 27.6 ± 6.9 | < 0.01 | < 0.04 |

∗ Chronic, stable HFpEF significantly different compared to Healthy (p <0.01). Data presented as mean ± standard deviation or percentage. For continuous variables, p-value is from analysis of covariance, with age and ejection fraction as covariates. For categorical variables, p-value is from Fisher’s exact test. Bonferroni correction used for multiple comparisons.

Older patients with ADHF had severe reductions in all domains of physical function: balance, mobility (gait speed), strength, and endurance ( Table 2 ; Figures 1 and 2 ). Average 6MWD, SPPB score, and gait speed were ∼50% lower in ADHF than in stable HF or healthy older adults. Balance deficits were unexpectedly common, with most ADHF participants unable to attempt (33%) or maintain (56%) tandem stance for even 3 seconds (normal is ≥10 seconds). Lower extremity strength (chair rise performance) was especially impaired, with 41% of ADHF participants lacking the leg strength to stand from a seated position without using arms even once. Weakness appeared generalized as handgrip strength was also significantly reduced in ADHF. Functional impairments in chronic stable HF cohorts were less severe and less generalized than in ADHF but were greater than in healthy age-matched participants. Thus, there was a steep gradient of impairments from healthy older adults to chronic HF to ADHF.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree