Cigarette Smoking and Smoking Cessation

GENERAL BACKGROUND

Native Americans discovered the use of the tobacco plant, Nicotiana tabacum, during antiquity. By the time Columbus arrived in America, tobacco use was widespread throughout the Western Hemisphere and was well integrated into Native American cultures. Production of tobacco and its trade represented a major economic activity in the pre-Columbian Americas. Early European explorers learned of the tobacco plant from Native Americans, and by the mid-17th century tobacco was widely used in Europe.

The most important, but not the only, active psychopharmaceutical drug contained in the leaves of the tobacco plant is nicotine.1,2 Nicotine is a major metabolic product of the tobacco plant, and it is likely that it evolved as a protection against insect predators, as nicotine is a potent insect neurotoxin.3 Interestingly, nicotine has been exploited in this regard as a commercial insecticide. Nicotine, however, is the major addicting substance in tobacco, although the addiction to tobacco is more complex than addiction to nicotine alone. Other psychoactive compounds are also present in tobacco smoke, including monoamine oxidase inhibitors.4 These may have either direct effects or interact with other psychoactive drugs.1,2 In addition, conditioned behavior and social interactions are important drivers of smoking.5–8

Nicotine is a potent euphoriant. On a molar basis, nicotine is more active than such euphoria-inducing drugs as cocaine, amphetamine, or morphine.9 Nicotine elicits complex effects on the central nervous system (CNS), which are discussed in more detail below. Many of these effects, however, are perceived as desirable, accounting for the popularity of smoking. For example, nicotine ameliorates anxiety, reduces perception of pain,10 mitigates symptoms of depression,11 and induces a sense of well-being9 while causing a state of arousal.12 In contrast to many euphoriants that impair cognition, nicotine can improve task performance and attention time by measurable degrees in nonhabituated individuals and may have beneficial effects on cognition.12

Despite its perceived benefits, smoking of tobacco has long been controversial. King James of England wrote in 1604 “[Smoking is] a custom loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, dangerous to the lungs, and in the black stinking fume thereof, nearest resembling the horrible Stygian smoke of the pit that is bottomless.13” The Surgeon General’s Report of 1964 outlined the convincing evidence for the health consequences of smoking.14 Since that time there has been a gradual increase in efforts to control tobacco use and the associated health consequences. Changes in social attitude, public health efforts, and both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches have been developed that have meaningful benefits. The current chapter will focus on treatment designed to help a smoker achieve abstinence.

NICOTINE ADDICTION

Nicotine exerts its biologic effects on “nicotinic” receptors, a subset of cholinergic receptors, whose endogenous ligand is acetylcholine.15,16 Nicotinic receptors are homo- or heteropentamers that bind two ligand molecules and form an ion channel.17 In man, 17 genes code for distinct component chains, resulting in a very large number of potential pentamers, although only a relatively few are believed to have a biologic role. In the brain, nine alpha and three beta receptors are expressed. However the major receptors are composed of complexes (alpha4)(beta2), (alpha3)(beta4), and (alpha7). The (alpha4)(beta2) complex incorporates other subunits, particularly (alpha5), (alpha6), or (beta3), and these may modulate the effects of ligands, including nicotine.17 The (alpha4)3(beta2)2 receptor is believed to be particularly important in the addicting effects of nicotine. Deleting the (beta2) receptor in mice eliminates behavioral responses to nicotine, while mutations in the gene can result in markedly increased sensitivity to nicotine.18 The (alpha7)5 receptor, for example, is believed to mediate some of the cognitive effects of nicotine, including sensory gating and learning.18,19 In contrast the muscarinic receptors, the other major class of cholinergic receptors, are single chain G-protein–coupled receptors. Nicotine has no effect on these receptors.

Nicotinic receptors are ion channels and upon binding of nicotine, permeability of the channel is increased.15–18 For example, binding of nicotine to the (alpha4)3(beta2)2 allows influx of calcium. This, in turn, modulates release of neurotransmitters. It is likely that the behavioral responses to nicotine result from the actions of many neurotransmitters, but dopamine is believed to be a major mediator of nicotine effects. In this context, dopamine is a key mediator of pleasure and reward and is required for the reinforcing effects that lead to drug self-administration in animal models.20 As such, dopaminergic signaling is believed to be key in the pathogenesis of many addictions and compulsive behaviors. Nicotine also modulates the release of other neurotransmitters, including glutamate and gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA). Interestingly, chronic administration of nicotine desensitizes neurons that release GABA, which inhibits dopamine release. In contrast, there is no desensitization of glutamate release, which augments dopamine release. Chronic nicotine exposure, therefore, can lead to further augmentation, nicotine-induced dopamine release.21,22 Moreover, the CNS alterations that occur following nicotine administration can be very long lasting; for example, alterations in nicotine receptor levels in rats exposed in utero persist until adult life.23 The adolescent brain may be particularly sensitive to long-term alterations induced by nicotine.24 This may account for the sensitivity of adolescents to addiction. Persistent changes in the brain may also account for the observation that, even after achieving abstinence, a smoker is at risk for relapse and if relapse occurs, the smoker reverts to the previous “steady-state” habit much more rapidly than that habit developed initially.

Nicotine is contained in the leaves of the tobacco plant. Nicotine is a weak base and as a result will be charged in acidic environments. Many forms of tobacco, such as cigars and chewing tobacco, are alkalinized, which results in uncharged nicotine that can be more readily absorbed through the buccal mucosa. Thus, cigar smokers do not have to inhale to achieve desired blood nicotine levels. The process of smoking a cigarette is more complex.25 Air sucked through the burning end of a cigarette becomes heated. As the hot air passes down the bole of a cigarette, it causes the nicotine in the tobacco to volatilize. As the mixture cools, the nicotine condenses on smoke particles resulting in a nicotine aerosol. Conventional cigarettes have been designed so that the resulting particle size is ideal to reach the alveolar structures of the lung. Uncharged nicotine is lipid soluble and is rapidly absorbed from the alveolar gas into the pulmonary capillary blood and then into the arterial circulation. Inhaled nicotine, therefore, reaches the brain in about ½ a circulation time or about 15 to 20 seconds. In its neutral form, nicotine readily crosses the blood–brain barrier and exerts its psychoactive effects. A cigarette, therefore, is a very effective means of delivering nicotine to the brain. It also allows a smoker to control the dose of delivered drug with considerable precision.

After absorption, nicotine distributes into various body pools. This results in a marked difference between arterial and venous nicotine levels and a rapid drop in nicotine levels upon completion of a cigarette.26 Nicotine is then catabolized by several enzymes. The most important of these is CYP2A6 which oxidizes nicotine to cotinine and cotinine to hydroxycotinine.27 Nicotine can also be oxidized by alternative CYP450 enzymes and may be inactivated and excreted by glucuronidation. Genetic variants in nicotine metabolizing enzymes can influence smoking behavior. In normal metabolizers, nicotine is cleared with a half-life of about 2 hours. As a result, nicotine levels increase throughout the day for individuals who smoke steadily. The increase in nicotine levels can result in levels believed to fully saturate all nicotinic receptors.1,2 In this setting, it is likely that smoking behavior is more dependent on conditioned responses than on psychopharmacologic effects of nicotine. Conversely, nicotine levels fall at night. The drop in nicotine levels is thought to initiate the early stages of withdrawal. Importantly, the lower levels allow for nicotinic receptors to be in the unbound state. As a result, the first cigarette in the morning can have a large psychodynamic effect. This is well recognized by smokers who will often report that the “most enjoyable” cigarette is the first one smoked in the morning. In addition, the drop in nicotine levels is thought to initiate the early stages of withdrawal. How long it takes a smoker to smoke the first cigarette of the day, therefore, serves as a gauge of addiction, with short times indicating stronger addiction. Smoking within 30 minutes of awakening is a key question in the Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence.28

Several lines of evidence support genetic influences on smoking behavior.29–32 Twin studies suggest that genetics accounts for about 50% of the variance in smoking. Interestingly, there appears to be a genetic basis for withdrawal symptoms.33 A number of genes have been suggested to play a role in both candidate gene and in genome-wide association studies. Although many of the candidate genes have been difficult to reproduce, an extremely strong signal has been consistently observed in a region of chromosome 15 that includes the genes for three nicotinic receptors.34 Among COPD patients, this region is also associated with intensity of smoking assessed by cigarettes smoked per day, suggesting it may be related to intensity of addiction.35 As might be expected of a gene related to smoking behavior, this region has also been strongly linked to the risk for several smoking-related diseases.36–39 Candidate genes include not only genes in the dopamine pathway, but also other neurotransmitter pathways as well as cell adhesion molecules that are thought to contribute to long-term memory and neural adaptation.

Genetic variation in nicotine metabolizing enzymes has received particular attention.31 Many, but not all studies have demonstrated that individuals with variants in CYP2A6 who metabolize nicotine slowly smoke fewer cigarettes and maintain lower cotinine and carbon monoxide levels consistent with their requiring less total intake.35,40,41 Consistent with a reduced level of smoking, some studies have shown reduced risk for cancer in slow metabolizers.42,43 Similarly, better lung function has been reported among individuals with haplotypes associated with slow metabolism compared to those with genes associated with rapid metabolism who smoke the same number of cigarettes.44

It is plausible that the slower decline in blood nicotine levels associated with slow nicotine metabolism makes these individuals less likely to experience withdrawal. In addition, the persistence of nicotine may decrease the “reward” of smoking. Both of these effects may contribute to increased likelihood that a slow metabolizer can achieve abstinence from smoking40 and better quit rates have been observed among slow metabolizers in clinical trials.31,45 On the other hand, slow metabolizers who are experimenting with smoking may have higher and more sustained nicotine levels. Consistent with this, a prospective study of adolescents observed a threefold risk of becoming a regular smoker among slow metabolizers.46

Smoking cigarettes is more complex than nicotine addiction. Conditioned behaviors also play a key role.1,2 In this context, a smoker typically inhales 10 puffs per cigarette. This would be 300 puffs for a 1½ pack per day smoker or more than 100,000 puffs annually. In addition, smoking frequently occurs in recurrent settings: after eating, when irritated, when bored, when sad, in specific social settings, etc. As such, smoking becomes associated with these settings which serve as operant cues to induce smoking behavior. Nicotine, moreover, has been demonstrated to increase both the intensity of operant conditioning as well as its persistence.6,47 The development of addiction to tobacco, therefore, involves not only development of addiction to nicotine, but also acquisition of conditioned behaviors, which nicotine facilitates. Because these cue-mediated behaviors can be very persistent, they are major causes of relapse.

Tobacco addiction most commonly begins in late childhood or adolescence,48–51 although smoking can begin in young adulthood.52,53 Historically, in the United States, the peak incidence for developing a regular tobacco habit is in adolescence. Individuals who do not acquire a habit prior to age 20 were unlikely to do so as adults.48 The demographics of smoking initiation were well known to the tobacco industry. Marketing campaigns designed to promote the image of specific brands of cigarettes were carefully designed and were exceedingly effective in leading to logo recognition among children as young as kindergartners51,54 and contributed to brand selection among American adolescents. The susceptibility of children to these campaigns was a major driver in leading to the current ban on tobacco advertising in media likely to be seen by children. Importantly, since most exploratory smoking occurs in peer-related social settings, the social context of smoking is a crucial variable in determining smoking initiation.51,55,56

Most children who begin to smoke do so on an occasional basis. Within a few years, however, a regular habit may develop. Most often this habit is characterized by smoking only a few cigarettes daily. As noted above, slow metabolizers may be particularly susceptible to addiction due to higher nicotine levels and longer persistence.46 The number of cigarettes smoked, however, generally increases for the first 8 to 10 years. Important variations on this pattern exist, suggesting biologic differences among smokers. Some smokers achieve a “mature addiction” very rapidly. In contrast, as many as 15% of smokers, termed “chippers,” may continue to smoke episodically and may not be fully addicted.57,58

Smoking is more common among those with psychiatric disorders.59–61 This includes individuals with depression, anxiety disorders, and cognitive disorders such as schizophrenia as well as other drug dependencies. The basis for this relationship is unclear. Nicotine has modest antidepressant and antianxiety effects, and the suggestion has been made that some individuals with mood disorders may smoke to “auto-medicate.” Alternatively, it has been suggested that smoking and psychiatric disorders may share common genetic risk factors. Another possibility is that smoking early in life may lead to alterations in the CNS that may lead, in turn, to psychiatric disorders. In support of this, smoking more commonly precedes first psychotic episodes.61 Whatever the mechanisms, the concurrent presence of psychiatric disorders can complicate efforts to achieve smoking abstinence.

Once a smoker achieves a “mature” addiction, cigarette consumption typically remains very constant. Interestingly, the smoker appears to adjust both nicotine intake and number of cigarettes smoked independently. If supplemental nicotine is administered, smokers will often reduce their nicotine consumption.62 Alternatively, if smoking is restricted, for example, by decreasing the number of cigarettes available, smokers will alter their smoking strategy, for example, by smoking each cigarette more deeply, to maintain a relatively constant nicotine intake.63 Similarly, acidification of the urine increases while alkalinization slows nicotine clearance, and there are corresponding increases and decreases in nicotine intake that are achieved with no change in the number of cigarettes smoked.64 Rather, smokers alter the way in which individual cigarettes are smoked, that is, the depth and duration of inhalation and the number of puffs, thus modifying the nicotine absorbed. Consistent with self-regulation of nicotine administration, low–nicotine-content cigarettes do not result in lower nicotine consumption.65 This illustrates the complexity of smoking where both nicotine addiction and conditioned behaviors contribute.

While the pathogenetic mechanisms underlying withdrawal symptoms are incompletely understood, it is generally believed that some withdrawal symptoms are related to decreases in nicotine blood levels below certain thresholds. Variations in nicotine metabolism would be expected to affect the timing of symptom onset. Some smokers, for example, may experience nicotine withdrawal at night when sleep interferes with nicotine intake.66 The concept that nicotine replacement can help ameliorate withdrawal symptoms by maintaining nicotine blood levels is also an important concept underlying nicotine replacement as an aid to smoking cessation. In addition, susceptibility to specific symptoms may be genetically determined.67,68

SMOKING AS A PUBLIC HEALTH PROBLEM

Cigarette smoking is a major public health problem and is perhaps the most important cause of preventable disease. The number of deaths attributed to cigarette smoking in the United States has been estimated to be well in excess of 400,000 annually and has been for many years.69,70 This exceeds deaths attributed to other specific causes.71 The health burden attributable to smoking parallels smoking prevalence. As a result, smoking-induced disease is becoming more common in the developing world where smoking prevalence has been increasing, particularly in specific subpopulations such as young and middle-aged males.72 In the United States, where comprehensive tobacco control programs have reduced smoking prevalence, the burden of tobacco-related disease has begun to decrease.73–75 Smoking can cause disease through a variety of mechanisms, which are reviewed in other chapters. However, some pathophysiologic effects persist after cessation. Smoking-related disease, therefore, will continue to be a major health problem for many decades.

Since Dr. Luther Terry released the first Surgeon General’s report on smoking and health in 1964,14 the prevalence of adult smokers in the United States has dropped from 40% to under 20%.75 Antismoking awareness has increased worldwide to the extent that smoking bans have become commonplace in public buildings, workplaces, and public transportation. In 1984, Surgeon General C. Everett Koop76 proclaimed that the United States’ number one health goal was to achieve a smoke-free society by the year 2000.” Unfortunately, this goal was not achieved, but the importance of the public health initiatives that followed, evidenced by the overall incidence of smokers in the adult population in the United States, continues to decrease.73–75 A more realistic goal of adult smoking reduction to 12% in the United States was put into place through the Healthy People 2010.77 Whether this goal will be obtained remains to be determined; however, it still highlights the importance of a smoke-free society. The greatest reductions in smoking have been in states with the most comprehensive tobacco control programs, supporting the effectiveness of currently available interventions.

Public health approaches to control smoking-related disease begin with the social factors that are key in initiating and maintaining smoking.51 The experience a child has with the initial attempts at smoking appear to be important as is an individual’s attitude toward smoking, that is, the “image” of the smoker, peer pressure, parental cigarette use, and availability.51,78,79 Social attitudes can account for very low smoking prevalence in some groups. These observations support attempts to place restrictions on smoking in public places and other efforts to “de-normalize” smoking.51

As in ancient America, the use of tobacco products has become well integrated into modern cultures worldwide. Tobacco is a multibillion dollar industry. In some regions, tobacco is a crucial cash crop in an agricultural economy. In addition, the manufacturing, distribution, marketing, and sale of tobacco products employ many individuals worldwide. Taxation on tobacco products has become an important means for the support of many governments. Thus, any changes in tobacco usage are likely to have economic impacts well beyond any health effects.

The use of tobacco not only has an economic role, but a cultural one as well. In some societies, for example, certain Native American tribes, tobacco usage has religious significance. In other groups, tobacco usage is associated with a strong cultural “image.” Often this image may have been created through direct efforts of the tobacco industry to market their product. In this regard, advertising messages promoting the image of the cigarette smoker as rugged, independent, and masculine or as sophisticated, independent, and feminine have been developed.80,81 While these images of cigarette smoking have their origins in advertising campaigns, the effectiveness of such marketing programs cannot be underestimated.51,79 The portrayal of these images in media, such as film, may help promote smoking, which supports restrictions on advertisements as part of public health initiatives directed at tobacco control.51,82,83 Whatever the reasons, cigarettes clearly have a cultural significance. The social and economic impact of tobacco usage, therefore, must be considered when attempting to deal with smoking as a public health problem.

In an effort to combat the public health ramifications of tobacco usage in the United States, the Master Settlement Agreement was signed into effect in 1998.84 It served as a measure to recoup what states had lost through Medicaid expenditures due to smoking-related illnesses and as a measure to fine the tobacco industry for deceitful actions. Four major United States tobacco companies awarded 46 states $206 billion to be paid over 25 years and to be utilized as the states saw fit. Four states had previously settled separately. Unfortunately, since its inception, many states have failed to use the funding for tobacco control causes, instead using it to fill budget deficits or to support other state programs. Among many other actions, the agreement also prohibited advertisements targeted at youth and permitted access to tobacco industry documents. Based on current understanding of the complex factors that interact to cause tobacco addiction, these approaches are rational. The issues are also complex and controversial. It is likely that social and public health interventions will continue to evolve and be part of ongoing political debate.

Smoking prevention. As noted above, smoking initiation is generally a pediatric problem.51 Precisely why some children begin smoking is not fully understood, although both social and genetic factors contribute as discussed above.51 Currently as many as 40% of American children will experiment with cigarettes, of whom one-fourth will eventually smoke by the twelfth grade.85 A number of factors are believed to contribute, including the child’s social environment and the child’s attitude toward smoking, which appears to be based, in large part, on the smoking behavior of parents, friends, and peer group role models.51,78,79 Attitudes toward smoking appear to be important factors leading to smoking initiation, which may depend, at least in part, on advertising and marketing programs, hence the effectiveness of bans on advertising. The reasons for initiating smoking, however, are not entirely environmental, as several lines of investigation (see above) suggest a genetic basis for smoking as well. These concepts support the basis for interventions to reduce smoking initiation. Interventions aimed at altering the social milieu have benefit.86 Participation in sporting activities is associated with lower rates of smoking initiation.48,87

A second approach to limiting smoking initiation is to restrict the sale of tobacco products to minors. Many states have legal restrictions on such sales. In many cases, however, these laws are not enforced. Active enforcement, however, can lead to a decrease in sales to minors88 and a decrease in both experimental smoking and in regular cigarette use among younger smokers,89 although the general effectiveness of these measures is unclear.90 For such measures to be effective, they must be uniformly enforced in the community, and vending machines must be made inaccessible to minors.91,92 Another approach to restrict tobacco usage by minors is taxation.93 While there is controversy over how “elastic” purchase of tobacco is,94 increasing price decreases use, and this effect may be particularly prominent among less addicted smokers.93 Inasmuch as adolescents may have less disposable income, the effect may be even greater among adolescents. Some analyses support an association between higher price, particularly through taxation and lower smoking initiation and prevalence.95 However assessment of the specific effectiveness is difficult methodologically.

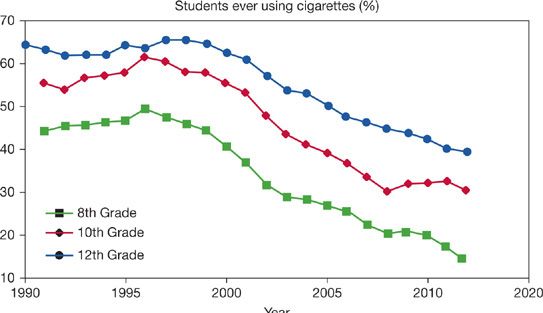

Measures aimed at restricting tobacco sales to minors may lead to a deferral for smoking initiation, as young adults remain at risk for52,53 smoking initiation. Thus, if measures are effective at delaying smoking initiation among children, parallel measures may also be required to affect smoking initiation among older adolescents and young adults. Currently available data suggest that smoking behavior among high school students decreased steadily since the initiation of efforts designed to reduce initiation (Fig. 41-1). There does not appear to be a corresponding increase in smoking among older individuals, which supports the concept that smoking prevention is a legitimate and achievable public health goal. While it is difficult to determine the effectiveness of specific public health initiatives,96 the evidence is clear that smoking rates can be decreased by population-based measures and that states with the most comprehensive programs have achieved the greatest gains.51,73–75

Figure 41-1 Prevalence of ever smoking among American Youth. (Data from Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Decline in teen smoking continues into 2012. Monitoring the Future Press Release. University of Michigan News Service, Ann Arbor.)

SMOKING CESSATION

BACKGROUND AND GENERAL APPROACH

BACKGROUND AND GENERAL APPROACH

Smoking should be regarded as a primary addictive disorder.97 This contrasts with the “classic” view of smoking as a “habit” or “life style choice.” An estimated 75% of Americans wish to quit but only 3% are able to achieve prolonged abstinence in any year, which indicates the involuntary nature of the established addiction.98 In addition, current concepts suggest smoking should be regarded as a chronic relapsing disorder. In this context, a “cessation attempt” should be regarded as an attempt to induce a remission. The abstinent smoker, moreover, should always be viewed as at risk for relapse. The goal for therapy is to induce a remission that is as durable as possible. However, the clinician needs to be prepared to reinduce remission in the event that relapse occurs. In this context, smokers who are “quit” should remain in active surveillance, and relapses should not be regarded as “failures.” In this model, the health consequences of smoking should be regarded as secondary effects. Importantly, there are health benefits of cessation that are well established. These are the subject of the Surgeon General’s Report (2014).

Current recommendations are to assess smoking and willingness to quit at every visit.97,99,100 Interestingly, success in quitting may be related to acute problems that may have motivated a patient to be willing to consider quitting (see Stages of Change).101 This acute motivation may be present even if the acute event is not directly related to smoking, and the clinician should be ready to utilize these windows of opportunity. In contrast, not inquiring about smoking can have adverse effects. Not asking is thought to send three messages: (1) that the physician does not care if the patient smokes; (2) that the physician does not have an effective intervention to offer; and/or (3) that the physician does not think that the patient will be able to quit. All of these “nonmessages” have negative effects, particularly as smokers gradually make the decision to quit. A sense of empowerment and control over the behavior is believed to be key to making and succeeding in a quit attempt102 and to subsequent risk of relapse.103 Inadvertently eroding a patient’s sense of mastery is an unanticipated adverse consequence of not asking about smoking. In addition, many patients are unaware of the potential available therapies; appropriate information can increase motivation to engage in quit attempts. Smokers unwilling to make a quit attempt should be encouraged as much as possible, provided with specific information if desired and reminded that the issue will be brought up again in the future.

Approach to a Quit Attempt

A smoking quit attempt should be approached in a similar way to induction of remission from cancer. As with cancer, each patient should be given the best chance of achieving remission. In general this will require two classes of intervention: nonpharmacologic approaches and pharmacotherapy, which should be used together to optimize success.

Evaluation

As with the management of any complex disease, smokers should undergo an initial organized assessment.97,100 Motivation or reason to quit and the patient’s confidence in their ability to stop smoking, that is, self-efficacy, should be assessed. For patients who indicate they are not currently interested in quitting, the goal is simple: to move them through the stages of change104 so a quit attempt will be made. For some, this may be as simple as providing information about health risks. For others, it may be information about effective interventions.

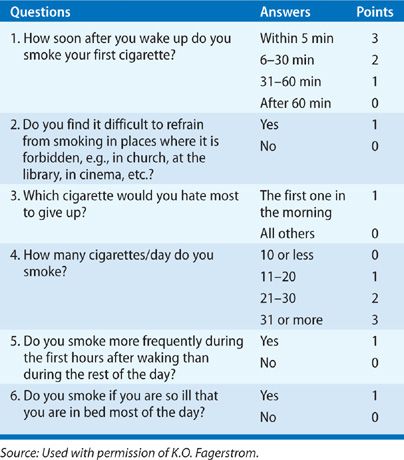

The intensity of addiction can be assessed with the Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence (Table 41-1).28 The most important question is time to first cigarette, and smokers who smoke within 30 minutes of awakening are usually heavily addicted to nicotine. These patients and those with Fagerstrom scores ≥7 comprise a group of individuals likely to benefit from nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) or varenicline. In contrast, patients with low Fagerstrom scores who are able to cope with smoke-free environments for an extended time period (>4 hours) without developing discomforting withdrawal symptoms, may not require NRT. For these individuals, the benefit of pharmacologic support is unknown.

TABLE 41-1 Items and Scoring for Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence

Past experience with quit attempts should be reviewed. Many patients will have a number of prior tries. Individuals who had particular difficulty with withdrawal symptoms should be prepared for this, and medications can be gauged to attempt to mitigate their intensity. Approaches that achieved abstinence, but were followed by relapse, should be considered as they are likely to succeed again. In these cases, interventions should be guided by reducing risks of relapse.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC APPROACHES

NONPHARMACOLOGIC APPROACHES

Nonpharmacologic approaches provide the smoker with guidance and support as progress is made through a quit attempt.97,99,100 It is likely that effective support improves adherence with pharmacotherapy and results in therapeutic synergy. In addition, conditioned responses, that is, cue-driven behaviors, are largely dealt with thorough behavioral strategies. This generally requires individual interviews to define individual smoking patterns. These patterns can also help identify situations that increase risk of relapse. In general, success increases with the intensity of support,97,99,100 but most smokers will decline referral to intensive programs and will receive only the support provided in the office setting. The remainder of this section summarizes commonly used approaches.97,99,100,105

Stages of Change and Smoking Cessation

The Stages of Change model has been very useful to guide behavioral support. Prochaska and DiClemente104 described the smoking cessation process as involving five stages: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. These stages are viewed as a continuum with smokers progressing sequentially through each stage. In the precontemplation stage, smokers are not interested in quitting smoking and will likely be nonresponsive to direct intervention. Smokers in the contemplation stage are considering quitting smoking and may be receptive to a physician’s advice about the risks and benefits of quitting. In the preparation stage, smokers are actively preparing to quit. The action stage encompasses both initial abstinence and the 6-month postcessation period. The maintenance period commences after the 6-month abstinence period. It is rare for a smoker to progress successfully through these stages in the initial quit attempt. The cycle will likely be repeated several times before smoking a prolonged abstinence, that is remission, is achieved. Thus the clinician must be encouraging and willing to support repeated attempts.

The National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) recommended model for smoking intervention is based, in part, on five NCI supported trials involving more than 30,000 patients and was later expanded by the Public Health Service.97,99,100 This approach, popularly referred to as “the five A’s,” emphasizes the role of medical professionals to ask patients about their smoking status, assess their willingness to make a quit attempt, advise smokers to stop, assist them in their stop smoking efforts, and arrange for follow-up visits to support the patient’s efforts. This approach utilizes brief intervention techniques and emphasizes the role of physicians as facilitators in the quitting process.

Simple advice has been assessed in a number of studies, and meta-analysis suggests a small but significant benefit of these limited interventions.100 Physician advice is effective both in the outpatient and hospital setting and may also be effective when given by letter, email, or telephone.106–108

Group Counseling

Group counseling programs for smoking cessation are offered by several commercial and voluntary health organizations. These programs are similar in content and typically include lectures, group interactions, exercises on self-recognition of one’s habit, some form of tapering method leading to a quit day, development of coping skills, and suggestions for relapse prevention. Group counseling programs sponsored by voluntary health organizations are generally the best cost value for smokers.97,99,100 However, these programs are generally limited to large metropolitan areas and are offered on a sporadic basis. One-year success rates associated with group counseling programs are typically in the 15% to 35% range.97,99,100 The high success rates are likely affected by selection bias, that is, participants may be more motivated to quit.

Gradual Reduction Versus Abrupt Abstinence

Gradual reduction or tapering intuitively appears to offer smokers the least abrasive way to stop smoking, and may be effective for some.109–111 However, gradually cutting down can be stressful when smokers attempt to reduce their cigarette use below their critical blood nicotine threshold. At this stage, smokers may begin to experience tobacco withdrawal symptoms. Rather than suffer prolonged discomfort, many taperers will gradually return to their customary cigarette levels and will not succeed in quitting. One of the negative consequences of tapering is that this method can strongly reinforce the smoker’s belief of their underlying need for cigarettes, that is, it can undermine self-efficacy. Combining tapering with pharmacotherapy to prevent withdrawal may be useful in this setting,110 but this is not an FDA-approved use for any medication. Abrupt abstinence is often stressful and can lead to tobacco withdrawal symptoms. However, within a few weeks of total abstinence, complete abstainers experience less frequent cigarette cravings than taperers and are less prone to relapse. Cigarette tapering is often a component of many group programs in which gradual cigarette reduction is used as a preparatory stage leading toward a target quit day.

Educational Techniques

For years, cigarette smoking was viewed as largely a social or psychological habit. As such, the ability to quit was viewed as a measure of personal motivation and psychological willpower. Motivation to stop smoking, combined with sufficient psychological resources, was seen as a driving force behind successful cigarette abstinence. Thus, if smokers could be educated about the health risks of cigarette smoking, they could theoretically become sufficiently motivated and psychologically empowered to quit. Unfortunately, anticipated benefits of the smoking cessation value of educational awareness messages were overly optimistic and simplistic. Educational programs to aid smoking cessation have produced disappointing results with high long-term failure rates.97,99,100 Nevertheless, education about smoking is still regarded as a useful activity, particularly when the information can address problems of specific interest to individual patients. In this regard, as noted above, a major predictor of success is “self-efficacy,” which is the patient’s sense that they are likely to succeed. Education that improves self-efficacy should be a therapeutic goal.

Other Modes

The goal of hypnosis in smoking cessation is to enable the smoker to achieve an altered state of consciousness to enhance the ability to quit. Controlled trials of hypnosis have generally been unable to document long-term smoking cessation efficacy. While one meta-analysis suggested the possibility of a treatment effect,112 this was not supported in another meta-analysis.113 Aversive conditioning is based on the premise that smoking is a learned response that can be extinguished by creating an association between smoking and a negative sensation. By design, adversive conditioning techniques can produce smoker discomfort and are now rarely employed. However, there are few recent studies, and a treatment benefit cannot be excluded.112 Acupuncture has been advocated, but controlled trials with “sham” acupuncture have not clearly demonstrated an effect. Meta-analyses have not been conclusive, but suggest the possibility of an effect.112,114

Resources Available

The resources available to support smoking cessation vary among communities. Some have readily available and affordable group programs, while these may be unavailable in other places. Toll-free tobacco quit lines are currently provided by many countries, including the United States and Canada. Telephone counseling is an effective smoking intervention.108 Thus, clinicians should encourage every smoker who wishes to quit to utilize a National Quit Line (e.g., in the United States: 1-800-Quit-Now). Additional support can be found via the internet using smokefree.gov. Using this approach, a smoker can choose to talk with a telephone specialist with either internet instant messaging or telephone support. Both methods are designed to provide smokers with a personalized quit plan that would be available in most clinical settings.

PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT

PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT

Three classes of agents, nicotine replacement, bupropion, and varenicline, are approved to aid smoking cessation.115 In addition, two other agents, clonidine and nortriptyline are supported by guidelines for “off-label” use as secondary agents. In addition, several other agents are under active investigation and have shown promise.97,99,100 As noted above, combination of nonpharmacologic support and pharmacotherapy optimizes success in achieving abstinence.97,99,100 The remainder of this section summarizes currently available pharmacotherapy.

Nicotine Replacement Therapies

Five nicotine replacement therapies are approved for use to aid in smoking cessation. Lozenges, polacrilex (gum), and transdermal systems are available over the counter (OTC). Nasal spray and a nicotine inhaler are available with a prescription. Other nicotine preparations, including nicotine toothpicks and e-cigarettes, have been developed and marketed as consumer products. Their efficacy and safety in smoking cessation remains undetermined. Initial concerns about potential hazards of concurrent smoking while using NRT led to warnings against this practice. However, the Food and Drug Administration recently (April, 2013) removed this warning from the OTC formulations, as the benefits of smoking cessation greatly exceed any potential hazards.

NRT is usually started on the scheduled quit day. The concept is to replace nicotine that would be absorbed from cigarettes and thereby reduce the intensity of withdrawal. Smokers will, however, experience withdrawal symptoms albeit with less intensity. In clinical trials, the five approved formulations have demonstrated about twofold increases in quit rates above placebo when used alone97,99,100 and one trial comparing gum, inhaler, and nasal spray found no difference in efficacy.116 They differ, however, in their pharmacokinetics.117 The transdermal systems provide the slowest delivery of nicotine, but maintain steady-state levels throughout the day. The other formulations allow episodic dosing. A common practice is to combine a transdermal system with another formulation, a “patch-plus” regimen.118,119 This allows a smoker to increase nicotine delivery at times of urges. Clinical trial data supports better success with combined NRT compared to monotherapy.97,99,100

Nicotine Polacrilex Gum Nicotine polacrilex gum was the first NRT to gain FDA approval. It is now commercially available OTC in 2 and 4-mg forms. In nicotine polacrilex, nicotine is bound to a resin that contains a buffering agent to improve delivery of nicotine through the buccal mucosa. The rate of chewing can influence the rate of nicotine release. In addition, acid foods or drinks convert nicotine base to its salt, which, because of its charge, does not cross the buccal mucosa. To be absorbed into the venous circulation, the nicotine-containing saliva must be retained in the mouth as long as possible. If swallowed, the nicotine can cause local irritation of the stomach. When absorbed into the portal circulation, high first-pass metabolism in the liver limits blood nicotine levels. If chewed properly, absorption takes place gradually, and blood levels peak after about 30 minutes.117 Ad lib use of 2-mg nicotine polacrilex is associated with blood nicotine levels less than 40% of customary smoking. The 4-mg dose is recommended for individuals who are heavier smokers or who have had discomforting tobacco withdrawal symptoms on the 2-mg dose.97 A fixed dosage regimen rather than ad lib usage may have better success,120 perhaps because it can produce higher blood nicotine levels. A common recommendation is that a smoker use one piece of gum every 1 to 2 hours for the first 6 weeks after quitting followed by gradual reduction over 6 weeks. Many smokers continue to use gum at times of craving for an extended time and some can use sufficient gum to sustain nicotine addiction without smoking.

Although effective in clinical trials, less successful results have been observed with nicotine gum in general practice and unsupervised settings. This may be due, in part, to requirement that the gum be chewed properly. Adverse effects from the gum include exacerbation of local effects: temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disease, trauma to dental appliances, sore jaw, oral irritation or ulcers, and excess salivation; effects from swallowed nicotine: hiccups; and effects from systemic absorption of nicotine: nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, palpitations, and headache. Use of the gum is not recommended in individuals with poor dentition or who have dental appliances.115

Nicotine Polacrilex Lozenge A nicotine polacrilex lozenge is also available “over the counter.” Chewing is not required, but acid food and/or beverages will impair absorption as with gum. Dosing, absorption, and duration of therapy with the lozenge are similar to those for the gum.121 Because it is not chewed, the lozenge does not share the problems of exacerbating TMJ disease or damaging dental appliances. Other side effects are similar to those of the gum.

Transdermal Nicotine The primary advantage of transdermal patch delivery systems are ease of use and controlled drug delivery. Several formulations are available “over the counter.” In general, they achieve nicotine blood levels roughly 40% to 50% of that achieved by customary smoking of about 30 cigarettes daily.117 Transdermal nicotine systems have been repeatedly found to reduce tobacco withdrawal symptoms and significantly enhance smoking cessation rates.97,99,100 Unlike nicotine polacrilex gum, transdermal nicotine systems and the nicotine lozenge have improved quit rates in primary care settings.101,122 This difference is likely due to the ease of patch use in this setting. The recommended use period for patches varies according to product, but a minimum of 4 weeks of therapy is probably required to help achieve long-term abstinence.

Patches are most commonly worn at night, which provides a level of nicotine when a smoker awakes. Often this is a time when the individual is at risk to relapse, since the low nicotine levels are associated both with withdrawal and with increased effect of the smoked cigarette. On the other hand, delivery of nicotine at night may disturb sleep, particularly through vivid dreams or insomnia. Spontaneous long-term use of the patch has not been observed, suggesting that the very slow kinetics of nicotine delivery with this system is insufficient to sustain addiction effectively.123 In addition, perhaps due to the partial replacement of nicotine, most smokers on patches will still experience some tobacco withdrawal symptoms during the first few days of quitting. While these symptoms will likely be less severe compared to quitting cold turkey, some patients will be tempted to smoke and wear patches. Early concerns about increased cardiac risk among individuals who smoked while wearing the patch have not been substantiated. In fact, reduced smoking may decrease cardiac events.124–126

Nicotine Inhaler The nicotine inhaler is a plastic nicotine-containing cartridge that fits on a mouthpiece. Nicotine is released when air is inhaled through the device, which is similar in size to a cigarette. The nicotine is not effectively delivered to the lungs as the particle size is too large. Rather, it is deposited and absorbed through the buccal mucosa, which results in pharmacokinetics that resemble nicotine polacrilex. Blood levels depend on the frequency of inhalations but can be about one-third of conventional smoking. Usual dosing is 6 to 16 cartridges per day for 6 to 12 weeks followed by gradual reduction over 6 to 12 weeks. Because the use of the inhaler recapitulates many of the actions associated with smoking: preparation of the device, oral stimulation, inhalation, etc.; it may be particularly effective in smokers for whom these behaviors are particularly strongly conditioned. In addition to the adverse effects described for the lozenge, the inhaler may cause irritation of the throat and mouth and may precipitate bronchospasm in individuals with reactive airways.

Nicotine Nasal Spray The nasal spray delivers nicotine to the nasal mucosa through which it is absorbed. It has the most rapid pharmacokinetics of the currently available nicotine replacement formulations but does not reproduce that of a cigarette.117 Nasal irritation is very common, particularly when initiating therapy. The recommended dose is one to two sprays per hour for 3 months with a maximum of 80 sprays per day. Because the spray can deliver large amounts of nicotine, it may be particularly effective for heavily addicted smokers. It also likely has a greater risk of nicotine overdose and may have a greater potential to sustain a long-term addiction.

Combination Therapy Although not approved by drug regulatory agencies, various combinations of nicotine replacement may have utility for selected individuals who need higher doses. In particular, combination of a transdermal system with an ad lib modality has been demonstrated to increase quit rates.97,99,100,122,127 Because of its increased success, it is recommended by some as initial therapy.115

Bupropion

Bupropion is approved as an antidepressant, and it is also effective as an aid for smoking cessation.97,99,100,128 It is believed to act by potentiating dopaminergic and noradrenergic signaling. The formulations for depression and for smoking cessation have different trade names, which has clinical relevance. First, an appropriate diagnosis is often required for reimbursement. Second, care is needed not to prescribe bupropion under one name to an individual already taking it under its other name, as over dosage can result.

In clinical trials, bupropion approximately doubles quit rates compared to placebo. Subjects with a history of depression, however, appeared to benefit from bupropion but did not with nicotine replacement, suggesting that bupropion may be a superior initial choice in such individuals. Combination of nicotine replacement with bupropion has been assessed and appears more effective than either agent alone.

The currently recommended dose is 150-mg daily for 3 days followed by 150-mg twice daily. Because the drug is excreted slowly, steady state-levels are achieved after 6 to 7 days. For this reason, the quit date should be scheduled after a week of therapy so that blood levels are established. As the 150-mg once daily dose was nearly as effective as the 150-mg twice daily,129,130 many practitioners use the lower dose routinely. The appropriate duration of therapy is not established. Clinical trials that formed the basis for approval treated for 7 weeks, although a 12-week course is commonly recommended. With prolonged therapy, there is an increase in secondary quits, and therapy for 1 year resulted in more quits than therapy for 7 weeks.

The drug is generally well tolerated. The most common adverse effects are dry mouth, insomnia, agitation, and headache. In combination with nicotine replacement, an increase in blood pressure may also occur. Bupropion reduces seizure threshold and a seizure risk of 0.1% has been reported. Because of its reduction in seizure threshold, bupropion is contraindicated among those predisposed to seizures, or with anorexia nervosa or bulimia.

In 2008, the FDA first noted that both bupropion and varenicline (see below) had a “possible association (with) suicidal events.”131 The benefits of smoking cessation were felt to outweigh any potential risks, and the medicines were not withdrawn from the market. However, both labels now contain a black box warning, suggesting that patients and their caregivers should be alerted to the possibility of neuropsychiatric symptoms, and patients should be monitored for changes in behavior, hostility, agitation, depressed mood, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. Most practitioners make a routine practice of reassessing patients 3 to 7 days after the quit day to both monitor for adverse effects and to provide additional support for the quit attempt. In this context, a second visit has been demonstrated to greatly improve success.97,99,100

Varenicline

Varenicline is a partial agonist at the (alpha4)(beta2) nicotinic receptor.132 As such, it can partially activate the receptor thereby mitigating withdrawal symptoms. In addition, by occupying the receptor, it can prevent nicotine from acting, and thus can reduce the rewarding and reinforcement effects associated with nicotine. This may be particularly important in preventing a lapse from becoming a full relapse once abstinence has been achieved. Both of these effects are supported by evidence from clinical trials.133–136 Varenicline consistently improves success in quitting compared to placebo by an effect of two- to fourfold.97,136 In addition, head-to-head trials have demonstrated superiority compared to bupropion.133,134 Fewer data compare varenicline to NRT, and a recent meta-analysis failed to show a difference, though superiority of varenicline could not be excluded.136

Varenicline is given orally. Usually medicine is started at 0.5-mg once daily for 3 days followed by 0.5-mg twice daily for 4 days and then 1-mg twice daily for 3 months. Individuals who have achieved abstinence at 3 months may have less relapse if therapy is continued for an additional 3 months. A quit date is usually recommended for 1 week after starting medication, but success has been reported with a broader window of quit dates from 1 to 5 weeks that was comparable to a fixed quit rate.137,138 This increased flexibility may be an advantage in starting a quit attempt when patients are seen for problems other than smoking cessation.

The most common adverse reactions are nausea, insomnia, visual disturbances, syncope, and skin reactions. The incidence of nausea is reduced with the dose titration described above.139 The most serious concerns with varenicline have been with psychiatric and cardiovascular side effects. Varenicline has the same boxed warning as bupropion, indicating that patients and their caregivers should be alerted to the possibility of neuropsychiatric symptoms, and patients should be monitored for changes in behavior, hostility, agitation, depressed mood, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts.131 However, clinical trials have failed to confirm psychiatric adverse effects, although they cannot be fully excluded.140 A meta-analysis that reported significant increase in cardiovascular events141 was felt to be methodologically flawed as it excluded studies with no events.142 A subsequent meta-analysis that included all available studies found no difference between varenicline and placebo, although a small difference may be present.142 Currently the FDA recommends that patients taking varenicline be alert for development of new or worsening symptoms of cardiovascular disease.143 Varenicline has also been associated with accidental injuries from falls and vehicular accidents.144 This has resulted in an FDA advisory regarding operating heavy machinery while using varenicline.145

Off-Label Agents

Clonidine Clonidine is an α-adrenergic agonist active in the CNS that is used to treat hypertension. A number of clinical trials have evaluated its efficacy in smoking cessation and have generally shown a trend toward benefit, although individual trials have generally not been statistically significant, and its use is supported by a meta-analysis.146 The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines suggest it can be used by experienced practitioners comfortable with the drug.97,99,100 Major adverse effects of clonidine are drowsiness, fatigue, dry mouth, and postural hypotension.

Nortriptyline Nortriptyline is a tricyclic antidepressant that has been evaluated for efficacy in smoking cessation in several studies. Both individual studies and meta-analyses support its benefit as an aid to smoking cessation,128,147 and it is also recommended as a possible second-line agent for practitioners comfortable with its use by the DHHS guidelines.97,99,100 Major adverse effects of nortriptyline include drowsiness and dry mouth. As with other tricyclics, CNS and cardiovascular effects, including arrhythmias, may occur.

Investigational Drugs

A number of other agents approved for other uses have also been assessed for smoking cessation. None are currently recommended off-label by established guidelines, although several are under investigation. These include topiramate, an antiseizure medication that has been evaluated for several addictions, including combined alcohol and tobacco addiction, and selegiline, an agent used as an adjunct in the treatment of Parkinson disease that has also shown promise in smoking cessation.148 Several other agents have been assessed. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants have been demonstrated to be without benefit.128 Opiate antagonists and anxiolytics have generally been without benefit,97,99,100,149 but buspirone remains controversial as studies have been mixed.

Nicotine vaccines are also under investigation. Antibodies can be made to nicotine, if it is presented bound to an appropriate carrier.150,151 The antibodies then bind nicotine reversibly. By slowing the delivery of nicotine to the brain, the vaccine would distort the pharmacokinetics of a cigarette. These investigational agents may have utility for long-term relapse prevention or for prevention of smoking initiation. However, phase 3 trials have not shown clinical benefits to date.150

PRACTICAL CONCERNS DURING THE QUIT ATTEMPT

PRACTICAL CONCERNS DURING THE QUIT ATTEMPT

Approach

As noted above, the first step is to have a patient willing to make a quit attempt. Current practice is to optimize the chance for success with each attempt. In general this will be achieved with nonpharmacologic support combined with pharmacotherapy. The more active the nonpharmacologic support the greater the likelihood of success. Patients will vary, however, in the type of support they will accept. It is also important to select an appropriate pharmacotherapy. Many practitioners initiate treatment with NRT, because of greater experience and reduced potential for adverse effects. The “patch-plus” regimen that combines a transdermal system with an ad lib formulation is often recommended.97,99,100,115 Bupropion may be more appropriate for individuals with a history of depression.152 Varenicline has the greatest efficacy, but is often reserved for secondary attempts to induce a remission from smoking.115 The quit date should be linked to the pharmacotherapy: generally this is 1 week after initiating bupropion or varenicline and on the same day as initiating NRT. Varenicline may offer some flexibility, with a quit date 1 to 5 weeks after starting treatment.138 A follow-up visit should be scheduled about 10 days after initiating bupropion or varenicline to check for side effects. A follow-up in the immediate postquitting period is associated with improved success. This may be particularly important for cessation attempts that begin in hospital.153

Withdrawal Symptoms

The first 3 days of abstinence are usually the most difficult. Tobacco withdrawal symptoms (Table 41-2) generally peak during the first 72 hours then gradually subside over a 3- to 4-week period. These symptoms can include restlessness, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, irritability, frustration, depression, and an almost unrelenting craving for cigarettes. Common suggestions to help smokers cope with these early withdrawal symptoms in addition to NRT can include: (1) Be active. Increased activity may curtail some of the drive to smoke. (2) Use deep breathing exercises. The simplest breathing exercise involves nothing more than extended breath holding followed by slow exhalation through pursed lips. (3) Avoid high-risk situations for smoking during the first 3 weeks of quitting. (4) Use plenty of cinnamon gum or chewable candies. (5) Combat strong urges to smoke: The urge to smoke will go away whether one smokes or not.