Chronic Mesenteric Ischemia: Open Surgical Repair

JESSE MANUNGA and PETER GLOVICZKI

Presentation

A 75-year-old female with cardiovascular risk factors significant for diabetes mellitus, type II; hypertension; hyperlipidemia; peripheral arterial disease; coronary artery disease; and remote history of tobacco abuse presents with complaint of postprandial abdominal pain with weight loss, diarrhea, and inability to eat without pain. Her surgical history is significant for bilateral lower extremity bypasses, cholecystectomy, coronary artery bypass grafting in 1995, and coronary angiography with stenting in 2011. She has diarrhea with five to six loose stools per day and has lost 30 pounds over the last 6 months. She denies bloating and distention, and endorses only minimal intermittent nausea. She is a thin lady in nonacute distress with a loud right carotid and abdominal epigastric bruit. She has 4+ pulses in the upper extremities, 3+ pulses on the right femoral, and 2+ left femoral pulses. She does not have palpable popliteal or distal pulses.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of chronic mesenteric ischemia requires a high index of suspicion. Because the condition is rare, it is not uncommon for the diagnosis to be delayed by up to a year or more from the onset of symptoms. Common causes of abdominal pain such as cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, malabsorptive disorders, diabetes, chronic pancreatitis, and hyperthyroidism must be ruled out. Patients with chronic mesenteric ischemia usually have disease in other vascular beds, and most would have undergone a battery of tests by the time they are seen by a vascular specialist. Furthermore, it is not uncommon for patients with this condition to undergo a cholecystectomy often without relief of symptoms. Unfortunately, advanced disease at the time of diagnosis adversely affects outcomes.

Workup

Prior to being seen at our institution, the patient had an upper endoscopy that was remarkable only for nonspecific erythema in the antrum. A colonoscopy revealed mild diverticulosis and internal hemorrhoids. A 4-hour gastric emptying scan was normal at 1 hour but delayed at 2 and 4 hours with 79% emptying at that time point. The patient was started on a gastroparesis type of diet without relief. A repeat endoscopy 8 months later was unremarkable for retained food particles in the stomach but revealed an 8-mm clean-based duodenal ulcer that was negative for malignancy. A Botox injection into the antrum made no difference in reliving her symptoms, and a subsequent capsule enteroscopy study was normal.

A fasting duplex ultrasound scan of the abdomen is the initial test to evaluate patients with suspected chronic mesenteric ischemia. Since most patients with this condition may have elements of chronic kidney disease, ultrasound has an added advantage of identifying affected patients without the use of a contrast medium. In patients with no contraindications, a CT angiography of the abdomen and pelvis is done since it helps rule out other causes of abdominal pain and also helps the clinician determine the best way to revascularize the patient.

Compared to superior mesenteric artery (SMA), the celiac access has lower velocity because of fewer branches. Sonographic criteria for diagnosis of greater than 70% stenosis of the celiac artery include the presence of retrograde common hepatic artery flow, peak systolic velocity greater than 200 cm/s, and an end-diastolic velocity greater than 55 cm/s with retrograde common hepatic flow being the most sensitive. Duplex criteria for diagnosis of greater than 70% SMA stenosis correlate best with peak systolic velocity greater than 275 cm/s and an end-diastolic velocity of greater than 45 cm/s.

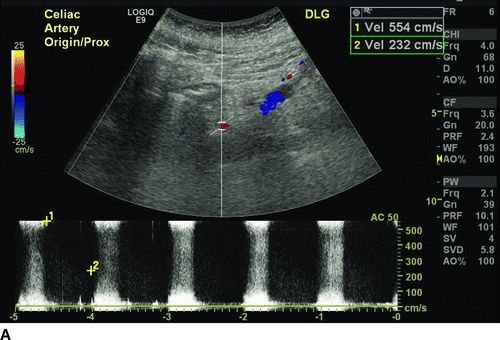

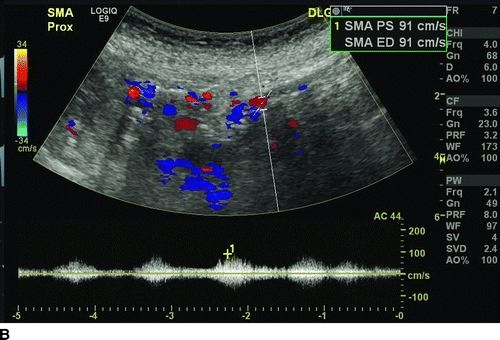

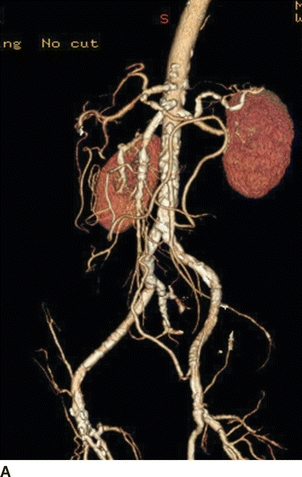

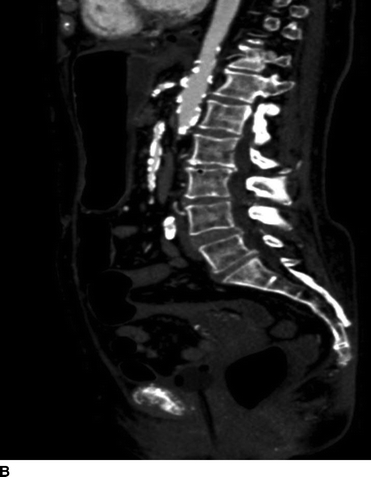

Our patient underwent a duplex ultrasound at our institution that revealed a velocity of 554 cm/s at the origin of the celiac trunk, 91 cm peak systolic as well as end-diastolic velocities in the SMA, and peak systolic velocity of 425 cm/s in the inferior mesenteric artery (Fig. 1). A CT scan of the abdomen confirmed a high-grade stenosis of the celiac and SMA with extensive calcification of the aorta, iliac, and mesenteric vessels (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 1 Preoperative ultrasound showing a high-grade stenosis of the celiac (A) and SMA (B). Note that the peak systolic velocity of the SMA is only 91 cm/s (below the threshold diagnosis of greater than 70% stenosis), but the end-diastolic velocity is higher also 91 cm/s, indicative of greater than 70% stenos.

FIGURE 2 CTA of the abdomen and pelvis showing heavily calcified aorta, celiac, SMA, and iliac vessels. Supraceliac aorta would be the ideal site for inflow, but the patient had severe cardiac disease making supraceliac clamping not ideal. Also, note that the patient is not a good candidate for an endovascular repair because of the long-segment disease in the SMA.

Discussion

Most cases of symptomatic chronic mesenteric ischemia result from ostial atherosclerotic lesions affecting at least two of the three main mesenteric vessels. However, conditions such as fibromuscular disease, aortic dissection, neurofibromatosis, rheumatoid arthritis, Takayasu’s arteritis, giant cell arteritis, polyarteritis nodosa, radiation injury, Buerger’s disease, systemic lupus, spontaneous mesenteric artery dissection, and drugs (cocaine and ergots) use also account for a handful of cases.

The natural course of asymptomatic mesenteric occlusive disease is unclear. Thomas and associates followed a group of 82 patients found to have, on angiography, 50% stenosis of at least one mesenteric artery. At a mean follow-up of up to 6 years, 10 patients had been lost to follow-up. None of the patients (0/45) with one or two vessel disease developed mesenteric ischemia. Eighty-six percent of the 15 patients with three-vessel disease either developed mesenteric ischemia or had symptoms of abdominal pain. The overall mortality in this cohort was 40%.

Therefore, high-grade stenosis or even occlusion of a single mesenteric vessel rarely results in symptomatic mesenteric ischemia because of the extensive collateral network between the three mesenteric vessels. Even in case of ostial occlusion of the SMA, most of the small bowel can still be perfused via collaterals from the celiac axis via the pancreaticoduodenal artery or inferior mesenteric artery (meandering artery). It is even conceivable for a patient with ostial occlusion of all three mesenteric vessels to be asymptomatic as long as they have a robust network of collaterals.

Oderich et al. in reviewing 229 patients treated for chronic mesenteric ischemia with either an open or endovascular repair at the Mayo Clinic reported that 96% of patients in this cohort presented with complaint of abdominal pain, followed by weight loss in 84% of patients, fear of food in 45%, and diarrhea in 40%, while only 24% of patients with this condition experienced nausea and vomiting.

Diagnosis and Treatment

The presence of high-grade stenosis of mesenteric vessels in an otherwise asymptomatic patient does not warrant treatment. However, asymptomatic patients with high-grade three-vessel stenosis should be followed closely. Once symptoms develop, revascularization is necessary because the disease often progresses to acute mesenteric ischemia. Park et al. reported the results of 58 patients treated at the Mayo Clinic from 1990 to 1999. In this series, 65% of patients with acute mesenteric ischemia had history of chronic, recurrent abdominal pain.

Since patients with mesenteric ischemia often have disease in other vascular beds, careful workup is needed prior to subjecting the patient to an open repair. Because of the multiple comorbidities and the advancement in endovascular techniques, mesenteric artery angioplasty and stenting has gained steam as a treatment modality of choice in patients with this condition. However, patients with heavily calcified and long-segment lesions, patients with small-diameter vessels (5 mm or less), those with tandem lesions, and patients with thrombus or debris and those who develop mesenteric ischemia as a result of radiation injury are poor candidates for endovascular repair. In these patients, open revascularization is offered after careful review of CT angiogram and medical clearance that often include cardiac and pulmonary evaluation.

Our patient’s CT angiography showed extensive disease in all three mesenteric vessels with severe calcification of the SMA. She had anatomical limitations making her an unfavorable candidate for an endovascular repair. Unfortunately, she had a markedly positive dobutamine stress test and went on to have coronary angiography with intervention prior to proceeding with open revascularization.

Surgical Approach to Open Repair

For patients who are not candidates for endovascular repair because of anatomical limitations, open repair is considered. Patients must be risk stratified prior to open repair. We find that patients older than 80 years of age, those with severe pulmonary and cardiac dysfunction or renal insufficiency (creatinine > 3.0) have an increased 30-day and 5-year mortality rates following open mesenteric revascularization. We define severe pulmonary dysfunction as FEV1 < 800 mL or DLCO < 50%, resting PCO2 > 50 mm Hg, resting PO2 < 60 mm Hg or on home oxygen. Severe cardiac dysfunction is defined as Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF) < 25%, NYHA III or IV angina pectoris, positive cardiac stress test, or myocardial infarction <90 days.

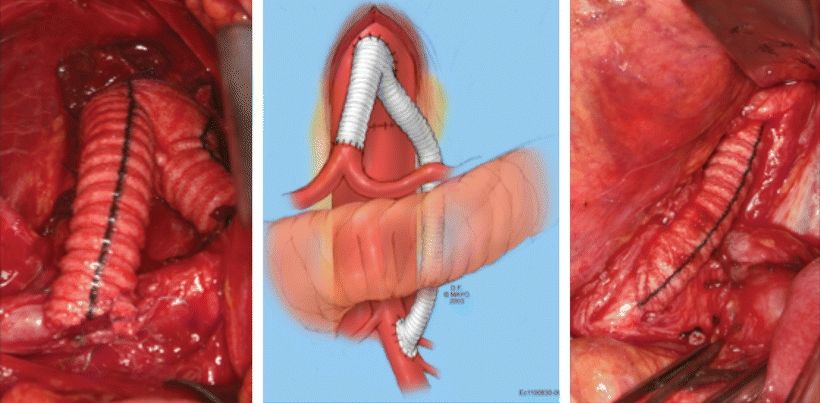

Our preference in low-risk patients with unfavorable lesions for endovascular intervention is to revascularize two of the three mesenteric vessels. In this case, we usually select the supraceliac aorta as our inflow source and perform a bifurcated graft with one limb to the SMA and the other to the celiac access (Fig. 3). After a careful review of the CT angiography and determination of the aortic clamping site, a midline incision is made from the xiphoid process to the umbilicus. Upon entering the abdominal cavity, the abdominal content is carefully examined, and bowel viability is assessed. Incising the left triangular and the gastrohepatic ligament exposes the supraceliac aorta. Care must be taken not injure any replaced left hepatic artery while dividing the gastrohepatic ligament. The posterior peritoneum is then opened and the median arcuate ligament is divided vertically to expose the aorta. A previously placed nasogastric tube will facilitate the identification of the esophagus, which, along with the lesser curvature of the stomach, is retracted leftward to expose the celiac access and its major branches. Mobilizing the neck of the pancreas and retracting it anteriorly exposes the origin of the SMA. The graft is fashioned, and the SMA limb is tunneled under the pancreas. The patient is systemically heparinized, and anastomoses are completed using running polypropylene sutures (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3 Intraoperative images and sketch of a supraceliac aorta to celiac and SMA bypasses using a bifurcated Dacron graft. Note that the SMA graft is tunneled under the pancreas. Care must be taken not to injure the pancreas during this maneuver.