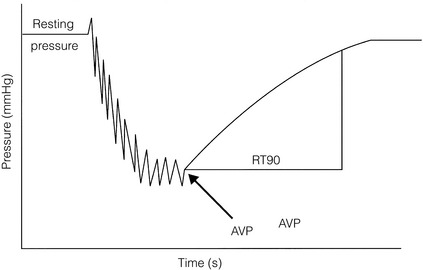

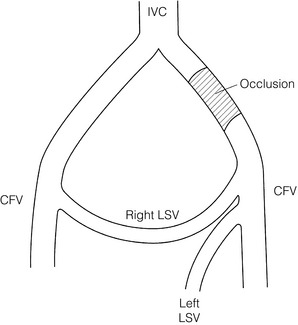

18 There are various conditions that can cause chronic lower limb swelling (Box 18.1). The three most common are chronic venous insufficiency, lymphoedema, and dependent oedema, which may be associated with inactivity and obesity. This chapter explores these three conditions further. The clinical features of CVI include skin changes, varicose veins, swelling, ulceration and pain. Varicose eczema presents as dry, scaly and itchy skin. The skin becomes friable and may become infected following scratching. Pigmentation, due to the deposition of haemosiderin in the tissues, produces a brown discoloration characteristic of CVI, which together with fibrosis leads to the clinical picture of lipodermatosclerosis around the ankle (Fig. 18.1). There may also be some loss of pigmentation resulting in pale skin changes called atrophie blanche. Ulceration is often precipitated by minor trauma and venous ulcers occur predominantly on the lower leg, more commonly around the medial aspect of the ankle. There may be surrounding eczema or pigmentation and frequently exudation of fluid that can cause maceration of the surrounding skin. In patients presenting with lower limb ulceration, approximately 80%1,2 will have evidence of venous disease and 10–25%3 of limbs will have Doppler-verified arterial disease. Approximately 12% will have coexisting diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis.4 Immobility is often a contributory cause, and can also cause stasis ulceration in isolation. The prevalence of CVI in the adult population lies between 2% and 9%, and may be higher in males than females.5,6 The most serious feature of CVI is ulceration, which is a distressing and debilitating condition. Leg ulcers affect approximately 1% of the adult population in developed countries, with 50% of ulcers having been present for more than 12 months, and 72% are recurrent.7 Within the UK, Australia, Sweden and Italy, overall rates for active ulceration range from 0.15% to 0.5%, and increase with age.8–12 In the UK, the total cost to the NHS has been estimated to be £230–600 million a year.13 During exercise in the normal individual, effective contraction of the calf muscles combined with vein patency and valvular competence aids venous return and reduces venous pressure in the lower leg from about 90 mmHg to 30 mmHg. Failure of any of these mechanisms may result in postambulatory venous hypertension, which is accepted as the underlying haemodynamic abnormality in CVI. The recognised causes are outlined in Box 18.2. Deep and superficial reflux: Most venous ulcers were thought to be secondary to previous DVT but duplex scanning has shown us that some patients have primary deep venous reflux. Isolated superficial venous incompetence without deep venous incompetence occurs in between 31%14 and 57%15 of patients with venous ulceration. Perforating vein reflux: The contribution of incompetent perforators to the development of CVI remains controversial. Isolated perforator incompetence occurs in only 2–4% of limbs with skin changes, and perforator incompetence is usually associated with reflux in the superficial or deep systems. On the other hand, the prevalence of incompetent perforators increases linearly with the clinical severity of CVI.16 There has been a recent trend towards treatment of incompetent perforating veins with laser and radiofrequency ablation, but the indications for this remain uncertain. In those cases where superficial and perforator reflux coincide, treating only the former results in healing rates of 95%.17 The pathophysiology is still not fully understood but the following two hypotheses exist: 1. White cell trapping hypothesis. Increased venous pressures lead to white blood cell plugging of capillaries, adherence of white cells to the endothelium and release of proteolytic enzymes. This leads to increased capillary permeability and tissue damage causing ulceration.18–21 2. Fibrin cuff hypothesis. A rise in venous pressure causes widening of the pores between the endothelial cells.22 This results in the passage of fibrinogen out of the intravascular compartment into the tissues, which then polymerises to form fibrin. A defective interstitial fibrinolytic system may also contribute to the build-up of fibrin.23 This acts as a barrier to oxygen, resulting in local tissue ischaemia and cell death, producing ulceration.24 Matrix metalloproteinases help remodel the extracellular matrix by protein degradation, and enhanced matrix metalloproteinase activity has been demonstrated in lipodermatosclerosis.25 This may also contribute to the development of ulceration. This includes clinical signs (C), aetiology (E), anatomical distribution (A) and pathophysiological condition (P), and is therefore known by the acronym CEAP. This system is helpful in comparing limbs for the purposes of research, although it is rather unwieldy for everyday use (Box 18.3). Various investigations may be used to examine the function of the venous system in the lower limb. Ambulatory venous pressure measurement: This provides direct measurement of the superficial venous pressure at the ankle. This is achieved by cannulation of a vein on the dorsum of the foot connected to a pressure transducer, amplifier and a recorder. The pressure changes recorded in the long saphenous vein in the foot during and after 10 tiptoe exercises are shown in Fig. 18.2. This investigation is an indicator of overall lower limb venous function including calf muscle pump function. These should include elevation of the legs at rest above the level of the heart. This helps to reduce oedema, decrease exudate from ulcers and accelerate regression of skin changes.4 Immobility, occupation, obesity and coexisting disease may also influence the development of skin complications and should be addressed. Placing the patient in bed reduces the venous pressure at the ankle to about 12–15 mmHg and will therefore usually lead to ulcer healing. However, this is not a treatment enjoyed by most patients and may increase the risk of DVT. It is therefore generally reserved for ulcers that have failed to heal by all other methods. Compression therapy remains the primary treatment for CVI. It provides symptomatic relief, promotes ulcer healing and helps in preventing ulcer recurrence. Applying a sustained graduated compressive force that is highest at the ankle and decreases proximally has been shown to reduce venous pressure at the ankle, increase femoral vein blood flow and increase venous refilling time. This improves venous function and can heal up to 93% of venous ulcers.28 Graduated elastic compression may be applied using either bandages or stockings but this is dependent on factors such as levels of exudate, amount of oedema and leg shape. It is important that these are applied by experienced staff as inexpertly applied compression can cause skin damage. Compression can also be used to treat mixed arterial and venous ulcers but this requires specialist assessment. Stockings are classed according to the pressure they exert at the ankle and are designed to provide a linear graduated decrease in pressure above this, although in practice this may not always be the case. Pressures of up to 60 mmHg may be produced by elastic stockings, and conventional pressure classes and indications are given in Table 18.1. Table 18.1 Conventional pressure classes of compression stockings Dressings: For those patients with venous ulceration, there are a wide variety of topical dressings available. Additional factors to consider in choosing a dressing are exudate, odour and patient comfort. Whatever dressing is chosen should be used in conjunction with treatment of the underlying venous insufficiency, usually by adequate graduated elastic compression. Simple non-adherent dressings are all that is required for many ulcers. Vacuum-assisted closure dressing systems are sometimes useful for deep ulceration and can be used under compression. There is recent evidence that they reduce time to healing at a lower cost when compared to conventional dressings.36 The Vulcan trial suggested that silver dressings made no impact on ulcer healing when compared to any other dressing, although this has been questioned as many of the ulcers treated with silver within the trial would not have had silver applied in clinical practice.37 Emollients: These soothe, smooth and hydrate the skin and are indicated for all dry or scaling disorders such as varicose eczema. Their effects are short-lived and frequent application is necessary. Preparations containing an antibacterial should be avoided unless infection is present. Superficial venous surgery: Superficial surgery may be of benefit in healing ulcers in situations of isolated superficial venous incompetence or combined superficial and deep venous incompetence. Surgery for isolated superficial venous incompetence may also reduce long-term recurrence rates. With the advent of minimally invasive techniques it may be possible to treat some patients who previously were not fit for conventional varicose vein surgery. These techniques include radiofrequency ablation (RFA), endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) and foam sclerotherapy, and are discussed in Chapter 17. Perforating vein surgery: There has been renewed interest in medial calf-perforating vein incompetence with the advent of subfascial endoscopic perforating vein surgery, and more recently with minimally invasive techniques such as EVLA and RFA. The evidence for the benefit of treatment of incompetent perforating veins by any of these methods is weak and the precise indications and benefit of perforator treatment remain unclear. Deep venous reconstruction: Worldwide experience of deep venous valvular reconstruction is limited as most patients with CVI can be managed very adequately with superficial venous surgery and the conservative measures described above. Therefore it is usually reserved for those patients with severe symptoms that prove resistant to conservative treatment. The benefit of deep venous reconstructive surgery is unclear as many of the published series have included ancillary procedures such as high saphenous ligation and stripping, and in the few series where the influence of these procedures has been excluded the numbers involved tend to be small or the follow-up short. A number of different procedures have been described and these are shown in Box 18.4. Venous bypass: Following DVT, recanalisation will occur in all affected venous segments in over 50% of limbs by 90 days.41 Many of these patients, however, will be left with functional outflow obstruction and deep venous reflux. Those that fail to recanalise will also have persistent venous outflow obstruction. If severe, this gives rise to a swollen leg, skin changes and venous claudication. Surgical bypass of an obstructed vein may be possible, but this should be reserved for those patients in whom there is measured evidence of outflow obstruction and in whom there are severe symptoms. As spontaneous improvement may occur due to the development of collaterals up to 4 years after DVT, surgery should not usually be considered before this time. Two principal surgical procedures have been described: 1. The femorofemoral crossover graft for iliac obstruction (Palma operation; Fig. 18.3).42 Only a small number of patients are suitable for this procedure, but in these patients long-term patency and relief of symptoms may be achieved in up to 70% of cases.43 The long saphenous vein on the unaffected side is used as a crossover graft. Figure 18.3 Femorofemoral crossover graft using the long saphenous vein (LSV) to bypass unilateral iliac obstruction. CFV, common femoral vein; IVC, inferior vena cava.

Chronic leg swelling

Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI)

Clinical features

Skin changes

Ulceration

Epidemiology

Aetiology

Macrocirculation

Microcirculation

Classification

Investigation

Functional measurements

Treatment

General measures

Graduated elastic compression

Class

Pressure at ankle (mmHg)

Indications

I

< 25

Mild varicosis, venous thrombosis prophylaxis

II

25–35

Marked varicose veins, oedema, chronic venous insufficiency

III

35–45

Chronic venous insufficiency, lymphoedema, following venous ulceration to prevent recurrence

IV

45–60

Severe lymphoedema and chronic venous insufficiency

Pharmacotherapy

Superficial venous intervention

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree