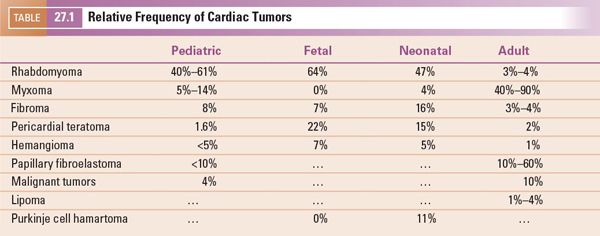

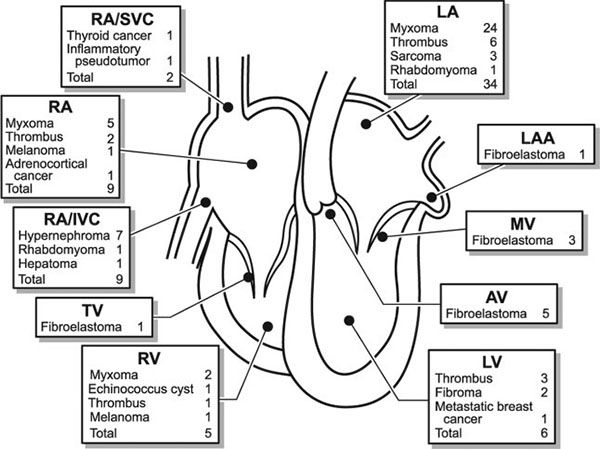

The term cardiac tumor is often used when referring to cardiac neoplasms. It is important to note, however, that it actually may refer to any mass-forming lesion within the heart–either neoplastic or otherwise. Non-neoplastic masses include such entities as thrombus, cyst, fat, abscess, ectopic tissue, and scar. Cardiac neoplasms include lesions that arise primary to the heart (either benign or malignant) and those that arise in other locations and metastasize to the heart (malignant by definition). Before the advent of echocardiography, the true incidence of primary cardiac neoplasms in children was elusive. With echocardiography, the incidence per echocardiogram performed approximates 0.08%. In children, the vast majority of primary cardiac neoplasms are histologically benign; fewer than 10% are malignant. Secondary or metastatic neoplasms of the heart are relatively rare in children. In children, rhabdomyomas are the most common primary cardiac neoplasm, whereas in adults, myxomas and papillary fibroelastomas are the most common (Table 27.1, Fig. 27.1). Echocardiography is the primary imaging modality to diagnose cardiac tumors, whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography can be useful adjunctive imaging modalities. Although most cardiac tumors in children are histologically benign, if their location in the heart jeopardizes cardiac, valvular, or conduction system function, then they can be associated with serious hemodynamic compromise and death.

SYMPTOMS AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

In general, the physical findings of cardiac tumors depend on the location and size of the mass. If the mass is causing restriction to flow through a valve, there may be a murmur suggestive of stenosis, or if the obstruction is severe, there may be evidence of reduced cardiac output and even shock. Obstruction of the tricuspid valve, especially in a neonate, can be associated with cyanosis. Mitral valve obstruction or pulmonary venous obstruction can cause pulmonary edema and features of pulmonary hypertension. If the mass is preventing normal closure of a valve, there may be a murmur of valvular insufficiency.

Myxomas and papillary fibroelastomas have the potential for embolism, either from themselves or surface thrombus, and physical findings associated with pulmonary or systemic embolic phenomenon can be apparent. Because these tumors can be sessile, sudden occlusion of a cardiac valve or a coronary artery can result in sudden death.

Pericardial teratomas may cause a pericardial effusion. Hence, the heart sounds may be muffled, and pulsus paradoxus can occur along with hepatomegaly. Teratomas can cause distortion of the heart, which can be associated with superior or inferior vena cava obstruction and the physical findings attendant to the obstruction.

FIGURE 27.1. Distribution of intracardiac masses removed from 75 adult patients at Mayo Clinic from 1993 through 1998. AV, aortic valve; IVC, inferior vena cava; LA, left atrium; LAA, left atrial appendage; LV, left ventricle; MV, mitral valve; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; SVC, superior vena cava; TV, tricuspid valve. (From Oh JK, Seward JB, Tajik AJ. The Echo Manual, 3rd ed, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. © 2006 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

RHABDOMYOMA

Rhabdomyomas are the most common primary cardiac neoplasm in infants and children, accounting for 50%–75% of these tumors. In fact, more than 90% of intracardiac tumors found prenatally are rhabdomyomas. They are characterized by well-circumscribed, nonencapsulated white or white-gray masses that consist of vacuolated cells (“spider cells”) filled with glycogen. They are classified as hamartomas and do not undergo mitotic division. They can be entirely intramural or extend into the atrial or ventricular cavities. Most frequently, they involve the ventricular walls and cavities. There are multiple rhabdomyomas in 90% of cases.

Most patients with rhabdomyomas are asymptomatic. However, sudden death has occurred with these tumors. Protrusion of the mass underneath the pulmonary or aortic valve can produce significant left or right ventricular outflow tract obstruction. As noted, arrhythmias can be associated with rhabdomyomas as well.

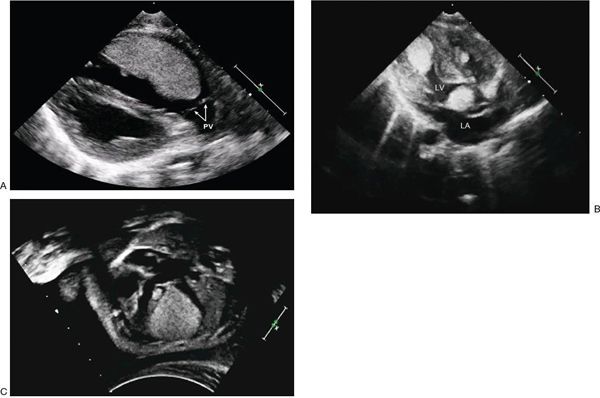

Rhabdomyomas are quite echogenic and usually are multiple, homogeneous, and well circumscribed. They frequently have a speckled pattern. Although they can occur anywhere in the heart, usually they are present within the ventricular walls and often have a variable amount of extension into the ventricular cavity (Fig. 27.2). Occasionally they can be pedunculated. In contrast to thrombi, myxomas, vascular tumors, or fibromas, rhabdomyomas do not have echolucent areas indicative of hemorrhage or areas of calcification. These tumors can cause either right or left ventricular outflow tract obstruction but characteristically do not embolize. Serial echocardiography often reveals decreasing rhabdomyoma size, and, if present, right or left ventricular outflow tract obstruction may decrease over time.

There is a strong association of rhabdomyomas with tuberous sclerosis complex, and approximately 80% of children with these tumors have features thereof. Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal dominant condition caused by mutations in the genes TSC1 and TSC2, encoding for the regulatory proteins hamartin and tuberin, respectively. It is manifest clinically by subungual fibromas, café-au-lait pigmentation, and subcutaneous nodules. About half of patients with tuberous sclerosis will have cardiac rhabdomyomas, but upwards of 80% of fetuses with rhabdomyomas have tuberous sclerosis. This decrease in prevalence with age is likely because of the propensity of the lesions to undergo spontaneous regression.

Because rhabdomyomas frequently regress, if they are causing no hemodynamic compromise and there appears to be no potential for them to embolize, they should be observed. Operation is indicated to remove them only if they are causing hemodynamic compromise or there is high risk of embolization. Recently, pharmacologic inhibition of the mTOR pathway has shown promise in hastening the regression of these tumors without surgical intervention.

MYXOMA

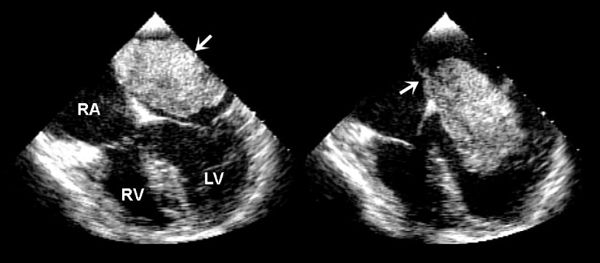

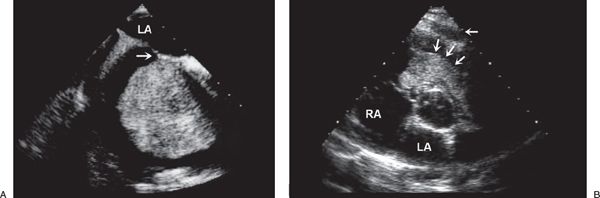

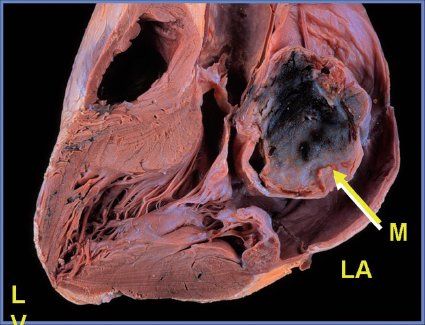

Considering patients of all ages, cardiac myxomas are the most common cardiac tumor generally coming to medical attention in the third to sixth decades of life. In children, however, they are second in frequency to rhabdomyomas. Three-quarters of myxomas are located in the left atrium (Fig. 27.3), and 25% are in the right atrium (Fig. 27.4A) They can be readily demonstrated by echocardiography in the subcostal and apical views. They occur rarely in the ventricles (Fig. 27.4B). They are friable, pedunculated, red lobular tumors (Fig. 27.5). They are histologically characterized by the presence of bland spindled cells proliferating in a myxoid background that contains numerous small blood vessels. In the atrium, the stalk typically is attached to the atrial septum (Fig. 27.6). When they occur in multiples, it is usually in the context of the Carney complex (myxoma syndrome). They are not believed to undergo malignant transformation.

FIGURE 27.2. A: Large right ventricular rhabdomyoma demonstrated as a homogeneous echogenic mass along the anterior wall of the outflow tract. This infant had successful resection of the obstructive mass. Pulmonary valve (PV). B: Large rhabdomyomas in the left ventricle (LV) apex and outflow tract. The LV outflow mass was successfully resected (Video 27.1). C: Fetal echocardiograph in four-chamber projection demonstrating multiple rhabdomyomas in the septum and lateral wall of the left ventricle. One large rhabdomyoma causes compression of the left ventricular cavity (Video 27.2). (Courtesy of Drs. Alexander Sokolov and Galina Martzinkevich, Tomsk Cardiac Center, Tomsk, Russia.)

In infants, a myxoma can mimic a variety of congenital heart defects. In children, they frequently cause relative obstruction of the tricuspid or mitral valve. Doppler echocardiography is very helpful to evaluate the hemodynamic impact of these tumors on atrioventricular valve inflow. Large myxomas can entirely obstruct the valve and be lethal. Partial obstruction of the mitral valve can cause pulmonary hypertension. The symptoms of valvular obstruction can be positional as the mass moves in and out of the valve orifice, with changing from standing to supine positions. The patient may experience positional dyspnea, dizziness, and/or syncope. Myxomas can be associated with the triad of (a) valvular obstruction, (b) embolic events, and (c) systemic illness. Constitutional symptoms, likely due to tumor elaboration of interleukin-6 (IL-6), include fever, malaise, weight loss, arthralgias, and myalgias. The patient also may exhibit anemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated sedimentation rate, and elevated gamma-globulin levels. The manifestations of a myxoma can be protean and be confused with rheumatic fever, endocarditis, septicemia, myocarditis, and collagen vascular diseases.

FIGURE 27.3. Large myxoma in the left atrium attached to the atrial septum. Movement with the cardiac cycle can be appreciated in these systolic (left) and diastolic (right) images. (From Oh JK, Seward JB, Tajik AJ. The Echo Manual, 3rd ed, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. © 2006 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

FIGURE 27.4. Myxoma. A: Large myxoma in the right atrium. B: Parasternal short-axis view demonstrating a large myxoma in the right ventricular outflow tract (arrows). In young patients, a myxoma in an unusual location is probably related to familial myxoma syndrome. RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium. (From Oh JK, Seward JB, Tajik AJ. The Echo Manual, 3rd ed, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. © 2006 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

The Carney complex is a familial form of myxoma that is manifest by the presence of a set of findings, including myxomas (cardiac or extracardiac), lentigines (Fig. 27.7), endocrinopathies, as well as a number of extracardiac neoplasms. If Carney complex is suspected, appropriate genetic screening should be undertaken in the patient and their family members, as well as surveillance for cardiac myxomas.

FIGURE 27.5. Pathologic specimen demonstrating a large myxoma (M) in the left atrium (LA).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree