Cardiac Tumors

Allen Burke

Jean Jeudy Jr.

Renu Virmani

Overview

Cardiac masses can be considered in three groups: nonneoplastic masses, such as mural thrombi, which can mimic neoplasms; primary neoplasms, either benign or malignant; and metastatic tumors, which may be endocardially based, simulating primary lesions. In surgical series, primary lesions are by far the most common. In autopsy series that include incidental cardiac or pericardial deposits, metastatic tumors are much more common. Pediatric cardiac tumors comprise a group of hamartomatous lesions that are best considered separately, because many of these tumors do not occur in adults and have no extracardiac counterparts; they are not discussed in this chapter.

The type of tumor expected in the heart varies greatly by patient age (Table 39.1) and site in the heart (Table 39.2). Overall, myxoma is by far the most common primary cardiac tumor.

The estimated frequency of primary cardiac neoplasms, based on population estimates, ranges from 0.0017% to 0.33% (1). Primary tumors may arise in adults most frequently from the endocardium, followed by the cardiac muscle, and, most infrequently, the pericardium. Interestingly, the rate of metastatic lesions is the reverse: the pericardium is by the most common site especially for epithelial malignancies, with endocardial lesions common only for those tumors growing into the great veins.

Echocardiography has the best spatial and temporal resolution of the cardiac imaging modalities, and it provides excellent anatomic and functional information (2,3). It is the optimal imaging modality for imaging small masses (<1 cm) or masses arising from valves. Echocardiography can image velocities with Doppler, which allows for assessment of presence, degree, and location of obstructions to blood flow or valve regurgitation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has the highest soft tissue contrast of the imaging modalities, and this property makes it the most sensitive modality for detection of tumor infiltration; it is also more manipulable than other imaging modalities (4). For example, a T2-weighted standard or fast spin echo sequence distinguishes tumors with high water content, such as hemangioma, from tumors with low water content, such as fibroma. MRI can characterize tumor vascularity with intravenous contrast and permits assessment of wall motion allowing for characterization of ventricular function, inflow or outflow obstruction, and valve regurgitation. Electrocardiographic (ECG)-gated CT scans with multidetector scanners or electron beam scanners are also very useful for cardiac imaging. The advantages and disadvantages of CT are intermediate between those of echocardiography and MRI (5). CT scanners have spatial resolution, better than that of MRI, but not as high echocardiography. CT has better soft tissue contrast than echocardiography and can be used to characterize fatty content and calcifications (Fig. 39.1) definitively; however, the overall soft tissue contrast and the ability to characterize tumor infiltration and tumor type are less than those of MRI. Catheterization provides indirect and nonspecific imaging based on filling defects within the cardiac chambers (6), allows endomyocardial biopsy for biopsy, and provides selective coronary angiography before surgical resection of an intramyocardial tumor.

Benign Tumors and Tumor-like Lesions

Mural Thrombi

Most mural thrombi occur in association with underlying heart disease (7) or after cardiac surgery, including mitral valve replacement or the Maze procedure. Left atrial thrombi are frequently associated with mitral valvular disease, especially mitral stenosis, and thrombi occur in either atrium in patients with atrial fibrillation (7). Mural thrombi are occasionally removed surgically and may be clinically and pathologically misdiagnosed as myxomas (8).

Mural thrombi in the absence of heart disease occur in any chamber but are most common in the right atrium (7). In the majority of patients, a coagulation defect is either suspected or documented. One of the more common coagulopathies diagnosed in patients with mural thrombi is the antiphospholipid syndrome, but a wide variety of conditions may be a predisposing factor, including essential thrombocytosis and Behçet disease. If venous emboli become dislodged into the right ventricle, a mistaken preoperative diagnosis of right ventricular tumor may be made.

TABLE 39.1 Primary Cardiac Tumors: Frequency and Mean Age at Presentation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 39.2 Cardiac Tumors, by Site and General Imaging Characteristics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

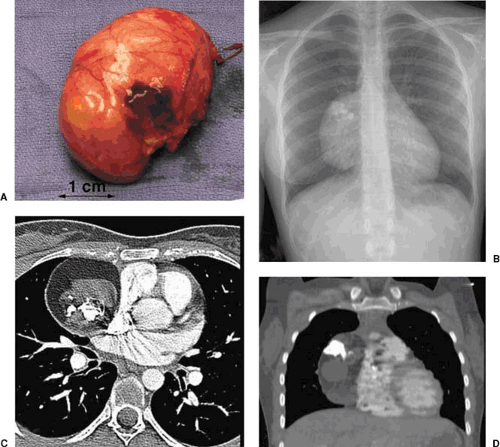

Echocardiography, cineangiography, and MRI have been used to make a diagnosis of mural cardiac thrombus both in patients with organic heart disease and in patients with presumed coagulopathies and normal cardiac function. In some cases, the imaging findings are indistinguishable from primary cardiac tumors, such as myxoma, when the location is intra-atrial (Fig. 39.2).

On occasion, there can be a thin stalk at the attachment site, mimicking myxoma, or no attachment site at all (ball thrombus). Histologically, organized thrombi are characterized by layers of degenerated blood cells with a margin of granulation tissue and eventually fibrosis.

Ectopias

Cystic Tumor of the Atrioventricular Node

These curious endodermal inclusions may represent a form of ultimobranchial heterotopia (9). Most patients have congenital heart block, and almost three of four are female. Most tumors occur sporadically, but there is an association with cysts of endocrine organs and other midline defects, such as ventricular septal defect, nasal septal defect, encephalocele, thyroglossal duct cysts, and absent septum pellucidum (10).

Thyroid Heterotopia

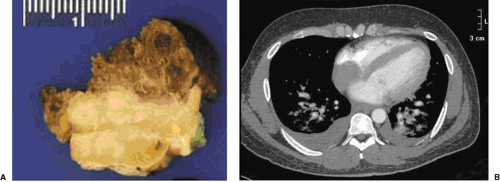

When ectopic thyroid occurs in the myocardium, it is called struma cordis. The right ventricular outflow is generally involved (11) (Fig. 39.3), although left ventricular obstruction has been reported. The condition is believed to occur early in embryogenesis, when part or all of the functioning thyroid tissue becomes lodged in the ventricular outflow region. Radioiodide imaging is diagnostic (12). Although pulmonary stenosis with right ventricular hypertrophy may occur, most patients are asymptomatic (11). Histologically, one sees follicular structures containing colloid; if there is any difficulty in diagnosis, immunohistochemical stains for thyroglobulin may be performed.

Papillary Fibroelastomas

Also known as fibroelastic papilloma, this unusual lesion occurs exclusively on endocardial surfaces, most commonly on valve leaflets, like Lambl excrescences (13). No gender predominance is noted, and there is a wide range of age at presentation, with a mean age of approximately 60 years (13). Papillary fibroelastomas occasionally occur in areas of previous endocardial damage or in patients with preexisting heart disease (14). Most symptoms arise from left-sided lesions that shower fibrin clots into the cerebral circulation or prolapse into the coronary orifice. The most common symptoms are transient neurologic defects, myocardial ischemia (15), and, rarely, sudden death. Papillary fibroelastomas of the cardiac valves demonstrate typical echocardiographic features (16). Transesophageal echocardiography is helpful in cases of rare sites, such as the venae cavae or atria (17). Three-dimensional echocardiography may provide enhanced imaging (18). Unlike Lambl excrescences, papillary fibroelastomas can become quite large and occur on any valve surface or area of the endocardium (19). Thrombi may occur on the surface of the proliferation, and dislodged clots are responsible for embolic symptoms. Histologically, they are avascular papillary structures lined by endothelial cells. They are often mistaken for cardiac myxomas, which are vascular and of heterogeneous cell types. Papillary fibroelastoma is treated curatively by surgery, whether there are preexisting embolic symptoms or a lesion is incidentally discovered. Asymptomatic patients can be treated surgically if the tumor is mobile, because the tumor mobility is the independent predictor of death or nonfatal embolization. Asymptomatic patients with nonmobile lesions can be followed-up closely with periodic clinical evaluation and echocardiography, and they can receive surgical intervention when symptoms develop or the tumor becomes mobile (13). Recurrences are rare, and valve-sparing surgery should be considered whenever possible, because partially resected lesions do not always regrow (20).

Cardiac Hamartomas

The term hamartoma has no specific meaning, but it embraces a group of tumors that are not neoplasms, may be associated with syndromes involving extracardiac sites, and are composed of recognizable histologic issue types often in a haphazard or disorganized growth pattern. Recurrences are rare after excision, and the lesions have no metastatic potential. In the heart, the most common hamartomas include rhabdomyomas and Purkinje cell hamartomas/histiocytoid cardiomyopathy; because these lesions occur exclusively in children, they are not discussed further here. Hamartomas of mature cardiac myocytes and adult forms of rhabdomyomas are extraordinarily rare and are not addressed.

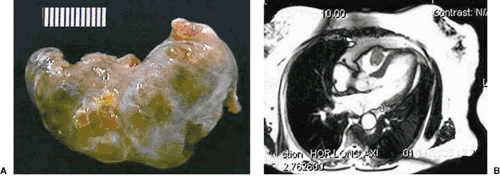

Cardiac fibroma is a nonneoplastic mass of fibrous tissue that occurs within the heart walls, usually ventricular free wall or interventricular septum. Most cardiac fibromas are discovered in children and often before 1 year of age (21). However, cases are also reported in adults and even as incidental finding in the elderly (21). Symptoms relate to the site of tumor, which is most commonly the ventricular septum, followed by the free walls of the left and right ventricle. Approximately 3% of patients with Gorlin syndrome have cardiac fibromas (22). At echocardiography, fibromas typically appear as a large, well-circumscribed, solitary mass in the septum or ventricular free wall (5), and in some cases they may be confused with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (23). The tumors are frequently very large and may cause obstruction, which can be assessed by color Doppler. MRI likewise shows a large, solitary, homogeneous myocardial mass centered in the ventricles (5). Because of the fibrous nature of the tumor, the signal intensity is often less than that of adjacent uninvolved myocardium, and contrast-enhanced imaging usually demonstrates a hypoperfused tumor core. CT also shows a large, solitary, ventricular mass, which usually has low attenuation on CT, which may also detect calcification, a helpful feature in making a confident diagnosis (5). Cardiac fibroma is benign, but its nature of slow but continuous growth may cause conduction defects and arrhythmias. Extension into the ventricular free walls may result in atrioventricular

valve inflow or arterial outflow obstruction. Spontaneous regression, as can occur with congenital rhabdomyoma, has not been observed. If the mass is too large for resection, heart transplantation may be considered with or without pretransplant palliation or cardiomyoplasty (24). However, favorable late results even after incomplete excision have been reported (25).

valve inflow or arterial outflow obstruction. Spontaneous regression, as can occur with congenital rhabdomyoma, has not been observed. If the mass is too large for resection, heart transplantation may be considered with or without pretransplant palliation or cardiomyoplasty (24). However, favorable late results even after incomplete excision have been reported (25).

Lipomatous hypertrophy of the atrial septum is an exaggeration of the normal accumulation of brown fat within the atrial septum, which is only weakly associated with obesity. In the last 2 decades, transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography, CT, MRI, and positron emission tomography (PET) have allowed antemortem diagnosis (26,27). Lipomatous hypertrophy is removed incidentally during open heart surgery for other causes or for relief of cardiac symptoms, such as supraventricular arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, or vena caval obstruction. The indications for surgery are somewhat controversial, because the detection of incidental masses may lead to unnecessary surgery for a benign lesion that may simply be an exaggeration of normal features. Histologically, there is a mixture of mature and brown fat, which ultrastructurally contains abundant mitochondria (28). Entrapped, enlarged myocytes are common and may lead to the false diagnosis of sarcoma, or the brown fat clusters may be mistaken for lipoblasts.