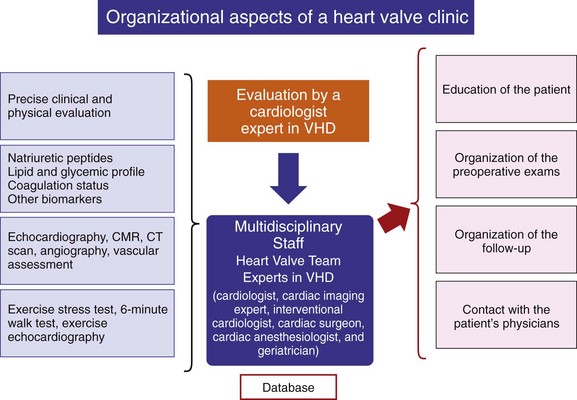

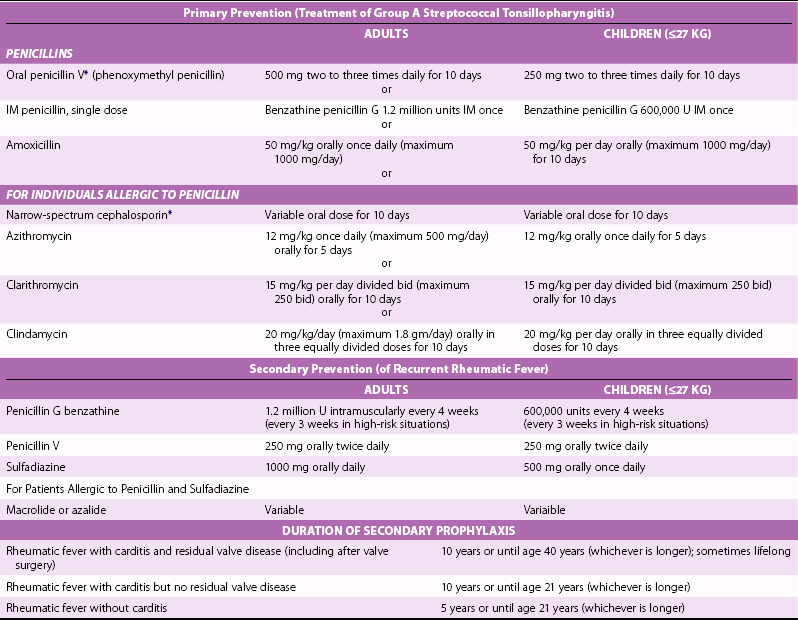

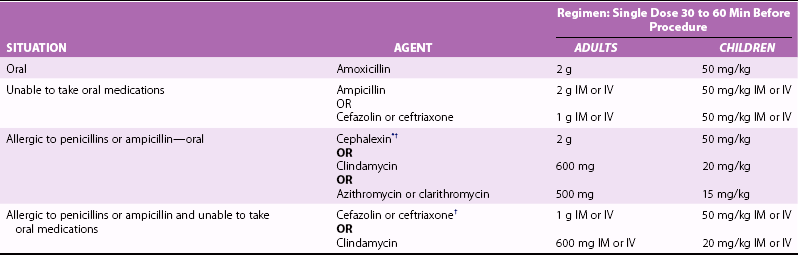

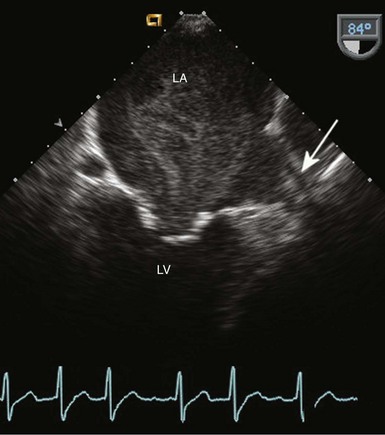

Chapter 9 MONITORING DISEASE PROGRESSION MEDICAL THERAPY OF VALVULAR HEART DISEASE Prevention of Left Ventricular Contractile Dysfunction Prevention of Left Atrial Enlargement and Atrial Fibrillation Prevention of Pulmonary Hypertension MANAGEMENT OF CONCURRENT CARDIOVASCULAR CONDITIONS NONCARDIAC SURGERY IN PATIENTS WITH VALVE DISEASE In patients with valvular heart disease, the basic principles of management are to: • Obtain an accurate diagnosis of the specific valvular lesion and quantitative disease severity using Doppler echocardiography and other advanced imaging modalities • Prevent complications of the disease process, such as endocarditis, atrial fibrillation (AF), and embolic events • Periodically reevaluate ventricular size and function to identify early ventricular dysfunction and optimize the timing of surgical or percutaneous intervention • Provide optimal management of associated conditions • Provide patient education regarding the disease process, expected outcomes, and potential medical or surgical therapies These goals are best met with an interdisciplinary health-care team structured as a Heart Valve Clinic. Valvular heart disease is relatively uncommon in comparison with other cardiac conditions, such as coronary disease, heart failure, and AF, so general cardiologists often have little experience in managing the complex care that patients with valvular heart disease need. Data from the Euro Heart Surveys shows that many patients are not treated according to current guidelines—some patients are inappropriately denied interventions that would improve survival and quality of life; others undergo intervention earlier in the disease course than necessary. 1 In addition, optimal decision making requires input from cardiologists with expertise in valve disease, interventional cardiologists, imaging specialists, and cardiovascular surgeons. The European Society of Cardiology has published a position paper on the need for Heart Valve Clinics with specific recommendations for goals ( Table 9-1), patient population, clinic structure ( Figure 9-1), and the tasks for each member of the Heart Valve Clinic team. 2 TABLE 9-1 Specific Aims of the Heart Valve Clinic • To improve the outcome of patients with valvular heart disease (VHD) • To ensure optimal communication and coordination among all health-care professionals involved in the management of the patient with VHD • To perform or coordinate relevant diagnostic tests to obtain a complete evaluation of the severity of VHD and its implications for symptomatic status, cardiac function, and risk of future adverse events • To ensure rational utilization of diagnostic tests according to the recommendations of international guidelines • To standardize and centralize the collection and interpretation of the results of these tests and provide all health-care professionals involved in management of the patient with complete and accurate information concerning the diagnosis and prognosis of VHD • To optimize patient education concerning compliance with medical therapy and prompt reporting of symptoms relating to VHD • To assist the general cardiologist with regard to prescription of appropriate pharmacologic treatment and determination of the most appropriate timing for clinical evaluation, imaging, exercise testing, and follow-up before and after valve procedures • To assist the general cardiologist in the determination of the optimal timing and mode of intervention • To enhance adherence to international guidelines for the evaluation and management of patients with VHD From Lancellotti P, Rosenhek R, Pibarot P, et al; ESC Working Group on Valvular Heart Disease Position Paper—heart valve clinics: organization, structure, and experiences. Eur Heart J 2013;Jan 4. FIGURE 9-1 Functioning of the advanced heart valve clinic. In patients with a cardiac murmur, the first step is clinical assessment based on the history and physical examination.3,4 If clinical evaluation indicates a high likelihood of significant valvular disease, the next step is echocardiography to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate valve anatomy and function.5,6 A condensed version of indications for echocardiography in patients with suspected or known valve disease is shown in Table 9-2. 7 TABLE 9-2 Indications for Echocardiography in Adults with Suspected or Known Valvular Heart Disease Suspected Valvular Disease • Cardiac murmur in a patient with cardiorespiratory symptoms • Murmur suggestive of structural heart disease, even if asymptomatic: Native Valve Disease • Initial diagnosis and assessment of hemodynamic severity • Assessment of left and right ventricular size, function, and hemodynamics • Reevaluation for changing signs or symptoms • Assessment of changes in valve or ventricular function during pregnancy • Periodic reevaluation as shown in Table 9-10 • Assessment of pulmonary pressures with exercise in patients with mitral stenosis when there is a discrepancy between symptoms and resting hemodynamics • TEE before balloon mitral valvotomy in patients with mitral stenosis • Initial diagnosis and assessment of hemodynamic severity • Initial evaluation of left and right ventricular size, function, and hemodynamics • Assessment of aortic regurgitation when aortic root enlargement is present • Reevaluation with a change in symptoms • Periodic reevaluation even in asymptomatic patients, as in Table 9-10 • Reassessment of valve and ventricular function during pregnancy • Detection of valvular vegetations with or without positive blood culture results • Characterization of hemodynamic severity with known endocarditis • Detection of complications, such as abscesses, fistulas, and shunts • Reevaluation in high-risk patients (virulent organism, clinical deterioration, persistent or recurrent fever, new murmur, persistent bacteremia) Interventions for Valvular Disease • Selection of alternate therapies for mitral valve disease (balloon mitral valvotomy, surgical valve repair vs. replacement) * • Monitoring interventional techniques in the catheterization laboratory (3D TEE, ICE, or TTE) • Intraoperative TEE for valve repair surgery • Intraoperative TEE for stentless bioprosthetic, homograft, or autograft valve replacement surgery • Intraoperative TEE for valve surgery of infective endocarditis Prosthetic Valves • Baseline postoperative study (at hospital discharge or 6-8 weeks) • Annual evaluation of bioprosthetic valves after 5 years of implantation • Changing clinical signs and symptoms or suspected prosthetic valve dysfunction * • Prosthetic valve endocarditis: *Transesophageal echocardiography usually required. Summarized and updated from Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing Committee to Revise the 1998 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease) developed in collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:e1–148. In a patient with cardiac or respiratory symptoms and a cardiac murmur on auscultation, it is prudent to obtain an echocardiogram to evaluate for possible valvular disease. When symptoms are present, it is difficult to reliably exclude significant valvular disease with physical examination because findings may be subtle. 8 For example, some patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) have only a grade 2 or 3 murmur on examination and the carotid upstroke may appear normal because of coexisting atherosclerosis.9–11 Diagnosis may be even more difficult in other situations. For example, only 50% of patients with acute mitral regurgitation (MR) have an audible murmur. 12 In asymptomatic patients with a murmur on physical examination, those with a benign flow murmur should be distinguished from those with a pathologic murmur. 13 Although there are no absolutely reliable criteria for making this distinction, a reasonable estimate of the pretest likelihood of disease can be derived from the history and physical examination findings. Flow murmurs, defined as audible systolic murmurs in the absence of structural heart disease, are most common in younger patients and those with high-output states. Thus, a flow murmur is a normal finding in pregnancy, being appreciated in more than 80% of pregnant women.5,6 Flow murmurs also are likely in patients who are anemic or febrile. Typically a flow murmur is systolic, of low intensity (grade 1 to 2) and loudest at the base with little radiation, ends before the second heart sound, and has a crescendo-decrescendo or “ejection” shape with an early systolic peak. Flow murmurs are related to rapid ejection into the aorta or pulmonary artery in patients with normal valve function, high flow rates, and good transmission of sound to the chest wall.4,14 The yield of echocardiography is very low in asymptomatic patients with a typical flow murmur on examination, no history of cardiac problems, and no cardiac symptoms on careful questioning. In contrast, echocardiographic examination usually is appropriate in asymptomatic patients with a diastolic or continuous murmur, a systolic murmur of grade 3 or higher, an ejection click or midsystolic click, a holosystolic (rather than ejection) murmur, or an atypical pattern of radiation, even if the patient is asymptomatic. To some extent, the loudness of the murmur correlates with disease severity but is not reliable for decision making in an individual patient.15,16 Echocardiography allows differentiation of valve disease from a flow murmur, identification of the specific valve involved, definition of the etiology of valve disease, and quantitation of the hemodynamic severity of the lesion along with LV size and function. On the basis of these data, the expected prognosis, need for preventive measures, and timing of subsequent examinations (if any) can be determined. In older adults, distinguishing a benign from a pathologic murmur is more difficult than in younger patients, because many older patients have some degree of aortic valve sclerosis or mild MR that can be appreciated on auscultation, and many also have mild symptoms that may or may not be related to heart disease.10,17–19 In this setting, a baseline echocardiogram may be prudent. The finding of aortic sclerosis is associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events, and some patients have progressive valve obstruction. A soft mitral regurgitant murmur is most likely associated with mild to moderate regurgitation due to mitral annular calcification, but establishing the diagnosis with a baseline echocardiogram and excluding other causes of MR, such as ischemic disease and mitral valve prolapse, is appropriate. Although echocardiography is the primary diagnostic modality used for evaluation of valve disease, cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging and computed tomography (CT) are useful in some cases, as discussed in Chapter 8. Diagnostic cardiac catheterization continues to be useful in selected patients, particularly when echocardiographic data are nondiagnostic or discrepant with other clinical data, as discussed in Chapter 7. Rheumatic fever is a multiorgan inflammatory disease that occurs 10 days to 3 weeks after group A streptococcal pharyngitis. The clinical diagnosis is based on the conjunction of an antecedent streptococcal throat infection and classic manifestations of the disease, including carditis, polyarthritis, chorea, erythema marginatum, and subcutaneous nodules.20–22 Clinical guidelines for the diagnosis of rheumatic fever allow greater specificity because many of the manifestations of rheumatic fever are seen in other conditions as well ( Table 9-3). Some studies show that strict adherence to these guidelines may result in underdiagnoses, 23 and additional echocardiographic criteria have been suggested. Although these guidelines are helpful in the initial diagnosis of rheumatic fever, exceptions do occur, so consideration of the diagnosis is of central importance in the recognition of this disease. Poststreptococcal reactive arthritis has some overlap in symptoms and signs with acute rheumatic fever but has no cardiac involvement.24,25 TABLE 9-3 Updated Jones Criteria for the Diagnosis of Initial Attacks of Rheumatic Fever Major Criteria • Carditis (may involve endocardium, myocardium, and pericardium) • Polyarthritis (most frequent manifestation, usually migratory) • Chorea (documentation of recent Group A streptococcal infection may be difficult) • Erythema marginatum (distinctive, evanescent rash on trunk and proximal extremities) • Subcutaneous nodules (firm, painless nodules on extensor surfaces of elbows, knees, and wrists) Minor Criteria • Clinical findings (arthralgia, fever) • Laboratory findings (elevation of erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein) Evidence of Antecedent Group A Streptococcal Infection High Probability of Rheumatic Fever Evidence of preceding Group A Streptococcal infection PLUS 2 major criteria OR 1 major and 2 minor criteria Modified from Guidelines for the diagnosis of rheumatic fever: Jones Criteria, 1992 update (in Circulation 1993;87:302–7) as updated in Ferrieri P. Jones Criteria Working Group. Proceedings of the Jones Criteria workshop. Circulation 2002;106:2521–153. The carditis associated with rheumatic fever is a pancarditis; there may be involvement of the pericardium, myocardium, and valvular tissue. Rheumatic disease preferentially affects the mitral valve, with MR being characteristic of the acute episode and mitral stenosis (MS) characteristic of the long-term effect of the disease process. 26 It has been suggested that echocardiography can improve the early diagnosis of rheumatic fever by detection of valvular regurgitation. 27 However, a slight degree of MR is common in normal individuals so it is not a specific finding. Primary prevention of rheumatic fever is based on treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis with appropriate antibiotics for a sufficient time. 21 Patients with a history of rheumatic fever are at high risk for recurrent disease, leading to repeated episodes of valvulitis and increased damage to the valvular apparatus. Because recurrent streptococcal infections may be asymptomatic, secondary prevention is based on the use of continuous antibiotic therapy ( Table 9-4). The risk of recurrent disease is related to the number of previous episodes, time interval since the last episode, the risk of exposure to streptococcal infections (contact with children or crowded situations), and patient age. A longer duration of secondary prevention is recommended in patients with evidence of carditis or persistent valvular disease than in those with no evidence of valvular damage. TABLE 9-4 Recommendations for Prevention of Rheumatic Fever *To be avoided in those with immediate (Type I) hypersensitivity to a penicillin. From Gerber MA, Baltimore RS, Eaton CB, et al. Prevention of rheumatic fever and diagnosis and treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the Interdisciplinary Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology, and the Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Circulation 2009;119:1541–51. Copyright © 2009 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Infective endocarditis occurs when bacteremia results in bacterial adherence and proliferation at sites of platelet and fibrin deposition on disrupted endothelial surfaces. Patients with native and prosthetic heart valve disease are at increased risk for infective endocarditis because of endothelial disruption on the valve leaflets secondary to high-velocity and turbulent blood flow patterns (see Chapter 25). About 50% of patients with endocarditis have underlying native valve disease, and endocarditis may precipitate the diagnosis of valve disease in a previously asymptomatic patient. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis is based on short-term antibiotic therapy at times of anticipated bacteremia in patients at the highest risk of endocarditis. The American Heart Association has published revised guidelines for groups of patients at highest risk ( Table 9-5), procedures likely to cause significant bacteremia ( Table 9-6), and appropriate antibiotic regimens for dental procedures ( Table 9-7). 28 Prophylaxis for other procedures should include antibiotics active against the organisms most likely to be present, as detailed in these guidelines. Antibiotics also are recommended at the time of surgical implantation of prosthetic cardiac valves or other intracardiac material. TABLE 9-5 Cardiac Conditions for which Endocarditis Prophylaxis for Dental Procedures Is Reasonable • Prosthetic cardiac valve or prosthetic material used for cardiac valve repair * • Previous infective endocarditis • Congenital heart disease (CHD) †: • Unrepaired cyanotic CHD, including palliative shunts and conduits • Completely repaired CHD with prosthetic material or device, whether placed by surgery or catheter intervention, during the first 6 months after the procedure ‡ • Repaired CHD with residual defects at the site or adjacent to the site of a prosthetic patch or prosthetic device (which inhibits endothelialization) • Cardiac transplant recipients in whom valve disease develops *Prophylaxis is not needed for patients with only coronary artery stents. †Except for the conditions listed here, antibiotic prophylaxis is no longer recommended for any form of CHD. ‡Prophylaxis is reasonable because endothelialization of prosthetic material occurs within 6 months after the procedure. Modified from Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2007;116:1736–54. TABLE 9-6 Dental or Surgical Procedures for which Endocarditis Prophylaxis Is Recommended * Prophylaxis Recommended for Patients Meeting Criteria in Table 9-5 • All dental procedures that involve manipulation of gingival tissue or the periapical region of teeth or perforation of the oral mucosa (Class IIa, LOE C) • Invasive procedures of the respiratory tract that involve incision or biopsy, including tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy (Class IIa, LOE C) • Infections of the GI or GU tract, including an antibiotic active against enterococci (Class IIb, LOE B) • Elective cystoscopy or other urinary tract manipulation only in patients with an enterococcal urinary tract infection or colonization, using an agent active against enterococci (Class IIb, LOE B) • Procedures on infected skin or musculoskeletal tissue including agents active against staphylococci and b-hemolytic streptococci (Class IIb, LOE C) Prophylaxis Recommended for ALL Patients • Surgical placement of prosthetic heart valves or prosthetic intravascular or intracardiac material, (Class I, LOE B) using a first-generation cephalosporin (Class I, LOE A) or vancomycin at centers with high prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (Class IIb, LOE C). Prophylaxis should begin immediately before surgery and should be continued for less than 48 hours (Class IIa, LOE B). Prophylaxis Solely to Prevent Endocarditis NOT Needed Minor Dental Procedures • Routine anesthetic injections through noninfected tissue • Placement, removal, or adjustment of prosthodontic or orthodontic appliances • Placement of orthodontic brackets Respiratory Procedure GU and GI Procedures Skin and Musculoskeletal Procedures GI, gastrointestinal; GU, genitourinary; LOE, level of evidence. *ACC/AHA classification of recommendations (I, IIa, IIb) and level of evidence (A, B, C) are used (see Appendix A). Summarized from Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2007;116:1736–54. TABLE 9-7 American Heart Association Recommendations for Endocarditis Prophylaxis for Dental Procedures IM, intramuscularly; IV, intravenously. *Or other first- or second-generation oral cephalosporin in equivalent adult or pediatric dosage. †Cephalosporins should not be used in individuals with anaphylaxis, angioedema, or urticaria penicillin or ampicillin. From Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2007;116:1736–54. On the basis of a careful review of the published literature and expert opinion, current guidelines no longer recommend endocarditis prophylaxis for patients with native valvular heart disease. 28 The key elements underlying the current recommendations are: (1) the recognition that bacteremia due to normal daily activities, like tooth brushing, flossing, and chewing, is much more frequent than bacteremia related to dental procedures, (2) there are no controlled studies showing that short-term antibiotic therapy at the time of anticipated bacteremia prevents endocarditis, and estimates of total benefit are exceedingly small, (3) the risk of an adverse reaction to the antibiotic outweighs any potential benefit, and (4) the most important factor in reducing daily bacteremia is maintaining optimal oral health and hygiene, including regular dental care.29,30 Analysis of large data sets from the United Kingdom and United States showed that the current recommendations have resulted in an approximately 80% decrease in the use of antibiotic prophylaxis with no evidence of an increase in endocarditis cases.31,32 Prevention of embolic events in patients with valvular heart disease, particularly those with prosthetic valves, MS, or AF, is a key component of optimal medical therapy7,33–38 ( Table 9-8). While anticoagulation in patients with prosthetic valves is discussed in Chapter 26, this section discusses anticoagulation in adults with native valve disease. A systemic embolic event can have devastating consequences and may occur even in previously asymptomatic patients. Systemic embolism is usually due to left atrial (LA) thrombus formation in patients with low blood flow in a dilated LA chamber, with or without concurrent AF ( Figure 9-2).39–44 Embolic events due to calcific debris from the aortic or mitral valves are much less common but may occur when a catheter is passed across the aortic valve.45–47 TABLE 9-8 Recommendations for Anticoagulation in Patients with Native Valvular Heart Disease *This recommendation is not based on guidelines but is based on review of references 7, 33–37, and 115. FIGURE 9-2 Left atrial spontaneous contrast. Therapy for prevention of embolic events in patients with valvular heart disease typically includes antiplatelet agents or long-term warfarin anticoagulation. There is little data on the use of newer anticoagulants, such as direct thrombin inhibitors and anti-Xa agents, for prevention of embolic events in patients with valve disease. In patients with mechanical prosthetic valves, these newer agents should not be used because of (1) a higher incidence of thromboembolic events in several case reports involving such patients and (2) early termination of RE-ALIGN (Randomized, phase II study to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics of oral dabigatran etexilate in patients after heart valve replacement) owing to a higher rate of valve thrombosis, stroke, and myocardial infarction in subjects randomly assigned to dabigatran compared to those receiving warfarin.48–50 These findings prompted a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) “black box” warning on the package insert for dabigatran against its use in patients with mechanical heart valves. 51 In addition, patients with AF associated with rheumatic mitral valve disease are at much higher risk for embolic events than those without valve disease, so the current expert clinical consensus is to use warfarin in patients with rheumatic mitral valve disease and indications for anticoagulation. However, the choice of warfarin or newer agents in patients with AF and aortic valve disease or nonrheumatic mitral valve disease is less clear, and most experts believe that these patients should be treated by following the same guidelines as in patients without valve disease, particularly if valve disease is only mild or moderate in severity.52,53

Basic Principles of Medical Therapy in the Patient with Valvular Heart Disease

The Heart Valve Clinic

CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; CT, computed tomography; Echo, echocardiography; VHD, valvular heart disease. (From Lancellotti P, Rosenhek R, Pibarot P, et al. ESC Working Group on Valvular Heart Disease Position Paper—heart valve clinics: organization, structure, and experiences. Eur Heart J 2013;Jan 4. [Epub ahead of print])

Diagnosis of Valve Disease

Preventive Measures

Diagnosis and Prevention of Rheumatic Fever

Prevention of Infective Endocarditis

Prevention of Embolic Events

VALVE LESION

RECOMMENDATION

Mitral valve disease with AF

Warfarin, INR 2.0-3.0

Rheumatic mitral valve stenosis:

Paroxysmal, persistent or permanent AF

Warfarin, INR 2.0-3.0

Previous embolic event or LA thrombus (even with NSR)

Warfarin, INR 2.0-3.0

Recurrent systemic emboli despite adequate anticoagulation

Add aspirin 80-100 mg qd OR

dipyridamole 400 mg qd OR

ticlopidine 250 mg bid

Mitral valve prolapse:

TIAs

Long-term (75-325 mg qd) aspirin

AF and age <65 years with no other risk factors

Long-term (75-325 mg qd) aspirin

AF plus at least 1 other risk factor (age > 65 years, hypertension, MR murmur, or history of HF)

Warfarin, INR 2.0-3.0

CVA with AF, MR, or LA thrombus

Warfarin, INR 2.0-3.0

Infective endocarditis:

Native valve or tissue prosthesis

Anticoagulation therapy contraindicated

Mechanical valve

Continue or restart anticoagulation (heparin or warfarin) when neurologic condition allows

Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis: *

With systemic emboli

Heparin anticoagulation

Debilitating disease with aseptic vegetations on echocardiography

Heparin anticoagulation

Transesophageal imaging in a patient with rheumatic mitral stenosis shows diffuse mobile echodensities in the left atrium consistent with blood flow stasis. Arrow indicates the left atrial appendage with a possible thrombus. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle. (From Otto CM. Textbook of clinical echocardiography. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2013.)

Choice of Antithrombotic Therapy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basic Principles of Medical Therapy in the Patient with Valvular Heart Disease

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue