Definitions, incidence and natural history

Stroke and non-central nervous system (CNS) embolism have long been known to be important complications of atrial fibrillation (AF). In several case series, 50–70% of embolic strokes were found to result in either death or severe neurologic deficit.1 The Framingham Study2,3 documented an annual 4.5% incidence of stroke among individuals with rheumatic AF, although those with AF in the absence of other disease and whose age is under 60 years (so-called “lone atrial fibrillation”) have an extremely low risk of stroke.4,5 The terms “non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation” and “non-valvular atrial fibrillation” (NVAF) are not entirely synonymous, although they are often used interchangeably. Non-valvular atrial fibrillation has become the preferred term for patients with AF in the absence of mitral valve disease, a prosthetic valve or mitral valve repair.6 Paroxysmal AF is defined as an episode lasting up to seven days, whereas persistent AF is defined as a duration beyond seven days. Both paroxysmal and persistent AF are designated as recurrent AF if they resolve spontaneously or in response to treatment and then recur. Persistent AF is defined as permanent if cardioversion fails or AF lasts for more than one year and cardioversion has not been attempted.

Data from the placebo groups of five landmark randomized clinical trials among patients with non-valvular AF7–12 found a mean 4.5% annual incidence of stroke (range 3–7%) and a mean 5.0% annual incidence of stroke plus other systemic emboli (range 3–7.4%); over half the strokes resulted in death or permanent disability.13 Patients were selected for entry into these trials according to a variety of criteria, including the absence of contraindications to warfarin and in some instances to aspirin, willingness to participate in a clinical trial and the echocardiographic exclusion of rheumatic valvular disease. Although generalizations to a wider population must be made cautiously, the observed rates of stroke and other systemic embolism are similar to those reported in earlier cohorts and likely are representative of those in the general population.

Oral anticoagulant therapy

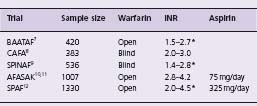

Prior to 1990, anticoagulation was usually prescribed for AF patients who had mitral stenosis, a prosthetic heart valve, prior arterial embolism or who were to undergo electrical cardioversion. Anticoagulation was generally not prescribed long-term for patients with non-rheumatic AF. In the late 1980s, the observations of the Framingham Study, together with evidence for the efficacy and increased safety of regimens of lower-dose warfarin, prompted the initiation of five randomized controlled trials of warfarin versus control or placebo for the primary prevention of thromboembolism among patients with non-rheumatic (non-valvular) AF (Table 37.1).13 The trials enrolled patients with AF detected on a routine or screening electrocardiogram, whose mean age was 69 years. AFASAK10 and SPINAF9 excluded patients with intermittent AF, whereas the proportion of intermittent AF in CAFA8 was 7%, in BAATAF7 16% and in SPAF12 34%. Previous stroke or transient ischemic attack was infrequent. Treatment allocation was randomized in all trials; the international normalized ratio (INR) ranges varied from a lower limit of 1.4 to an upper limit of 4.5. There was a double-blind comparison of warfarin to placebo in CAFA and SPINAF, and an open-label comparison in BAATAF. AFASAK compared warfarin, aspirin and aspirin placebo. SPAF allocated patients as being warfarin eligible (group 1) or warfarin ineligible (group 2). Group 1 patients were randomized to open-label warfarin, aspirin 325 mg/day or aspirin placebo; group 2 patients were randomized to aspirin or aspirin placebo.

Table 37.1 Non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation: designs of randomized trials

AFASAK, Copenhagen Atrial Fibrillation Aspirin Anticoagulation; BAATAF, Boston Area Anticoagulation Trial for Atrial Fibrillation; CAFA, Canadian Atrial Fibrillation Anticoagulation; INR, international normalized ratio; SPAF, Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation; SPINAF, Stroke Prevention in Non-rheumatic Atrial Fibrillation

* INRs estimated by investigators from prothrombin time ratios.

Four of the trials7,9,10,12 were stopped early by their Data and Safety Monitoring Boards (DSMB) because interim analyses were strongly positive, whereas the fifth8 was stopped early because of the strongly positive results from two other trials. The primary outcomes varied somewhat among the trials. However, it is possible to determine the rates of ischemic stroke and major bleeding (intracranial, transfusion of two or more units, hospitalization) from each trial, to make comparisons and to pool the results. The Atrial Fibrillation Investigators overview13 was a collaborative prospective meta-analysis which provides reliable summary data based on individual patient information. The overall risk of ischemic stroke of 4.5% per year (identical to that documented in the Framingham Study) was reduced to 1.4% per year with warfarin, a relative risk reduction (RRR) of 68% (95% confidence interval (CI) 50–79%) and an absolute reduction of 31 strokes for every 1000 patients treated (P < 0.001). A major concern with warfarin is hemorrhage, which was carefully documented in each trial. The rate of major hemorrhage with warfarin was 1.3% per year versus 1% per year in controls, an increase of three major hemorrhages per 1000 patients treated, including an excess of intracranial hemorrhage of two per year for every 1000 patients treated. A more recent meta-analysis14 of these five trials calculated a RRR of 66% for ischemic stroke, and 61% for ischemic stroke or intracranial hemorrhage. This overview calculated a significant 31% RRR of all-cause mortality. Hence, the overall picture is one of major benefit from warfarin, with only a modest and statistically insignificant increase in the risk of major extracranial hemorrhage and cerebral hemorrhage (Level A).

The European Atrial Fibrillation Trial (EAFT) compared oral anticoagulants, aspirin and placebo in patients with non-rheumatic AF who had experienced a transient isch-emic attack (TIA) or stroke within the preceding three months.15 The annual risk of recurrence was 12% among the placebo patients, dramatically higher than the 4.5% annual risk in the overall population of patients with non-rheumatic AF. The relative risk reduction by anticoagulants was 66% (P < 0.001), virtually identical to that calculated in the overview of the five major randomized controlled trials, but the absolute reduction of strokes was much greater (84 per year per 1000 patients) because of the high baseline risk of stroke in this population. Major extracranial bleeding was more frequent on anticoagulants versus placebo (excess of 21 per year per 1000), but this adverse event was far outweighed by the reduction of major or moderately disabling strokes by anticoagulants (Level A).

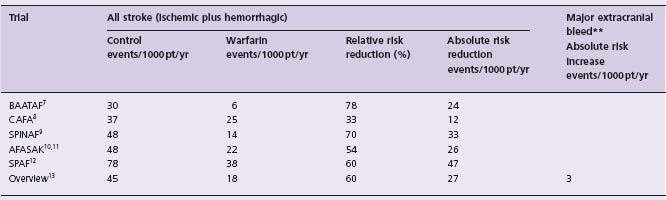

A recent meta-anlysis16 of primary and secondary prevention trials has assessed the outcome of all stroke (ischemic plus hemorrhagic), providing a more clinically meaningful summary than the outcome of ischemic stroke only. The relative risk reduction was 64% overall, about 60% in primary prevention trials (absolute risk reduction [ARR] was 27/1000 patients/year) (Table 37.2) and about 68% for secondary prevention (ARR 84/1000 patients/ year). There was an excess of major extracranial bleeding of 3/1000 patients/year with adjusted dose oral anticoagu-lation versus control.

Table 37.2 Non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation: outcomes of primary prevention randomized trials of warfarin*

*Data from Hart et al16

**Major bleed defined as a bleeding event requiring 2 U of blood or requiring hospital admission.

Aspirin therapy

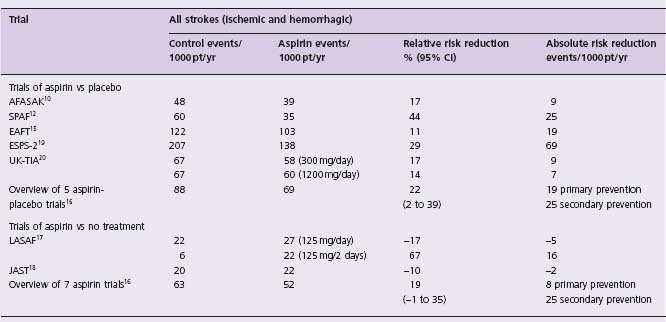

Comparisons of aspirin and placebo resulted in a somewhat less impressive risk reduction for stroke of about 16% (NS) in AFASAK,10 44% (P = 0.02) in SPAF12 and 17% (NS) in the European Atrial Fibrillation Trial (EAFT)15 (Table 37.3). A recently updated meta-analysis16 which included the Low Dose Aspirin, Stroke and Atrial Fibrillation pilot study (LASAF),17 the Japan Atrial Fibrillation Stroke Trial,18 atrial fibrillation patients from the European Stroke Prevention Study 2 (ESPS-2)19 and the United Kingdom TIA Study (UK-TIA)20 found a statistically significant 22% RRR (95% CI 2–39%) of all strokes (ischemic plus hemorrhagic) in five trials of aspirin versus placebo, and a 19% RRR (95% CI 1–35%) when two trials of aspirin versus no treatment were included. The ARR was 0.8%/year in primary prevention trials and 2.5%/year in secondary prevention trials. Hence, aspirin can be expected to reduce the risk of ischemic stroke and all strokes, with an ARR of about one half that of warfarin and with a somewhat lower risk of major extracranial bleeding of 0.2%/year versus 0.3%/year (Level A).

Table 37.3 Non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation: outcomes of primary and secondary prevention randomized trials of aspirin

*Data from Hart et al16

Aspirin versus oral anticoagulants

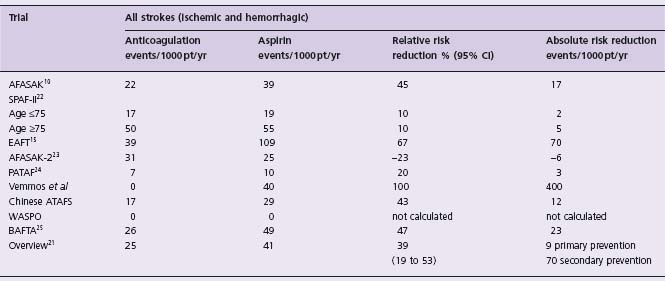

Direct comparisons of oral anticoagulants and aspirin have been undertaken in nine trials16,21 (Table 37.4). AFASAK10 included 671 patients who were randomized to warfarin (INR 2.8 –4.2) or aspirin 75mg/day. SPAF-II22 studied 715 patients aged 75 years or less and 385 patients aged over 75 years, with each group randomly allocated to either warfarin (INR 2.0–4.5) or aspirin (325 mg/day). EAFT15 randomized 455 anticoagulation-eligible patients with recent TIA or minor ischemic stroke to oral anticoagulant (INR 2.5–4.0) or aspirin (300mg/day). AFASAK-223 randomized 339 patients into a primary prevention trial which compared warfarin (INR 2–3) to aspirin (300 mg/day). PATAF24 randomized 272 patients into a primary prevention trial which compared warfarin (INR 2.5 –3.5) to aspirin (150mg/day). A meta-analysis16 and an update21 found a statistically significant 39% (95% CI 19–53) RRR of all strokes (ischemic plus hemorrhagic) with anticoagulants, equivalent to an ARR of about 9 events/1000 patients/year for primary prevention and 70 events/1000 patients/year for secondary prevention (Level A). Major extracranial hemorrhage occurred with an excess of about 2/1000/year on warfarin.16

Table 37.4 Non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation: outcomes of primary and secondary randomized trials of adjusted dose anticoagulation vs aspirin*

*Data from Hart et al16,21

In SPAF II warfarin was superior to aspirin for reducing ischemic stroke, but the risk of intracranial hemorrhage was increased with warfarin, particularly in patients >75 years of age. When patients of all ages were considered, there was an ARR of 0.8%/year (P = NS) in ischemic stroke or systemic embolus with warfarin, but when all strokes were compared, the ARR was only 0.3%/year (P = NS). The relatively high rates of intracranial bleeding may be attributable to the use of prothrombin time monitoring, the high INR range chosen and the very elderly population. If the SPAF II results were to be excluded from the meta-analysis, the RRR of all strokes (ischemic and hemorrhagic) with anticoagulation would be greater than 39%.

The Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged (BAFTA) Trial25 was a randomized, open-label study of warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) versus aspirin (75 mg/day) which is particularly relevant to several areas of uncertainty in current practice, because the patients were aged 75 years and greater (mean 81.5 years). They were recruited from and managed within general practices in England and Wales and the primary outcome included fatal or disabling stroke (ischemic and hemorrhagic), intracranial hemorrhage, and clinically significant arterial embolism. Warfarin reduced the annual risk of the primary outcome from 3.8% to 1.8%, a RRR of 52% (P = 0.003), and an ARR of 2% per year. The annual risk of extracranial hemorrhage was 1.4% (warfarin) versus 1.6% (aspirin). It should be noted that 40% of patients were on warfarin prior to study entry and that the study subjects represented only an estimated 10% of those with AF in the geographic region. Nevertheless, the results provide powerful evidence for the relative efficacy and safety of warfarin over aspirin for the treatment of NVAF in carefully selected elderly patients in real-life clinical practice settings.

Adjusted Dose Anticoagulation compared to warfarin/ aspirin combinations, low or fixed dose anticoagulation, and to alternative antiplatelet regimens

The SPAF III trial26 was undertaken in an attempt to reduce the rates of major hemorrhage with warfarin, while improving on the stroke prevention achievable by aspirin alone. Patients at high risk of embolic stroke (at least one of impaired LV function, systolic hypertension, prior thromboembolism, or female gender plus age over 75 years) were randomly allocated warfarin 1–3mg/day plus aspirin 325 mg/day or warfarin (INR 2–3). The trial was discontinued early after a mean follow-up of 1.2 years, because the rate of the composite primary outcome of ischemic stroke or systemic embolus was significantly higher in those given combination therapy than in those given adjusted-dose warfarin (7.9% vs 1.9% per year, P < 0.0001). Rates of disabling stroke and of the composite of ischemic stroke, systemic embolus or vascular death were also significantly and markedly increased. The rates of major bleeding were similar in the two treatment groups.

AFASAK 222 was designed to compare regimens of aspirin 300mg/day, fixed-dose warfarin (1.25mg/day) plus aspirin 300 mg/day and fixed-dose warfarin 1.25mg/ day to warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0). The trial was stopped early when the results of SPAF III became available. Adjusted-dose warfarin was superior to each of the three comparison regimens at this point. It is clear that in high-risk patients, regimens of low fixed-dose warfarin in combination with aspirin do not provide adequate protection against thromboembolism (Level A).

Three trials (AFASAK 2,22 MWNAF27 and PATAF23) compared low or fixed doses of warfarin with standard warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0 or 2.5–3.5) but none showed a benefit. A meta-analysis24 calculated a statistically insignificant 38% RRR for all strokes with the adjusted-dose warfarin (Level A).

The SIFA study28 compared the antiplatelet agent indo-bufen to warfarin (INR 2.0–3.5), randomizing 916 patients with recent ischemic stroke or TIA. During a one-year follow-up, the RRR by warfarin was 21% (95% CI 54–60%) (Level A).

The FFAACS29 study compared the oral anticoagulant fluindione (INR 2.0–2.6) to fluindione plus aspirin 100 mg/ day in high-risk patients with AF, but was stopped early because of excess hemorrhage in the combination group. The NAS-PAEF study30 randomized 495 high-risk AF patients to acencoumarol (INR 2.0–3.0) or acencoumarol (INR 1.4–2.4) plus the cyclo-oxygenase inhibitor triflusal (600 mg/day). There were 714 lower risk patients randomized to acencoumarol (INR 2.0–3.0), triflusal or triflusal plus acencoumarol (INR 1.25–2.0). The achieved INRs differed less than was intended between the acencoumarol alone group (mean INR 2.5) and the combination therapy groups (mean INRs 1.93 and 2.17 in the low-and high-risk strata, respectively). The hazard ratio (HR) of the combination versus acencoumarol alone for the outcome of isch-emic stroke or systemic embolus was 0.44 in both groups. When severe bleeding was combined with the primary outcome of vascular death, TIA or non-fatal stroke, there was an ARR of 2.3%/year (P < 0.05) with the combination in the intermediate risk group and an ARR of 1.74%/year (P = NS) in the high-risk group (Level B). These results suggest that it may yet be possible to find a regimen of antiplatelet agent and lower dose anticoagulant, but the appropriate INR range is likely to be only marginally less than the standard 2.0–3.0.

The ACTIVE program comprised three separate interrelated trials, including ACTIVE-W,31 which used a non-inferiority design to compare the combination of clopidogrel (75mg/day) plus aspirin (recommended at 75–100mg/ day) to anticoagulation (INR 2.0–3.0), among patients with AF who were eligible and willing to take anticoagulation. The trial was stopped early (only 27% of expected events had occurred) at the recommendation of the DSMB, because of an extremely low likelihood of eventually concluding non-inferiority of the clopidogrel/aspirin combination. Among the 6706 patients enrolled and followed for a median of 1.28 years, the risk ratio with the combination for the composite outcome of stroke, non-CNS embolus, myocardial infarction and vascular death was 1.44 (95% CI 1.18–1.76, P = 0.0003), and for all stroke was 1.72 (95% CI 1.24–4.37, P = 0.002) (Level A). Somewhat surprisingly, the risk ratio for major bleeding was 1.10 (95% CI 0.83–1.45) with the combination.

The ACTIVE-A trial31a compared the combination of clopidogrel (75 mg/day) plus aspirin to aspirin alone among 7554 patients with AF at increased risk of stroke and for whom vitamin K antagonist therapy was unsuitable. After a mean 3.6 years the risk of major vascular events was reduced by the combination (RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.81, 0.98; P = 0.01). However, major bleeding was increased (2.0% vs 1.3%/year, RR 1.57; 95% CI 1.29, 1.92; P < 0.001).

Other anticoagulants

Warfarin and other vitamin K antagonists are very effective in reducing the incidence of stroke and systemic embolus. However, the narrow therapeutic margin and the interactions with many other drugs and foods necessitate frequent monitoring and patient diligence. There is a substantial risk of major hemorrhage, particularly in elderly patients. Ximelagatran is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor, with predictable and stable pharmacokinetics and relatively low potential for interactions with other drugs and with foods. Coagulation monitoring and dose adjustments are not required. This agent was evaluated in two large trials employing non-inferiority designs.32,.33 In both, it was concluded that ximelagatran was non-inferior (i.e. not unacceptably inferior) to warfarin.

SPORTIF III32 randomized 3410 patients with AF and one or more stroke risk factors to open-label warfarin (INR 2.0–3.0) or ximelagatran (36 mg bid). During a mean 17.4-month follow-up, the incidence of the primary outcome (all stroke or systemic embolus) by intention to treat was reduced to 1.6%/year with ximelagatran from 2.3%/year with warfarin (ARR 0.7%/year, 95% CI–0.1–1.4%, P = 0.10 and RRR 29%, 95% CI–6.5–52%). The incidence of major bleeding was similar in the two groups, but the total of minor or major bleeding was less frequent with ximelaga-tran (25.8%/year vs 29.8%/year, RRR 14%, 95% CI 4–22%, P = 0.007). The authors concluded that ximelagatran was “at least as effective” as warfarin for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism.

SPORTIF V33 compared ximelagatran to warfarin among 3922 patients in a study of almost identical design, except that it was double blind. During a mean follow-up of 20 months, the incidence of the primary outcome was 1.6%/ year with ximelagatran and 1.2%/year with warfarin (ARR –0.45%/year, 95% CI –1.0–0.13%/year, but P < 0.001 for the predefined non-inferiority margin). The incidence of major bleeding was similar in the two groups, whereas major or minor bleeding was less frequent with ximelagatran (37% vs 47%/year, 95% CI–14% to–6.0%/year, P < 0.001). The authors concluded that “ximelagatran was non-inferior to well-controlled warfarin”.

Both studies found an excess of patients with elevations of alanine transaminase (ALT) to greater than three times the upper limit of normal, usually within the first six months (6.0% vs 1% in SPORTIF III and 6.0% vs 0.8% in SPORTIF V). Furthermore, the claim of non-inferiority was based on the choice of non-inferiority margins that were excessive.34 The commonly accepted approach is to estimate the efficacy of the currently accepted therapy (in this case warfarin vs placebo) from a meta-analysis and then to choose a non-inferiority margin which would represent preservation of at least 50% of the benefit of the accepted therapy compared to placebo. If the non-inferiority margin had been chosen according to the FDA recommendations, SPORTIF III would still have reached a conclusion of non-inferiority, but SPORTIF V would not, nor would a meta-analysis of the two studies. The FDA did not approve the new agent, having concluded that the more convenient dose and monitoring regimens and less total bleeding did not outweigh their concerns about hepa tic toxicity and the appropriateness of the chosen non-inferiority margins (Level B).

Dabigatran is another oral direct thrombin inhibitor which is being compared to warfarin (INR 2-3) among patients with AF with at least one additional risk factor for stoke in the RE-LY trial. Enrollment is complete (18 113 patients) and results are expected in 2009.

There are several available oral, direct acting Factor Xa inhibitor drugs which have proven effective and safe in studies of deep venous thrombosis and offer promise in the setting of AF. In the AVERROES trial, apixaban (5 mg bid) is being compared to aspirin (81–324mg daily) among patients with AF at more than very low risk of stroke in whom vitamin K antagonist therapy is unsuitable. The expected enrollment is 5600 patients with completion in 2010. In the ARISTOTLE trial, apixaban (5 mg bid) is being compared to warfarin (INR 2.5) among patients with AF at somewhat higher risk of stroke. The expected enrollment is 15 000 patients with completion in 2010. In the ROCKET AF trial, rivaroxaban (20 mg/day) is being compared to warfarin (INR 2.5) among patients with AF at risk of stroke and suitable for warfarin therapy. The expected enrollment is 14 000 patients with completion in 2010. In the ENGAGE AF TIMI 48 trial, DU-176b (high and low dose regimens) is being compared to warfarin among patients with AF at risk of stroke and suitable for warfarin therapy. The expected enrollment is 16 500 patients with completion in 2011.

Risk stratification (stroke or systemic embolus)

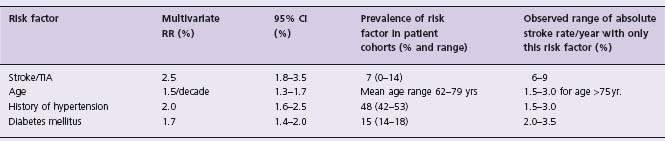

Rigorous and current data for stroke risk come from analyses of the placebo patients in large clinical trials of antithrombotic therapy. The Atrial Fibrillation Investigators overview13 calculated the annual risk of stroke to be 4.5% among the total group of control patients in the five major primary prevention randomized trials of anticoagulation. The statistically significant multivariate predictors of stroke were previous stroke or TIA, increasing age, history of hypertension, and diabetes. Annual stroke risk ranged from 0 (112 patients < 60 years age) to 1.3% (patients <80 years age with no other risk factors), to 11.7% (patients with prior stroke or TIA). A recent systematic review35 examined the evidence identifying independent risk factors for stroke as reported in seven studies (including the AFIoverview13) selected according to rigorously defined criteria. The absolute annual risk of stroke varied 20-fold among patients grouped by various risk factors. Independent risk factors for stroke (Table 37.5) were the same as those previously identified13: stroke/TIA (RR 2.5), age (RR 1.5/ decade), history of hypertension (RR 2.0) and diabetes mellitus (RR 1.7). Female sex was an independent risk factor in three of six cohorts, but coronary artery disease and clinical congestive heart failure were not found to be independent risk factors in any of the studies which met the inclusion criteria. Congestive heart failure and reduced ejection fraction have been identified as univariant risk factors13,36,37 and are included in current risk classification schemes.6,38 The review emphasized a variety of shortcomings of the studies, including inconsistencies in definitions of some of the risk factors, the use of antiplatelet therapies, and the stroke outcomes (ischemic strokes only, all strokes, strokes plus other systemic emboli and strokes plus TIAs) (Level A).

Table 37.5 Risk factors for stroke in patients with non-vascular atrial fibrillation*

*Data from Stroke Risk in Atrial Fibrillation Working Group35

RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval

The data from the Atrial Fibrillation Investigators overview13 and the SPAF group35 were combined to create the CHADS2 index38 which assigns 1 point each for congestive heart failure, hypertension, age 75 years or older and diabetes mellitus and 2 points for a history of stroke or TIA. The scheme was validated and compared to the other two schemes among 1733 Medicare beneficiaries aged 65–95 years, who had been discharged from hospital with non-rheumatic AF and not prescribed warfarin. The CHADS2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree