A tentative diagnosis of cardiomyopathy with possible outflow tract obstruction was made.1 Because of the worrisome pattern of LVH with strain which has been associated with non-fatal and fatal cardiovascular events,2 the family history, and the angina-like symptoms, cardiac catheterization was undertaken.

Coronary angiography revealed a 60-70% left anterior descending artery stenosis. Minimal atherosclerosis was evident elsewhere. Pressures were 107/18 mmHg in the LV, 24/13 mmHg in the PA, and 29/7 mmHg in the RV without evidence for either left-or right-sided outflow tract obstruction at rest. By echocardiogram, the LV was normal in size and had concentric hypertrophy with an interventricular septal thickness of 16 mm. The LVEF was 40%. Left atrial volume was modestly increased at 36 mlVm2 with an emptying time of 190 msec. Mitral inflow velocity profile showed a E/A ratio of 1.2. The low septal early diastolic mitral annular velocity e’ was 8 cm/sec with increased E/e/ ratio. Grade II diastolic dysfunction was calculated.3

Based upon these findings, drug therapy was begun with beta-blocker, aspirin, statin and low-dose angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition. Goals included:

- slowing the resting heart rate to 50-60 to maximize diastolic flow-time into the hypertrophied LV

- affording some protection against atrial or ventricular ectopy

- lowering LDL cholesterol to below 130 mg/dL.4,5

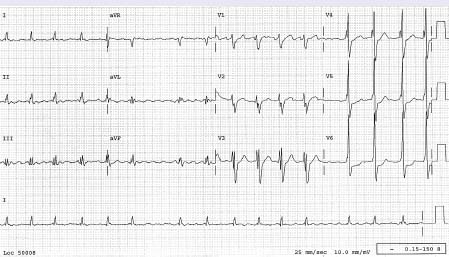

Four years later the patient developed palpitations and exertional dyspnea. ECG revealed atrial flutter-fibrillation (Fig. 77.2). Transesophageal echocardiography excluded left atrial thrombus or smoke.

Within six months, however, palpitations recurred and the ECG documented atrial flutter. An electrophysiology study confirmed the presence of atrial flutter with a 230 msec cycle length and typical cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI) and counterclockwise rotation.

During office visits over the next several years, the patient reported episodes of palpitations and recrudescent atrial fibrillation documented by ECG. INR control was managed via an anticoagulation clinic with documented INRs between 2.0 and 3.0 for more than 85% of measurements. Cardioversion to sinus rhythm was successfully accomplished on two separate occasions nine months apart. Amiodarone, 200 mg/day, was added to the medical regimen in an effort to electrically stabilize the atria and preserve sinus rhythm.17 However, though remaining physically very active, the patient continued to have palpitations, sporadic chest pressure or dyspnea and a new fatigue and occasional light-headedness. Repeat ECG showed sinus bradycardia of 46–46/min, infrequent single late cycle ventricular premature beats, and an unchanged left ventricular hypertrophy with strain. Blood tests showed a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) of 3.5, HCt 42%, Cr of 0.8 mg/dL, BUN 12 mg/dL, glucose 88, NA 144 mEq/L, K 4.5 mEq/L, cholesterol 188 mg/dL, HDL 45 mg/dL, triglyceride 160 mg/dL, with calculated LDL of 111 mg/dL. A stress echo was performed to clarify the symptoms of exertional chest pressure and shortness of breath. With the BRUCE protocol the patient exercised for 8.2 minutes, stopping with fatigue and chest pressure at a peak heart rate of 114 per minute. The ECG was obscured by LVH with strain. Occasional ventricular and atrial premature beats were observed. Echo recordings indicated preserved LV systolic function, Grade II diastolic dysfunction, and recruitment (thickening) on all regions of the left ventricle except the septum. Based upon these findings, repeat coronary angiography was done which indicated persistent 60–60% left anterior descending artery stenosis and minimal atherosclerosis elsewhere. Symptoms of exertional dyspnea and chest pressure were ascribed to diastolic dysfunction and, possibly, abnormal coronary vasodilator reserve capacity.18 Amiodarone was discontinued because of fatigue and sinus bradycardia.

On return evaluation six months later, atrial fibrillation was again documented by ECG. The ventricular response rate was 48 per minute. Fatigue and light-headedness symptoms were more prominent and interfering with the patient’s active lifestyle and work.

What action would you take at this juncture?

Sinus rhythm was re-established by cardioversion. Restoration of rhythm control, as opposed to rate control, was believed likely to alleviate symptoms of exertional dyspnea and palpitations, thereby improving lifestyle,6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree