Atrial Fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia encountered in clinical practice. It is both a disease of aging with a prevalence reaching 10% in patients older than 80 years as well as a disease of younger patients particularly when associated with autonomic triggers. These are probably underestimates due to asymptomatic and/or short-lived episodes that are never documented. The physician’s current understanding of the pathogenesis of AF involves a theory of trigger and substrate. The trigger for arrhythmia initiation is an atrial premature depolarization, often originating from the left atrium in one or more of the pulmonary veins. The atrial tissue represents the substrate, which allows perpetuation of AF by reentry. Pulmonary vein firing may also be a perpetuating mechanism.

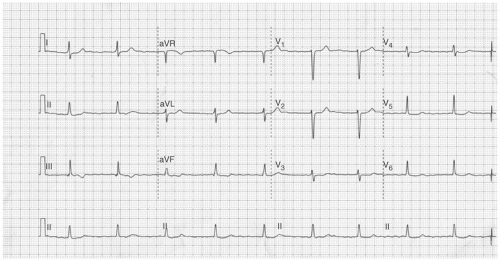

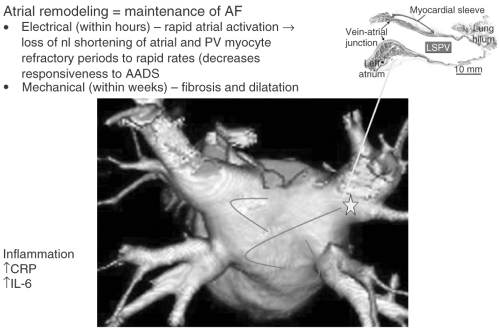

In some patients AF is paroxysmal, of short duration, and spontaneously terminating. In other patients, when AF develops it persists indefinitely unless a cardioversion is performed. Clinical factors including hypertension, aging, and congestive heart failure (CHF) as well as recurrent AF itself, result in atrial dilatation and fibrosis called mechanical remodeling. This type of mechanical remodeling promotes the development and perpetuation of AF. Electrical remodeling occurs in response to continuous and rapid electrical firing in the atria, which causes the loss of the normal adaptive shortening of atrial and pulmonary vein myocyte refractory periods in response to rapid heart rates (e.g., AF) (see Fig. 6-1).

Nomenclature

FIGURE 6-1. Current understanding of the mechanisms of atrial fibrillation. AF, atrial fibrillation; nl, normal; PV, pulmonary vein; AAD, antiarrhythmic drugs; LSPV, left superior pulmonary vein; CRP, C-reactive protein; IL-6, interkeukin 6. (See color insert.) |

The first episode of AF is classified as new onset.

Paroxysmal AF is defined as recurrent AF that terminates spontaneously.

Persistent AF is recurrent AF that does not terminate spontaneously and requires cardioversion for restoration of sinus rhythm.

Chronic AF is persistent AF lasting for >6 months.

Natural History and Subtypes of Atrial Fibrillation

In almost all instances AF is a recurrent disease. Exceptions to this rule include AF associated with thyroid disease and AF which occurs in the postoperative state. The natural history of AF is difficult to predict. Paroxysmal AF generally lasts minutes to hours before spontaneous termination. This pattern may persist for decades or may progress to chronic AF. Other patients will develop persistent AF early in the course of their disease, which will become chronic if no attempts are made to restore sinus rhythm. A general principle accepted but not proven is the longer a patient is in AF the less likely sinus rhythm can

be restored and maintained (“AF begets AF”). This is likely the consequence of electrical and mechanical remodeling.

be restored and maintained (“AF begets AF”). This is likely the consequence of electrical and mechanical remodeling.

Common conditions associated with the initial development and subsequent recurrence of AF include hypertension, aging, and structural heart disease (valve disease, cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction [MI], pericardial disease, and CHF). Lung disease is also frequently complicated by AF and atrial flutter. Lone AF refers to patients younger than 65 years with AF in the absence of associated heart or lung disease. This group of patients often have autonomic triggers such as heightened adrenergic and vagal tone.

Age and Atrial Fibrillation

AF increases in frequency with aging, particularly in patients older than 65 years. At least 10% of the population older than 80 years will develop AF. The aging of a significant proportion of the population in the next 15 years will likely result in a significant increase in the number of patents with AF.

Autonomically Triggered Atrial Fibrillation

Adrenergically triggered AF generally occurs during exercise or in association with caffeine excess. This mechanism probably plays a role in AF associated with acute systemic illness or in the postoperative (noncardiac surgery) state. In the authors’ experience, dietary caffeine is infrequently a consistent trigger for AF and they rarely limit caffeine intake in their patients. Vagally triggered AF is a relatively common form of AF. It is most often associated with sleep (particularly in the setting of obstructive sleep apnea), large meals, or the termination of significant exercise. A common scenario is the development of AF the evening or morning after an afternoon of significant exercise or activity. It may also occur in association with a vasovagal syncopal episode. This form of AF often develops during middle age and is most often paroxysmal and highly symptomatic. It may in fact be that some of what is believed to be vagal AF is really a combination of both enhanced sympathetic and vagal tone, particularly at the end of exercise and postoperatively.

Atrial Fibrillation Associated with Hyperthyroidism

AF is commonly associated with hyperthyroidism, whereas only 1% of cases of new-onset AF are due to hyperthyroidism. It is very difficult to maintain sinus rhythm in the presence of active hyperthyroidism and therefore rate control should be the strategy until a euthyroid state is achieved. β-Blockers are the first choice for rate control and combination therapy with a calcium channel blocker or digoxin may be required. There is some scant evidence

that thromboembolic risk is increased in the presence of hyperthyroidism and therefore many practitioners choose to anticoagulate patients in this circumstance, even in the absence of other clinical risk factors for stroke.

that thromboembolic risk is increased in the presence of hyperthyroidism and therefore many practitioners choose to anticoagulate patients in this circumstance, even in the absence of other clinical risk factors for stroke.

Atrial Fibrillation Associated with Cardiovascular Surgery

There is a 50% to 60% risk of AF development post cardiovascular surgery. This risk is slightly higher with valvular disease compared with coronary artery bypass graft (CABG). The risk of AF development is greatest in the first week following surgery with a peak at days 2 to 3. It is important to realize that the likelihood of being in sinus rhythm 4 weeks following cardiac surgery is the same regardless of the strategy of rate or rhythm control employed. The authors choose to restore and maintain sinus rhythm in patients who are highly symptomatic in AF or difficult to rate control. Their preferred strategy is to load with amiodarone and continue therapy for a total of 6 weeks following surgery. Alternatives to amiodarone in this population include sotalol and dofetilide. Type 1A drugs are also useful particularly for patients with renal insufficiency.

Prophylactic therapy for AF prevention before cardiac surgery: It is well established that the discontinuation of previously prescribed β-blockers is associated with an increased risk of postoperative AF. It is therefore important to maintain β-blocker therapy through cardiovascular surgery. Amiodarone can be initiated in the week or weeks before electively scheduled cardiac surgery. This strategy will reduce the occurrence postoperative AF.

Atrial Fibrillation Post MAZE or Percutaneous Atrial Fibrillation Ablation Procedure

AF frequently occurs in the immediate period post MAZE or percutaneous AF ablation procedure. AF should be differentiated from atrial tachycardia, which also can occur as an arrhythmic complication of these procedures. In both circumstances, these arrhythmias often subside over a period of weeks. As a result, many practitioners choose to treat their postprocedure patients with an antiarrhythmic drug (AAD) for 4 to 12 weeks after the procedure.

Ischemia/Infarction as a Trigger for Atrial Fibrillation

AF is rarely, if ever, a manifestation of acute ischemia or infarction. When it does, it is usually in the setting of CHF with or without mitral regurgitation (MR) and is associated with a poor prognosis. It is common to develop AF with CHF or MR which develops in the setting of infarction. It is not common to develop AF in an uncomplicated MI or as a sole manifestation of ischemia or infarction. The authors do not recommend routine evaluation for coronary

artery disease in patients with new onset AF unless there is other clinical evidence of ischemia.

artery disease in patients with new onset AF unless there is other clinical evidence of ischemia.

Familial Atrial Fibrillation

There are likely multiple forms of familial AF. One phenotype which is easily identified is families with multiple members who develop AF at a young age (younger than 40 years). These patients often have significant atrial electrical dysfunction with sinus node dysfunction.

Alcohol and Atrial Fibrillation

Binge drinking is commonly associated with AF. Moderate alcohol consumption is probably not a risk for AF; however, excessive alcohol use does seem to predispose to AF.

Specific Electrocardiographic Patterns of Atrial Fibrillation

The term coarse as is often used when atrial activity in lead V1 appears to be organized and is relatively high amplitude. If the remainder of the leads have low-amplitude fibrillatory waves and the ventricular response is irregularly irregular this rhythm should be characterized as typical AF.

A regular ventricular response during AF, particularly if slow, is indicative of heart block. This is shown in Figure 6-2.

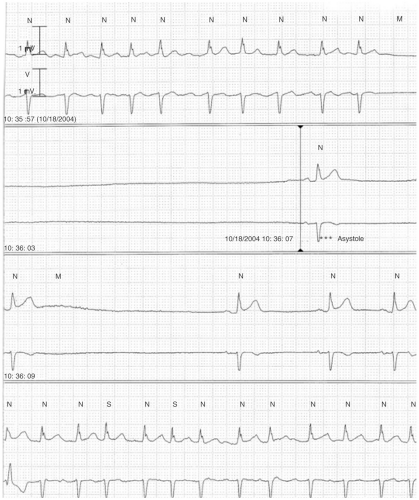

Tachybrady Syndrome

Tachybrady syndrome refers to the presence of rapid and slow rhythms in the same patient (see Fig. 6-3). Most commonly this is AF with a rapid ventricular response and sinus bradycardia. This bradycardia often manifests as a prolonged sinus pause at the time of conversion from AF or flutter to sinus rhythm (Fig. 6-3).

Symptoms and Hemodynamic Consequences Associated with Atrial Fibrillation

Most patients with new-onset AF have symptoms at the onset of their disease. With time and therapy many patients will report a significant reduction in their symptoms even with persistence of AF. The most commonly reported symptoms include dyspnea, palpitations, fatigue, and chest pain. Frequent urination may also be described as a consequence of atrial stretch-induced release of atrial natriuretic peptide. Patients with diastolic dysfunction, particularly those with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and aortic stenosis, develop symptoms and hemodynamic compromise due to the loss of the atrial contribution to ventricular filling. Most other patients do not suffer significantly from the loss of atrial filling. Symptoms associated with AF result predominantly from a rapid ventricular response. This is particularly true if tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy develops. Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy is characterized as a global cardiomyopathy which develops as a consequence of a rapid ventricular response. It is also believed that the ventricular irregularity associated with AF can be hemodynamically disadvantageous. Syncope or lightheadedness can also be associated with AF. This is almost always due to a sinus pause at the termination of AF, particularly in those with sinus node dysfunction. AF should be considered a proarrhythmic arrhythmia, particularly in the setting of old MI and CHF. AF can induce ventricular arrhythmias in this patient population.

Workup of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree