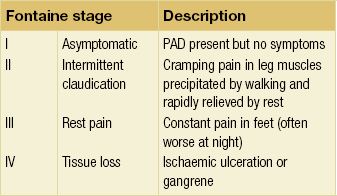

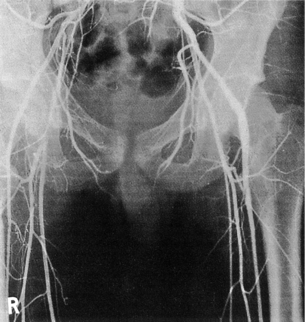

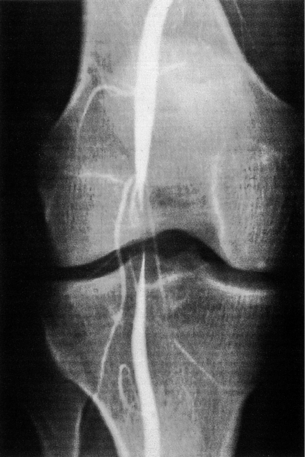

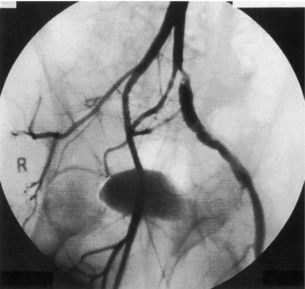

2 The differential diagnosis includes osteoarthritis of the hip or knee and lumbar nerve route irritation. Patients with spinal stenosis may have symptoms of IC that are very similar to intermittent claudication due to vascular disease.1 Whereas patients with vascular claudication get pain relief by just standing still, patients with spinal stenosis need to relieve the pressure in the spinal canal, which they do by sitting or lying down. A history of pain on standing as well as walking therefore suggests neurogenic claudication due to spinal stenosis. Patients with osteoarthritis of the hip with referred pain down the leg and a history similar to claudication usually experience some pain in the buttock or groin when turning their body, even in a sitting or supine position.The pain is not relieved by standing still as the patient needs to lessen the burden on the joint. In addition, pain from osteoarthritis typically begins when walking and gets better after some exercise. Although the diagnosis can usually be established by history and examination alone, minimally invasive investigations, including an exercise test to exclude arterial disease, may be reassuring. Arterial occlusions can be well tolerated when collaterals can develop, which may provide the same volume flow at rest as in normal individuals.3 Examples include the thigh muscles around the superficial femoral artery at the adductor canal, which is well collateralised by the profundafemoris artery and occlusions of the iliac arteries, where collaterals through the pelvis and buttock may result in normal resting pressures and even a palpable foot pulse (Fig. 2.1). Significant PAD is usually associated with an ABPI of <0.9 (see later), but in such cases an exercise challenge will result in a fall in ankle pressures and disappearance of the distal pulses. If such patients have only limited physical activity they may be asymptomatic. However, this definition has been criticised because the pressures required for healing in the presence of ulceration or gangrene may be higher and ankle pressures are often falsely elevated in patients with diabetes (see later).5 The Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus (TASC) II suggests that an ankle pressure of <70 mmHg or a toe pressure of <50 mmHg is more realistic in the presence of ulceration or gangrene. CLI in its very mild form may start with pain in the forefoot at night sufficient to disturb the patient’s sleep when the patient is in supine position, thereby cancelling the effect of gravity on blood flow to the lower limbs.7 When the patient hangs the leg out of the bed or if they stand up and walk, thereby increasing the blood flow to the foot, the pain is relieved. If the patient constantly hangs their feet out of bed at night, or even sleeps sitting in a chair, the limb swells due to dependency oedema. This can lead to a vicious circle with more tissue damage and the key is to use strong painkillers (usually opiates) so that the limb can be kept in the supine position overnight to relieve the oedema prior to arterial reconstruction. To the experienced eye the diagnosis of CLI seems obvious, but it is easy to miss a small ischaemic lesion on the heel or between the toes. When established necrosis or gangrene is present with absent limb pulses there is no doubt about the diagnosis. The stage when critical ischaemia without necrosis or gangrene is present (Rutherford II 4) is characterised by pallor when the leg is elevated above the heart and by redness when hanging down (Buerger’s or Ratshow’s test positive). The dark red colour is caused by the dilated capillaries of the foot (Fig. 2.2). Normally, only one-third are open at any time but in the state of critical ischaemia autoregulation is paralysed and, as a consequence, all capillaries are open.8 It may take a while for pallor on elevation to occur but capillary refill will be abolished immediately. In this congenital anomaly, the embryonic axial limb artery, the sciatic artery, does not obliterate and remains continuous with the popliteal artery, providing the major blood supply to the lower limb. The anomaly is bilateral in 22% of cases and is commonly associated with failure of the iliofemoral vessels to develop properly. The presenting symptoms include pain and a pulsatile mass in the buttock due to aneurysmal degeneration of the artery as it emerges from the sciatic foramen. Thrombosis or distal embolism may lead to acute ischaemia.9 Although pedal pulses may be present, the femoral pulse will be reduced or absent if the iliofemoral vessels are hypoplastic (Cowie’s sign) and IC will result if neither system has developed properly (Fig. 2.3). Symptomatic patients can be treated by combined bypass grafting and endovascular exclusion of the aneurysm.9 Asymptomatic patients should be monitored for aneurysm development. CAD, caused by a cystic abnormality of the adventitia of the artery, most commonly affects the popliteal artery and may present with IC. The contents resemble that of a ganglion and the cysts may be connected to the synovium of the knee joint. IC may be severe and of rapid onset. The condition should be particularly suspected in young patients without significant risk factors for PAD. Pedal pulses sometimes disappear on knee flexion. Arteriography may show an unusually smooth ‘hourglass’ or eccentric stenosis (Fig. 2.4). Ultrasound scanning will demonstrate the cystic abnormality, as will computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance (MR) scanning. Angioplasty is ineffective. The affected segment of artery requires resection and repair with an interposition vein graft via a posterior approach.10 The condition is not common but should be suspected when a young patient, particularly an athlete, complains of classic critical ischaemia. It can be anatomical or functional; in the anatomical variant, the artery courses around the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle rather than between the two heads or, more rarely, passes deep to the popliteus muscle. Compression of the artery occurs during flexion, resulting in IC. Aneurysmal degeneration and/or thrombosis may develop. Two-thirds of cases are bilateral and the popliteal vein is involved in 10%.11 Examination may reveal reduction or obliteration of pedal pulses during active plantar flexion. Duplex scanning or arteriography using this manoeuvre may also demonstrate kinking or compression of the popliteal artery. CT or MR scanning can also demonstrate the anatomical abnormality. Symptomatic patients should be treated by the division of the medial head of gastrocnemius and/or reconstruction of the popliteal artery. Surgery may be indicated for an asymptomatic contralateral limb whenever anatomical entrapment is detected.12 In the functional variant of the condition, an anatomically normally positioned artery is compressed against a hypertrophied gastrocnemius or the soleal muscle ring. Unlike the anatomical variant, functional entrapment should only be treated when symptomatic. Although FMD usually affects the renal and carotid arteries, it can affect the proximal upper and lower limb arteries in young people, causing IC. The external iliac artery appears the commonest site of involvement and arteriography may demonstrate a classic beaded appearance (Fig. 2.5). Patients with iliac FMD should be screened for renal involvement. Symptomatic stenoses usually respond well to angioplasty.13 Buerger’s disease (thromboangiitis obliterans) is a systemic vasculitis that affects medium-sized arteries and veins. It should be considered in any heavy smoking young male claudicant, especially if they are of Middle or Far Eastern origin.14 Vasospastic symptoms and superficial thrombophlebitis commonly occur and patients may progress rapidly to, or present with, CLI. The pathophysiology and management of this condition and other causes of vasculitis such as Takayasu’s are covered in Chapter 12. In addition to previous myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary artery bypass grafting and arterial surgery, direct enquiry should include symptoms suggestive of angina or transient cerebral ischaemia. Although approximately 30% of patients with symptoms of limb ischaemia will have a history of myocardial infarction, it is not uncommon that angina or transient ischaemic attacks are diagnosed for the first time. The investigation and treatment of these symptoms usually have a higher priority than PAD (see Chapter 3). The enquiry for cardiovascular risk factors is equally important and obviously covers smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and a detailed drug and family history. Upper extremity exertional pain, postprandial abdominal pain and erectile dysfunction in men are other important potential clues to the presence of significant occlusive atherosclerotic disease in other vascular territories. Signs of atherosclerosis and its risk factors in any part of the cardiovascular system should be elicited as well as examination findings to establish the site and severity of PAD. Examination should be systematic and include the following: measurement of blood pressure in both arms and the inter-arm difference; palpation of all peripheral and central pulses; pulse rate, rhythm and heart sounds; examination of the hands and abdominal aorta; careful inspection of the feet, particularly of skin integrity, colour and temperature. In addition, skin changes and calf hair loss may also be suggestive of chronic lower limb ischaemia.16 The body mass index (BMI) should be calculated by measuring height and weight.17 This is a good estimate of obesity, a predictor of life expectancy and anaesthetic risk, but also adds to the patient’s walking incapacity. In some cases, weight loss will reduce the patient’s symptoms substantially. Palpation of pulses is subjective, and is influenced by the sensitivity of the fingers, the experience of the examiner, the obesity of the patient and the warmth of the room. Any patient with symptoms from the lower limb that could be of ischaemic origin should have ABPI assessed. The femoral artery should always be palpable, whether it is pulsatile or occluded, if it is examined properly, unless the patient is very obese (Fig. 2.6). If it is occluded it can often be palpated as a hard cord due to atherosclerosis. If the pulse feels weak it is often because of proximal obstruction causing reduced femoral artery blood pressure. The popliteal pulse is more difficult to palpate, particularly in a well-muscled or obese subject, but should always be felt to exclude an aneurysm (Fig. 2.7). Palpation of the foot pulses should always be described. It may be difficult when the foot is swollen or the room is cold. Presence or absence of foot pulses on physical examination is a ‘weak’ and subjective sign of PAD and should always be supplemented by objective measurements (ABPI). The absence of a single foot pulse may have little clinical significance and, although it should be recorded, it is not an indication for more detailed investigation. Figure 2.6 Palpation of the femoral pulse may require both hands except in the thin patient. One hand pushes the lower abdomen out of the way and the other palpates the femoral artery/pulse. Patients present occasionally with a classic history of IC, but with palpable foot pulses. These patients may have been investigated previously for joint disease or lumbar nerve root irritation even though their history may be ‘typical’ of claudication. Most often, there is proximal aorto-iliac disease with collaterals through the pelvis, sufficient to produce adequate or even normal pulses at rest. In patients who complain of symptoms only on exercise, it is rewarding to examine the leg following an exercise challenge. This can be done quite simply in the consulting room or by asking the patient to walk up and down the corridor (or on a treadmill if available). Even elderly patients find it easy to exercise the calf muscle by a repeated ‘tiptoe’ while leaning on the couch (Fig. 2.8). The patient returns to the couch so that the pulses can be examined immediately after exercising for 1 minute. More important, the post-exercise ABPI is measured. The perfusion pressure at the ankle can be measured using a tourniquet and insonating the pedal arteries with Doppler ultrasound. The patient should be rested for more than 5 minutes, lying supine, and a standard blood pressure tourniquet applied just above the ankle, with the tourniquet being 50% wider than the limb diameter. The tourniquet cuff is inflated above the systolic pressure, when the pedal Doppler signal should disappear. On gradually lowering the cuff pressure, the Doppler signal reappears at the ankle systolic pressure (Fig. 2.9). The probe should be held at a 30–60° angle to the vessel in order to achieve the optimal signal. The systolic blood pressure is then taken from the brachial artery in the same way and the ABPI calculated as the ratio of the ankle to the brachial systolic pressures. Blood pressures should be assessed on both arms at the patient’s first visit since 3–5% of PAD patients may have supra-aortic obstructive disease as well. The higher of the two brachial blood pressures should be used as the reference for calculating ABPI. The toe pressure can be measured using the strain-gauge technique, photo-plethysmography or laser Doppler to detect the disappearance and reappearance of the pulse as the cuff is inflated and deflated.19 A warm room is essential to avoid vasospasm and most often the feet need a 15- to 20-minute warm-up period. Expressed as a ratio to brachial artery pressure, toe pressures are normally lower than ABPI at 0.8–0.9. As a refinement to Buerger’s test, the level at which a pedal Doppler signal disappears on elevation of the foot may be taken as a crude measure of ankle arterial pressure when the calf arteries are incompressible.21 This technique has been called the ‘pole test’ as the foot is raised alongside a calibrated pole marked in mmHg (0.73 mmHg = 1 cmH2O). This technique is only useful in severe ischaemia as it is not possible to raise the foot high enough to measure normal pressures. All patients should be investigated for risk factors for atherosclerosis as modification reduces both the risk of fatal cardiovascular events and the need for arterial reconstruction. The risk factors associated with PAD are essentially the same as those for ischaemic heart disease, and include smoking, lack of exercise, unhealthy dietary habits (too much fat from meat, dairy fat, too little fish and vegetables), dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus and hypertension (see Chapter 1). All patients with PAD require a full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), urea and electrolytes, plus random blood glucose, and lipids. Anaemia can present with symptoms of leg ischaemia, as can polycythaemia. An elevated ESR (or viscosity) may indicate raised fibrinogen, which seems an important factor in the development of PAD and vascular thrombosis. Renal impairment is often associated with PAD and requires detection before contemplating both imaging and intervention. Arterial thromboembolism is relatively infrequent in patients under the age of 50. Young patients with PAD should have a thrombophilia screen as antiphospholipid antibodies or antithrombin III deficiency may lead to repeated rethrombosis following either angioplasty or reconstruction. Hyperhomocysteinaemia can cause accelerated atherosclerosis and should be excluded in young patients with PAD. Acute peripheral ischaemia in a younger patient with no history of PAD should warrant cardiac work-up, including at least electrocardiogram (ECG) and echocardiography. The investigation of cardiovascular risk factors is summarised in Box 2.1. As 25% of patients who claim to have stopped smoking may be lying, measuring a smoking marker may be required, although the effect of such ‘proof’ on smoking cessation is questionable.22

Assessment of chronic lower limb ischaemia

Intermittent claudication (IC)

Critical ischaemia

Rare causes of ischaemia

Persistent sciatic artery

Cystic adventitial disease (CAD)

Popliteal artery entrapment

Fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD)

Buerger’s disease

History and examination

Examination

Exercise challenge

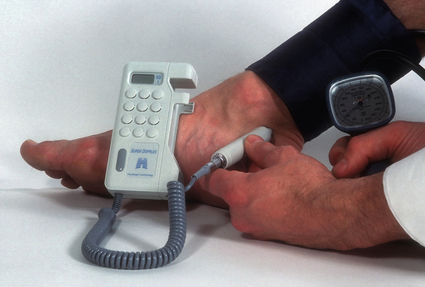

ABPI measurement using a hand-held Doppler device

Toe pressures

The ischaemic angle

Risk factors

Assessment of chronic lower limb ischaemia