Chapter 50 Arrhythmias in Women

Gender-Related Differences in Electrocardiography and Cardiac Electrophysiology

Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability

In 1920, Bazett showed that women have higher resting heart rates than do men.1 This observation was confirmed in 1989 by the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, in which the average heart rate in women was 3 to 5 beats/min faster than in men. This gender-related difference in heart rate is present as early as childhood, but the etiology of this disparity is unclear. Potential explanations include differences in exercise tolerance, autonomic modulation, and the intrinsic properties of the sinus node. It has been shown that this difference persists even after sympathetic and parasympathetic blockade with propranolol and atropine, which suggests an intrinsic difference in the sinus node itself as the etiology. Women have also been found to have shorter sinus node recovery times after overdrive pacing.

Gender-related differences are also present in heart rate variability. Several studies of patients who underwent 24-hour Holter monitoring showed that women have a smaller low-frequency component and a smaller low-frequency to high-frequency ratio over the range of heart rate variability, which suggests a greater parasympathetic influence in female hearts.2 This finding is probably related to hormonal influences on cardiac autonomic modulation. Postmenopausal women who are not on estrogen replacement therapy have lower baroreflex sensitivity and smaller low-frequency and high-frequency spectral components of heart rate variability compared with age-matched men or with women on estrogen replacement therapy. It is possible that these differences are related to the worse outcomes experienced by women after myocardial infarction (MI), since reduced baroreflex sensitivity and a reduced low-frequency component of heart rate variability are associated with an increased risk of life-threatening arrhythmias after MI.

Q-T Interval and QT Dispersion

Bazett also noted that women have longer Q-T intervals than do men on the surface electrocardiogram (ECG).1 However, in a normal population, boys and girls have similar corrected Q-T intervals.3 At the time of puberty, the average male QTc interval shortens, leaving adult women with longer QTc intervals compared with adult men. As men age, their QTc intervals gradually increase, and by age 65 years, their QTc intervals are again comparable with those in women.

QT dispersion—the difference between the longest and the shortest Q-T intervals on a 12-lead ECG—is greater in men than in women. Increased dispersion of repolarization correlates with re-entrant–type ventricular arrhythmias, which may explain, in part, the increased risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in men compared with women. In contrast, absolute Q-T interval prolongation may result in arrhythmias related to early afterdepolarizations (EADs), specifically polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (torsades de pointes), the risk of which is higher in women. The principal gender-related differences in electrocardiography and cardiac electrophysiology are summarized in Table 50-1.

Table 50-1 Principal Gender-Related Differences in Electrocardiography and Cardiac Electrophysiology

| ELECTROPHYSIOLOGICAL PARAMETER | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Heart rate | Higher in women |

| Heart rate variability | Decreased in postmenopausal women |

| Sinus node recovery time | Shorter in women |

| AV conduction properties | |

| P-R, A-H, H-V intervals | Shorter in women |

| AV block cycle length | Shorter in women |

| Incidence of dual AVN pathways | Similar in both genders |

| Slow pathway effective refractory period | Shorter in women |

| QRS complex | Shorter duration and lower amplitude in women |

| Nonspecific repolarization changes | More frequent in women |

| QTc interval | Longer in post-pubertal women |

| QT dispersion | Lower in women |

AV, Atrioventricular; AH, atrial-His; HV, His-ventricular; AVN, AV nodal.

Specific Arrhythmias

Atrial Fibrillation

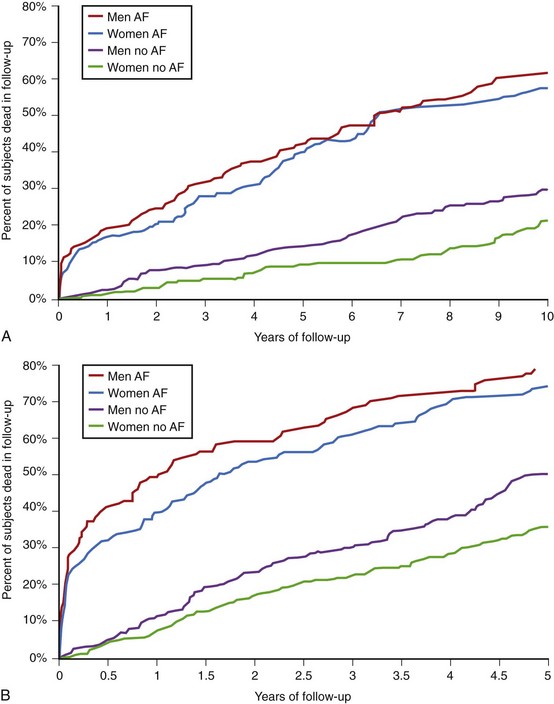

In women, valvular heart disease and heart failure are the predominant cardiac diseases associated with AF, while men more commonly have AF in association with ischemic heart disease.2 Women with paroxysmal AF tend to present with longer episodes and faster ventricular rates. They are also more likely to have cardioembolic complications. Most importantly, AF has been shown to diminish the survival advantage in women, increasing the risk of death regardless of gender (odds ratio [OR], 1.5 for males, 1.9 for females) (Figure 50-1).4

Although the findings above suggested that a more aggressive treatment approach for women with AF may be warranted, the best way to accomplish this is not readily apparent. Management of thromboembolic risk is difficult in older patients because of the competing risks of stroke and bleeding from anticoagulation.5 Maintenance of sinus rhythm, an attractive option at first glance, may not be beneficial, as indicated by the results of the AFFIRM trial, in which no difference was shown in survival or quality of life with a rhythm control strategy versus a rate control strategy.6 In addition, women’s greater risk of Q-T interval prolongation and torsades de pointes, as well as the more frequent occurrence of bradyarrhythmias associated with amiodarone use for AF requiring pacemaker insertion, must be recognized when choosing to prescribe antiarrhythmic drugs.

Congenital Long QT Syndrome

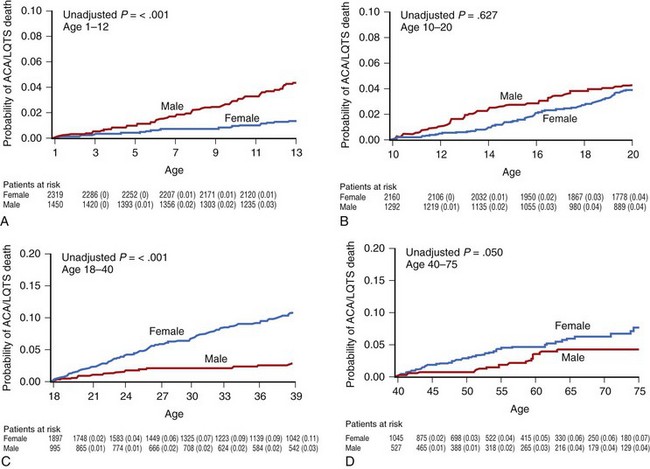

Several studies from the International LQTS Registry have shown that this gender-related difference is age dependent (Figure 50-2, A to D). Locati et al found that before puberty, boys were at higher risk for cardiac events (syncope, cardiac arrest, or SCD). Another study from the same registry found that during childhood, boys who were LQT1 carriers had a significantly higher risk of cardiac events compared with girls, whereas no gender-related difference existed among those patients who were LQT2 or LQT3 carriers. In a more recent analysis from the registry, in which the endpoint of aborted cardiac arrest or SCD was assessed in 3015 children with LQTS, boys were found to have a threefold increase in the risk of these lethal arrhythmias during childhood. Hobbs et al studied 2772 registry patients who were followed up between the ages of 10 and 20 years and found that boys age 10 to 12 years had a fourfold higher risk of SCD compared with girls, but found no significant gender-related difference in the age range of 12 to 20 years (see Figure 50-2, B).

Sometime between the end of puberty and the beginning of adulthood, a reversal of gender-related risk occurs. Adult women in the age range of 18 to 40 years have been found to have a 2.7-fold higher risk of aborted cardiac arrest and SCD compared with men (Figure 50-2, C). The cumulative probability of aborted cardiac arrest or SCD in this age group is higher among women (11%) than among men (3%).7 Even after the age of 40 years, when patients with LQTS are expected to have a lower rate of arrhythmias and when the increased prevalence of acquired cardiac diseases should overshadow the effects of LQTS, patients with this entity still experience a high risk for life-threatening cardiac events. This was recently shown by Goldenberg et al, who studied 2759 subjects from the registry and found that the hazard ratio (HR) for affected (QTc >470 ms) individuals versus unaffected (QTc <440 ms) individuals for aborted cardiac arrest or SCD among patients between the ages of 40 and 60 years was 2.65. In this age group, women are affected by a marginally but significantly higher rate of aborted cardiac arrest and SCD compared with men (Figure 50-2, D).7 The difference in the timing of events is likely related to the shortening of Q-T intervals in boys after puberty, as discussed earlier. In patients carrying the common LQT1 genotype with mutations that impair the slowly activating delayed rectifier potassium (K+) current (IKs), 79% of lethal ventricular tachyarrhythmias are associated with exercise and faster heart rates. Since boys tend to perform more intense physical activities compared with girls, they could be exposed to a greater risk of arrhythmic events during childhood. After puberty, testosterone shortens the QTc interval in boys, whereas estrogens may modify the expression of K+ channels and have a dose-dependent blocking effect on IKs. These hormonal influences provide relative protection to postpubertal boys and to men, whereas they predispose female patients to lethal arrhythmias, particularly during menses and pregnancy.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree