Chapter 25 Appropriate Use of Nuclear Cardiology

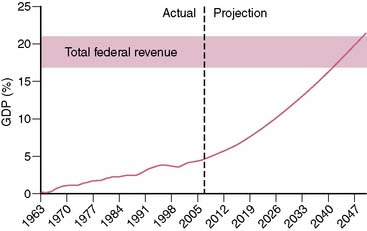

Spending on health care in the United States has been increasing at an alarming rate. Over the past 40 years, the annual increase in federal health care spending has outpaced the annual growth of the gross domestic product (GDP) by an average of 2.5%.1 Currently, U.S. health care spending exceeds $2 trillion and accounts for 16% of the GDP.2 The Congressional Budget Office projects that if current trends were to persist over the next 40 years, federal spending on Medicare and Medicaid (ignoring state spending on Medicaid) would approach 20% of the GDP (Fig. 25-1). To appreciate the significance of this projection, it is important to realize that total federal revenue over the past 60 years has ranged between 17.0% and 20.9% of the GDP and has never in the history of the United States exceeded 20.9%.3 In other words, the projected federal spending on Medicare and Medicaid alone by the midpoint of this century would equal (as a percentage of the GDP) what has historically been spent on all components of the federal budget (social security, defense, education, interest on the national debt, agriculture, etc.).

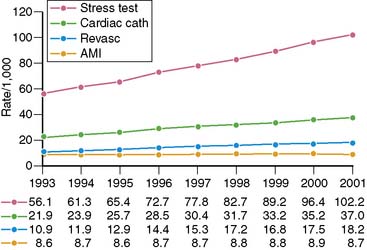

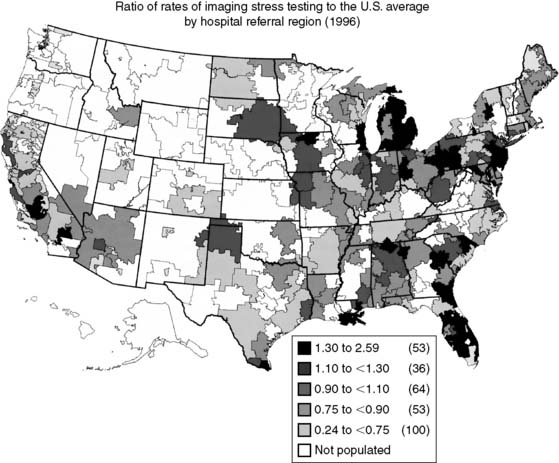

Spending on cardiovascular diseases accounts for a substantial proportion of total health care spending. In 2007, the estimated direct and indirect costs for cardiovascular diseases were nearly $432 billion.4 The rate of growth in cardiac imaging services has recently been especially steep. Stress imaging, which as defined by Medicare incorporates both stress single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and stress echocardiography, grew at a rate of 6% per year between 1993 and 2001.5 This rate of growth for stress imaging far exceeded the rate of growth in acute myocardial infarction, cardiac catheterizations, or coronary artery revascularization procedures during this time period (Fig. 25-2). Published data further demonstrate that the use of stress imaging is highly heterogenous across the country, with rates of imaging varying by more than 10-fold between different geographic regions (Fig. 25-3).6

In response to these concerns about the use of cardiovascular imaging, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF) initiated a process to address the appropriateness of different cardiovascular imaging procedures.7 Examining the appropriateness of medical resource use is not a novel concept.8–10 The American College of Radiology (ACR) published appropriateness criteria for radiologic imaging procedures in 1995.11 The ACR criteria address a variety of imaging procedures across multiple medical and surgical disciplines. They have not been widely applied to the practice of clinical cardiology. The ACCF appropriateness criteria focus on single cardiovascular imaging procedures. In October 2005 the ACCF, in collaboration with the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology (ASNC), published the first set of appropriateness criteria, which addressed SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging (SPECT MPI).12 Since then, appropriateness criteria have been published for cardiac computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging,13 transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography,14 stress echocardiography,15 and coronary revascularization.16

The approach the ACCF has followed to examine the appropriateness of a cardiovascular imaging modality is based on a method originally developed by the RAND Corporation, in collaboration with researchers from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), to examine the appropriateness of medical and surgical procedures.17 Although the ACCF methodology is based on the RAND/UCLA approach, it is important to note that the RAND/UCLA method focuses on the therapeutic benefit of invasive procedures, whereas cardiovascular imaging has different goals. Another major difference relates to the number of clinical scenarios considered. The RAND/UCLA document addresses literally hundreds of clinical scenarios. The ACCF approach limits the number of situations to fewer, more broadly defined clinical scenarios where imaging is most commonly applied. The ACCF method follows the precedent set by the ACR and uses the modified Delphi method to develop appropriateness criteria. With this approach, members of an expert panel assign ratings for imaging to various clinical indications, initially without any interaction with other panel members. The panel then meets to discuss the assigned ratings, and members again assign ratings after this panel interaction. The ACCF approach differs from the ACR approach by not trying to achieve consensus of panel members and by using fewer rounds of ratings.7

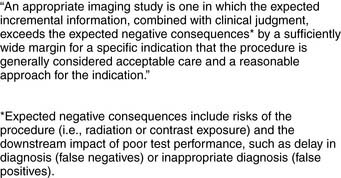

The definition of an appropriate imaging study selected by the ACCF is:7

It is important to note that the “negative consequences” listed in this formal definition do not directly mention cost of the procedure. However, the ACCF methodology document does acknowledge the importance of cost: “Therefore, to identify the true risks of imaging, both inherent risks and downstream effects, including costs, must be considered. As such, if the imaging study provides little incremental information for an indication over standard clinical judgment and care, then cost considerations should contribute to deeming the procedure inappropriate.”7

For each imaging modality being rated for appropriateness, the ACCF method follows 4 steps:

It is important to distinguish between appropriateness criteria and clinical guidelines. ACCF/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines are based on comprehensive reviews of the medical literature (evidence-based) and employ a level-of-evidence rating scheme to assign indications to diagnostic procedures and therapies. Conversely, the appropriateness criteria are based on consideration of benefit versus risk of performing the imaging modality. Panel members are encouraged to consider the published literature when assigning a rating for a given indication, but there is no requirement that the rating be based on the literature. The emphasis is on a less formal approach of whether it is “reasonable” to consider performing the imaging study.7

The technical panel for SPECT MPI appropriateness criteria was composed of 12 physicians, 58% of whom were specialists in nuclear cardiology. This panel rated 52 clinical indications for SPECT imaging. Most (49) of these indications addressed stress SPECT for detection or risk assessment of coronary artery disease, one indication addressed assessment of viability, and two indications addressed evaluation of ventricular function (Tables 25-1 through 25-9).12 Of the 52 indications, 27 were rated appropriate, 12 uncertain, and 13 inappropriate.

Table 25-1 Detection of Coronary Artery Disease: Symptomatic

| Indication | Appropriateness Criteria (Median Score) | |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluation of Chest Pain Syndrome | ||

| 1. | I (2.0) | |

| 2. | U* (6.5) | |

| 3. | A (7.0) | |

| 4. | A (9.0) | |

| 5. | A (8.0) | |

| 6. | A (9.0) | |

| Acute Chest Pain (in Reference to Rest Perfusion Imaging) | ||

| 7. | A (9.0) | |

| 8. | I (1.0) | |

| New-Onset/Diagnosed Heart Failure With Chest Pain Syndrome | ||

| 9. | A (8.0) | |

A, appropriate; I, inappropriate; U, uncertain.

* Median scores of 3.5 and 6.5 were rounded to the middle (U).

Table 25-2 Detection of Coronary Artery Disease: Asymptomatic (Without Chest Pain Syndrome)

| Indication | Appropriateness Criteria (Median Score) | |

|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic | ||

| 10. | I (1.0) | |

| 11. | U (5.5) | |

| New-Onset or Diagnosed Heart Failure or LV Systolic Dysfunction Without Chest Pain Syndrome | ||

| 12. | A (7.5) | |

| Valvular Heart Disease Without Chest Pain Syndrome | ||

| 13. | U (5.5) | |

| New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation | ||

| 14. | U*(3.5) | |

| 15. | A (8.0) | |

| Ventricular Tachycardia | ||

| 16. | A (9.0) | |

A, appropriate; I, inappropriate; U, uncertain.

* Median scores of 3.5 and 6.5 are rounded to the middle (U).

Table 25-3 Risk Assessment: General and Specific Patient Populations

| Indication | Appropriateness Criteria (Median Score) | |

|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic | ||

| 17. | I (1.0) | |

| 18. | U (4.0) | |

| 19. | A (8.0) | |

| 20. | A (7.5) | |

A, appropriate; I, inappropriate; U, uncertain.

Table 25-4 Risk Assessment with Prior Test Results

| Indication | Appropriateness Criteria (Median Score) | |

|---|---|---|