Approach to the Chest Radiograph

Especially for neophyte interpreters of radiographs, it is essential to approach the images in the proper way. For $29.95 we will send you the ancient secret approach to the chest radiograph discovered by Leonardo da Vinci. It not only improves your interpretation of chest radiographs, it helps you to win friends and influence people.

In reality, only the first sentence of the last paragraph is true. Any approach to the chest radiograph is likely to be successful if it results in a reproducible systematic scheme for evaluating radiographs. We detail one such approach that may help you to keep things organized. You are welcome to use this or to adapt it or to create your own system.

The key thing to avoid, especially as you begin to look at radiographs, is the “gestalt” approach. By gestalt we mean looking at the radiograph and hoping to receive an overall impression in a mysterious way (perhaps via radiowaves, ESP, or ESPN). We confess that as we have become more experienced at interpreting chest radiographs, we do make an initial rapid scan of a study and often come up with a quick gestalt of normal or abnormal. Even so, we supplement this initial impression with a more systematic review of the image for a more complete diagnosis. This initial gestalt is not always correct, but with experience it has been reassuring how often relatively small or subtle abnormalities on a radiograph will, in essence, announce their presence, calling attention to themselves even at the first cursory review of the image. This is presumably what experience does for a radiologist. Many years of experience do not decrease the necessity for a formal review scheme that reduces errors of carelessness. Still, it is probably nice to realize that image interpretation will not always be a purely mechanical exercise, that there will be an element of art as the image itself “talks to you.” We now present a recommended approach.

Approach to the Radiograph

The approach is based on the observation that many inexperienced film readers think of a chest radiograph as a lung radiograph. This leads to interesting errors of perception, such as missing major abnormalities completely when the lungs are normal and missing key extrapulmonary abnormalities that completely elucidate the diagnosis when the lungs are abnormal.

For that reason, we recommend saving the lungs for last. One way to make this easier to accomplish is to start on the periphery of the radiograph and work one’s way in. Thus, we recommend beginning the assessment of the chest radiograph by examining the bones and soft tissues of the chest wall and also by assessing the neck and the upper abdomen. Next come the pleural spaces bilaterally. We then skip across the lungs to examine the mediastinum, followed by the heart and great vessels. With all that out of the way, the lungs are finally assessed. A more detailed examination of this approach follows.

A Brief Consideration of Position and Projection

Before we get into the detailed approach to the radiograph, a brief discourse on position and projection is advisable. Because radiographs are generally two-dimensional representations of three-dimensional anatomy, we recommend two right-angle projections of a structure for best depiction of that structure. In the chest, this means that we try to obtain a frontal chest radiograph, either posteroanterior (PA) (x-ray beam enters the patient from behind and emerges through the front, where the x-ray cassette or digital plate awaits) or anteroposterior (AP) (beam from in front traverses the anterior thorax and emerges through the back) and a lateral radiograph. We prefer a PA radiograph when the patient’s condition permits, in part to limit the portion of the radiograph obscured by the soft tissues of the heart; anterior structures like the heart are more magnified on an AP view than on a PA view. We similarly prefer a left lateral radiograph (beam enters via the patient’s right side and emerges from the left side), which also limits the magnification of the heart. A standard chest radiograph is obtained with a distance of 72 inches from the x-ray source to the cassette or digital plate and with the patient in the upright position, taking and holding a deep inspiration.

This idealized version of reality is not always reproducible in real life. Some patients are unable to follow instructions (language barrier, decreased mentation) or unable to take a deep breath (dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain). Acutely ill patients may be unable to stand; semiupright radiographs can sometimes be obtained with the patient in bed, but supine radiographs are another potential outcome. Patients who cannot come to our department for radiographs can be examined with portable equipment but almost always in the AP projection and seldom with a lateral view. The distance from x-ray source to image may have to be less than 72 inches, resulting in magnification of the entire chest. These technical modifications have consequences with regard to visualization and diagnosis of thoracic abnormalities.

Outside the Thorax: Soft Tissues

Careful assessment of the extrathoracic soft tissues occasionally plays a critical role in the evaluation of the chest. One of the most important things to which we try to pay attention is symmetry of the soft tissues of the neck and the breasts (Fig. 3.1). This is because asymmetry may indicate prior surgery, and this may in turn indicate prior cancer.

Assess symmetry of breasts.

Assess symmetry of neck soft tissues.

Assess for soft tissue calcifications, gas, or metal.

You might believe that interest in prior cancer is based on generating a differential diagnosis for abnormalities that are subsequently detected. You would be only partly right. The differentiation of normal from abnormal is, in our opinion, the single most important job of the chest radiologist and also the single hardest job of the chest radiologist. Although malpractice attorneys paint a picture of missed abnormalities as “obvious,” such abnormalities do not come prospectively labeled (except in textbooks such as this). In many instances a question arises as to whether a finding is an overlap of normal structures, a normal variant, a benign abnormality, or a more important finding.

Pretest probability is an important factor in deciding whether a finding is real or artifact and important or unimportant. Experience teaches that pre-employment chest radiographs on patients in their twenties are virtually certainly normal. Chest radiographs on “twenty-somethings” with chest pain are almost as frequently normal. In such a setting, a questionable nodule is virtually never a real nodule, and we almost never bring up the

need for follow-up radiographs or oblique radiographs or limited thin-section computed tomography or positron emission tomography.

need for follow-up radiographs or oblique radiographs or limited thin-section computed tomography or positron emission tomography.

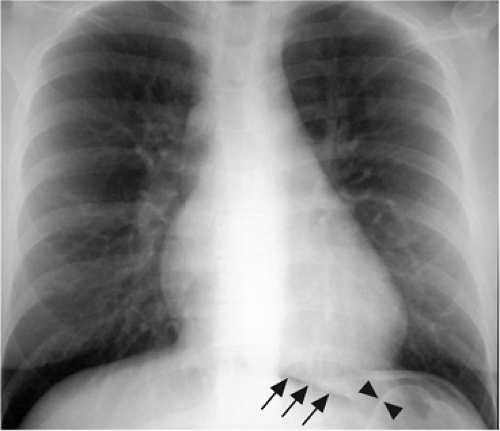

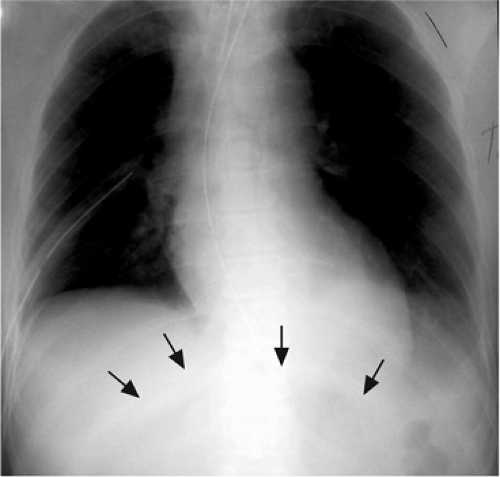

Figure 3.1 Prior right mastectomy. Left breast outline is visible (arrows), and there is also asymmetric lucency over the right lung base laterally. |

But what if the patient has been treated for cancer? Although cancer is not commonly found in such young patients, we do occasionally see breast cancer in that age group, which could result in mastectomy. We do occasionally see thyroid cancer in that age group, which could result in neck dissection. So the observation of asymmetric neck or breast soft tissues could change the pretest probability significantly and could make us read the radiograph and interpret the questionable abnormalities very differently.

Of course, the patient is certainly aware that he or she has had previous breast or thyroid cancer. Unfortunately, for studies like chest radiographs we as interpreting radiologists almost never see the patients. The referring physician is also certainly aware of this diagnosis. You may be tempted to believe it is ridiculous that a radiologist’s knowledge of such diagnoses would have to rely on his or her ability to make observations on the radiograph. All we can say is, “Just wait until you start looking at radiographic requisitions.” The best we can often hope for is clinical history that is not out-and-out incorrect or frankly misleading. Many requisitions are completed by overworked clerks who know very little medicine. If they are told to order chest radiographs, they write a history like “rule out infiltrate.” Even an accurate history that details symptoms and current clinical concerns may not include relevant past information thought not to be of current clinical concern (such as remote breast cancer).

The bottom line is that observations such as previous mastectomy are important, clinically relevant, influential in deciding whether a study is normal or abnormal, and critical to differential diagnosis of abnormalities. It is likely that many health systems will go to a computerized order entry system in the not-so-distant future. One day, it may be easy to retrieve all relevant clinical information for every ordered radiograph. Until that day, the systematic approach to the radiograph requires an assessment of the symmetry of neck and breast soft tissues.

Outside the Thorax: Abdomen

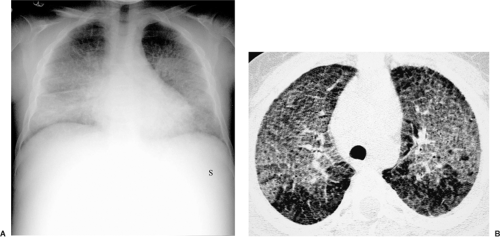

A complete consideration of abdominal diseases is outside the scope of this text. Nevertheless, some observations are relevant. Because of the centering of an upright chest radiograph and its technique, it is often far better than an upright abdominal radiograph at

depicting free intraperitoneal gas (Fig. 3.2), usually under the right hemidiaphragm. Although larger amounts of gas are required, supine chest radiographs can also be evaluated for intraperitoneal gas (Fig. 3.3).

depicting free intraperitoneal gas (Fig. 3.2), usually under the right hemidiaphragm. Although larger amounts of gas are required, supine chest radiographs can also be evaluated for intraperitoneal gas (Fig. 3.3).

Assess lucent structures: bowel gas pattern, free intraperitoneal gas, bowel wall gas, and other extraintestinal gas (retroperitoneal, biliary, etc.).

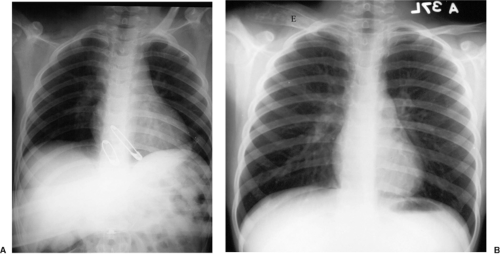

Splenomegaly can be an important finding for explaining intrathoracic abnormalities. It may raise the possibility of leukemia or lymphoma, helping to explain mediastinal and hilar lymph node enlargement or thoracic opportunistic infection. In a trauma patient it may indicate splenic hematoma or laceration, tying in with left pleural effusion or pneumothorax. It may go along with hepatomegaly and/or ascites in a patient with liver disease, elucidating right pleural effusion. Splenomegaly is generally diagnosed via medial displacement of gas in the stomach and caudal displacement of gas in the splenic flexure along with mass-like soft tissue in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen (Fig. 3.4).

Assess soft tissue structures: organomegaly and soft tissue masses.

Figure 3.3 Supine free intraperitoneal gas. There is a large central lucency in the upper abdomen (arrows). |

Although most bowel gas will be outside the field of view of a chest radiograph, inspection of the bowel contained in a chest radiograph may yield evidence of bowel obstruction, infarction, or other abnormalities. At a minimum, this can lead the alert chest radiologist to recommend standard abdominal radiographs for better evaluation. Similarly, patients with lower thoracic or shoulder pain may actually be experiencing referred pain from upper abdominal disease. Such abnormalities may result in mass effect on upper abdominal bowel.

Outside the Thorax: Bones

As with abdominal findings, skeletal findings could constitute a separate textbook entirely. Nevertheless, a few observations are in order. One is that it is very difficult to detect skeletal abnormality without careful examination of individual bones; look at the trees, forget the forest. Especially when there is chest pain, try to compare the ribs from side to side, one by one. Trauma is another setting where painstaking inspection of visualized bones can prevent important mistakes.

It is interesting to note that the absence of a structure usually seen may be much harder to detect than the presence of abnormality of that structure (Fig. 3.5). Similarly, inexperienced interpreters may have difficulty distinguishing between variants of normal and abnormalities. Side-to-side comparison is particularly helpful in these settings; unlike abnormalities, normal variants are often bilateral and are reasonably symmetric.

Assess opaque structures: skeletal abnormalities, calculi, and metallic foreign bodies.

Compare for symmetry of bilateral structures.

If there are two views, assess both (sternum and spine better seen on lateral view).

With abnormalities at the periphery of the chest, it may be difficult to distinguish between those originating in the pleura and those arising in the chest wall (extrapleural). Shape of the lesion may be helpful (Chapter 17), but adjacent skeletal abnormality is absolute proof that the lesion is in the extrapleural space.

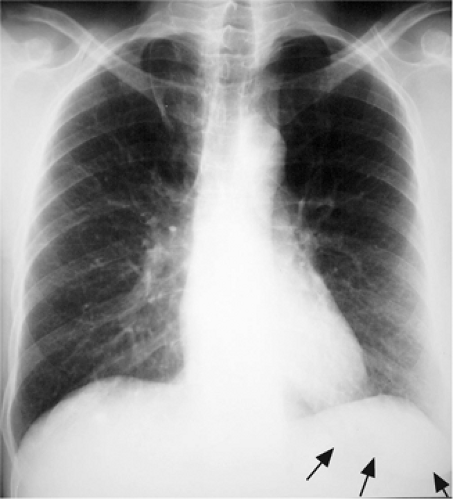

Pleura

The pleural spaces are potential spaces at the periphery of the lungs. For the purposes of this chapter the key pleural abnormalities we want to detect are pneumothorax and pleural effusion. Both illustrate the importance of patient position on the radiographic appearance of abnormality. Air and fluid in the pleura migrate in opposite directions; fluid moves to the dependent aspect of the space, whereas air moves to the nondependent aspect. With a patient upright, we look for pneumothorax at the thoracic apex and for pleural effusion in the caudal hemithorax (Fig. 3.6). However, many patients being examined for these findings are hospitalized critically ill patients. They may be unable to assume the upright position, in which case fluid will spread out along the posterior aspect of the chest (Fig. 3.7) and air will rise to the anterior aspect of the chest. Leading to more confusion, such patients may be quickly propped upright for a radiograph without allowing air or fluid the few minutes it may take to redistribute as expected.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree