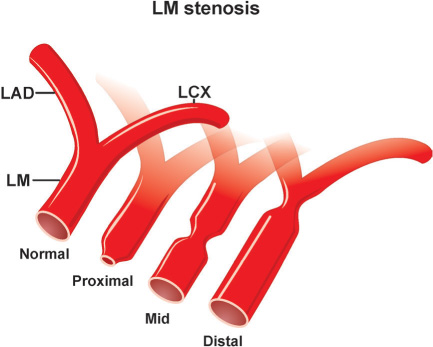

A diligent precatheterization work-up can help an operator to suspect the presence of left main disease, and reduce the risk of catastrophic complications of left coronary cannulation (Figure 18.1).1,2

Steps to be performed in the cardiac catheterization laboratory when precatheterization work-up suggests presence of LM coronary stenosis are as follows:

- •Step 1: Crash cart is easily accessible, defibrillation pads are placed on the patient’s chest, a temporary pacemaker and IABP equipment are ready to be placed if needed. An interventional cardiologist should be notified in advance about the potentially high-risk diagnostic cardiac catheterization procedure. The operator should not plan to perform cardiac catheterization on high-risk patients at the end of the day. Nonionic contrast should be used.

- •Step 2: When a JL coronary catheter is used to cannulate the LCA, extra caution should be exercised to avoid an unintended engagement of the LCA ostium by the catheter tip when the guidewire is removed. The operator should advance the catheter tip over the guidewire deep into the cusp or stop in the mid-ascending aorta superior to the LCA ostium. This maneuver secures careful approach to the LM coronary artery from below or above under continuous pressure monitoring. Nonselective cusp injection of contrast in shallow RAO projection with minimal caudal angulation or shallow LAO projection with minimal cranial angulation is highly recommended to visualize the ostium of the LM prior to catheter engagement.

- •Step 3: When the catheter tip has engaged the coronary ostium, pressure waves are checked to make sure that no damping or ventricularization of the pressure waveform has occurred, as ECG tracings and the patient’s clinical condition are closely monitored. If pressure damps and/or ventricularizes upon engagement of the LM, ostial stenosis is very likely. The operator should withdraw the catheter slightly, recheck the pressure waveform, then inject about 2 mL contrast gently while taking cine images. If the problem is ostial LM stenosis, an attempt can be made to gently reposition the catheter tip to eliminate pressure damping. Performing nonselective angiography or using a “hit and run” technique, where 4–6 mL of contrast dye is injected in RAO caudal and LAO cranial views with biplane angiography, are highly recommended. Alternatively, rapid rotational angiography from shallow RAO caudal or shallow LAO cranial projections to RAO cranial view can be performed with simultaneous catheter withdrawal into the ascending aorta. Aortic pressure is compared with the pressure obtained from the LM ostium and the gradient recorded. These views and information are usually sufficient to provide the cardiothoracic surgeon with a roadmap for CABG surgery. Additional injections should be avoided since frequent LM cannulations can lead to vasospasm or plaque rupture/dissection with catastrophic consequences.

- •Step 4: If the patient’s condition remains stable, the operator proceeds with right coronary angiography. For the patient with significant LM stenosis with occluded and/or a small and nondominant right coronary artery, admission to the ICU is recommended. Any patient with clinical symptoms of ischemia or even with minor signs of hemodynamic instability requires immediate IABP placement and urgent cardiothoracic surgery and interventional cardiology consultations.

- •Step 3: When the catheter tip has engaged the coronary ostium, pressure waves are checked to make sure that no damping or ventricularization of the pressure waveform has occurred, as ECG tracings and the patient’s clinical condition are closely monitored. If pressure damps and/or ventricularizes upon engagement of the LM, ostial stenosis is very likely. The operator should withdraw the catheter slightly, recheck the pressure waveform, then inject about 2 mL contrast gently while taking cine images. If the problem is ostial LM stenosis, an attempt can be made to gently reposition the catheter tip to eliminate pressure damping. Performing nonselective angiography or using a “hit and run” technique, where 4–6 mL of contrast dye is injected in RAO caudal and LAO cranial views with biplane angiography, are highly recommended. Alternatively, rapid rotational angiography from shallow RAO caudal or shallow LAO cranial projections to RAO cranial view can be performed with simultaneous catheter withdrawal into the ascending aorta. Aortic pressure is compared with the pressure obtained from the LM ostium and the gradient recorded. These views and information are usually sufficient to provide the cardiothoracic surgeon with a roadmap for CABG surgery. Additional injections should be avoided since frequent LM cannulations can lead to vasospasm or plaque rupture/dissection with catastrophic consequences.

Coronary Anomalies

The most frequent coronary anomaly observed during selective coronary angiography is the absence of a LM coronary artery, with the LCX and LAD either sharing a common origin from the aorta but splitting immediately, or originating separately in the left coronary cusp (LCC).2,3 When approached with a JL coronary catheter, the tip may selectively engage either the LAD or LCX. Most of the time it is difficult to opacify both arteries simultaneously, and each artery should be cannulated separately. Occasionally, it can be accomplished by rotating the JL catheter counterclockwise in order to engage the LAD, and clockwise to get the LCX. Sometimes the catheter needs to be changed according to a simple rule: If the LCX artery is engaged on the initial attempt with the JL4 catheter, the operator should use a JL3.5 catheter to get the LAD, and vice versa (e.g., if the smaller-curve JL catheter engages the LAD, a larger-curve catheter is used to engage the LCX). If the above approach does not yield adequate information, other catheters, including the AL or MP (technique described in Chapter 7), should be considered.

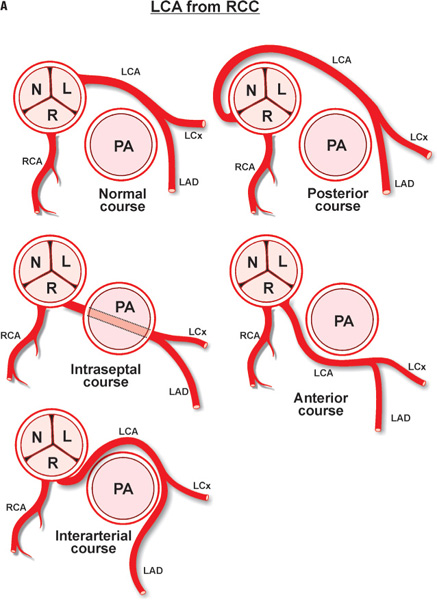

The LM coronary artery occasionally may be difficult to cannulate by a preformed JL coronary catheter, despite originating from the LCC, when the ostium is either deep down or high up in the cusp, or when it is posteriorly or anteriorly oriented. A nonselective “cusp” shot frequently helps the operator to visualize the origin of the LM and choose the appropriate catheter and approach. Usually, an anomalously originating LM coronary artery located in the left coronary sinus can be approached and successfully cannulated by the MP or AL coronary catheters (counterclockwise rotation for posterior location, and clockwise rotation for anterior position). A LM originating from the right sinus of Valsalva is rare (0.15% of patients), and even more rare when originating from the noncoronary sinus.3 Figure 18.2 depicts some of the most common coronary anomalies in adults.

WHICH ANOMALIES ARE DANGEROUS?

Occasionally, the LCX shares a common ostium with the RCA and can be opacified with a JR catheter. When the RCA originates from the left sinus of Valsalva, its course can also frequently be malignant, especially if its ostium is anteriorly located in relation to the LM ostium. To selectively cannulate this artery, the operator may consider using JL5 or JL6, AR, or AL coronary catheters.

Referral to CT angiography in case of a suspected malignant course of an anomalous left or right coronary artery is highly recommended. The RCA origin in the right sinus of Valsalva can also vary: An inferior ectopic origin can be most successfully cannulated with a MP catheter; an anterior ectopic origin in the cusp is best cannulated with AL or AR catheters; a posterior ectopic origin can be cannulated best with an MP catheter; a superior/anterior ectopic origin above the sinotubular junction is best approached with MP (see Chapter 7), AL, or 3D-RCA coronary catheters. When using a 3D-RCA catheter, the operator should slowly withdraw the catheter into the ascending aorta from the cusp with minimal clockwise rotation and frequent test injections to orient the tip of the catheter towards the coronary ostium.

Test injections of contrast are used with attempts to cannulate any anomalous coronary vessel with clockwise or counterclockwise maneuvers of the catheter. For example, if the anomalous coronary artery is located more anteriorly, step-by-step clockwise rotation with test injections will opacify the artery gradually, since the tip of the catheter will be approaching the ostium. On the other hand, step-by-step counterclockwise rotations with nonselective test injections will poorly opacify the same artery, since the tip of the catheter will be pointing away posteriorly from the ostium. Similarly, small, nonselective test injections are helpful when the operator attempts to determine if the ostium of the anomalous coronary artery is located high or low in the cusp. In order to evaluate the course of an anomalous coronary artery arising from another (anomalous) cusp, an operator should take an RAO view. If the initial course of the coronary artery is posteriorly directed, the course is more likely to be “benign”, on the other hand if the initial course of the artery is anteriorly directed the course is more likely to be “malignant”.

Coronary Spasm and Myocardial Bridge

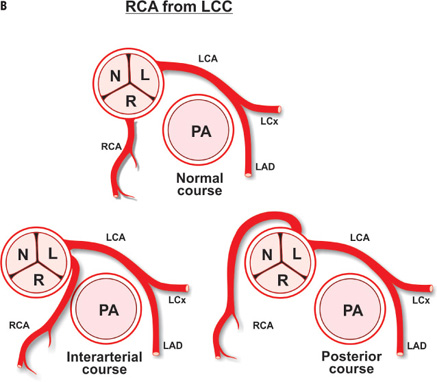

The decision to further investigate a patient with angiographically normal coronary arteries or with physiologically insignificant stenosis is made when the clinical suspicion of coronary vasospasm causing myocardial ischemia is high based on the combination of subjective (history and physical) and objective data (ECG and noninvasive cardiac imaging) (Figure 18.3A).4,5 Occasionally, the simple cannulation of the coronary artery or a simple, forced episode of hyperventilation in patients predisposed to coronary vasospasm may provoke vasospasm that can be directly visualized by selective coronary angiography and resolved by intracoronary administration of nitroglycerin. In patients with symptoms related to cold exposure, a cold pressor test (immersing hands into icy cold water) can be performed in the cardiac catheterization laboratory.

FIGURE 18.3Panel A is a diagram of coronary vasospasm; Panel B is an example of myocardial bridging.

If these maneuvers do not provoke coronary vasospasm, the operator may proceed with pharmacologic provocative testing. The 2 most frequently used agents for this purpose in the United States are methylergonovine and acetylcholine. In Europe and Japan, ergonovine maleate is used as well. To reverse the effect of these medications, intracoronary nitroglycerin is administered as needed. Bradycardia and hypotension, which may follow acetylcholine infusion, can be treated by intravenous administration of atropine 0.5 mg every 3–5 minutes up to a total dose of 2 mg. Major contraindications to performing pharmacological provocative testing are severe LV dysfunction, severe aortic stenosis, amenorrhea in premenopausal women (possible pregnancy), and significant LM coronary stenosis.

Different protocols for pharmacological provocative testing have been described in the literature. Ergonovine maleate can be given intravenously at doses of 50 mcg every 5 minutes until a total maximal dose of 350 mcg; a positive response or side effects necessitate termination of the test. Ergonovine can also be given by intracoronary injection of 5–10 mcg up to a total cumulative dose of 50 mcg. Methylergonovine can be given every 3 minutes in successive intravenous boluses of 1, 2, 3, and 4 mcg/kg. Again, a positive response or side effects necessitate termination of the test. Acetylcholine can be injected in incremental doses of 20, 50, and 80 mcg every 3 minutes into the RCA, and in incremental doses of 20, 50, and 100 mcg every 3 minutes into the LCA. A positive response or side effects necessitate termination of the test. Intracoronary administration of nitroglycerin reverses vasospasm of the coronary arteries provoked by ergonovine derivatives or acetylcholine.

Epicardial coronary arteries may occasionally take an intramyocardial course, which may lead to the entrapment of various lengths of the artery under the myocardial tissue, described as a “bridge” (Figure 18.3B).6 The mid-LAD followed by the RCA are most commonly involved. In general, myocardial bridging is a benign phenomenon, but in rare cases it can lead to compromised blood flow and myocardial ischemia. The mechanism for this complication includes systolic and more importantly diastolic compression of the vessel lumen, due to an inability or delayed ability of muscle relaxation. Furthermore, vasospasm and the development of atherosclerosis in the proximal or distal segments, just prior to, or right after the “bridge” can be contributing factors. Coronary angiography can reveal the systolic narrowing or “milking effect” of the epicardial coronary artery with or without persistent diastolic reduction in vessel lumen diameter. To assess functional significance of myocardial bridging it may be required to measure fractional flow reserve after dobutamine infusion or evaluate its anatomy by intravascular ultrasound. Detailed description of these methods is beyond the scope of this manual.6

Aortic Stenosis

When dealing with a severely calcified aortic valve, fluoroscopy of the valve in different projections can outline the orifice of the stenotic valve and may help crossing the valve with the guidewire. To cross a severely stenotic aortic valve, a soft, straight-tipped, 0.035-inch guidewire can be used. The optimal view for crossing the aortic valve is RAO; techniques for different catheters have been described in Chapter 9. An intravenous heparin bolus (40 units/kg) should be administered after the arterial access is obtained to keep the ACT ≥ 200 seconds, with frequent (2–3 minutes) removal and cleaning of the guidewire during the procedure. The operator should never apply excessive force in an attempt to push the wire or catheter across the stenotic valve; rather, a patient trial-and-error approach with slight maneuvering of the catheter and guidewire is the way to success. Steps are as follows:

- •Step 1: Place a 7- or 8-Fr sheath into a central vein and a 6- or 7-Fr long (90 cm) sheath (to minimize the effects of peripheral amplification, avoid manipulating iliac/abdominal aortic atherosclerosis, and allow evaluation of concomitant subaortic fixed and/or dynamic obstruction, if suspected) through the common femoral artery into the ascending aorta.

- •Step 2: Place a Swan-Ganz catheter into the IVC. Check O2 saturation, and advance the Swan-Ganz catheter into the SVC. Recheck O2 saturation, and pull back into the RA, advancing the catheter into the RV and the PA while recording pressure. Then check O2 saturation in the PA and aorta, advance the Swan-Ganz catheter into the PAWP position and record pressure, deflate the balloon, and withdraw the catheter back into the PA.

- •Step 3: If a left-to-right shunt is suspected, do the full shunt run; otherwise, deflate the balloon, remove the Swan-Ganz catheter, and flush both sheaths.

- •Step 4: Place a 4- to 5-Fr end-hole long (125 cm) MP catheter through the arterial sheath over the regular guidewire into the ascending aorta beyond the tip of the sheath, record arterial pressures from the tip of the MP catheter and from the femoral sheath simultaneously, and note the difference.

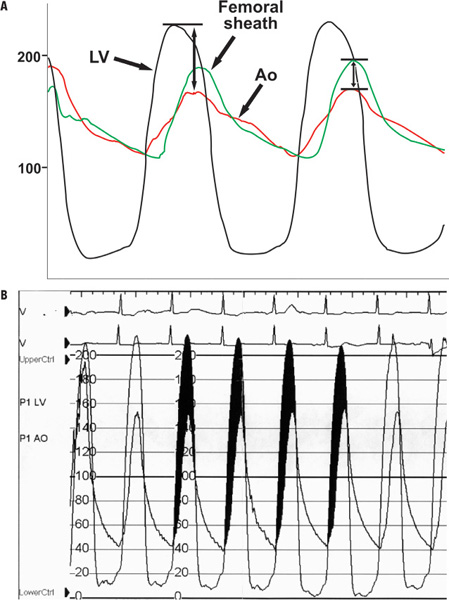

- •Step 5: Use a soft-tipped, straight, long wire to cross a stenotic valve; if needed, use AL1 or AL2 catheters, and if so, use exchange J-tip guidewire to eventually exchange AL catheter to an end-hole MP. Record LV pressure followed by simultaneous pressure recording from the LV cavity and femoral sheath (50 and 100 mm/second paper speed and 0–200 mm Hg scale; 0–400 mm Hg scale can be used if needed) (Figure 18.4).

- Simultaneous left ventricle and aortic pressure tracings on a “200 scale” show a mean gradient of 59 mm Hg according to the computer using the selected “shaded areas.” Note that the upstroke of the LV and the aortic tracings are nearly simultaneous. This type of measurement can be obtained by doing a pull-back tracing and then superimposing the aortic and the left ventricular tracings, with the limitations of the beats not being simultaneous. When doing this, the onset of the upstrokes of each complex should be matched.

Note the difference and add it to the delta pressure of the ascending aorta and the femoral sheath difference in order to calculate the peak-to-peak gradient, quantify the mean gradient. When done, record the peak-to-peak pressure gradient on pull-back (Figure 18.5).

Left ventricle to aortic pullback tracing demonstrating a gradient of 210 mm Hg – 110 mm Hg = 100 mm Hg peak to peak. Note the anacrotic notches on the aortic tracings (black arrow) and the delayed upstroke.

If the aortic pressure increases > 5 mm Hg following the withdrawal of the catheter from the LV into the ascending aorta (Carabello sign),7,8 the operator should suspect the presence of extremely severe aortic stenosis (AVA < 0.7 cm2). If the operator is dealing with the clinical question of differentiation between true severe aortic stenosis versus pseudostenosis in the presence of a low transvalvular mean gradient, pharmacological (dobutamine or nitroprusside; see Box) amplification of cardiac output is used. An increase in the mean aortic gradient to ≥ 40 mm Hg, and an absence of significant increase of calculated aortic valve area in the presence of increased stroke volume ≥ 20%, suggest true aortic valve stenosis. The gradient should be measured and averaged from 5 to 10 cardiac cycles in patients with normal sinus rhythm and atrial fibrillation respectively. If noninvasive studies have suggested concomitant subaortic fixed and/or dynamic obstruction, record simultaneous pressure tracings from the apical LV cavity and femoral sheath. Note the difference, and add to the delta pressure (femoral sheath pressure minus ascending aortic pressure) to calculate the total peak-to-peak gradient. Ask the patient to breathe out and perform the Valsalva maneuver, and record simultaneous pressures from the LV cavity and femoral sheath. When done, provoke PVCs by gently contacting the endocardium with the catheter tip, while continuing to record simultaneous pressures. If a dynamic obstruction is present, the Valsalva maneuver will lead to an increase of the existing baseline gradient; in the post-PVC beat, an increase of the pressure gradient will accompany a drop in aortic pulse pressure (Brockenbrough-Braunwald-Morrow sign) (Figure 18.6).9

Subsequently, record the pressure on a slow pull-back of the catheter and repeat above-described maneuvers in order to locate the site of dynamic obstruction in the LV. In case of a fixed subaortic stenosis in the LVOT, attempt to “selectively” measure the LVOT and AS gradients by moving the long sheath over the end-hole catheter into the LV and positioning it before the LVOT obstruction while the tip of the end-hole catheter is located in the LV beyond the obstruction. The “selective” measurement of the AS gradient can be performed by withdrawing the sheath into the aorta while the end-hole catheter tip is positioned between the aortic valve and the LVOT obstruction.

- •Step 6: Remove the catheter and flush both sheaths.

- •Mild AS: mean gradient < 25 mm Hg

- •Moderate AS: mean gradient 25–39 mm Hg

- •Severe AS: ≥ 40 mm Hg

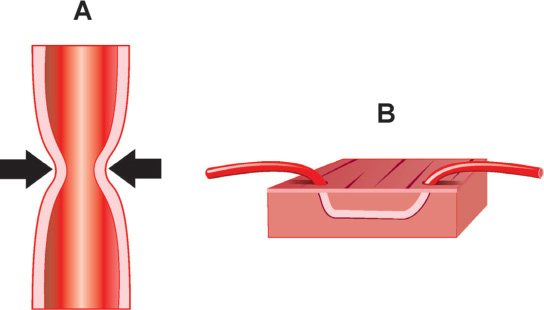

FIGURE 18.4Simultaneous LV and aortic pressure tracings in aortic stenosis are shown. Panel A: Diagram; Panel B: Patient tracing.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree