Anomalies of the Sinuses of Valsalva and Aortico-Left Ventricular Tunnel

Luca A. Vricella

Duke E. Cameron

INTRODUCTION

Anomalies of the aortic root typically present as either enlargement or anomalous communication between supravalvular aorta and left ventricular (LV) cavity. In the former (sinus of Valsalva [SoV] aneurysm), the process develops progressively and is often associated with connective tissue disorders that manifest diminished tensile strength of the aortic wall. The latter (aortoventricular tunnel) is usually a perturbation in cardiac development that is nearly always clinically evident in the newborn period or in early infancy.

Aortic root dilation is also a late finding in children who have undergone repair of various forms of congenital heart defects, such as common arterial trunk, transposition of the great arteries, or bicommissural aortic valve. With regard to SoV aneurysm, we will focus on isolated dilation of a single sinus since diffuse aortic root enlargement (seen more commonly in association with other forms of congenital, atherosclerotic, or connective tissue disease) is detailed elsewhere in this book.

ANEURYSM OF THE SINUS OF VALSALVA

Morphologic Considerations

Each coronary sinus is limited inferiorly by the curvilinear hinge point of the corresponding aortic valve cusp. The intercommissural triangles are inferior to the festoon-like line of ventriculoaortic continuity (commonly referred to as “annulus”), whereas the sinotubular junction delineates the circular superior margin of the aortic root.

The sinuses of Valsalva are normally thinner than the tubular portion of the aorta, and this macroscopic finding is usually associated with a lesser degree of histologic representation of the tunica media. In patients with SoV aneurysm, this normal characteristic is accentuated. Thinning of the aortic wall with disconnection of the media from the aortoventricular junction is seen histologically and increases over time.

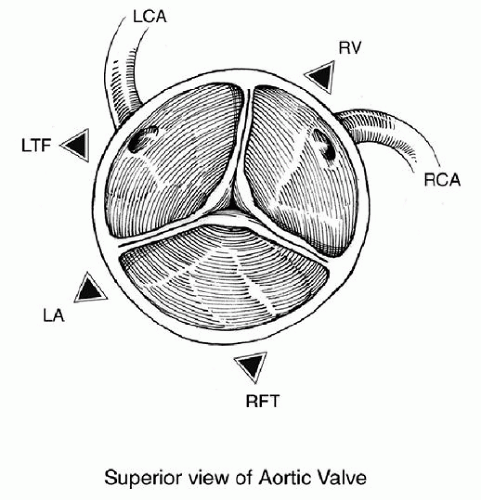

Figure 85.1 schematically demonstrates the anatomic relations of the aortic root with the adjacent cardiac structures as seen from the operating surgeon’s viewpoint. These relations account in turn for the different modes of clinical presentation that are seen with pathologic enlargement of the SoVs. Dilation of the right SoV (most common) will, therefore, typically progress in the direction of the right ventricular outflow tract, whereas the noncoronary sinus will involve either left or right atrial chambers. Isolated enlargement of the left SoV (with possible rupture into the left atrium) is the rarest form of this pathology. Although typically SoV aneurysms involve one of the three sinuses as a well-defined diverticular outpouching, two or three sinuses can be affected simultaneously by the pathologic process. A ventricular septal defect (VSD) is observed in 25% to 50% of cases.

Aneurysms of the SoVs are rare. They are observed in 0.1% of autopsy series and in 0.14% to 0.96% of large operative cohorts; they are also five times more common in patients of Asian descent.

Clinical Presentation

Pathologic SoV enlargement is often diagnosed incidentally in asymptomatic patients. Clinical presentation can occur as an aortic catastrophe (free intrapericardial rupture), acutely with endocarditis or intracardiac rupture (within right or left atrium, right ventricle), or with a more indolent clinical course during childhood. In this last mode of presentation, progressive dilation, distortion, and subsequent loss of cusp coaptation can lead to clinically significant aortic valvar insufficiency.

Rupture or fistulization almost always involves the right coronary sinus, while a minority of patients have involvement of the noncoronary (up to 30%) or left coronary (<2%) sinuses. Perhaps, in the largest reported surgical series (149 patients with SoV aneurysm), intracardiac rupture was seen at presentation in just <50% of cases. Aortic root rupture into a neighboring cardiac chamber is furthermore a rare event in the first two decades of life. If we extrapolate from data available in young patients with connective tissue disorders, this is not surprising. In a meta-analysis of 286 patients age <20 years with Marfan syndrome, Knirsh and coworkers reported aortic dissection in only five patients (1.7%) and rupture in three patients (1.0%). All but one patient (14 years old) were 19 years of age at the time of the acute event involving the aortic root. When intracardiac rupture of a SoV aneurysm occurs, a mean survival period of 3.9 years has been reported in untreated patients.

When symptomatic, patients may present with chest discomfort, palpitations, dyspnea on exertion, or florid congestive heart failure, with diastolic hypotension and pulmonary overcirculation from acute left-to-right shunting between aorta and right-sided chambers. Of patients with fistulization, >60% will be symptomatic at presentation. A precordial continuous murmur is usually heard. The clinical picture can be that of sepsis in the setting of endocarditis (up to 20% of patients). Dyspnea or even cyanosis can result from progressive right ventricular outflow tract obstruction by an enlarging SoV aneurysm that protrudes into the right ventricle. Atrioventricular conduction abnormalities are present in 10% of patients.

The diagnosis is easily confirmed by transthoracic echocardiography, with cardiac catheterization reserved for patients with significant risk factors for coronary artery disease.

Surgical Indications and Technique

Indications for surgery in patients with uniform dilation of the aortic root are

fairly well established. Enlargement beyond 5.0 cm, or enlargement >1.0 cm per year, is a well-accepted indication for surgical intervention in asymptomatic patients. Aortic regurgitation from distraction of the commissures or asymmetric sinus enlargement with ventricular dilation is also an accepted indication for surgery, as is aortic dissection. Threshold for intervention can be lowered for young adults with lesser degrees of enlargement when there is a family history of aortic dissection or rupture. In our practice, we have applied the same adult criteria for intervention to child, as the risk of aortic rupture in the first decade is quite low. An exception is the Loeys-Dietz syndrome, where rupture and dissection can occur in much smaller aortas and at a much earlier age.

fairly well established. Enlargement beyond 5.0 cm, or enlargement >1.0 cm per year, is a well-accepted indication for surgical intervention in asymptomatic patients. Aortic regurgitation from distraction of the commissures or asymmetric sinus enlargement with ventricular dilation is also an accepted indication for surgery, as is aortic dissection. Threshold for intervention can be lowered for young adults with lesser degrees of enlargement when there is a family history of aortic dissection or rupture. In our practice, we have applied the same adult criteria for intervention to child, as the risk of aortic rupture in the first decade is quite low. An exception is the Loeys-Dietz syndrome, where rupture and dissection can occur in much smaller aortas and at a much earlier age.

In the case of isolated enlargement of a single sinus, indications are not as well defined. Strong consideration to surgical intervention should be given in asymptomatic patients because of the high likelihood of progressive increase in size and the possibility of rupture or endocarditis. The latter is obviously an indication for urgent surgical correction.

A transesophageal echocardiogram is routinely performed after induction of anesthesia to confirm preoperative diagnosis, assess valvular competence, and rule out the possibility of a concomitant septal defect.

The operative approach is via median sternotomy, with bicaval venous cannulation and cardiopulmonary bypass and moderate hypothermia (24 to 28°C). A right superior pulmonary vein vent is inserted, and the heart is arrested with either antegrade or retrograde administration of cold blood cardioplegia solution; direct intracoronary delivery is used in case of ruptured aneurysm or significant aortic regurgitation, or with retrograde coronary perfusion. If the tip of the “windsock” is palpable through the right atrium, it can be compressed manually to prevent runoff of antegrade administered cardioplegia. We use continuous topical cooling as well as carbon dioxide flooding of the surgical field to minimize retention of air within the left-sided chambers.

A transverse aortotomy is carried out and the root anatomy is assessed. An oblique right atriotomy is performed next, allowing for the identification of both ends of the aneurysm or of the fistulous tract in case of rupture (Fig. 85.2). In case of protrusion or rupture into the right ventricle, exposure can be obtained through a right atriotomy or a limited ventriculotomy (Fig. 85.3). When the fistulous tract or diverticulum is in the right ventricular infundibulum, the lesion can also be exposed through a transverse pulmonary arteriotomy. The defect must be repaired through the aortic root, using a patch of autologous or bovine pericardium to exclude the aortic inlet into the aneurysm. Primary closure predisposes to a higher risk of recurrence (as high as 20%) or aortic valve regurgitation from deformation of the root. In case of fistulization, the opening on the atrial or ventricular side should be addressed as well. The ventricular or atrial aspect of the fistula can be closed primarily, but a patch should be used to incorporate closure of a coexisting VSD (Fig. 85.3). Great care should be taken in avoiding the atrioventricular conduction system at the time of VSD closure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree