An Integrated Approach to Risk Factor Modification

Robert C. Block

Thomas A. Pearson

Need for a Systematic Approach to Preventive Cardiology

An extensive base of scientific evidence supporting the practice of preventive cardiology grows significantly each year. The role of various risk factors in the atherosclerotic process and the effects of their reduction on clinical course have been clearly outlined in studies of vascular biology, natural history, and clinical trials. The development of consensus statements regarding clinical recommendations is helping to transform the practice of cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention, but the translation of knowledge into effective clinical practice has been shown to be consistently inadequate (1,2,3,4). The time has come to “use what we know” (3). Said another way, by Claude Lenfant, former director of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, “the real challenge of this new millennium may indeed be to strike an appropriate balance between the pursuit of exciting new knowledge and the full application of strategies known to be extremely effective, but considered underused” (5).

Rationale for a Comprehensive Prevention Strategy

The practice of cardiology has become increasingly specialized, with the creation of clinical subdisciplines limited to invasive cardiology, heart failure, hypertension, lipidology, and so on. The central thesis of this chapter emphasizes one characteristic shared by all patients with CVD, namely the need for both short-term and long-term reductions in risk of myocardial infarction and cardiac death. The rationale for a comprehensive approach to CVD risk management is therefore shared by a wide spectrum of patients (Table 14.1).

First, atherosclerosis is a diffuse disease involving multiple arterial beds and target organs, potentially leading to a host of life-threatening complications other than coronary artery disease. Once acute manifestations of ischemia are controlled, the focus of attention must be on the pathophysiology of the atherosclerotic process. Although revascularization is highly effective in relieving symptoms caused by severe atherosclerotic lesions in the short term, it cannot address the underlying diffuse nature of the atherosclerotic process. Many interventions such as the use of antiplatelet drugs, angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and β blockers, show sustained benefits compared to placebo over the long term. Clinical trials of lifestyle change and drugs that lower low-density-lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, such as hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors, show progressive gains in benefit over the course of the trials, suggesting enhanced survival benefit after several years of therapy, across a range of cardiac outcomes, such as angina, the need for revascularization, congestive heart failure, cardiac mortality, and total mortality.

Second, because atherosclerosis is a diffuse disease, it involves the renal, peripheral, and cerebrovascular beds. To focus on disease in one vascular bed without attention to inevitable multiorgan complications would detract from a cohesive preventive strategy. For many chronic vascular diseases such as peripheral arterial disease, aortic aneurysm, and cerebrovascular disease, the main cause of death is myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death. Indeed, the control of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, smoking, and other CVD risk factors demonstrates reduction in clinical events in all vascular beds, and trials frequently use a composite endpoint to provide a more comprehensive view of the intervention’s benefits.

Third, a number of randomized trials have better defined the role of risk factor management in the overall treatment of the patient with an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). One observation is that reductions in clinical events in ACS can occur rapidly after initiation of aggressive risk factor management. For example, the PROVE-IT Study (6), a randomized trial of atorvastatin 80 mg/day versus pravastatin 40 mg/day in ACS patients, gave evidence for a benefit for atorvastatin after only a few weeks of therapy, and significant benefits in the

atorvastatin arm were observed in both the 0- to 6-month and 6- to18-month periods of the study. PROVE-IT and other studies support recommendations that risk factor interventions be implemented immediately rather than put off to a follow-up visit or cardiac rehabilitation program (7).

atorvastatin arm were observed in both the 0- to 6-month and 6- to18-month periods of the study. PROVE-IT and other studies support recommendations that risk factor interventions be implemented immediately rather than put off to a follow-up visit or cardiac rehabilitation program (7).

TABLE 14.1 Rationale for Comprehensive Risk Factor Modification Integrated into the Overall Management of the Patient with Coronary Artery Disease | |

|---|---|

|

Fourth, there is strong evidence that risk factor management complements cardiologic interventions targeting ischemia, arrhythmias, and congestive heart failure. Analyses of randomized trials of antiplatelet and lipid-lowering drugs routinely identify benefits independent of β blockers, ACE inhibitors, revascularization, and so on. Indeed, certain interventions may synergize to multiply the benefits. An analysis of placebo-controlled trials of pravastatin suggests such a synergistic interaction with aspirin, in which combined aspirin and pravastatin provides greater risk reduction than that expected for the sum of risk reductions of either intervention alone (8). One consequence of these additive benefits is the striking reduction in case-fatality rates in patients in contemporary randomized trials. For example, the TNT Study suggested that, even in the atorvastatin 10-mg/day arm, the coronary death rate among patients with stable coronary disease was as low at 2.5% over the 4.9-year course of the study as compared to the threefold- to fourfold-greater coronary mortality rates in historic cohorts of patients with chronic coronary disease (9).

Fifth, the long-term medical management of CVD with drugs and devices will likely expand significantly. An increasing array of prescription medications is being added to our armamentarium, with potential for benefit as well as adverse drug–drug and drug–device interactions. Strong evidence supports the notion that statin treatment benefits everyone at high risk of CVD, regardless of their LDL, shifting the paradigm from LDL-goal attainment to one focused on universal and aggressive lipid reduction. Results of the Heart Protection Study, PROVE-IT (6), TNT (9), IDEAL (10), and others support revision of the recommendations of the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) of the National Cholesterol Education Program toward more aggressive lipid reduction, particularly for those at very high risk (7). Therefore, more patients treated with aggressive interventions require diligent monitoring for adverse side effects of single agents as well as drug interactions. The ASCOT Study may provide a good example (11). One arm of the study compared two antihypertensive regimens: β blocker (atenolol) with thiazide diuretic, as needed, versus calcium channel blocker (amlodipine) plus ACE inhibitor (perindopril), as needed. The calcium channel blocker/ACE arm led to a small (1.9 to 2.7 mm Hg) blood pressure reduction but an impressive reduction (16%) in total cardiovascular events. The β blocker/thiazide arm demonstrated an 11% reduction in high-density-lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and a 23% increase in serum triglyceride levels. HDL-cholesterol change was the largest contributor to the endpoint differences. This suggests that blood pressure management that has a detrimental effect on the lipid profile may be inferior to one that does not. If reduction in the overall risk of a cardiac event is the goal of therapy, these unforeseen effects of risk factor interventions need to be considered in selecting the “best” regimen.

Finally, a number of psychosocial benefits to the patient accrue from an integrated approach to risk factor modification. The amelioration of the effects of depression, enhanced social support, and improved compliance/adherence with lifestyle and pharmacologic interventions are all positive consequences of a comprehensive risk factor management program. An acute coronary syndrome or a revascularization procedure provides the “teachable moment” in which the patient might adopt fundamental changes in lifestyle and commitment to long-term drug therapy. The delay in instituting preventive interventions for weeks or months sends the message that these interventions are of secondary importance and mere adjuncts to more effective cardiologic procedures. As previously discussed, the evidence from randomized trials overwhelmingly supports at least as powerful a role for lifestyle and pharmacologic interventions over the short and long term as any others in modern cardiology. The message to the patient should be that the acute management of symptomatic disease must be followed up by treatment of the underlying disease process over the remainder of the patient’s life.

Evidence for the Underutilization of Interventions to Reduce Risk

The American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and other organizations have developed a number of preventive cardiology guideline statementsbased on basic science, epidemiologic, and randomized, controlled trial evidence. Despite this body of evidence and a consensus on effectiveness, use of risk reduction interventions is disappointing when seen from a variety of viewpoints.

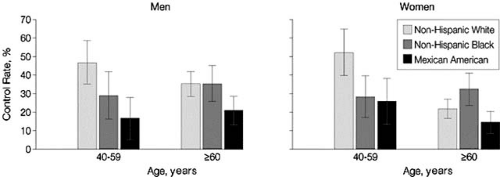

From a population perspective, blood pressure control improved in the 1990s, yet only an estimated 49% of individuals aged 65 and older with hypertension have a blood pressure of less than 140/90 mm Hg (12). Data for all age groups from the 1999–2000 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey demonstrated that 68.9% of individuals with hypertension were aware of their diagnosis, 58.4% were treated, and only 31% had their blood pressure controlled (13). Mexican Americans, women, and those aged 60 years and older had significantly lower rates of control than men, non-Hispanic whites, and younger individuals (Fig. 14.1).

The evidence also demonstrates low success in achieving lipid-lowering treatment goals, particularly in coronary heart disease and high-risk noncoronary disease groups (2). In the Lipid Treatment Assessment Project study performed in 1997 in 618 physicians who were frequent prescribers of lipid-lowering drugs, only 18% of their patients with known coronary heart disease achieved the National Cholesterol Education Program’s goal for LDL cholesterol, along with 37% of high-risk and 68% of low-risk patients. The reasons for the low success rate were

identified as a lack of the use of medications, inappropriate choices or doses of medication, and infrequent use of medicine combinations. Eighty percent of patients did not receive dietary advice. The NEPTUNE II Study (14), performed in 2004, used a protocol similar to that of the L-TAP Study. A significant improvement in achievement of LDL-cholesterol goals was found, but only 57% of CHD patients attained their LDL-cholesterol goals. Physicians in the United States also do not appear to follow national recommendations pertaining to the screening of family members of their high-risk CVD patients. In one study, the documentation of a discharge plan recommending the screening of family members of patients younger than age 55 years was made in less than 1% of inpatient medical records (15). More optimistic data reveal that hospital compliance with smoking cessation guidelines for patients with an acute myocardial infarction has improved, with an estimated 84% receiving counseling (16). The data reveal that what is achievable in clinical trials does not generally translate into everyday practice, a phenomenon otherwise known as the “treatment gap.”

identified as a lack of the use of medications, inappropriate choices or doses of medication, and infrequent use of medicine combinations. Eighty percent of patients did not receive dietary advice. The NEPTUNE II Study (14), performed in 2004, used a protocol similar to that of the L-TAP Study. A significant improvement in achievement of LDL-cholesterol goals was found, but only 57% of CHD patients attained their LDL-cholesterol goals. Physicians in the United States also do not appear to follow national recommendations pertaining to the screening of family members of their high-risk CVD patients. In one study, the documentation of a discharge plan recommending the screening of family members of patients younger than age 55 years was made in less than 1% of inpatient medical records (15). More optimistic data reveal that hospital compliance with smoking cessation guidelines for patients with an acute myocardial infarction has improved, with an estimated 84% receiving counseling (16). The data reveal that what is achievable in clinical trials does not generally translate into everyday practice, a phenomenon otherwise known as the “treatment gap.”

Strategies for Integration of Comprehensive Risk Reduction into Cardiologic Practice

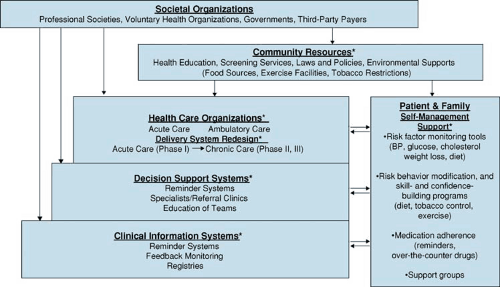

The treatment gaps observed in cardiovascular risk reduction are also seen in the management of a variety of other chronic diseases. Cardiovascular risk factor modification is a long-term process that requires patient and physician to assume a chronic disease management paradigm that demands significant modification in lifestyle and adherence to pharmacologic interventions. For such regimens to be successful, a multidimensional and comprehensive approach requires careful and proactive consideration. The Chronic Care Model (17) described by Wagner for primary care practices can also be applied to cardiovascular disease risk management, given the inherent challenges of any long-term therapy that often involves multiple interventions. The Chronic Care Model has six elements (Table 14.2), which can be applied to cardiovascular disease, with risk factor modification the cornerstone for successful management of the chronic disease (Fig. 14.2).

Role of Societal Organizations

Health care organizations do not function in a vacuum, but are influenced philosophically, intellectually, economically, and legally by a variety of societal organizations, including professional societies (e.g., the American College of Cardiology), voluntary health organizations (e.g., the American Heart Association), governments at the local, state or province, and national levels, and third-party payers, either private or public. One such influence is the development of standards or guidelines on what constitutes good care. A large number of clinical practice guidelines to address the spectrum of issues related to CVD have been published by professional groups, most notably the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. These guidelines are comprehensive and designed to be useful in practice settings while incorporating the most recent evidence from the research arena. Included in these guidelines are the evaluation and treatment of patients with (18,19,20) and without diagnosed CVD (19,20); CVD and its risk factors in minorities (21), women (22), and patients with the metabolic syndrome (23), diabetes (24), hyperlipidemia (7), and hypertension (25); individuals who smoke (26); persons older than the age of 75 years (27); and children and adolescents (28,29). A comprehensive guide to improving cardiovascular health at the community level is also available targeted at health care providers, public health practitioners, and health policy

makers (30). These guidelines provide a wealth of evidence-based information and are invaluable resources for health care organizations, practicing clinicians, and other stakeholders in the areas of CVD treatment and prevention.

makers (30). These guidelines provide a wealth of evidence-based information and are invaluable resources for health care organizations, practicing clinicians, and other stakeholders in the areas of CVD treatment and prevention.

TABLE 14.2 Six Elements of the Chronic Care Model | ||

|---|---|---|

|

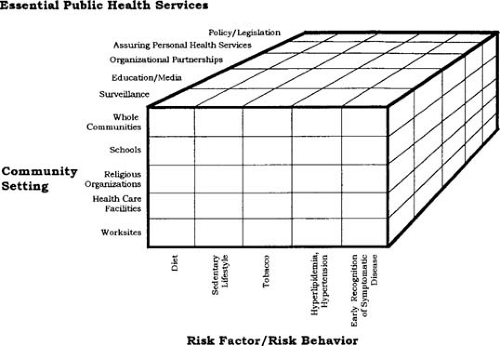

Community Resources

The Chronic Care Model recognizes the need for patients and family to be care providers in a system of self-management. Aiding in this is a community environment that assists both patients and care providers to enable patients to modify lifestyles, access acute and ambulatory health care services, and adhere to complex treatment regimens. The American Heart Association Guide to Improving Cardiovascular Health at the Community Level (30) provides evidence-based recommendations for community-based strategies for CVD reduction (Fig. 14.3). These guidelines specifically address population-based changes in diet, sedentary lifestyle, and tobacco use, diagnosis and treatment of hyperlipidemia and hypertension, and early recognition of symptoms of myocardial infarction and stroke. Although they are applicable to low-risk children and adults, the guidelines have general relevance to patients and providers who would benefit from an environment conducive and supportive

of efforts to control risk factors. Such an environment may include surveillance of the heart disease burden, health education programs, screening services, and government policies supporting healthier foods, exercise facilities, tobacco-free air, and so on. These resources are found in whole communities, but also in places where people work, study, worship, and receive health care.

of efforts to control risk factors. Such an environment may include surveillance of the heart disease burden, health education programs, screening services, and government policies supporting healthier foods, exercise facilities, tobacco-free air, and so on. These resources are found in whole communities, but also in places where people work, study, worship, and receive health care.

TABLE 14.3 Treatment Rates at Discharge and at One-Year Follow-Up | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||