Question

What is your clinical assessment and what action should be taken at this juncture?

Comment

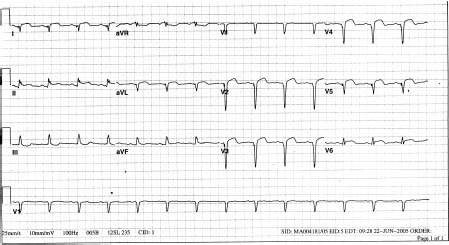

The clinical presentation of persistent chest pain, nausea, weakness, dyspnea and diaphoresis coupled with characteristic ECG findings of elevated ST segments in more than two contiguous leads points to the diagnosis of an acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) of the anterior wall. The objectives of management at this stage are: (a) relief of symptoms with oxygen, morphine and an intravenous beta-blocker, and (b) rapid restoration of nutrient blood flow through the occluded coronary artery. As to the latter, time is of the essence! There are three therapeutic options:

- fibrinolytic therapy with streptokinase or intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (e.g. reteplase, tenectoplase or alteplase)

- primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)

- facilitated PCI.

Although fibrinolytic therapy is a proven effective strategy for reducing both morbidity and mortality in STEMI,1 there is now persuasive Level A evidence that primary PCI achieves better short-term (4–6 weeks) and long-term (6–18 months) outcomes when compared to fibrinolytic therapy.2 The outcomes measured were mortality rates, non-fatal reinfarction, strokes and major bleeds.

Timing and access must be taken into consideration. The earlier the arrival of the patient (less than 30 minutes), the less the advantage of PCI over fibrinolysis becomes apparent, especially if there is an anticipated time delay in transporting the patient across town to another facility.3 Conversely, many studies have shown the superiority of primary PCI for those patients who require emergency transport to another facility especially if the “time to balloon” can be achieved within 60–90 minutes.4 The degree of risk has not always been carefully integrated in trial analyses. However, it is safe to assume that those patients at higher risk, as with any of the established interventions, benefit the most. Our patient is an ideal candidate for primary PCI. He is at moderate to high risk (anterior myocardial infarction with evidence of some cardiac decompensation), he appears within the recommended window of 30–60 minutes and has no major contraindications.

Should there be no ready access to an angiographic facility, the preferred treatment would be aspirin 150–350mg followed immediately by fibrinolysis with, in this particular case, a tissue plaminogen activator. An anti-thrombin agent is added to help maintain patency of the culprit artery. It should be borne in mind that the combined use of fibrinolytics, antiplatelets and antithrombin agents reduces mortality rates and non-fatal reinfarction at the expense of an increased risk of major and minor bleeding.5 While low molecular weight heparin offers better outcomes than weight-adjusted unfractionated heparin, the net clinical benefit (i.e. adjusted for major bleeding rates) is less apparent because of the higher rates of bleeding with low molecular weight heparin.6 The presence of pulmonary rales and an S4 gallop rhythm in this patient with a suspected large anterior wall infarction mitigates against intravenous beta-blocker therapy as long as the chest pain can be ameliorated with oxygen and morphine.7

What about opting for a strategy of immediate throm-bolysis followed by PCI? This is so-called facilitated PCI. Theoretically, this approach offers quicker patency of the culprit artery on the way to restoration of coronary blood flow with PCI. The 2007 ACC/AHA focused update no longer recommends facilitated PCI for STEMI.7 Recent analyses have shown a worse outcome with facilitated PCI compared to primary PCI for STEMI.8

Case history continued

On the basis of the PCI-CURE study, our patient is quickly administered two antiplatelet agents: 150 mg of chewable aspirin and 300 mg clopidogrel loading dose.9 He is quickly transported to a cardiovascular center situated within one mile of the index hospital. At 90 minutes post symptom onset, a paclitaxel drug-eluting stent (DES) is deployed at the site of an occlusive thrombus in the proximal left anterior descending artery. His angiogram also demonstrates an old distal occlusion of a dominant right coronary artery and a 30% lesion in the obtuse marginal branch of the circumflex artery. He tolerates the procedure without incident. His blood pressure is now 132/70 and he is not in heart failure. He is started on a well-established secondary prevention regimen of an oral beta-blocker (metoprolol 50 mg bid), an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor in the form of ramipril starting at 5 mg qam and a HMG Co-A reductase inhibitor (atorvastatin) at 20 mg qhs.1 Aspirin at 81 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg daily are continued.

The following day he complains of a sharp left parasternal pain exacerbated by movement, coughing and/or taking a deep breath. On his ECG we now see that the ST segment elevation has failed to descend following deployment of the stent and there is new ST elevation in leads II and III (Fig. 74.2). Furthermore, the tachycardia has returned despite the institution of a beta-blocker and clear lung fields. Physical examination confirms the presence of a pericardial friction rub. His blood pressure remains stable at 130/80. His internal jugular veins are not distended.

Figure 74.2 Note the new ST elevation in lead II with further ST depression in AVR-all consistent with an acute pericardial reaction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree