Acute Mesenteric Ischemia

PRATEEK K. GUPTA and GIRMA TEFERA

Presentation

A 78-year-old woman with known history of atrial fibrillation, on warfarin, presents to the emergency department with a sudden onset of severe abdominal pain and emesis for the past few hours. She has never had similar symptoms. The patient is retired, but fairly active around the house, and able to climb two flights of stairs without shortness of breath. She is a nonsmoker, nonalcoholic, with no prior abdominal operations and has no history of gastric ulcers. On physical examination, she is awake, alert, and oriented. She is tachycardic (heart rate of 111 per minute) with a blood pressure of 89/60 mm Hg. She has abdominal tenderness but no guarding, rigidity, or rebound tenderness. Her peripheral pulses are all palpable.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis at this stage includes several etiologies of acute abdominal conditions. These include peptic ulcer disease with and without perforation, acute pancreatitis, acute cholecystitis, acute diverticulitis, acute urologic conditions including infections, acute bowel obstruction, and acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI), besides others.

Workup

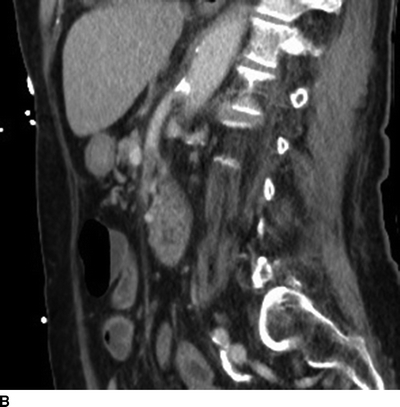

In our patient, laboratory findings revealed a normal creatinine, elevated WBC count, and a subtherapeutic INR. CT of the abdomen with IV and PO contrast was obtained to assess for etiology of acute abdomen. This shows (Fig. 1A and B) emboli in the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). The bowel has some wall thickening but no pneumatosis coli, which suggests necrotic bowel. Portal venous gas is also not seen, which would also have been suggestive of bowel necrosis.

FIGURE 1 CT scan showing thrombus in proximal SMA by (A) coronal and (B) sagittal views.

Discussion

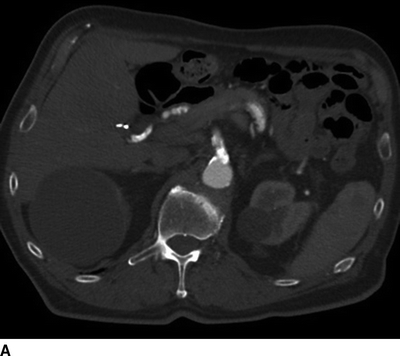

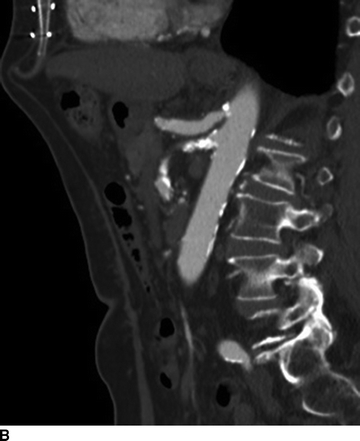

AMI can be due to an emboli lodging in the SMA (50% of cases), thrombosis of an atherosclerotic lesion at the origin of the mesenteric vessel (20%), mesenteric venous thrombosis (10%), and nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (20%). Emboli are most commonly from the heart and tend to lodge in the SMA given the angle of its takeoff and almost parallel course to the aorta. They tend to progress to 5 to 10 cm beyond the takeoff to the level of the middle colic and jejunal branches where the diameter is narrower (Fig. 1A and B). Thrombus typically forms at the ostia of vessels in the setting of previous chronic mesenteric ischemia resulting in acute-on-chronic mesenteric ischemia (Fig. 2A and B). Rarely, thrombus may form in a setting of dissection into the SMA (3).

FIGURE 2 CT scan showing highly calcified proximal SMA with occlusion in (A) coronal and (B) sagittal views.

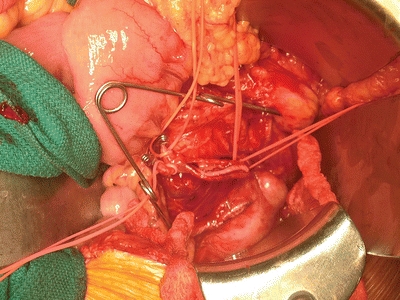

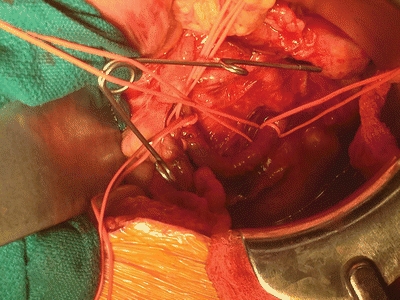

FIGURE 3 Open surgical exposure of the SMA showing a dissection flap after arteriotomy performed.

AMI, if untreated, typically leads to bowel infarction due to compromise in intestinal blood flow. Patients classically present with abdominal pain out of proportion to physical examination. Nausea and emesis are frequent. In patients with SMA emboli, history of atrial fibrillation or heart murmur is frequent, while in thrombotic AMI, patients may have had symptoms of chronic mesenteric ischemia such as postprandial pain, constipation/diarrhea, and weight loss. The abdominal exam is not very impressive in the initial stages; however, peritonitis sets in soon leading to an acute abdomen. Leukocytosis is common. Lactate may be elevated with acidosis and a base deficit in cases of bowel necrosis.

The workup of a patient with acute abdominal conditions includes laboratory investigations, limited abdominal ultrasound (US), and other imaging modalities such as plain abdominal x-rays and computed tomographic scans. The degree of the workup depends on the stability of the patient and presence of acute peritoneal signs. An exploratory laparotomy is warranted in patients with generalized peritonitis, who present with abdominal tenderness and rebound tenderness suggesting generalized peritonitis.

Laboratory investigations such as basic metabolic and hematologic panels are usually very generic and none conclusive; therefore, the results have to be taken within the context of the physical exam. Abdominal US is a readily available, low-cost test that could help screen for acute cholecystitis, appendicitis, renal stones, and hydronephrosis. An abdominal vascular US exam can also be undertaken; however, this can be limited by the presence of bowel gas. A plain abdominal x-ray is a valuable test to identify bowel obstruction or perforated viscus.

In cases of AMI, imaging is needed for confirmation of clinical diagnosis. Abdominal x-ray may show an ileus-like pattern. CT scan with IV contrast is the most common mode of diagnosis and shows filling defect in the visceral vessels suggestive of thrombosis or embolism. Other imaging modalities may include duplex US and magnetic resonance imaging; however, these are rarely obtained in patients presenting with an acute abdomen. Catheter-based angiography may be needed if CT is not available.

Diagnosis and Treatment

This patient with AMI needs to be resuscitated and started on therapeutic heparin anticoagulation to prevent extension of the clot burden. Nasogastric tube and urinary catheter are placed. Emergent operative intervention is needed to assess the bowel and perform SMA revascularization.

In cases of acute-on-chronic mesenteric ischemia that also typically involves the SMA, either retrograde stent through the open abdomen or a bypass, either antegrade from the supraceliac aorta or retrograde from the iliac vessels, is indicated. Rarely, percutaneous lysis is performed in select centers if the disease process is in the early stages without concern for bowel ischemia.

It is important to involve the patient and his or her family in the discussion regarding goals and expectations given the high morbidity and mortality in this disease process. It is imperative to have a clear understanding of patient preferences prior to going to the operating room in case there is large segment of bowel necrosis that would make the patient total parenteral nutrition (TPN) dependent for life.

Surgical Approach

Given the patient has AMI due to an SMA embolus, she is taken to the operating room under general anesthesia and laid supine on the table. If possible, the procedure is performed on a table capable of fluoroscopy in case completion angiogram is needed. The patient is prepped from nipples to knees, taking care to prep a leg in the field, in case saphenous vein needs to be used for a bypass.

The abdomen is opened through a midline vertical incision, and the peritoneum is entered. A self-retaining retractor system is helpful for exposure. The bowel is examined to assess for viability. If a large segment of the bowel is completely necrotic, consideration should be given for stopping the procedure based on the patient’s preoperative wishes.

The transverse colon is retracted superiorly and the fourth portion of the duodenum mobilized to the ligament of Treitz. The SMA is identified at the root of the mesentery. If calcified, it may be directly felt; otherwise the middle colic artery can be used to trace down to it; or if the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) is identified, the artery is medial to it. In cases of an embolus, most often the SMA is palpable proximally with a sharp cutoff in pulse present. The vessel is exposed and controlled at that point using vessel loops (Fig. 4). The branches are also controlled. The patient is therapeutically anticoagulated and activated clotting times checked. In cases of emboli, a transverse arteriotomy is made on the vessel, and balloon catheters are passed both in an antegrade and retrograde fashion until no more clot is retrieved and brisk bleeding is seen. The arteriotomy can then be closed using simple interrupted or mattress stitches. The vessel and bowel mesentery are checked for pulses, and Doppler is used to hear the signals. If there is concern for branch viability due to persisting embolus or dissection due to the embolectomy catheter, an angiogram is helpful in assessing the collaterals and in deciding if the particular branch needs to be revascularized by directly cutting down on it and tacking the dissection flap. The bowel mesentery is then closed with interrupted absorbable stitches. The bowel is reexamined to assess for viability. If necrotic bowel is seen, it needs to be resected and in most cases left in discontinuity. The gallbladder should also be examined to assess for ischemia. Thorough irrigation is performed. Temporary abdominal closure is done with a planned “second-look” operation after 24 hours.

FIGURE 4 Proximal exposure of the SMA is done with vessel loops, as illustrated here.