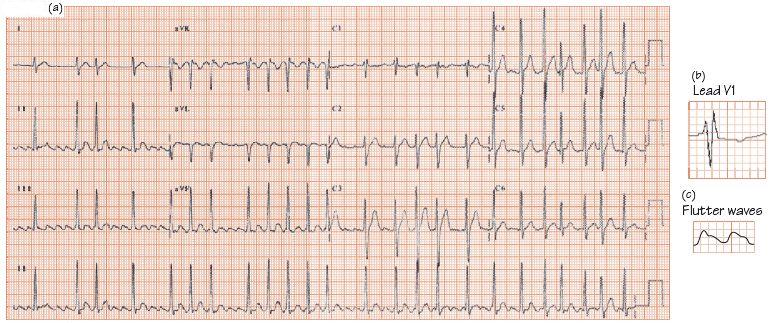

Fig. 20.2 Heart failure. The patient had mild effort breathlessness and then suddenly became much more breathless. (a) The ECG shows a well organized atrial arrhythmia (look at the rhythm strip and Fig. 20.2c), probably atrial flutter, and a fast QRS rate, overall around 140–150 b/min. The QRS axis is rightward shifted (equidominant R wave lead I, i.e. R = S wave, and dominant R wave lead II and III), according to the computer, +89°. (b) The QRS complex is unremarkable aside from a RSR′ pattern in lead V1, indicating partial right bundle branch block (RBBB). Normal T waves. Heart failure is often provoked by the onset of atrial flutter/fibrillation. A secundum atrial septal defect (with pulmonary to systemic blood flow of 4 : 1) underlay the heart failure, the clues here being right axis deviation, and partial RBBB.

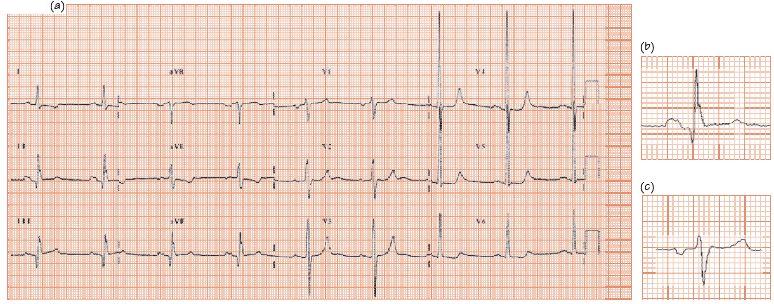

Fig. 20.3 (a) Left atrial enlargement ((b) bifid P wave in lead II, (c) late negative deflection in lead V1) marked left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) with repolarization changes. The standard leads show unremarkable voltages, the chest leads greatly increased (S V3 = 18 mm, R V4 = 43 mm, together 61 mm, markedly raised). Laterally (I, aVL, V5 and V6) ‘reverse-tick’ ST depression (‘LVH-associated repolarization changes’, in old terminology ‘LVH with strain’). The patient had critical aortic stenosis, though from the ECG could equally have hypertensive heart disease.

The cause of new onset severe breathlessness can usually be identified from the history, physical examination, and simple tests including the ECG, spirometry/peak flow, chest X-ray and blood gases. Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) has an increasingly important role.

Acute left ventricular failure The patient is usually obviously breathless especially on lying flat, and is cold, sweaty, tachycardic (proportional to severity) and cyanosed, and in life-threatening pulmonary oedema, pink frothy sputum. The causes are:

- Acute myocardial infarction (AMI), common, suspected from typical cardiac quality pain (retrosternal chest discomfort, ‘tightness’, ‘squeezing’ or ‘heavy’ sensation, sometimes radiating to the neck, and/or left or both arms) with sweating and/or nausea. The ECG maybe ‘classic’, i.e. ST elevation (Fig. 20.1); however, equally and not infrequently, the ECG may show ‘only’ ST depression, left bundle branch block, or less specific signs despite a new myocardial infarction (MI) being present. One should always have a high index of suspicion that a new MI underlies acute left ventricular failure (LVF).

- Multivessel coronary disease without major infarction, not uncommon. The ECG usually shows widespread ST depression, which normalize with LVF treatment. Subsequent troponin release is often low, and left ventricle (LV) function, once LVF has resolved, is reasonable. Angiography confirms multivessel coronary artery disease and guides treatment.

- Decompensated chronic heart failure, often from a remote MI, with a more recent event, such as atrial fibrillation, fluid retention from a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent (NSAIA), or anaemia, etc. The ECG shows evidence of old damage, e.g. anterior lead Q waves, left bundle branch block, etc.

- Aortic stenosis, often first suspected from finding left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) on the ECG (as the murmur is very quiet during acute LVF); the differential diagnosis of pulmonary oedema with an ECG showing LVH includes hypertensive heart disease, and ischaemically mediated heart failure.

Pulmonary embolus There are four distinct presentations of a pulmonary embolus with different ECG findings (Table 20.1).

Arrhythmias It is unusual for tachyarrhythmias to cause heart failure, unless they are very fast, there is damage to LV function, or severe valvar heart disease is present. The commonest arrhythmias causing heart failure are atrial fibrillation in a patient with pre-existing LV dysfunction. Occasionally atrial fibrillation results in very fast ventricular heart rates, and breathlessness; the commonest cause of this is the Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome.

Pneumonia Is a common cause of breathlessness. Patients experience malaise, fever, and cough, breathlessness and occasionally chest pain or haemoptysis. The ECG is either normal, or shows the results of sepsis – sinus tachycardia, sometimes with non-specific ST changes. Pneumonia increases the risk of MI in subsequent weeks threefold.

Airways disease Asthma patients have acute attacks of wheezing with breathlessness. The ECG shows sinus tachycardia during the episodes, proportional to severity. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, usually (not always) smoking related, results in a gradual decline in effort tolerance over years. The clinical course can be punctuated by acute exacerbations. The ECG may show the consequences of pulmonary arterial hypertension (right atrial enlargement, right axis deviation, dominant R wave in lead V1, due to right ventricular hypertrophy or to right bundle branch block) though is often unremarkable.

Pneumothorax This results in sinus tachycardia.

Dysfunctional breathing Is a common cause of breathlessness. Sinus tachycardia may (infrequently) occur; low levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the blood increase the pH, altering the physiology of repolarization. Widespread ST changes can occur, ST flattening, and ST depression being the most common. Clearly these changes also occur with coronary disease, or left ventricular dysfunction from many causes, e.g. cardiomyopathy, so these diseases may need to be ruled out before concluding the ECG changes are due to hyperventilation alone.

How to analyse the ECG in an acutely breathless patient

There are many different ways to analyse the ECG in the setting of acute breathlessness, and everyone needs to find the approach that suits them best. One approach to this situation (the same as in most illnesses) is as follows:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree