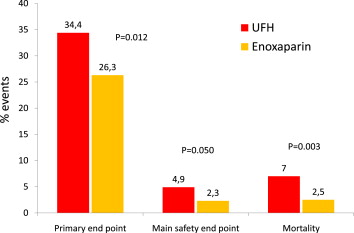

Intravenous enoxaparin did not reduce significantly the primary end point (p = 0.06) compared with unfractionated heparin (UFH) in the randomized Acute Myocardial Infarction Treated with primary angioplasty and intravenous enoxaparin Or unfractionated heparin to Lower ischemic and bleeding events at short- and Long-term follow-up (ATOLL) trial. We present the results of the prespecified per-protocol analysis excluding patients who did not receive the treatment allocated by randomization or received both enoxaparin and UFH. We evaluated all-cause mortality, complication of myocardial infarction, procedural failure, or major bleeding (primary end point) and all-cause mortality, recurrent acute coronary syndrome, or urgent revascularization (main secondary end point). Baseline and procedural characteristics were well balanced between the 2 treatment groups. Of 910 randomized patients, 795 patients (87.4%) were treated according to the protocol with consistent anticoagulation using intravenous enoxaparin (n = 400) or UFH (n = 395). Enoxaparin reduced significantly the rates of the primary end point (relative risk [RR] 0.76, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.62 to 0.94, p = 0.012) and the main secondary end point (RR 0.37, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.63, p <0.0001). There was less major bleeding with enoxaparin (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.01, p = 0.050) contributing to the significant improvement of the net clinical benefit (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.3 to 0.74, p = 0.0002). All-cause mortality was also reduced with enoxaparin (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.74, p = 0.003). In conclusion, in the per-protocol analysis of the ATOLL trial, pertinent to >87% of the study population, enoxaparin was superior to UFH in reducing ischemic end points and mortality.

In the Acute Myocardial Infarction Treated with primary angioplasty and intravenous enoxaparin Or unfractionated heparin to Lower ischemic and bleeding events at short- and Long-term follow-up (ATOLL) trial, intravenous (IV) enoxaparin compared with unfractionated heparin (UFH) significantly reduced clinical ischemic outcomes without differences in bleeding, improving the net clinical benefit of patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). However, the 17% reduction of the primary end points, death, complication of myocardial infarction (MI), procedural failure, or major bleeding, did not reach statistical significance. A unique feature of the ATOLL study design was to realize a head-to-head comparison between the 2 anticoagulants by excluding patients who had received any anticoagulation before randomization and mandating no crossover to a different anticoagulant after randomization. In addition, similar antiplatelet therapy was used in both groups. Nine of 10 patients were treated consistently with the same anticoagulant according to the study protocol, but a minority of patients received both anticoagulants (protocol violation). The objective of the present study was to perform the prespecified per-protocol analysis excluding patients who received >1 heparin at any point during the period of revascularization and follow-up (protocol violation) using an approach similar to the initial intent-to-treat analysis. The goal of this per-protocol analysis was to examine whether the “pure” head-to-head comparison between the 2 anticoagulants as designed in the study protocol confirmed the initial hypothesis of a superiority of enoxaparin over UFH in primary PCI.

Methods

ATOLL was an international, randomized, open-label trial led by the Academic ACTION study group ( www.action-coeur.org ) evaluating IV enoxaparin versus IV UFH in patients undergoing primary PCI for ST elevation myocardial infarction. The study protocol has been described in detail elsewhere. All patients assigned to enoxaparin by randomization received an IV bolus of 0.5 mg/kg enoxaparin without anticoagulation monitoring as previously described. After the procedure, prolongation of anticoagulation was left to the physician’s discretion, but if anticoagulation was continued, prophylactic doses were recommended (enoxaparin 40 mg/day subcutaneously), unless full anticoagulation was required. In patients randomly assigned to UFH, UFH was administered according to the current guidelines. If continued after the procedure, venous thromboembolic prophylactic UFH anticoagulation was recommended unless full anticoagulation was required. All patients received aspirin (75 to 500 mg/day), thienopyridines, and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors according to local practice. Clinical follow-up was performed at 30 ± 2 days. Radial access and the use of arterial closure devices after femoral access were allowed. Femoral sheath removal in the absence of closure devices was authorized with an activated clotting time from 150 to 180 seconds in the UFH group and immediately after the end of PCI in the enoxaparin group. All technical aspects concerning mechanical reperfusion were left to the discretion of the treating clinician.

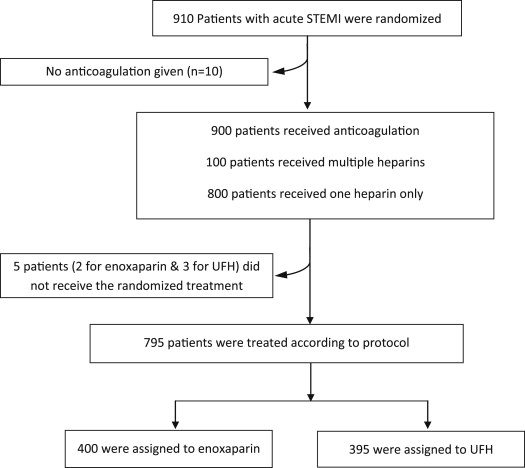

The main analysis of the trial as previously published was based on the intent-to-treat population of all patients randomized, irrespective of study treatment given or whether any study treatment was even administered. The prespecified per-protocol population studied here was defined as anticoagulant-naive patients at the time of randomization, who were administered at least 1 dose of the study drug before PCI according to the randomization procedure, and who were treated with the same anticoagulant treatment after PCI if anticoagulation was continued. Patients who did not receive any anticoagulant at the time of PCI were excluded from the per-protocol analysis (n = 10). Patients who did not receive the randomized treatment or who were switched to another anticoagulant after PCI irrespective of the dosage regimen (curative or preventive) were excluded from the per-protocol analysis ( Figure 1 ).

All end points have been defined. Briefly, the primary end point was the occurrence during the first 30 days of follow-up of the composite of all-cause mortality, complication of MI, procedural failure, or major bleeding. The main secondary efficacy end point was a composite of any death, recurrent acute coronary syndrome, or urgent revascularization. The main safety end point was the occurrence of major bleeding unrelated to coronary artery bypass graft during the hospital stay, according to the SafeTy and Efficacy of Intravenous Enoxaparin in Elective Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (STEEPLE). The net clinical benefit end point was prespecified as the combination of death, complication of MI, or major bleeding. Mortality was defined as death from any cause.

Continuous variables are summarized as mean and SD or as median and quartiles in the case of non-Gaussian distribution and were compared by t test or Mann-Whitney test. All qualitative variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages and were compared using chi-square test for frequency comparisons or Fisher’s exact probability test when the criteria of chi-square were not fulfilled. Relative risk and 95% confidence interval were calculated for end points. The per-protocol analysis was performed as the intent-to-treat analysis on the new population as aforementioned. Time to event was compared using log-rank test. All tests were 2-sided, with a significance level fixed at 5%. No adjustment was made for multiplicity. All analyses were performed using the SAS software (version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

In the ATOLL trial, none of the 910 patients received an anticoagulant before randomization. Compliance with interactive voice response system-indicated study drug before and during catheterization was 96% (n = 433) and 97% (n = 444) for IV enoxaparin and IV UFH, respectively. Patients who were administered both heparins numbered 8 (1.8%) and 6 (1.3%) before and during catheterization, respectively, and 42 (9.3%) and 58 (12.6%) during the whole study period in the enoxaparin and UFH groups. Finally, 400 patients (89%) in the enoxaparin group and 395 patients (86%) in the UFH group were consistently treated across the whole hospital stay with enoxaparin or UFH according to the randomized allocation of treatment, except 2 patients in the enoxaparin group and 3 patients in the UFH group, who did not receive the study drug ( Figure 1 ).

Baseline and procedural characteristics were well balanced between the 2 treatment groups in this per-protocol analysis ( Table 1 ). Patients were mainly men, 1 of 10 had signs of heart failure, and almost 3% presented with resuscitated cardiac arrest and/or cardiogenic shock. Primary PCI was effectively performed in most patients. Intense antiplatelet therapy was used. Average anticoagulant treatment duration was slightly longer with enoxaparin.

| Variables | ENOX (n = 400) | UFH (n = 395) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 59 (51–70) | 60 (52–70) | 0.83 ∗ |

| Age (>75 yrs) | 75 (18.8) | 64 (16.2) | 0.34 |

| Gender (Women) | 86 (21.5) | 81 (20.5) | 0.73 |

| Weight (kg) | 75 (67–85) | 76 (68–86) | 0.42 ∗ |

| Medical history | |||

| Previous CABG | 4 (1) | 5 (1.3) | 0.75 ∗ |

| Previous cancer | 23 (5.8) | 25 (6.3) | 0.73 |

| Previous COPD | 8 (2) | 16 (4.1) | 0.09 |

| Diabetes | 54 (13.5) | 60 (15.2) | 0.49 |

| Dyslipidemia | 164 (41) | 158 (40) | 0.77 |

| Hypertension | 180 (45) | 179 (45.3) | 0.93 |

| Previous MI | 24 (6) | 36 (9.1) | 0.10 |

| Previous PAD | 12 (3) | 20 (5.1) | 0.14 |

| Previous PCI | 29 (7.3) | 47 (11.9) | 0.03 |

| Current smoker | 181 (45.3) | 180 (45.6) | 0.93 |

| Previous stroke | 12 (3) | 8 (2) | 0.38 |

| Known renal failure | 10 (2.5) | 8 (2) | 0.65 |

| Hemodynamic condition before sheath insertion | |||

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 75 (65–85) | 75 (65–88) | 0.24 ∗ |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 139 (120–156) | 140 (120–160) | 0.38 ∗ |

| Killip class (II, III, and IV) | 27 (6.8) | 43 (10.9) | 0.04 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 7 (1.8) | 12 (3) | 0.23 |

| Cardiac arrest | 5 (1.3) | 12 (3) | 0.08 |

| Concomitant treatments | |||

| Aspirin | 391 (97.8) | 378 (95.7) | 0.10 |

| ACE inhibitors | 316 (79) | 300 (75.9) | 0.30 |

| β Blockers | 360 (90) | 330 (83.5) | 0.007 |

| Insulin | 45 (11.3) | 58 (14.7) | 0.15 |

| Statin | 361 (90.3) | 338 (85.6) | 0.04 |

| GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 313 (78.3) | 333 (84.3) | 0.03 |

| Clopidogrel | 380 (95) | 367 (92.9) | 0.22 |

| Clopidogrel loading dose (>600 mg) | 101 (25.3) | 106 (26.8) | 0.61 |

| Clopidogrel loading dose (mg) | 600 (300–675) | 600 (300–750) | 0.24 ∗ |

| Clopidogrel maintenance dose during hospitalization (mg) | 75 (75–150) | 75 (75–150) | 0.13 ∗ |

| Clopidogrel maintenance dose after discharge (mg) | 75 (75–75) | 75 (75–75) | 0.67 ∗ |

| Treatment duration (mean ± SD) | 4.1 ± 3.4 | 3.7 ± 2.9 | 0.02 |

| Procedural characteristics | |||

| PCI | 345 (86.3) | 345 (87.3) | 0.65 |

| CABG | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 1.00 ∗ |

| Radial access | 285 (71.3) | 269 (68.1) | 0.33 |

| Culprit artery | 0.09 ∗ | ||

| LM | 5 (1.5) | 3 (0.9) | |

| LAD | 149 (43.3) | 137 (39.7) | |

| Circ | 39 (11.3) | 60 (17.4) | |

| RCD | 151 (43.9) | 143 (41.4) | |

| CABG | 0 (0) | 2 (0.6) | |

| Embolectomy/thrombectomy device | 167 (48.4) | 159 (46.1) | 0.54 |

| Stent implanted in patients who underwent PCI | 329 (95.4) | 327 (94.8) | 0.72 |

| Drug-eluting stent | 56 (17) | 55 (16.8) | 0.94 |

There was a significant 24% reduction of the primary end point among patients treated with enoxaparin compared with UFH (p = 0.012; Figure 2 ). There was also a robust 64% reduction of mortality (p = 0.0034; Figure 2 ) and a 67% reduction of death or resuscitated cardiac death (p = 0.001), 2 important prespecified secondary end points. The enoxaparin group also showed a significantly lower rate of the main secondary end point evaluating ischemic outcomes ( Table 2 and Figure 3 ). Death or complication of MI and the net clinical benefit were significantly reduced with enoxaparin ( Table 2 and Figure 3 ). All the secondary ischemic end points showed consistent superiority of enoxaparin over UFH. The safety profile also favored enoxaparin over UFH ( Figure 2 ). The composite of major and minor bleeding unrelated to coronary artery bypass graft was significantly reduced, by 35% (p = 0.046), with enoxaparin ( Table 2 ).