Ventricular Enlargements

6.1. Background

The term ventricular enlargement (VE) refers to both hypertrophy of the myocardial mass of the ventricles as well as dilation of the cavity, and may include a combination of both conditions.

Electrogenesis of the ECG morphology seen in VE is more frequently the result of hypertrophy than cavity dilation, the opposite of which is true in atrial enlargement. Mild or even moderate VE may not change in the ECG.

Sometimes a patient may live for many years with heart disease with VE before ECG abnormalities are present.

VE is best detected with echocardiography; however, a diagnosis of VE using ECG provides more prognostic value.

We will now outline the basic concepts and straightforward ECG criteria for the diagnosis of VE.

6.2. Right Ventricular Enlargement

Right ventricular enlargement (RVE) is mainly found in congenital cardiopathies, right valvular heart diseases, and chronic and acute cor pulmonale (pulmonary embolism and decompensation in chronic cor pulmonale).

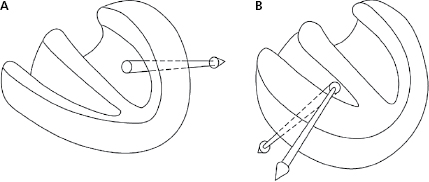

6.2.1. Mechanisms of the Electrocardiographic Changes [A]

- Figure 6.1 shows how RVE reverses the dominant forces of left ventricle (A), changing the direction to the right and sometimes forwards, and other times backwards (B) due to the increase in RV mass and to the slowing of conduction at the level of the RV wall, because in spite of RVE the mass of LV still is greater than the RV mass.

- Often it is associated with a delayed activation of the right ventricle due to the block of impulse at the proximal level (classic right bundle branch block [RBBB]).

- Changes in repolarization in the form of negative ST-T are seen in some severe cases of RVE. Cases of decompensation of chronic cor pulmonale or pulmonary embolism are often mostly secondary to right ventricular dilation, which modifies the direction of the repolarization

6.2.2. Repercussions of These Changes in the ECG

6.2.2.1. Horizontal Plane

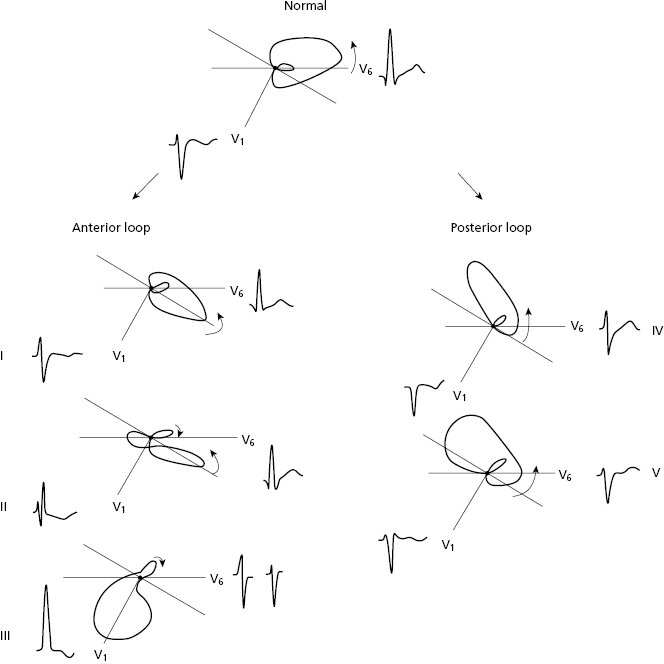

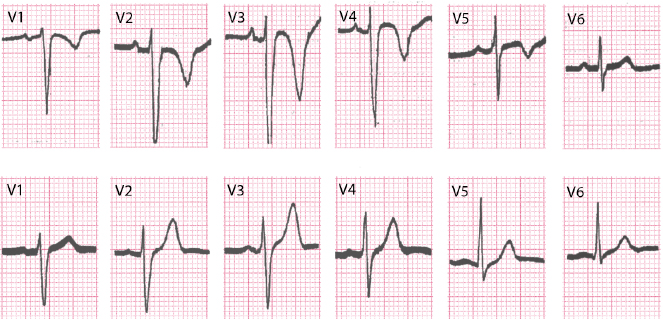

The modification in the QRS loop due to vectorial changes induced by RVE explain the QRS morphology in the HP, which moves either forwards and to the right, or backwards and to the right.

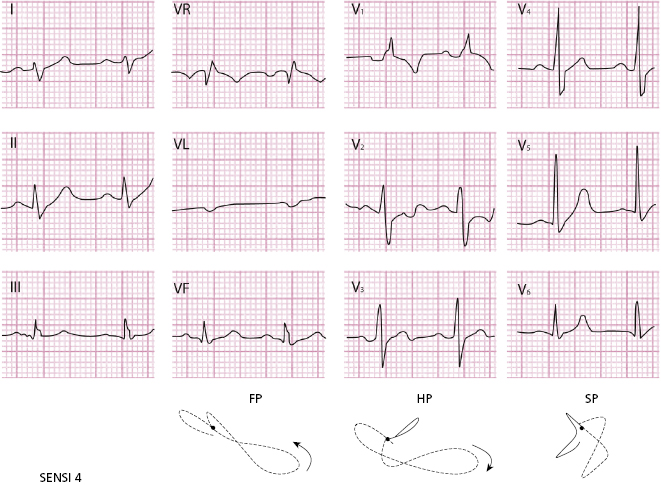

In the former (Fig. 6.2), vectorial changes induced by RVE cause the QRS loop to move forwards while maintaining the same rotation (I), then it rotates in 8 (II), and finally it can rotate the entire loop clockwise and forward (III). On other occasions the loop moves backwards, but with a large part to the right (IV and V).

Based on these patterns, in V1 a pattern from low voltage QS  till to RS or R only (

till to RS or R only ( ) may be seen in V1, with always a pattern with big S (

) may be seen in V1, with always a pattern with big S ( ,

,  ) in V6 (Fig. 6.2).

) in V6 (Fig. 6.2).

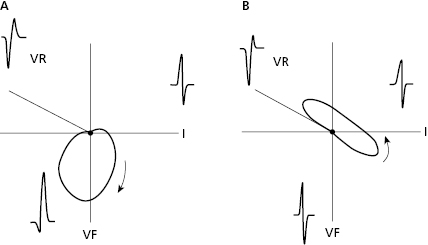

6.2.2.2. Frontal Plane

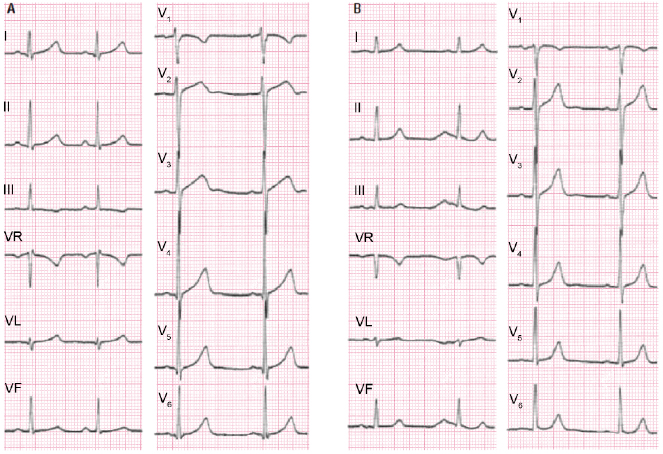

The morphology of QRS, according to the rotation and direction of the loop, presents right ÂQRS (RS in I and qR in VF) (A), or the ÂQRS is indeterminate (S1 S2 S3) (B) (Fig. 6.3).

6.2.3. Diagnosis of RVE in Clinical Practice [B]

The most commonly used criteria, which are very specific but not with low sensitivity, are the following:

- ÂQRS ≥110° (R < S in I).

- V1 = R/S > 1, and/or S in V1 <2 mm, and/or R ≥ 7 mm.

- V6: R/S ≤ 1 and/or S in V5–V6 > 7 mm.

- P wave of the RAE.

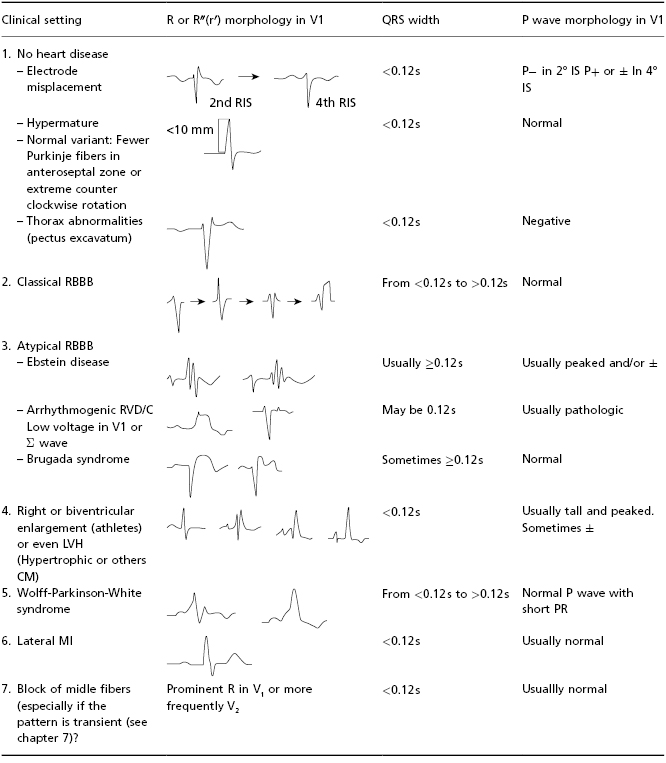

- It is important to make a differential diagnosis with all the processes that might originate a high R or rSr′ in V1 (Table 6.1).

- In cases of QS morphology in V1, the associated signs (S in V6, ÂQRS, P wave) facilitate the diagnosis of RVE (see before, and Fig. 6.4C).

- The signs of RVE, especially R in V1 of high voltage, may regress, at least partially, after surgery in patients with congenital heart diseases.

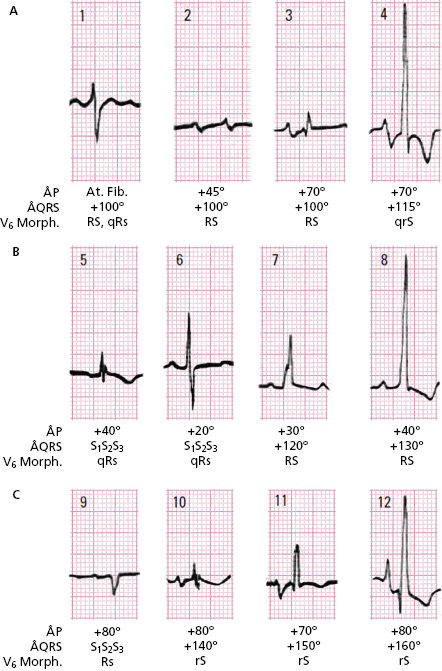

6.2.4. ECG Morphologies in Different Types of RVE

6.2.4.1. Morphologies in V1 and Other ECG changes According to the Severity and Etiology of the Hypertrophy

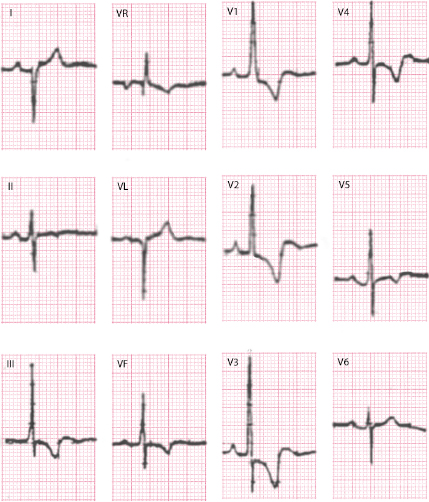

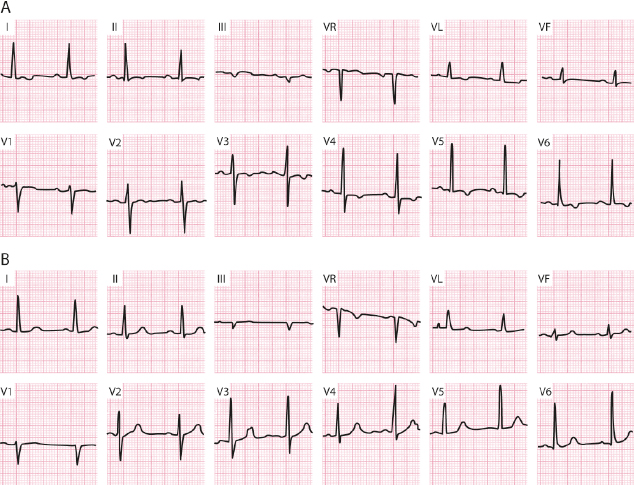

Figure 6.4 shows examples of three groups of patients (A); valvular heart diseases (B); congenital heart diseases; and (C), cor pulmonale. In these three cases we may see patterns that present, with rs or rsr′, or even QS in patients with cor pulmonale, to only R with a strain-type pattern. In addition, we see that ÂQRS is always to the right or S1 S2 S3, and that ÂP is to the right in valvular heart disease cor pulmonale, while it is somewhat to the left in congenital heart diseases (P congenitale) (Fig. 5.2C).

Figures 6.5 to 6.8 show examples of some congenital and acquired heart diseases (cor pulmonale) that present characteristic ECG patterns of RVE. Consult Sections 17.1 and 17.2 in Chapter 17, where the ECG in patients with valvular and congenital heart diseases is discussed.

6.2.4.2. ECG Changes Due to Acute Dilation of the Right Cavities [C]

Acute dilation of the right cavities may be seen in patients with decompensation of chronic cor pulmonale and in patients with pulmonary embolism.

In the first group of patients, the HP may show negative, reversible T waves that may be deep, and increased S waves until V6, with ÂQRS more to the right (Fig. 6.9).

In severe cases of pulmonary embolism, evident ECG changes are often found (Chapter 17). The most noticeable changes include: (a) sinus tachycardia; (b) negative T waves in right precordial leads; and (c) appearance of advanced RBB (Fig. 15.4), or SI QIII morphology with negative TIII (McGinn-White sign) (Fig. 15.3). The ECG may appear normal in mild or moderate pulmonary embolism.

6.2.5. Differential Diagnosis

A. Differential Diagnosis of the Morphology of Right VE with a Prominent R or r′ in V1

Table 6.1 shows the different clinical contexts in which prominent R or r′ (R′) in V1 is observed.

Table 6.1 Presence of prominent R or r′ in V1: Differential diagnosis. [F]

B. Differential Diagnosis of RVE with QS Morphology in V1 [D]

These cases must be distinguished from other processes that present QS in V1, such as left branch block (LBB) and septal infarction. The presence of the associated ECG signs (S in V6, right ÂQRS or S1 S2 S3, and P wave of RAE) facilitate the diagnosis of RVE (Fig. 6.3).

6.3. Left Ventricular Enlargement

- Left ventricular enlargement (LVE) is mainly seen in acquired heart diseases (aortic valve disease, arterial hypertension, cardiomyopathies (including ischemic cardiomyopathies, and genetically induced cardiomyopathies), and some types of congenital heart diseases (aortic stenosis, aortic coarctation, and fibroelastosis).

- Generally, hypertrophy predominates dilation in LVE. This is more frequent in the presence of cardiomyopathy) and in heart diseases with diastolic overload, of LV (e.g. aortic regurgitation) in VI.

6.3.1. Mechanisms of ECG Changes [E]

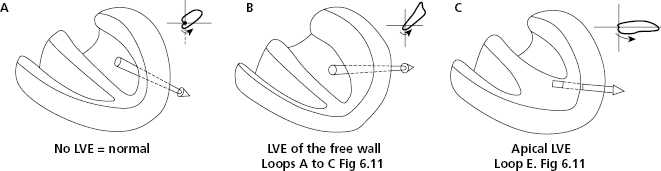

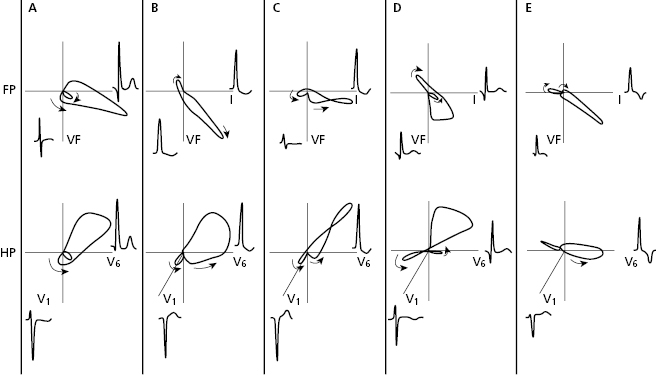

- Figures 6.10 and 6.11 show that in LVE the vectorial forces of the free wall of LV that is the part of LV that grows the most, are directed more backwards (B), and upward and to the left (ÂQRS more or less to the left). In LVE of the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (MH) with apical predominance the vectorial forces move less backward (Fig. 6.10C).

- The LVE is often associated with specific degrees of left branch block (LBBB).

- Repolarization changes with some ST depression, and a negative and asymmetrical T are caused more by the clinical course of the disease than the degree of overload (systolic or diastolic).

- With the passage of time, especially in severe cases, the pattern referred to as ‘strain pattern’ with a negative ST-T appears. These changes are in part secondary to the depolarization changes (hypertrophy). A certain degree of ischemia is often also involved, as well as the effect of certain drugs such as digitalis, for example (primary factor), originating mixed pattern (Fig. 6.13C) in which ST depression or a very negative T predominate.

6.3.2. Repercussions of the Changes in the ECG

6.3.2.1. Changes in the FP and HP

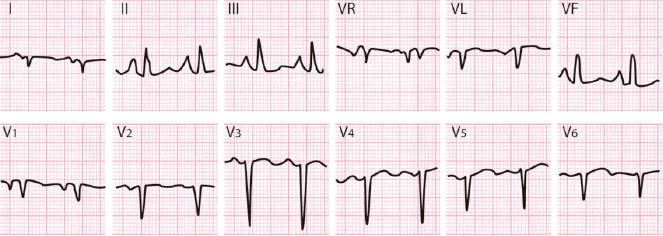

Figure 6.11 shows the QRS loops in the FP and HP and the ECG morphologies in normal patients (A), patients with mild to moderate LVE (B), and those with severe LVE (C). In HM, with septal hypertrophy deep ‘q’ waves may be seen, and in the case of hypertrophy with apical predominance, very negative T waves may be found (D and E).

6.3.3. The Diagnosis of LVE in Clinical Practice [G]

- The voltage criteria, which are very specific (>90%) although with less sensitivity (20–50%) of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), include:

- Cornell criterion: R VL +SV3 >24 mm in men and >20 mm in women.

- Sokolow criterion: SVI+RV5-6 ≥35 mm.

- VL criterion: VL ≥11 mm, or ≥16 mm in the presence of supero-anterior hemiblock.

- Cornell criterion: R VL +SV3 >24 mm in men and >20 mm in women.

- The presence of strain-type repolarization alterations and/or evidence of LAE or atrial fibrillation reinforce the diagnosis, especially in the presence of voltage criteria.

- The associations between these criteria are the basis for diagnostic scores, the most well known being the Romhilt–Estes score (Bayés de Luna, 2012a) (Table 6.2).

- The presence of dilation of LV combined with hypertrophy is suggested by (a) the voltage of V6 is greater than or equal to that of V5; (b) IDT ≥ 0.07 s; and (c) relatively low voltage in the FP compared to the HP.

Table 6.2 Romhilt-Estes score. There is left ventricular enlargment if 5 or more points are obtained. Left ventricular enlargement is probable if the sum is 4 points.

| A. Criteria based on QRS modifications | |

| 1. Voltage criteria | 3 points |

One of the following should be present:

| |

| 2. AQRS at −30° or more to the left | 2 points |

| 3. Intrinsicoid deflection in V5–V6 ≥ 0.05 | 1 point |

| 4. QRS duration ≥0.09 s | 1 point |

| B. Criteria based on ST-Tchanges | |

1. ST-T vector opposite to QRS ( ) without digitalis ) without digitalis | 3 points |

2. ST-T vector opposite to QRS ( ) with digitalis ) with digitalis | 1 point |

| C. Criteria based on P wave abnormalities | |

| 1. Negative terminal P mode in V1 ≥ 1 mm in depth and 0.04sec in duration | 3 points |

6.3.4. ECG Morphologies in Specific Types of LVE

6.3.4.1. Small Differences between the Normal ECG and Mild LVE [H]

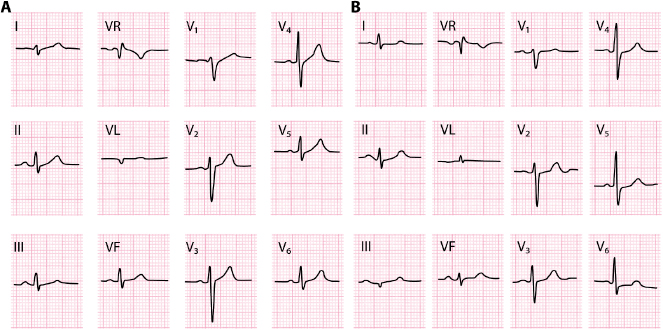

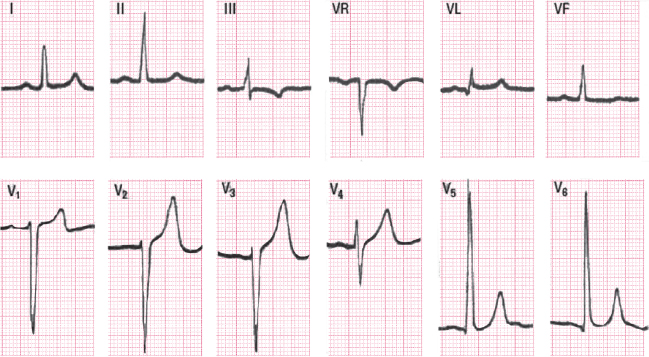

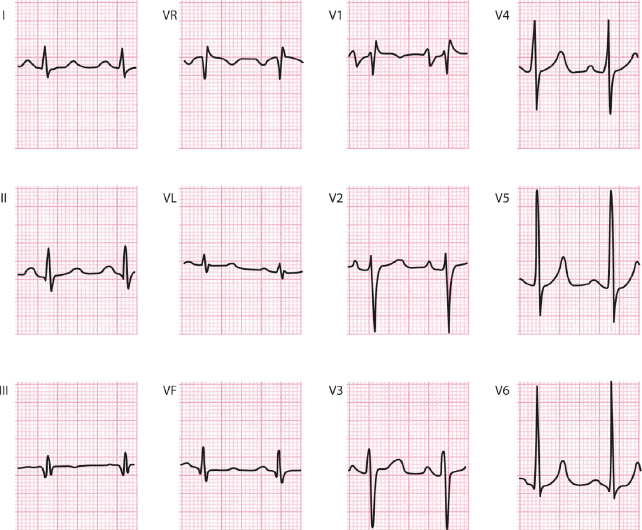

Occasionally, the diagnosis of LVE based on an echocardiogram may not be made by ECG, or may only be indicated by subtle ECG changes that may even be seen in healthy individuals. These changes, however, are a little different from the completely normal ECG seen in normal people. Figure 6.12 shows the rectified ST and the symmetry of the T wave in II, III, VF, and V5–V6 in cases of a patient with moderate HTA (B) compared with that of a healthy individual showing very similar QRS but with a normal ST-T (upsloping and asymmetrical) (A).

It is important to bear in mind that these subtle changes may be variants of normal patterns, especially in menopausal women and in the elderly. These cases must therefore be studied more closely because they could correspond to mild LVE or even ischemic heart disease, especially if accompanied by mild ST depression (<1 mm). A good history taking and clinical examination are necessary, in addition to complementary testing (e.g. stress test, echocardiogram), before making the definitive diagnosis.

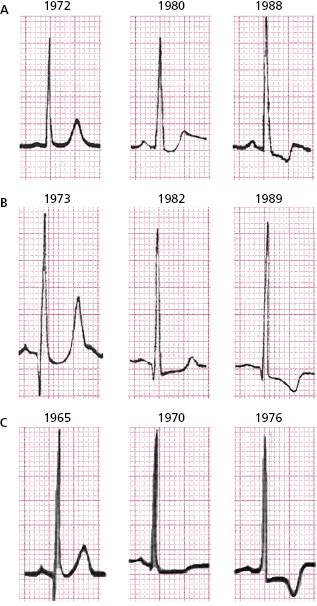

6.3.4.2. Changes During the Clinical Course in LVE [I]

Figure 6.13 shows the clinical course of a patient with LVH evolving to strain-pattern (negative ST-T with asymmetrical branches), both in aortic stenosis (systolic overload) (A), and in aortic regurgitation (diastolic overload) (B). The latter case may present more often a small q wave. C shows the appearance of a pattern of strain with an added primary factor (digitalis and ischemia). See the rectified depression of the ST depression and the more symmetrical and deeper T wave (see above).

Figure 6.14 illustrates the ECGs of a patient with LVH, showing severe aortic regurgitation in a young person that had not been longstanding. Voltage criteria for LVE are presented, with qR in V5-6, a rectified ST segment and a symmetric and tall T wave. Figure 6.15 shows the ECG of a 45-year-old man with severe longstanding aortic stenosis presenting LVH with strain.

6.3.4.3. Regression of LVE Pattern

The signs of repolarization suggesting LVH in the ECG in patients with hypertension who show LVH in the echocardiogram may regress with adequate treatment, and have a good prognosis. An example is shown in Figure 6.16. The signs of LVE may also regress after surgical correction of some valvular and congenital heart disease.

6.3.5. Differential Diagnosis in LVE [J]

- Advanced left bundle branch block (LBBB)

- In LVE the QRS never measures 120 ms or more, although many cases of severe LBBB present associated LVE.

- LVE often shows signs that are suggestive of concomitant first-degree LBBB (missing q in V6 and I and even missing r in V1 with QRS < 120 ms).

- In LVE the QRS never measures 120 ms or more, although many cases of severe LBBB present associated LVE.

- Septal infarction

- A missing r in V1–V2 may make the differential diagnosis difficult with septal infarction using ECG alone. Favors septal infarction negative/symmetrical T wave in V1–V2.

- Wolff–Parkinson–White pre-excitation type I and II

- This has a delta wave and PR is short.

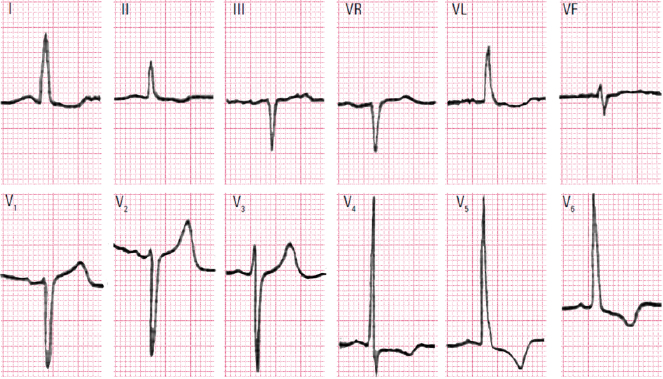

6.4. Biventricular Enlargement (Fig. 6.17) [K]

It is sometimes difficult to diagnose because the presence of one type of enlargement may mask the other.

Diagnostic criteria include:

- High R in V5-6 with right ÂQRS or S1 S2 S3.

- High R in V5-V6 with RS in V1-V2.

- QRS with normal voltage but with considerable repolarization alterations.

- Low-voltage QRS in V1, evident S in V2 and R or Rs in V5-6 with right ÂQRS or S1 S2 S3. (Fig. 6.17).

- The P wave may present signs of right and/or left atrial involvement (Fig. 5.4), or atrial fibrillation.

Self-assessment

A. List the electrophysiologic changes that explain the ECG morphologies of RVE.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree