From Symptoms to the ECG

ECGs in the Presence of Precordial Pain or Other Symptoms

15.1. Chest Pain

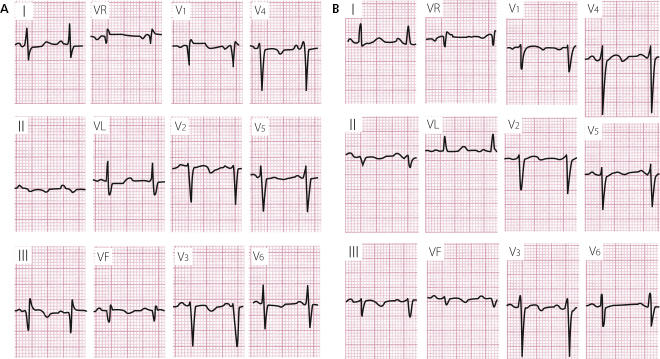

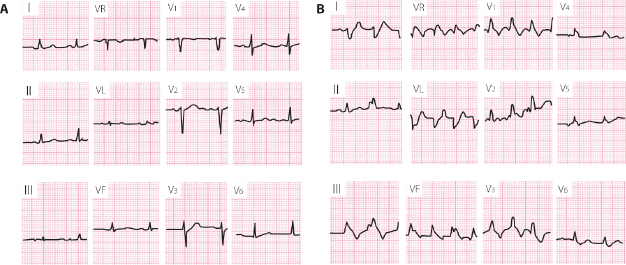

15.1.1. Ischemic Heart Disease Versus Pericarditis or Other Causes of Chest Pain

Patients with chest pain in the emergency room may have of three types of origin:

- Clearly ischemic pain, in which case medical history and ECG changes (Chapter 9) together with biomarkers are the key to confirming the diagnosis. [A]

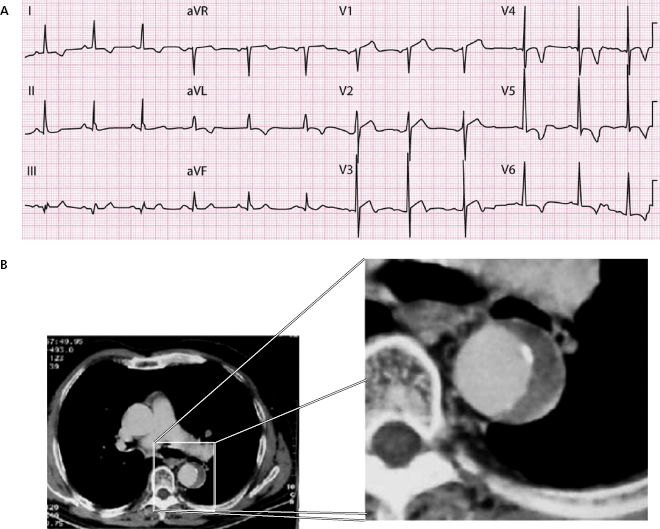

- Non-ischemic pain that may or may not be cardiovascular. The former includes pathologies which are usually benign, such as pericarditis, or very dangerous, such as aortic dissection. A detailed medical history together with the evaluation of a clinical examination, together with the ECG and the imaging techniques are all very important in reaching a definitive diagnosis. Table 15.1 shows the keys to the differential diagnosis between acute coronary syndromes (ACS), pericarditis, miocarditis, pulmonary embolism and aortic dissection, the five most important cardiovascular pathologies involving chest pain. Along with a description of the ECG, the relevance of the medical history and biomarkers are also outlined.

Non-cardiovascular pathologies include: (i) pain due to chest wall and skeletal muscle problems (very frequent); (ii) respiratory pain (pneumothorax, pleuritis, etc.); (iii) pain in the digestive tract, and colecistitis; and (iv) psychogenic pain (anxiety, hyperventilation, etc.). It should be remembered that hyperventilation may change the ECG, especially inducing a flat/negative T wave (Fig. 4.25). [B]

- Chest pain in 25–30% of patients who arrive at hospital is difficult to diagnose. The course of the episode of pain must be followed and the ECG findings and, if necessary, additional tests are needed before clarifying these cases.

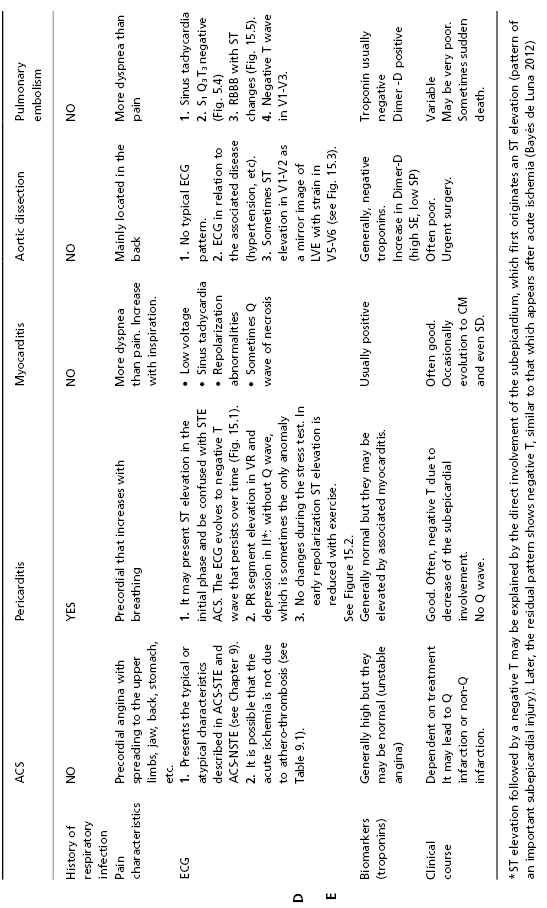

Table 15.1 Differential diagnosis with ACS, pericarditis, aortic dissection and pulmonary embolism: role of ECG

15.2. Acute Dyspnea

The presence of acute dyspnea may be explained by the following processes as outlined below. The ECG findings are very important in the diagnostic deduction of the causal process.

- Left ventricular failure. Edema or subedema of the lungs during the course of ACS or fast tachyarrhythmia most likely indicates atrial fibrillation or, less frequently, ventricular tachycardia. It is accompanied by anginal pain in ACS and sometimes also in tachyarrhythmias without ischemic heart disease. The medical history and the ECG findings are very important in the diagnosis. [C]

- Pulmonary embolism. There is more dyspnea than pain. Risk factors must be identified, if they exist.

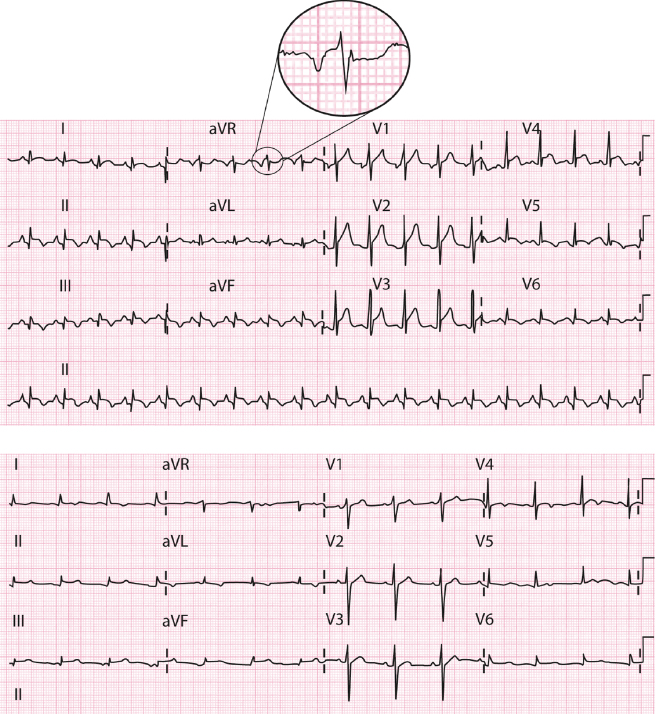

The ECG is very important because it may show typical ECG abnormalities such as: SI QIII TIII negative pattern (McGinn-White sign) (Fig. 15.4) and the appearance of advanced RBBB pattern (Fig. 15.5). Where there is an abrupt appearance of symptoms and the very frequent presence of sinus tachycardia (with the exception of the elderly with sinus dysfunction) it is very important to suspect the diagnosis. The additional testing and imaging techniques are particularly important.

- Decompensated chronic cor pulmonale. This is generally due to a presentation of an additional respiratory infection in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The physical examination, medical history, oxygen saturation, ECG and biomarkers are important in the diagnosis (Fig. 6.5).

- Episode of bronchial asthma. This may be seen in young people. The medical history and physical examination are key.

The ECG in patients without associated heart disease may be relatively normal (sinus tachycardia and peaked P with the P axis to the right).

- Pneumothorax. The medical history and chest XR exam are decisive.

The ECG may also be useful. Often it is normal, but in the left pneumothorax a right ÂQRS and low voltage in precordial leads may be seen. Sometimes, reversible and rarely striking, repolarization disturbances may occur.

- Dyspnea as an equivalent to angina. In the presentation of acute ischemic attack cardiopathy, dyspnea may be the protagonist as the equivalent to anginal pain.

The medical history and ECG together with biomarkers can usually clarify the situation.

- Chronic heart failure may present an exacerbation of the symptoms of dyspnea due to either the clinical course of the disease or the association of some added factor previously mentioned, especially tachyarrhythmia, respiratory infection, or pulmonary embolism.

- Decompensated chronic cor pulmonale. This is generally due to a presentation of an additional respiratory infection in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The ECG, the clinical course, and the biomarkers (NT-pro-BNP) are very important in reaching the correct diagnosis and most accurate prognosis.

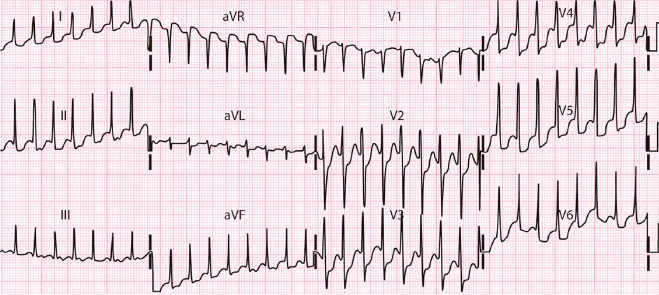

15.3. Palpitations

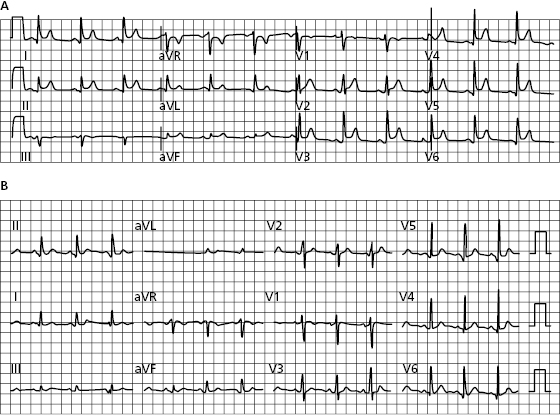

If the patient presents with palpitations it may be possible to identify a specific arrhythmia based on the medical history and physical examination, but the ECG is the definitive tool confirming the diagnosis if the patient presents with arrhythmia, or suggesting it if is not present (e.g. WPW morphology, Brugada pattern, P± wave in II, III, VF). It is important to know that in the presence of rapid tachyarrhythmias the ST may present depression usually with ST upsloping. However, sometimes even in young people without heart disease, the ST may present, at least in some leads, an horizontalized ST depression (Fig. 15.6). In the absence of arrhythmia during examination, medical history plays a crucial role. A correctly taken medical history can lead to the following conclusions: [F]

- The patient presents a sensation of early isolated contractions that leave a void or give a sensation of the heart missing a beat. This is very likely due to extrasystoles.

- The problem is the abrupt appearance in the elderly of the fast and irregular arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation) or regular arrhythmia (probably atrial flutter). In these cases, sometimes the patient complains of chest discomfort more than palpitations, and if the crisis lasts a long time may be considered as a possible ACS.

In the case of regular paroxysmal tachycardia that appears in a young person, it is probably a reentrant tachycardia with the circuit exclusively in the AV junction, if the patient feels the palpitation in the neck. If episodes began during childhood, it is probably paroxysmal tachycardia due to reentry of the AV junction with involvement of an accessory pathway. At the same time, the ventricular rate in the case of atrial flutter can vary when some F waves are blocked, while in paroxysmal tachycardia it is fixed and generally above 150–160 bpm (Figs 11.7 to 11.10). Figure 11.11 shows an algorithm used for differential diagnosis with regular tachycardias with narrow QRS, based on careful study of the ECG findings.

If in the physical examination and ECG no arrhythmia is detected despite suggestive data in the medical history, additional tests must be carried out starting with a Holter recording and stress test. Other tests may also be necessary (Bayés de Luna 2011, 2012).

15.4. Syncope

15.4.1. Concept

This is the abrupt and transitory loss of consciousness caused by a sudden reduction in cerebral blood flow. It may be a benign symptom or a marker of serious arrhythmia with a risk of sudden death. [G]

15.4.2. The Mechanism of Syncope Involves the Following:

- (A) Neuromediated (>50% of cases) with participation of a vagal reflex. It includes coughing syncope, miccional syncope, syncope by vein puncture, orthostatic syncope, and syncope due to hypersensitivity in the carotid sinus. It may be vasodepressive (the most common type), cardioinhibitory (that occurs rarely but sometimes with long pauses requiring pacemaker implantation), or mixed.

- (B) Cardiac origin. The most frequent types are due to tachyarrhythmias of bradyarrhythmias. The most serious syncopes are those provoked by VT/VF because they can produce sudden death in the first syncope (ischemic heart disease, heart failure, genetically induced heart disease) (see Chapter 17).

- Generally, syncope due to bradyarrhythmias (severe sinus bradycardia or sinoatrial or AV block) are preceded by a sensation of dizziness or instability, and the first episode does not usually result in sudden death. The more serious cases appear during the course of acute infarction (RC occlusion before exiting of the AV node artery). It is important to consider the possibility of syncope due to bradyarrhythmia in patients who present advanced branch block, especially LBB or bifascicular block and if PR is long (see Bayés de Luna, 2012). Naturally, the presence of trifascicular block (RBB alternating with two hemiblocks) requires, like many types of syncope associated with bradyarrhythmia, pacemaker implantation.

Syncope due to blood flow obstruction (e.g. aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, myxoma) can also occur.

- Generally, syncope due to bradyarrhythmias (severe sinus bradycardia or sinoatrial or AV block) are preceded by a sensation of dizziness or instability, and the first episode does not usually result in sudden death. The more serious cases appear during the course of acute infarction (RC occlusion before exiting of the AV node artery). It is important to consider the possibility of syncope due to bradyarrhythmia in patients who present advanced branch block, especially LBB or bifascicular block and if PR is long (see Bayés de Luna, 2012). Naturally, the presence of trifascicular block (RBB alternating with two hemiblocks) requires, like many types of syncope associated with bradyarrhythmia, pacemaker implantation.

- (C) Neurological syncope. This type of syncope or feeling of instability may appear in situations related to transitory cerebral ischemic disturbances.

15.4.3. How to Choose the Best Management Approach

The medical history (family history of sudden death or vagal syncope in childhood), the type of presentation at rest or during exercise, the physical examination together with the ECG (presence of active or passive arrhythmia and branch block, especially if they are of high risk) (see Chapter 17), an echocardiogram, and tilt test (useful to confirm vagal syncope) may all be used to determine the mechanism of syncope and select the best treatment. In athletes, exercise syncope is a marker of poor prognosis and requires an exhaustive study with coronarography and imaging techniques, among others, to rule out ischemic heart disease, coronary and aortic anomalies, and genetically induced heart disease (see Bayés de Luna, 2011). [G]

Self-assessment

A. How many types of chest pain may be encountered in the emergency room? How is ischemic pain diagnosed?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree