Workup of Patient with Atherosclerotic Arterial Vascular Disease: Focus on Risk Factor Modification

SUROVI HAZARIKA and ADITYA M. SHARMA

Presentation

A 72-year-old woman with past medical history of hypertension and diabetes mellitus type II presents with a 3-month history of right great toe nonhealing wound. She also complains of pain in her right calf while walking more than approximately 100 feet. Pain is relieved within 3 minutes when she stops walking. She also has a 40-pack-year smoking history. She currently takes the following medications: hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg daily and metformin 500 mg twice daily. Her vital signs are normal. Physical examination is unremarkable except for nonpalpable pulses in the dorsalis pedis and the posterior tibial arteries bilaterally, with dopplerable signals.

Differential Diagnosis

Most common differentials for ulcers in the foot include venous stasis ulcers, neurotrophic ulcers, and arterial (ischemic) ulcers. Usually, venous stasis ulcers are seen on the inner aspect of the legs, above the ankles, and may affect one or both legs. They are commonly seen in patients who have venous stasis, varicose veins, or prior history of deep venous thrombosis. Neurotrophic ulcers are usually seen in patients with diabetes or other peripheral neuropathies and arise at points of increased pressure and weight bearing. Arterial ulcers are most often seen on the heels, on the tips of the toes, or between pressure points, associated with other signs and symptoms of poor arterial circulation in the affected leg such as claudication or poor pulses in the lower extremities.

Workup

The ankle-brachial index (ABI) is the most common noninvasive screening tool used for diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease (PAD). ABI is calculated as the ratio of the highest brachial systolic pressure to the highest systolic pressure in either the dorsalis pedis or the posterior tibial artery, measured in each lower extremity using a handheld Doppler. A normal resting ABI does not preclude a diagnosis of PAD, and where clinical suspicion exists, postexercise ABI should be done. A normal ABI ranges from 1.00 to 1.40, and abnormal values are defined as those ≤0.90. ABI values of 0.91 to 0.99 are considered “borderline,” and values greater than 1.40 indicate noncompressible arteries. In patients with long-standing diabetes and advanced age, ABI can be nondiagnostic due to noncompressible vessels. In such cases, toe-brachial index should be used to establish the diagnosis of lower extremity PAD. Other modalities that are also helpful for diagnosis of PAD include pulse volume recording, continuous wave Doppler ultrasound, duplex ultrasound, magnetic resonance angiography, CT angiography, as well as contrast angiography.

Case Continued

The patient underwent ABI testing. Her resting ABI was 0.64 in the right and 0.76 in the left, indicating moderate arterial occlusive disease. Subsequently, she underwent a CT aortogram with runoff to the lower extremities, which showed severe long segment right superficial femoral artery severe stenosis and occluded proximal right popliteal artery.

Discussion

Lower extremity PAD is estimated to affect up to 8 to 12 million Americans. Up to 40% of these patients suffer from poor quality of life due to impaired walking ability, nonhealing wounds, and need for amputation. However, all of these patients have high risk for cardiovascular mortality and morbidity. PAD is a polyvascular disease. Sixty to ninety percent of patients with PAD also have coronary artery disease (CAD), and up to 25% have significant carotid artery stenosis. Over a 5-year period, only 1% to 2% of claudicants and asymptomatic patients develop critical limb ischemia (CLI). However, the overall 5-year mortality rate among patients all with PAD is 15% to 30% (75% of which is cardiovascular), and risk of nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke is 20% at 5 years. Patients with CLI such as our patient have much worse cardiovascular outcomes with an annual CV mortality of 25% and annual amputation rate of 25%. This cardiovascular morbidity and mortality can be reduced significantly with use of appropriate cardiovascular medications as well as aggressive risk factor modification.

Focus on Cardiovascular Prevention Medications

Antiplatelet Therapy

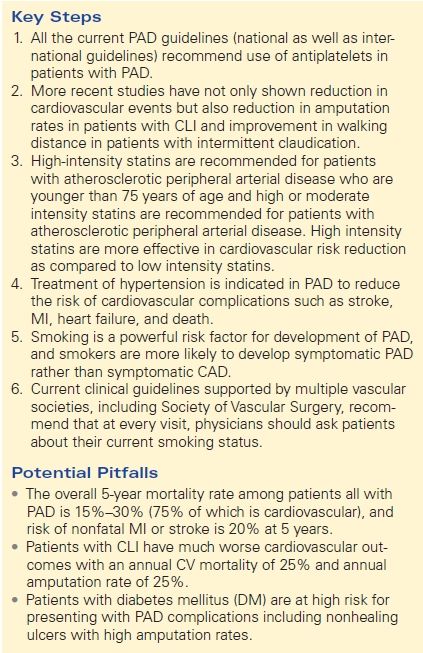

The main benefits of antiplatelet therapy in patients with arterial vascular disease are from secondary cardiovascular prevention as supported by a 20% to 30% risk reduction of nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or vascular death as shown by a meta-analysis of the Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. In addition, in a subgroup analysis of the CAPRIE trial, clopidogrel was found to have a modest advantage over aspirin in reducing the incidence of stroke, MI, or vascular death in patients with symptomatic PAD. All the current PAD guidelines (national as well as international guidelines) recommend use of antiplatelets in patients with PAD. The ACC/AHA guidelines strongly recommend antiplatelet therapy (aspirin in daily doses of 75 to 325 mg or clopidogrel 75 mg) to reduce the risk of MI, stroke, and vascular death in individuals with symptomatic lower extremity PAD, including those with intermittent claudication or critical limb ischemia, prior lower extremity revascularization (endovascular or surgical), or prior amputation for lower extremity ischemia (class Ia). Antiplatelet therapy (aspirin in daily doses of 75 to 325 mg or clopidogrel 75 mg) is also recommended to reduce the risk of MI, stroke, and vascular death even in individuals with asymptomatic lower extremity PAD (class IIa). However, the benefit of antiplatelet therapy is not as well proven in asymptomatic patients as it is in those with symptomatic PAD such as claudication or those requiring vascular procedures or with CLI.

Statin Therapy

Several studies have focused on the outcome of PAD with treatment with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins). A subgroup analysis of PAD patients within the Heart Protection Study demonstrated a 22% relative risk reduction in the rate of first major vascular event regardless of the initial baseline low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels. More recent studies have not only shown reduction in cardiovascular events but also reduction in amputation rates in patients with CLI and improvement in walking distance in patients with intermittent claudication. High-intensity statins are more effective in cardiovascular risk reduction compared with low-intensity statins. The current ACC/AHA guidelines recommend that all patients younger than 75 years with atherosclerotic PAD should be on a high-intensity statin (lowering LDL cholesterol [LDL-C] by ≥50%). Patients older than 75 years of age should be on at least a moderate-intensity statin (lowering LDL-C by approximately 30% to 50%) (Tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 1. Medical Management of Arterial Vascular Disease