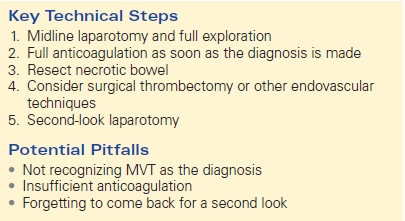

Mesenteric Venous Occlusive Disease

MICHELLE MUELLER

Presentation

A 48-year-old man with a past medical history of gastroesophageal reflux disease but no previous surgeries presents to the emergency department complaining of abdominal pain. He has had intermittent abdominal pain for years, but the symptoms have dramatically worsened over the last 2 weeks. The onset of pain occurs approximately 30 minutes after meals and lasts for hours, and is now associated with nausea and vomiting. The patient denies any weight loss, melena, or hematochezia. A recent upper endoscopy was unremarkable, and colonoscopy showed benign polyps.

On physical examination, the patient is noted to be afebrile and hemodynamically stable. The examination reveals the abdomen to be soft and mildly distended with moderate tenderness to palpation, but without peritoneal signs. There are no hernias. The white blood cell count is 7000, and hemoglobin is 40 mg/dL. The electrolyte levels, liver function tests, amylase, lipase, and lactate levels are normal. To further evaluate the abdominal pain, a computed tomography (CT) scan with oral and intravenous contrast is ordered.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for abdominal pain without peritonitis is extensive. Chronic abdominal pain narrows the differential, yet it remains lengthy. Possible diagnoses in this case include gastroesophageal reflux disease, inflammatory bowel disease, peptic ulcer disease, biliary colic, chronic cholecystitis, chronic pancreatitis, partial small bowel obstruction, tumor, chronic mesenteric ischemia, and mesenteric venous thrombosis (MVT).

Workup

CT scanning is an important part of the evaluation of abdominal pain. The addition of intravenous contrast to a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis aids in the diagnosis of venous thrombosis, aneurysms, bowel ischemia, and bleeding. CT scan with venous phase contrast has greater than 90% accuracy in establishing the diagnosis of MVT. Important findings on the scan are thrombus, superior mesenteric vein dilation, target or “halo” sign, thickened bowel wall, and presence of collateral veins within the mesentery.

CT Scan

CT Scan Report

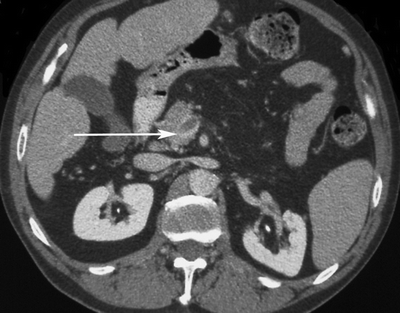

The CT scan reveals MVT (Fig. 1). There is mesenteric stranding and a filling defect in the superior mesenteric vein ringed with contrast, “halo” sign (arrow) (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 1 CT scan with mesenteric vein thrombosis. Arrow highlights thrombus, with enhancing halo.

FIGURE 2 CT scan showing thrombosed superior mesenteric vein. Arrow highlights thrombus with halo.

Diagnosis and Treatment

MVT is a broad term that includes thrombosis of the inferior mesenteric vein, superior mesenteric vein, splenic vein, or portal vein. MVT is responsible for approximately 2% to 15% of all cases of acute intestinal ischemia. MVT obstructs venous return, which can lead to edema of the bowel wall, distention, and eventual infarction. MVT is difficult to diagnose initially because of the typical insidious onset and subtle early clinical findings. Early symptoms are produced by congestion of the bowel and are visceral in character. Patients may present with signs and symptoms that are nonspecific and vague, including crampy abdominal pain, abdominal distention, nausea, anorexia, malaise, ascites, diarrhea, gastrointestinal bleeding, and pain out of proportion to examination. About half of patients will have leukocytosis; an elevated lactate is unusual. Delays in diagnosis are common and contribute to the reported high morbidity and 15% to 40% mortality.

The traditional separation of MVT into primary or secondary categories is arbitrary. All patients with MVT should be regarded as harboring a hypercoagulable state. The hypercoagulability may be endogenous and related to a defined abnormality in the coagulation system (e.g., protein C deficiency, protein S deficiency, antithrombin deficiency, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, lupus anticoagulant, factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation). Alternatively, the hypercoagulable state producing MVT may result from other processes, such as intra-abdominal inflammation (pancreatitis, diverticular disease, peritonitis, appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease), trauma, portal hypertension, intra-abdominal or hematologic malignancy, polycythemia vera, myeloproliferative disorders, splenomegaly, oral contraceptives, cirrhosis, or even severe dehydration.

It is more relevant clinically to categorize MVT on the basis of duration of symptoms as well as whether portal or splenic vein thrombus is present. MVT can present acutely with a more fulminant course lasting only days or as a chronic condition (arbitrarily defined as lasting at least 4 weeks). Acute MVT more often results from small mesenteric vein branch involvement and is more difficult to diagnose with CT scanning or duplex ultrasound because the larger mesenteric veins may not contain thrombus. These patients have poor venous collateralization and are more likely to have peritoneal signs on examination indicating bowel infarction. Acute MVT is often first recognized intraoperatively. A clear majority of patients with acute MVT will require an operation and probable bowel resection. Acute MVT has been more often associated with a thrombophilic complication than the chronic form.

Patients with chronic MVT often have symptoms lasting weeks, have involvement of larger vessels (focal thrombus at the portomesenteric confluence or splenic vein), and are usually diagnosed with a CT scan (MRI/MRA or possibly a duplex scan) identifying the large-vessel thrombosis as well as collateral circulation. When compared to acute MVT, these patients are more likely to have thrombosis related to a postoperative complication or cirrhosis. These patients rarely need an operation and almost never require a bowel resection. The Mayo Clinic experience suggests that patients with acute MVT fare worse than patients with chronic MVT. Mortality in acute MVT is higher at both 30 days (approximately 30% vs. 6%) and 3 years (64% vs. 17%).

Surgical Approach

Patients with suspected MVT and peritonitis should go to the operating room. Intra-operatively, the surgeon may find bloody ascites, and dusky, thick, and rubbery-appearing intestine. All patients should be anticoagulated as soon as possible once the diagnosis of MVT is made, preoperatively or even intraoperatively. If necrotic bowel is identified, resection should be performed. The surgeon should strongly consider a second-look laparotomy scheduled for 24 to 48 hours to reevaluate areas of questionable bowel viability. Additional bowel resections at second-look procedures are common (Table 1).

Very rarely, a large-vessel venous thrombectomy or local thrombolysis may be indicated. There are many reports in the literature using endovascular techniques. These can include mechanical thrombectomy, suction thrombectomy, and catheter-directed thrombolysis. These options should be reserved for patients who do not respond to other therapies. It is not surprising that such treatment is often futile, because the patients most likely to need surgery are those with small vessel involvement.

Patients diagnosed with MVT, but without peritonitis, should be admitted to the hospital for fluid resuscitation and systemic anticoagulation. This is most often with intravenous heparin. These patients should be closely observed for the development of peritoneal signs, which should then prompt exploratory laparotomy. There is no benefit to surgery without signs of peritonitis. Again, there are some reports in the literature regarding the use of endovascular techniques in these patients as well. These small studies discuss possible quicker recovery and decreased length of stay; however, there is no long-term benefit proven at this time.

Complications associated with MVT include bowel necrosis, portal hypertension, variceal bleeding, and recurrent thrombosis. Indefinite (i.e., lifelong) anticoagulation is often recommended because patients so treated have a lower recurrence rate and better survival. However, if the cause of the MVT is clearly identified and temporary, it may be reasonable to discontinue the anticoagulation after 3 to 6 months. Individualized therapy is advised. The patient in this scenario was anticoagulated indefinitely because of the idiopathic nature of his MVT; it is presumed that he has a hypercoagulable state even though it is undefined.

TABLE 1. Patients with Peritoneal Signs and Mesenteric Venous Thrombosis