Women and Percutaneous Interventions

Jennifer A. Tremmel MD, MS

Alexandra J. Lansky MD

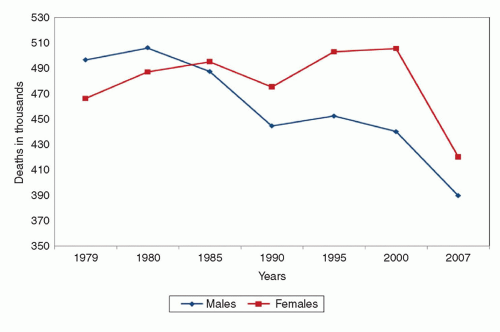

PHYSICIAN AWARENESS AND REFERRAL

Less than one in five physicians are aware that more women than men die of CVD each year, and while 80% of cardiologists and 60% of primary care physicians are aware of the American Heart Association (AHA) Evidence-Based Guidelines for Women, only about 40% of those who are aware incorporate the guidelines into their practice (2). Physicians are more likely to assign women with CVD to a lower-risk category than men even when they have a similar calculated risk. Because physician recommendations are driven by risk level assignment, this can have an effect on subsequent clinical management. Indeed, women are less likely to be referred for appropriate noninvasive and invasive diagnostic testing, experience greater delays to treatment, and are less likely to receive optimal secondary preventive medication even in the presence of confirmed coronary disease (3, 4 and 5). There are several other possible reasons for the lower referral rates and procedural delays in women, including (a) women’s older age and increased comorbidities at presentation predisposing toward conservative management, (b) variations in symptoms making diagnosis more difficult, and (c) the overall lower likelihood of obstructive coronary disease in women, leading to uncertainty regarding the risk/benefit ratio of testing and treatment.

REPRESENTATION OF WOMEN IN RESEARCH STUDIES

Cardiovascular research has traditionally been dominated by the enrollment of male subjects, with women being consistently underrepresented in published trial literature relative to their disease prevalence (6). However, an increasing awareness of sex/gender disparities throughout medical care, including differences in clinical presentation, safety and accuracy of diagnostic testing, treatment responses, and outcomes, has led to rising concerns about the ramifications of applying primarily male-based study results to the medical care of both women and men (Table 32-1) (7). A lack of data also impacts the development of evidence-based guidelines and therapies. An analysis of all randomized clinical trials used to support the AHA 2007 update of the guidelines for CVD prevention in women revealed that these guidelines were formulated on the basis of trial data in which female representation was only 30% overall (8). In addition, sex-specific reporting of results in the main trial publications was available in only about one-third of the studies, and 20 of the studies used in creating the guidelines were men-only trials.

SYMPTOMS

Although it is commonly said that women’s symptoms of myocardial ischemia differ from men’s, the differences can be subtle, though important. Failing to understand a woman’s symptom presentation can lead to unnecessary delays in diagnosis and treatment. Chest pain is the most common symptom in both women

and men, but men report it more often, and in women, it may not be the most severe, or the most prominent symptom. In addition to chest discomfort, women tend to report several other symptoms, which may include more classic associated symptoms, such as shortness of breath, nausea, and vomiting, but may also include several less classic associated symptoms, such as fatigue, dizziness, and palpitations. In general, women report a greater number of less common symptoms, with women being significantly more likely than men to report >4 symptoms.

and men, but men report it more often, and in women, it may not be the most severe, or the most prominent symptom. In addition to chest discomfort, women tend to report several other symptoms, which may include more classic associated symptoms, such as shortness of breath, nausea, and vomiting, but may also include several less classic associated symptoms, such as fatigue, dizziness, and palpitations. In general, women report a greater number of less common symptoms, with women being significantly more likely than men to report >4 symptoms.

TABLE 32-1 Differentiating Sex and Gender | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Women may get their symptoms with physical exertion, but may also experience their symptoms at rest, during sleep, and with emotional stress. Likewise, women who are premenstrual may have an increased frequency of symptoms around the time of their menstrual period. This may be because of worsening endothelial function with lower estrogen levels. While we traditionally call such symptoms “atypical,” they are quite typical among women, and the word “atypical” should be used cautiously since it is often erroneously associated with “noncardiac.”

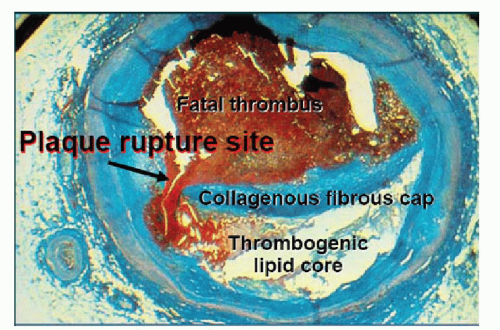

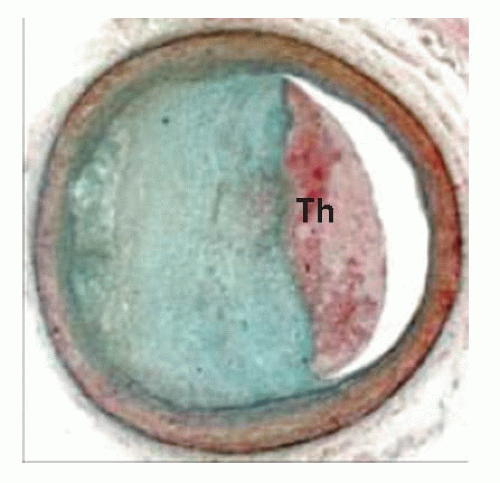

PLAQUE MORPHOLOGY

The majority of sudden coronary deaths occur in men (1). However, this sex difference decreases with advancing age, and data show that plaque morphology in fatal myocardial infarction (MI) and sudden death varies between the sexes, as well as by age (9). While most coronary thrombosis is caused by plaque rupture (˜60% of cases), ˜40% of cases are because of plaque erosion (Figs. 32-2 and 32-3). The precursor lesion of a ruptured plaque is the thin cap fibroatheroma (TCFA), which is a plaque that has a lipid-rich core covered by a thin fibrous cap. On the other hand, eroded plaques are rich in smooth muscle cells and proteoglycans, and have no apparent injury except for a denuded endothelial lining. Plaque erosions tend to be associated with less stenosis and calcification than plaque ruptures, but more mature thrombi and increased distal embolization.

FIGURE 32-3 Plaque erosion. Erosions occur over lesions rich in smooth muscle cells and proteoglycans. Luminal thrombi overlie areas lacking surface endothelium. Th, thrombus. |

Among subjects with sudden coronary death, plaque erosion is more common in women, particularly in young female smokers, while plaque rupture is more common in men and older patients of both sexes (10). Similar plaque findings have been demonstrated with IVUS in patients presenting with angina, with men having more extensive, stenotic, and calcified lesions, as well as more TCFA, than women, until after age 65 years, when significant sex differences in plaque morphology are no longer seen. However, the presence of TCFA in women with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) appears to carry a greater than twofold higher vulnerability index compared with that observed in men (11). This may, in part, help reconcile the paradox linking similar cardiovascular event rates for women and men in the context of significantly less extensive CAD in women.

VASCULAR FUNCTION

It is increasingly clear that ischemic heart disease encompasses a wider range of coronary abnormalities than anatomic blockages, and that not all anatomic blockages are atherosclerotic in nature (i.e., coronary vasospasm and coronary dissection). Much of this we have learned by studying women.

The Women’s Ischemic Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study was a landmark study that established the prognostic importance of coronary endothelial dysfunction and microvascular disease among women with angina and angiographically normal coronaries. Sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the WISE study was a four-center project that enrolled ˜1,000 women (mean age 59 ± 12 years) presenting with suspected ischemia and undergoing elective coronary angiography. Of those, 163 underwent vascular function testing with quantitative coronary angiography and intracoronary Doppler flow before and after intracoronary administration of acetylcholine, adenosine, and nitroglycerin, and were then followed up for clinical outcomes. More than half these women were found to have endothelial dysfunction, based on a paradoxical vasoconstriction in response to intracoronary acetylcholine, and endothelial dysfunction was found to be an independent predictor of adverse outcomes, including MI, heart failure, stroke, and cardiovascular death, regardless of

CAD severity (12). In addition, an evaluation of 48 WISE women found that 60% had evidence of microvascular dysfunction on the basis of an abnormal coronary flow velocity in response to intracoronary adenosine (13). The WISE investigators went on to show a significant association between coronary flow reserve (CFR) with adenosine (an indirect measure of endothelial-independent microvascular function in nonobstructed coronary arteries) and major adverse outcomes, including hospital stay for heart failure, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and death (14).

CAD severity (12). In addition, an evaluation of 48 WISE women found that 60% had evidence of microvascular dysfunction on the basis of an abnormal coronary flow velocity in response to intracoronary adenosine (13). The WISE investigators went on to show a significant association between coronary flow reserve (CFR) with adenosine (an indirect measure of endothelial-independent microvascular function in nonobstructed coronary arteries) and major adverse outcomes, including hospital stay for heart failure, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and death (14).

The WISE study also showed that women with symptoms and signs suggestive of ischemia but without obstructive CAD are at an increased risk for cardiovascular events compared with asymptomatic community-based women. The 5-year annualized rates for cardiovascular events were 16.0% in WISE women with nonobstructive CAD (stenosis in any coronary artery of 1%-49%), 7.9% in WISE women with normal coronary arteries (stenosis of 0% in all coronary arteries), and 2.4% in asymptomatic community-based women (p ≤ 0.002), after adjusting for baseline CAD risk factors (15). In another analysis, a comparison of WISE women with nonobstructive versus obstructive disease showed that at 5-year followup, nearly half of women with nonobstructive disease reported functional disability (16). They also had a similar frequency of typical angina compared with women with obstructive disease. After 1 year, repeat angiography or angina hospitalization was 1.8-fold higher in women with nonobstructive CAD compared with those with one-vessel CAD (p < 0.0001), and during the 5-year followup, 20% of women with nonobstructive disease were hospitalized for angina. Overall, for women with nonobstructive CAD, the average estimated lifetime cost related to the burden of continuing symptoms and drug treatments is $767,288. Thus, among patients with angina, absence of angiographic evidence of CAD is far from sufficient to establish a patient’s diagnosis, risk, or outcome.

While the WISE study looked at women with relatively stable angina, women with angiographically nonobstructed coronary arteries can also present with MI. Several mechanisms have been implicated, including transient thrombosis with endogenous thrombolysis, distal embolization of microatherothrombotic debris, coronary vasospasm, plaque disruption (rupture or ulceration) that does not lead to luminal occlusion, and takotsubo cardiomyopathy (17). All of these may occur in men as well, although several appear to have a female preponderance. In addition, coronary dissection should be mentioned, as it often presents as a small caliber but nonobstructed vessel, and when it does occur with obstruction, it can be mistaken for an atherosclerotic lesion if there is not a high index of suspicion. Coronary dissection is more common in women than in men, and should be strongly suspected in young women without significant cardiac risk factors, particularly those who are peripartum or taking oral contraceptives. Lately, coronary dissection has also been described in young women with coronary fibromuscular dysplasia (18).

PCI AND DES IN WOMEN

Across the spectrum of patients presenting for PCI, from stable angina to ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), there are consistent baseline clinical and angiographic differences seen between women and men. Women are older, and have more comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, and renal insufficiency, but less prior tobacco use. Women are also less likely to have had a prior MI, PCI, or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) than men. However, women are more likely than men to have had prior congestive heart failure and present in a higher Killip class, yet with a more preserved left ventricular systolic function. In addition to being less likely to have obstructive disease, when they do have disease, it is generally less high risk and less multivessel (19). Because of these multiple differences, adjusting for age, comorbid clinical conditions, and CAD severity is a necessary part of sex-based research, and most studies find that after adjusting for these factors, differences between the sexes is lessened, or even eliminated. While this can demonstrate that a difference is not based on sex, per se, it does not negate the consistent baseline differences that still need to be taken into account in the care and management of both female and male patients.

The NHLBI Dynamic registry, which collects data on consecutive patients undergoing PCI at multiple sites in the United States, revealed that women undergoing PCI in the mid-1980s had a significantly increased risk of in-hospital mortality compared with men (adjusted OR 4.53, 95% CI 1.39-14.7). By the late 1990s, this sex difference in mortality had disappeared (adjusted OR: 1.60, 95% CI: 0.76-3.35), although it continues to persist for higher risk women, particularly those presenting with STEMI (20). In a more recent analysis of the Dynamic registry, which was the first to include drug-eluting stents (DES), women and men continued to have similar outcomes, including similar stent thrombosis rates, MI, and death, both in-hospital and at one year (21).

In general, women and men have had similar benefits from stents in reducing restenosis and revascularization, and both have shown added benefit with DES compared with bare-metal stents (BMS). In a retrospective cohort study of 4,936 consecutive patients (28.2% women) who underwent PCI between 2000 and 2004 (before and after the introduction of DES) women and men had no difference in risk of all-cause death, MI, or target vessel revascularization (TVR) at 3 years, and women treated with DES were significantly less likely to have TVR and major adverse cardiac events (MACE) compared with women treated with BMS (adjusted HR for TVR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.36-0.75 and adjusted HR for MACE: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.48-0.83) (22).

Such findings have continued with newer-generation DES as well. In a sex-based analysis of 2,132 patients (28.5% women) receiving zotarolimus-eluting stents (ZES), women and men had similar rates of MI and death at 2 years, and women actually had lower rates of TVR (8.2% vs. 10.4%; p = 0.005) and target vessel failure (TVF) (9.9% vs. 12.8%; p = 0.004) compared with men (23). An IVUS analysis of neointimal hyperplasia in women compared with men receiving ZES reiterated this clinical finding, showing that female sex was independently associated with decreased neointimal hyperplasia in patients treated with ZES (24). Studies comparing women and men treated with everolimus-eluting stents (EES) versus PES have demonstrated that both women and men receiving EES have lower MACE rates than those receiving PES, and specifically, women with EES continue to have lower MACE rates than those with PES at 3 years (12.2% vs. 22.6%; p = 0.03), as well as lower TVF (16.0% vs. 26.4%; p = 0.03) (25, 26). None of the DES studies have shown a sex difference in stent thrombosis rates.

MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

There has been a long-standing dilemma on how best to manage women presenting with ACS (defined as unstable angina or non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction [NSTEMI]). The benefits of an invasive strategy compared with a conservative or “selective invasive” strategy have been consistently demonstrated in men, but results in women have been conflicting.

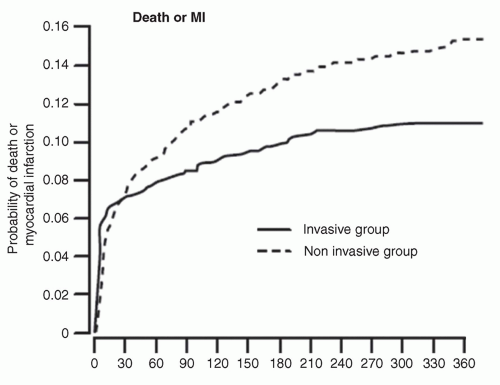

FIGURE 32-4 There was an overall benefit of the invasive strategy over the conservative strategy in FRISC II. |

The FRISC II trial (n = 2,457, 30% women) found that an early invasive strategy (catheterization within 7 days) resulted in a composite reduction of death and MI (RR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.60-0.92) compared with a conservative strategy (Fig. 32-4). However, further analysis revealed that this benefit applied only to men (27). Specifically, men treated invasively experienced a lower rate of death and MI at 1 year (9.6% vs. 15.8%; p < 0.001), whereas there was no difference in women’s outcomes between the invasive and conservative groups (12.4% vs. 10.5%; p = NS), and in fact, women showed a trend toward harm with the invasive strategy (p = 0.008 for sex interaction) (Fig. 32-5). This apparent sex difference was further explored, and seemed to persist, even when controlling for confounding factors, such as age, comorbidities, and severity of CAD.

A subanalysis of the RITA 3 trial (n = 1,810, 38% women) reported similar results (28). For the primary outcome of death or nonfatal MI at 1 year, the adjusted OR for men (invasive vs. conservative) was 0.63 (95% CI 0.41-0.98) and for women, 1.79 (95% CI: 0.95-3.35; p = 0.007 for sex interaction). There was also an indication of differences in death and MI between women and men over the longer term, with an adjusted HR for men of 0.61 (95% CI: 0.44-0.85) and for women, 1.09 (95% CI: 0.70-1.71; p = 0.042 for sex interaction).

In TACTICS-TIMI 18 (n = 2,220, 34% women), women had a 28% odds reduction in the primary end point (death, MI, or rehospitalization at 6 months) with an early invasive strategy (catheterization within 48 hours) (adjusted OR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.47-1.11), which was considered similar to the benefit in men (adjusted OR: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.47-0.88; p = 0.60 for sex interaction) (29). While there was a trend toward an improved outcome in women with higher TIMI risk scores and ST-segment changes who received the invasive strategy, this was not statistically significant. On the other hand, women with elevated levels of troponin T had a marked benefit with the invasive strategy, and when adjusted for baseline characteristics, the benefit of invasive therapy in women with elevated troponin T levels was further enhanced (adjusted OR: 0.47, 95% CI: 0.26-0.83).

A meta-analysis published in 2008, which included all relevant randomized clinical trials, confirmed that in ACS, an invasive strategy has a comparable benefit in men and high-risk women for reducing the composite endpoint of death, MI, or rehospitalization with ACS, but that in low-risk women, a conservative strategy should be favored (30). From the findings of these studies, it is currently recommended that women with ACS should undergo an invasive strategy if they have high-risk features (particularly elevated cardiac biomarkers), but if they have low-risk features, a selective invasive strategy should be pursued. Regardless of the strategy, women should be managed with the same pharmacological therapy as men, both in the hospital and for secondary prevention.

TREATMENT OF ACUTE MI IN WOMEN

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree