■ Primary vascular tumors are exceedingly rare, frequently mimic other oncologic disease processes, and may evolve slowly—leading to delay in diagnosis and treatment. Although most commonly arising from large vessels such as the aorta and vena cava, primary vascular tumors may also originate from distal branches of the iliac, mesenteric, and renal arteries. Classification systems (Wright/Salm classification) have broadly categorized primary vascular tumors as intimal (majority, 70%) and mural.3

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ Patients with complex intraabdominal oncologic pathology are best managed by a multidisciplinary care team at a tertiary care center. If tumor extension to adjacent vascular structures is suspected, surgical planning should include evaluation of potential revascularization options by a vascular surgeon.

■ The initial assessment should include a thorough evaluation of the patient’s presenting symptoms. This may include focal or regional abdominal pain resulting in tumor parenchyma pressing against adjacent structures. Patients may also present with gastrointestinal symptoms such as early satiety, nausea, and vomiting. Erosive gastrointestinal lesions may manifest with hematochezia, melena, or hematemesis. Constitutional flu-like symptoms, fevers, malaise, fatigue, night sweats, and muscle aches may also rarely present in patients with certain patients with rapidly expanding tumors.

■ Depending on the primary site and tissue of origin, tumor-associated physical findings may not be obvious until relatively late in the disease process. Abdominal distension can result from increasing tumor volume or from serous ascites due to portal venous compression. Tumor mass effect or infiltration of the inferior vena cava (IVC) or iliac venous system may lead to unilateral or bilateral lower extremity edema, dilated abdominal wall veins, evidence of deep venous thrombosis (DVT), biliary symptoms, and renal insufficiency. Accordingly, physical examination should not only include a thorough abdominal exam with palpation of all nodal basins but also a complete vascular exam with evaluation of limb pulses, Doppler signals, and assessment of extent/grade of limb edema.

■ Patient with primary vascular tumors, particularly ones with intimal expansion and growth, can present with evidence of venous or arterial embolization. Manifestations of recurrent venous pulmonary emboli include shortness of breath, respiratory distress, and hemodynamic changes including tachycardia and right heart failure. Depending on the volume of arterial emboli, symptoms can range from lower extremity pain to digital discoloration.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ Tumor staging and classification systems are beyond the scope of this chapter. Please refer to other excellent references for tumor-specific staging modalities and requirements.2,4

■ Patients deemed candidates for surgical resection by a multidisciplinary team should receive a high-resolution, thin-slice (at least 1 mm), multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) scan with intravenous contrast injection to allow for imaging during arterial and venous phases. Image acquisition should allow for multiplanar sagittal, coronal, and three-dimensional reconstructions. This type of detailed imaging provides valuable information regarding tumor margins, suspected histologic subtype, and grade and can also help determine the morphology, patency, and extent of involvement of adjacent vascular structures.

■ In situations where mesenteric venous thrombosis is visualized on MDCT, specific postprocessing protocols may be further implemented to improve clarity regarding the extent of thrombus burden and associated and/or resultant venous congestion.

■ Adjunct imaging studies may also include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasonography, and rarely, angiography/venography. Particularly, in patients with concern for osseous or neurogenic tumor involvement, MRI may be particularly useful in defining tissue planes and tumor parenchyma boundaries. MRI also has a nearly 100% sensitivity for detecting intracaval tumor thrombus.

■ Autogenous vascular conduit may be necessary for adequate revascularization, particularly following bowel resection and reconstruction. When anticipated, preoperative venous duplex scanning of the lower extremities will help document the presence and usage of superficial femoral vein as potential graft conduit. The presence of deep venous obstruction, either acute or chronic, may preclude venous harvest from that particular extremity. Similarly, the bilateral lower extremity greater saphenous veins should be evaluated for patency, diameter, and adequate length.

■ Occasionally, preoperative or intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography may be needed to confirm the proximal extent of intracaval tumor thrombus visualized using other cross-sectional imaging modalities and determine whether the tumor thrombus is encroaching into the right atrium.5

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Patient Selection

■ Whenever possible, the goal of surgical extirpation of abdominal solid organ tumors should be oncologic cure. This assumption presupposes tumor localization to a distinct anatomic region that will allow for resection with negative macroscopic and microscopic margins. Thus, the goals of the procedure should be clearly defined by sufficient preoperative high-quality anatomic cross-sectional imaging, multidisciplinary consultation, and discussions with the patient regarding the operative risks, benefits, expectant outcomes, and overall prognosis.2,6

■ Abdominal solid organ tumors are traditionally considered unresectable when they involve the arterial or venous vasculature, are diffusely metastatic throughout the peritoneum or at remote sites, or involve the root of the mesentery or spinal cord to a significant extent. Patients with extensive tumor burden precluding resection may still be offered incomplete removal or debulking operations to potentially prolong survival and improve symptom palliation.6

■ Equally as important as the anatomic considerations, preoperative patient functional status is a significant determinant of surgical eligibility. Performance assessments, such as outlined by the Karnofsky or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score, help predict patient-specific postoperative quality of life.2,7 At our institution, patients who are bedridden at the time of initial assessment, severely disabled, or unable to independently perform activities of self-care are often not offered curative resection.

■ Candidacy for intraabdominal vascular reconstruction is also contingent on the extent of potential or preexisting vascular compromise. As such, we have typically attempted arterial reconstruction when tumors involve critical arterial structures such as the aorta, celiac artery and its branches, proximal superior mesenteric artery (SMA), common/external iliac artery, and the internal iliac artery in the setting of an embolized, occluded, or resected contralateral internal iliac artery. Similarly, venous reconstruction is also anticipated when tumors margins appear to include the vena cava, portal, superior mesenteric, common, and external iliac veins.

Preoperative Planning

■ Items to consider in preoperative multidisciplinary review include the extent of planned gross surgical resection margins, the need for preoperative arterial or venous embolization, the need for other prophylactic procedures such as placement of ureteral stents or nephrostomy tubes, and the likelihood for intestinal resection and/or reconstruction.

■ Ureteral stent placement should be considered in all patients who demonstrate evidence of ureteral obstruction, renal hydronephrosis, or urinary obstructive signs or symptoms from either tumor mass effect or invasion of urologic structures. Moreover, ureteral stents should also be considered in patients with pelvic tumors where there is potential concern of ureteral injury during resection of the tumor or during vascular reconstruction.

■ A thorough review of detailed preoperative imaging will greatly facilitate proper conduit selection and preparation and, ultimately, a successful outcome. Particular attention should be directed to the length of vascular segment involved by adjacent tumor, the branch points and bifurcations present along this length, and which segments, if any, are circumferentially encased by tumor parenchyma.

■ Attention should be paid as to whether planned resection will include vessels which are already occluded with adequate collateral circulation already in place, or whether adjacent or contralateral vascular structures are capable of supplying adequate inflow and outflow. Vascular segments to be reconstructed should be patent and preserved to the greatest extent possible during the planned tumor resection.

■ Endovascular embolization is the preferred method of preoperative vascular occlusion prior to open surgical resection. This strategy is commonly used for preoperative splenic artery/vein embolization prior to planned surgical splenectomy, internal iliac artery embolization prior to planned pelvic tumor resection, and renal artery/vein embolization prior to planned nephrectomy with or without the need for further exposure of the retrohepatic IVC. For this purpose, the preferred size of coils/plugs is estimated based on the diameter and length measurements of the target vessel on preoperative cross-sectional imaging and is typically oversized by up to 20% of the target vessel diameter. For additional details regarding visceral embolization techniques, refer to Chapter 19 (Stenting, Endografting, and Embolization Techniques: Celiac, Mesenteric, Splenic, Hepatic, and Renal Artery Disease Management). For additional details regarding internal iliac artery embolization techniques, refer to Chapter 24 (Advanced Aneurysm Management Techniques: Management of Internal Iliac Aneurysm Disease).

■ Aortoiliac arterial involvement often requires resection followed by reconstruction with patch angioplasty, interposition, or extraanatomic bypass. Type of reconstruction and conduit type (autogenous venous allograft, cryopreserved homograft, or synthetic conduit) is contingent on the type of tumor, extent of vascular segment involvement, and degree to which intestinal reconstruction is also anticipated. In the latter case, when contamination by succus entericus is likely, autogenous femoral vein conduits for iliac artery reconstructions and IVC or spliced femoral vein conduits for aortic reconstructions are preferred. Alternatively, when not available, rifampin-soaked, gel-sealed knitted Dacron conduit may serve as a potential substitute with acceptable results.8

■ Reconstruction of the celiac trunk, common hepatic artery, SMA, portal vein, and superior mesenteric vein (SMV) are similarly contingent on the extent of involvement of these structures with tumor pathology. Unless the artery in question is circumferentially involved, it is our preference to resect only the portion of vessel wall directly involved with tumor while preserving the remaining vessel architecture with patch repair. Autogenous venous conduit (using superficial femoral vein or greater saphenous vein or femoral vein) is preferred for vessel segments requiring interposition grafting.

■ The mainstay of treatment of primary and secondary tumors of the IVC is surgical resection and reconstruction. The extent of reconstruction is contingent on the type of tumor, extent of caval involvement, and the anatomic segments involved. Adequate retrohepatic caval exposure is challenging and may require total vascular isolation of the liver to minimize blood loss during this maneuver. In circumstances where the IVC is chronically occluded with tolerable lower extremity edema and adequate renal function, ligation and resection without reconstruction should be considered. On the other hand, patients with recent occlusion of the IVC, few venous collaterals, notable lower extremity symptoms, or renal insufficiency should be considered for either interposition grafting or patch venoplasty.

Operating Room Setup

■ Preoperative endovascular embolization procedures should be performed in an angiography suite or hybrid operating room, equipped with a fixed-imaging apparatus, floating-point carbon fiber operating table, fluoroscopy platform, and monitor-viewing bank. A full complement of compatible guidewires, catheters, sheaths, coils, and plugs should also be available.

■ Open tumor operative resection procedures are best performed in an operating room setting with adequate space to facilitate the maneuvering of multiple surgical subspecialty teams and their necessary operative trays/equipment.

■ Most intraabdominal operative tumor resection and reconstruction procedures may be performed with the patient in the supine position. In the surgical field, the patient’s lower extremities should be prepared for vein harvest if potentially necessary.

■ In patients who require retrohepatic IVC exposure and reconstruction, the left lateral decubitus position should be employed to facilitate right thoracoabdominal exposure through the 8th or 9th rib interspace.

■ Placement of ureteral stents will require initial positioning of the patient in lithotomy position and then subsequent repositioning of the patient to facilitate further planned surgical intervention.

TECHNIQUES

AORTIC RECONSTRUCTION

■ For a discussion of the technical exposure of the paravisceral, pararenal, and infrarenal aorta, please refer to Chapters 14 (Exposure and Open Surgical Management at the Diaphragm), 15 (Retroperitoneal Aortic Exposure), and 22 (Advanced Aneurysm Management Techniques: Open Surgical Anatomy Repair).

First Step

■ The surgical exposure of an intraabdominal tumor either directly adjacent or involving the aorta should aim to not only provide adequate exposure of tumor resection but also facilitate adequate proximal and distal arterial control. A traditional midline abdominal incision, extending from the xiphoid process to the pubis, can facilitate this in the majority of patients.

■ In patients with wide costal margins or an anticipated need for wide parahepatic or parasplenic exposure, a bilateral subcostal incision (also known as Michigan smile) may also be useful.

■ For large abdominal tumors, renal tumors, or tumors with cephalad intraabdominal extension to the level of the diaphragm, a lateral decubitus thoracoabdominal approach to facilitate both adequate tumor exposure as well as vascular proximal control and reconstruction is advised.

Second Step

■ Proximal aortic control can often be obtained directly above the anticipated cephalad margin of the tumor. In this circumstance, via either retroperitoneal or transperitoneal approaches, the medial and lateral aortic margins are cleared for a distance of 2 to 3 cm proximal to the tumor margin. The exposed segment is inspected for lumbar vessel branches, which may be externally ligated as necessary to aid in exposure and control. A large, slightly curved vascular aortic clamp (e.g., DeBakey aortic occlusion clamp) is best suited to obtain proximal aortic control.

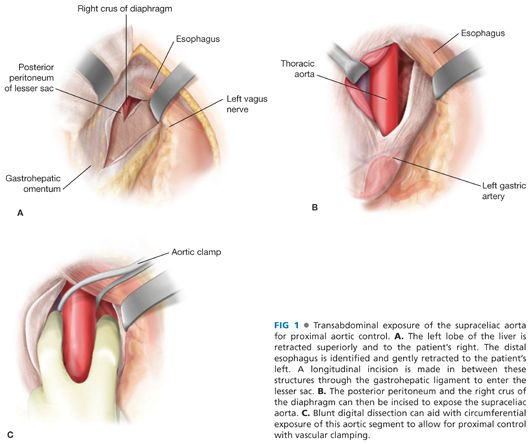

■ Supraceliac or suprarenal aortic exposure may be necessary for optimal control (FIG 1).

■ For control of the supraceliac aorta, the peritoneal cavity is entered below the level of the xiphoid process. With cephalad retraction of the left lobe of the liver, the left triangular ligament of the liver is divided and the lesser sac is entered via a longitudinal incision in the gastrohepatic ligament. Care should be taken here to avoid injury to the esophagus (identified by aid of orogastric/nasogastric tube placement) or a replaced left hepatic artery. For additional exposure, the median arcuate ligament and the right crus may be divided (FIG 1).

■ Suprarenal aortic control is obtained following circumferential dissection and mobilization of the left renal vein off the ventral surface of the aorta. Left renal vein inferior lumbar branches should be ligated to facilitate mobilization. In rare circumstances, the left renal vein may need to be ligated during this maneuver. When this is anticipated, existing collateral veins such as the left gonadal, adrenal, or lumbar should be intentionally preserved prior to division of the left renal vein.

■ Infrarenal aortic exposure can be achieved either via transperitoneal or retroperitoneal approaches. If the tumor has pelvic extensions or if exposure/control of the right iliac system is anticipated, a transperitoneal approach may be preferable.

Third Step

■ Depending on the extent of aortic tumor involvement, durable repair may be achieved using either patch angioplasty or interposition grafting.

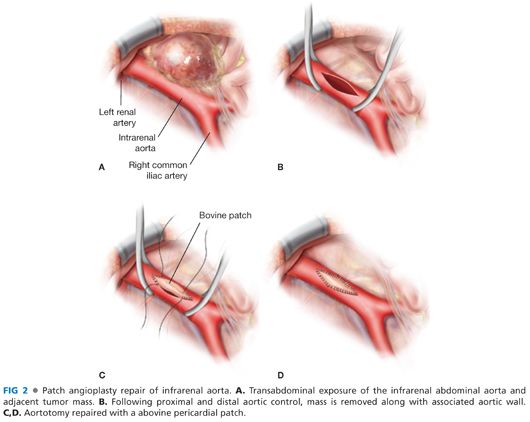

■ Patch repair is commonly performed with a woven Dacron, bovine pericardium, or autogenous femoral vein. The patch is fashioned in a manner to facilitate a wide repair without narrowing the residual the aortic lumen. The anastomosis is usually performed with 4-0 Prolene sutures, in a running fashion, with one suture starting from each end of the patch repair. Depending on the age of the patient, presence and extent of retroperitoneal soilage by intestinal contents, and amount of retroperitoneal inflammation present, polyester pledgets may be required to minimize suture-related aortic injury and needle hole bleeding (FIG 2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree