Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery for Wedge Resection, Lobectomy, and Pneumonectomy

Ali Mahtabifard

Robert J. McKenna Jr.

Video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) is an appealing alternative to thoracotomy for many types of pulmonary resections. The success of laparoscopy in the 1980s, improved endoscopic video systems, and development of endoscopic staplers led thoracic surgeons to apply this technology to the chest cavity. Since the first VATS lobectomy (VL) with anatomic hilar dissection performed in 1992, a variety of authors from around the world have published series that report the safety and advantages for this approach.6,9,18,30 The expectation for minimally invasive thoracic procedures has been that they would reduce morbidity, mortality, and hospital stay and allow quicker return to regular activities for patients after procedures that formerly required major incisions. The recent literature suggests that VATS lobectomy meets these expectations.16,22,31

Although there is no large, randomized prospective study, the worldwide experience with VATS lobectomy for pulmonary resection is now sufficiently large enough to compare VATS with open thoracotomy for pulmonary resection. The literature shows that, in the hands of experienced VATS surgeons, a lobectomy is a safe operation that offers patients comparable or better complication rates, compared to lobectomy by thoracotomy (Table 35-1). The momentum to perform minimally invasive pulmonary resections is really growing in the field of general thoracic surgery. This chapter will detail the techniques for performing VATS resections and compare the outcomes for VATS and open procedures.

Definition

The exact definition of a VATS lobectomy (VL) is controversial. The controversies center around the issues of rib spreading, instrumentation, and anatomic dissection. Basically, a VL should include the following: a true anatomic dissection with nodal sampling or dissection, an incision <10 cm long with no rib spreading, and visualization on a monitor rather than through the incision. The soft tissue can be held open by a Weitlander retractor so that suctioning in the pleural space does not expand the lung. Some surgeons use standard open instruments, while others use disposable, minimally invasive instruments; however, this should not be part of the definition. An absolute requirement is that a VL should be a standard anatomic dissection. While simultaneous ligation of the hilar structures has been reported,11 it is to be discouraged. Some thoracic surgeons perform “hybrid” operations that involve some rib spreading through incisions that are smaller than the usual thoracotomy incisions. This approach is not addressed in this chapter because there are no data to compare the hybrid operation and a true VATS lobectomy.

The techniques for lung resection—wedge, lobectomy, and pneumonectomy—with video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) are now well established. This chapter presents details about the current approaches and results.

Vats Resection of Lung Nodules

The emergence of VATS has changed the algorithm for the diagnosis of a lung nodule. Needle biopsies are performed less often. Currently, because the morbidity and mortality of a wedge resection is so low, there is a lower threshold to perform a VATS biopsy of a suspicious lung mass. VATS is the most common and simplest method for lung biopsy.

Localization of Lung Nodules by VATS

Resection of a lung mass begins with identification of the mass. Because the small incisions used for VATS make palpation of the lung more challenging than through a thoracotomy, a key to successful resection of a lung mass via VATS is the ability to find the lesion. Therefore accurate localization of a lung mass requires an excellent understanding of the correlation between computed tomography (CT) images and lung anatomy to identify the target area of the lung. An experienced thoracic surgeon can almost always find a lung mass in this fashion. The lung is quite mobile, so most areas of the lung can be brought to a finger placed through the incision in the fourth intercostal space in

the midaxillary line. Other thoracic surgeons are facile at “feeling” the lung with an instrument that basically acts as a finger extension.

the midaxillary line. Other thoracic surgeons are facile at “feeling” the lung with an instrument that basically acts as a finger extension.

Table 35-1 Results of Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery (VATS) Anatomic Pulmonary Resections | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There are techniques to assist with intraoperative identification of a small mass that cannot be palpated.5,13,28 Indications for these techniques include ground-glass opacities <1 cm, small masses <5 mm, and masses >2 cm below the pleural surface. In some cases, the small ground-glass opacities (GGOs) have been difficult to palpate even after the lung tissue has been removed from the patient; therefore the use of a wire has helped the pathologist to prepare slides from the correct area in the lung. Under CT guidance, the radiologist places a hook wire into or adjacent to the nodule. This is the same hook wire used for localization of a breast mass. The wire should be cut flush with the chest wall. (If the wire has been taped to the chest without being cut, the wire may become dislodged from the mass if the patient develops a pneumothorax and the lung pulls away from the chest wall.) As Mack and colleagues13 noted, this technique is associated with minimal complications (e.g., rare dislodgment of the wire or pneumothorax). Wire localization was used more often in the early days of VATS, before surgeons realized that it was rarely necessary. This technique has again become more common, because screening CT scans identify small nodules that may be difficult to locate with VATS.

Daniels and associates5 have described a technique using transthoracic percutaneous radiotracer injection with VATS radioprobe localization and excision of small pulmonary nodules. Using this technique, a CT-guided injection of radiotracer solution is made into or adjacent to the nodule on the day of surgery. Next, an intraoperative gamma probe is used to localize the lesion, followed by VATS excision of the lesion.5

Wedge Resection

Under one-lung general anesthesia, the patient is placed in a lateral decubitus position with a slight posterior tilt. A double-lumen tube allows better decompression of the lung to be biopsied than a single-lumen tube with a bronchial blocker. The bed is flexed to help get the hip out of the way of the trocar and thoracoscope. It may also help to open the intercostal spaces.

The incisions for a wedge resection are seen in Figure 35-1. Incision 1 is 2 cm long and is made in the sixth intercostal space in the midclavicular line. This is usually one intercostal space below the inframammary crease. The incision is made in the middle of the interspace and is tunneled posteriorly through the tissues of the chest wall, rather than perpendicular to the skin, because this avoids bleeding from smaller branches of the mammary artery and prevents instruments passing through this incision from bumping into the pericardium or the diaphragm.

Incision 2 is made for the trocar and thoracoscope in the eighth or ninth intercostal space in the midaxillary line to the posterior axillary line. The incision is made over a rib and is angled superiorly to reduce the torque on the intercostal nerve. By placing the camera through this port, the optimal panoramic view of the thoracic cavity is obtained. A 5- or 10-mm thoracoscope can be used. We prefer the 30-degree, 5-mm scope because it requires a smaller incision and places less torque on the intercostal nerve. In addition, the 30-degree scope allows the surgeon to look around structures better than the 0-degree scope.

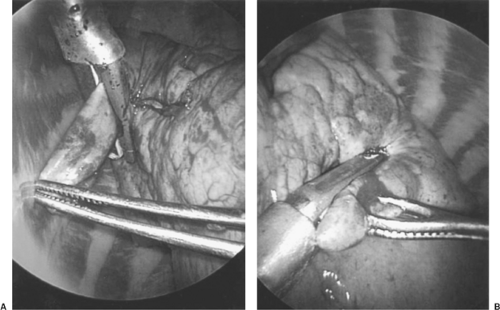

Figure 35-2. The stapler is first fired in a cephalad direction (A) and then in a posterior direction (B) to perform a wedge resection to remove a lung mass. |

Finally, incision 3, which is 2 cm long, is made in the fourth intercostal space. It extends anteriorly from the border of the lattisimus dorsi muscle. Through this incision, a finger can palpate most of the lung and a ring forceps can hold the lung for the biopsy.

Technique for Wedge Resection

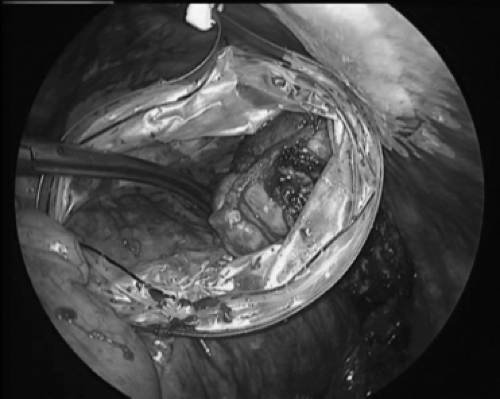

The wedge resection begins with a ring forceps through incision 3 to hold the lung. Care should be taken to not crush the mass because it may no longer be palpable after it is crushed. A ring forceps through incision 1 may compress the lung parenchyma below the mass to hold the lung for palpation and compress thicker lung parenchyma to facilitate passage of the stapler across the lung tissue. The endoscopic stapler is then passed through incision 1 (Fig. 35-2) and fired. In some cases, the stapler through incision 1 can complete the resection. In other cases, a stapler through incision 3 can complete the resection. If there is a possibility that the mass is malignant, then the specimen is placed in a standard Endocatch bag (US Surgical, Norwalk, CT) for removal (Fig. 35-3) because cancer has recurred in VATS incisions after biopsy.3 If frozen section shows that the mass is inflammatory, cultures of the specimen are sent. If the mass proves to be a lung cancer, then VATS lobectomy is performed.

Alternatively, a lung mass can be carved out with electrocautery and the lung parenchyma sutured. This requires proper exposure, traction, and countertraction. This is certainly more challenging with VATS than via an open procedure. Smoke from the electrocautery can be problematic. Suction in the thoracic cavity causes the lung to reexpand unless air can flow into the thoracic cavity through at least one of the incisions. Many thoracic surgeons find endoscopic suturing difficult, so this approach is less common than wedge resection with staples.

Postoperative Care After Wedge Resection

While there are reports of outpatient lung biopsies,2 the procedure is usually an inpatient procedure. Postoperatively, unless the patient has severe respiratory compromise, it is uncommon for the patient to go to the intensive care unit. The chest is usually drained with a single 28-Fr chest tube and the chest drainage system need not be attached to suction unless the patient develops significant subcutaneous emphysema. Postoperative pain is usually controlled with Dilaudid SQ and Vicodin PO. The patients have no dietary restrictions and are ambulated immediately. No routine labs or chest x-rays are necessary unless clinically indicated (fever, excessive chest drainage, management of diabetes, etc.). The chest tube is removed when there is no air leak and the chest tube drainage is <300 mL in 24 hours (usually on the first postoperative day). The length of stay is often 1 day for a wedge resection.

General Approach for a VATS Lobectomy

A VATS lobectomy should be the same procedure that is performed through a thoracotomy. This includes the individual ligation of vessels and bronchus for the lobectomy and a lymph node dissection or sampling.17

Most lobectomies can be performed by VATS. Importantly, the procedure should be the best operation for the patient. If the procedure can be performed with VATS, then the patient may experience some benefits. A high percentage of lobectomies can potentially be performed with VATS. In 2005, a total of 94% of the author’s 239 lobectomies were performed by VATS; however, only 18% of lobectomies in the 2005 Society of Thoracic Surgeons general thoracic surgery database were performed by VATS (personal communication). The momentum for VATS lobectomy is growing as patients demand the procedure and as thoracic surgeons gain an understanding of the techniques involved.

The indications and contraindications for the procedure (Tables 35-2 and 35-3) are similar to the indications for lobectomy via thoracotomy. Generally the tumor must be small enough for removal through the 5-cm utility incision, although we have removed an 8-cm tumor through a 5-cm incision by cutting one of the ribs at the posterior end of the utility incision. Centrally located tumors may require a thoracotomy to determine whether sleeve resection or a pneumonectomy is appropriate, although to date we have performed 13 VATS sleeve resections with good results.15 Safe dissection around the vessels and in the mediastinum after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation may require a thoracotomy. However, experienced VATS surgeons can usually perform VATS lobectomies after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and sometimes after chemotherapy and radiation treatment.23

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree