Gastroenteric Cysts and Neurenteric Cysts in Infants and Children

Alan P. Ladd

Robert J. Touloukian

Frederick J. Rescorla

Jay L. Grosfeld

Gastroenterogenous and neurenteric cysts are relatively rare mediastinal masses of infancy and childhood. They occur as a result of abnormal separation of embryonic germ cell layers with persistence of endodermal elements closely associated with or within the spinal canal. Heimburger and Battersby,17 in a 15-year review, reported only three cases in a report concerning 42 mediastinal tumors in children. Various descriptive terminologies have been used to clarify these lesions; however, for the purpose of this discussion, a thoracic neurenteric cyst is defined as a thin-walled cystic structure with an associated cervical or thoracic vertebral anomaly. The association of such cysts with abnormalities of the spinal column is well documented and can range along a spectrum from mediastinal masses with minimal spinal abnormality to lesions completely within the dura with no extraspinal components.2

Gastroenterogenous cysts of the mediastinum are gastric cysts that may or may not communicate with the gastrointestinal tract below the diaphragm. The cyst may also be associated with vertebral anomalies, although it has no intravertebral communication. It would appear that gastroenterogenous and neurenteric lesions arise from a common embryologic defect in development and are part of a spectrum of anomalies that include neurenteric cysts, gastroenteric cysts, and dorsal enteric fistulas and diastematomyelia, described by Bremer.5

Etiology

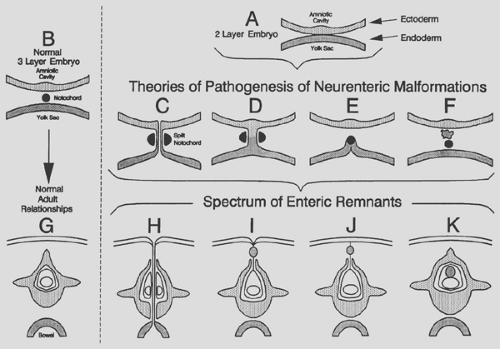

Various theories have been proposed to explain the development of enterogenous cysts. The existence of spinal abnormalities is essential in the definition of neurenteric cysts and has been reported frequently with mediastinal gastric cysts. In 1935, Stoekel40 first appreciated this relationship when he described a lesion firmly attached to the vertebrae and noted that the notochord and endoderm were at one time in intimate contact. In 1937, Guillery15 described a cystic mediastinal lesion associated with a separate cyst in the neural canal. In 1952, Veeneklaas42 suggested that these abnormalities may develop from an accident involving the spine and foregut at a time when their cells were adjacent to each other. He stated that a failure of complete separation could account for the development of cysts and diverticula of the foregut, including the stomach. From these observations and the frequent association of neurenteric cysts with vertebral deformities, a pathogenic process early in gestation has been hypothesized, with an aberrant ectoderm–endoderm adhesion.

In the third week of development, the notochord forms from the ectoderm. These specialized cells then migrate dorsally and are enveloped by the proliferating mesoderm, which later segments and forms the vertebral bodies. Fallon and associates9 postulated that the withdrawal of the notochord may bring with it a portion of the adjacent endodermal lining, thus leaving a ventral attachment on the notochord to the endoderm. From this lining of endodermal cells, various cysts and duplications could arise, lined with mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract. In addition, closure of the endodermal orifice may result in instances of foregut cysts without any alimentary tract communication. If a communication persisted, it would explain the presence of mediastinal cysts with communication to the gastrointestinal tract in the abdomen. In addition, communication with the notochord would prevent normal anterior formation of the vertebral column.

In 1954, McLetchie and associates25 proposed that a cleft occurred in the notochord along with the formation of an endodermal–ectodermal adhesion, with subsequent neural or alimentary tract anomalies or both. These researchers explained how lesions could form within the chest with or without spinal communication and with or without communication with the infradiaphragmatic gastrointestinal tract. Rhaney and Barclay36 postulated that the endoderm becomes “intercalated not merely in the notochord, but further dorsally in the neuro-ectoderm” to fully explain the unusual presence of an enterogenous cyst within the spinal cord. They suggested that this misplaced endoderm traverses a cleft in the notochord and that some of these cells become detached from the endodermal tube as the foregut moves away from the notochord.

Another theory, proposed by Bremer,5 is that the neurenteric cyst represents an incomplete obliteration of the accessory neurenteric canal of Kovalevsky. This canal is a transient communication between the amniotic cavity and yolk sac on the dorsal surface of the fetus. Persistence of this structure results in a connection between the foregut and dorsal surface of the fetus and theoretically might explain the occurrence of such lesions

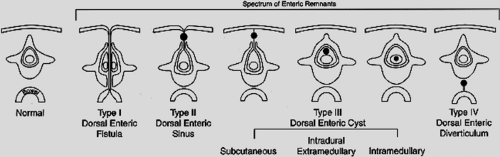

as neurenteric cysts, dorsal enteric fistulas, or split cord malformations, as in diastematomyelia. Bentley and Smith4 expanded on Bremer’s theory, proposing the splitting of the notochord may be the primary event in this process. The resulting deficiency in the overlying neural plate could allow for herniation of endodermal elements through the spinal column to the surface ectoderm. Later obliteration or persistence of portions of this neurenteric connection would then allow for a variety of clinical presentations (Figs. 203-1 and 203-2). By this theory, involution of all but the ventral portion of the connection would result in a duplication or diverticulum of the alimentary canal. Persistence of only the dorsal portion would leave a dorsal enteric sinus or cutaneous cyst of endodermal origin. Any intermediate type of dorsal enteric sinus or cyst may also develop with concurrent formation of vertebral anomalies, based on the variable persistence and obliteration of any portion of the neurenteric connection. Although this theory presents an understandable mechanism of development, it does not explain all variants of neurenteric cysts, such as those reported in an intracranial location.34

as neurenteric cysts, dorsal enteric fistulas, or split cord malformations, as in diastematomyelia. Bentley and Smith4 expanded on Bremer’s theory, proposing the splitting of the notochord may be the primary event in this process. The resulting deficiency in the overlying neural plate could allow for herniation of endodermal elements through the spinal column to the surface ectoderm. Later obliteration or persistence of portions of this neurenteric connection would then allow for a variety of clinical presentations (Figs. 203-1 and 203-2). By this theory, involution of all but the ventral portion of the connection would result in a duplication or diverticulum of the alimentary canal. Persistence of only the dorsal portion would leave a dorsal enteric sinus or cutaneous cyst of endodermal origin. Any intermediate type of dorsal enteric sinus or cyst may also develop with concurrent formation of vertebral anomalies, based on the variable persistence and obliteration of any portion of the neurenteric connection. Although this theory presents an understandable mechanism of development, it does not explain all variants of neurenteric cysts, such as those reported in an intracranial location.34

Neurenteric Cysts

Clinical Presentation

The age at presentation ranges from the newborn period to adulthood; however, most cases of neurenteric cysts present within the first year of life. Nine of 15 cases reported by Superina41 were in patients under 1 year of age. Fetal diagnoses have been made of large mediastinal neurenteric cysts demonstrated by prenatal ultrasonography.10,37 In the future, most cases are likely to be recognized by prenatal evaluation. Referral of the mother to a pediatric surgical center is appropriate to enable prompt postnatal management.

The presenting symptoms are determined by the size and location of the cyst and by the effect of expansion on the mediastinal or spinal structures. Occasionally, lesions are asymptomatic and are incidentally observed on chest radiography. Ahmed and coworkers1 reported that respiratory symptoms, presence of a mediastinal mass, and a vertebral anomaly form a triad present in 70% of patients. As noted by Alrabeeah and associates,2 the signs and symptoms of neurenteric cysts are related most frequently to the compressive effect of the mass on the airway. Dyspnea, cough, stridor, and respiratory distress are observed frequently. Many infants become symptomatic shortly after birth as the lesion fills with fluid, expands, and compresses vital surrounding structures. The cysts also may be symptomatic if they contain ectopic gastric mucosa. Kropp and colleagues19 emphasized that if the cyst has a communication with the gastrointestinal tract below the diaphragm, acid secretion may lead to ulceration and gastrointestinal bleeding.

Most cases of neurenteric lesions reported in the literature have been identified in the mediastinum with a spinal anomaly or extension into the spinal canal without medullary involvement. The associated spinal abnormalities are usually located in the lower cervical and upper thoracic regions. Many authors have noted that these anomalies can include hemivertebrae, fused vertebrae, anterior spina bifida, or an intraspinal mass.3,9,36 Most neurenteric cysts have only a fibrous attachment to the vertebral column. However, several cases have been reported in which the lesion had minimal mediastinal involvement and presented as a neurologic problem from intraspinal compression by the mass. Menezes and Ryken26 noted cysts in the ventral aspect of the cervical spinal canal. In addition, Elwood8 reported a case of a mediastinal neurenteric cyst with a cystic swelling in the spinal column with no communication across the vertebrae. Neurologic symptoms, although less common at presentation, can include back pain, sensory or motor deficits, and gait disturbance. Symptoms of meningeal irritation may occur also. Sequelae of an intraspinal mass are reflected in a reported case of a 2-year-old boy developing progressive weakness of his lower limbs, resulting in severe spastic paraplegia. A complete block was noted at the T6 level on myelography. At exploration, a gastric mucosa–lined cyst in the paravertebral sulcus with intravertebral extension was noted.32

Pathology

The intraspinal component of a neurenteric cyst has been described by D’Almeida and Stewart6 as a thin-walled structure with a single layer of columnar epithelium supported by a thin sheath of connective tissue. In a review of the literature by Lerma and colleagues,22 the majority of cysts contained a single layer of nonciliated mucin-producing columnar or cuboidal epithelium with an occasional cyst lined with pseudostratified or squamous cells. Several lesions also have been described with either intraspinal cysts consisting of a replica of the stomach wall or with typical small bowel mucosa.18,36 The presence of keratin markers and mucus-secreting cuboidal or columnar epithelium in three cases of intraspinal neurenteric cysts has confirmed the ectodermal and endodermal origin of these cysts.20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree