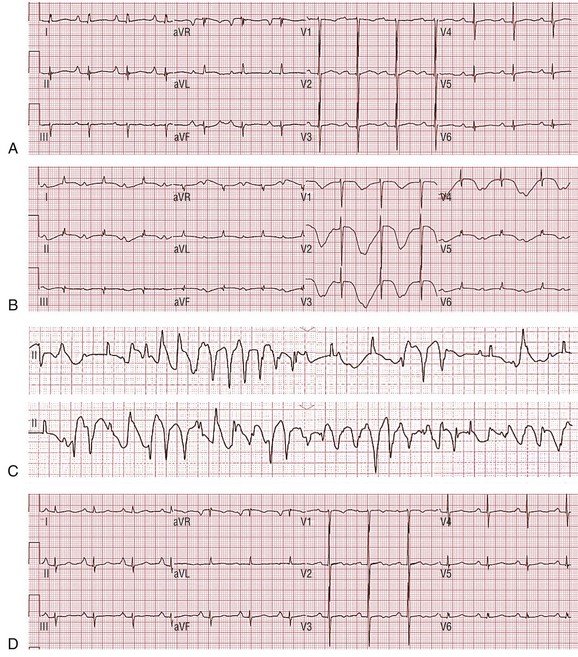

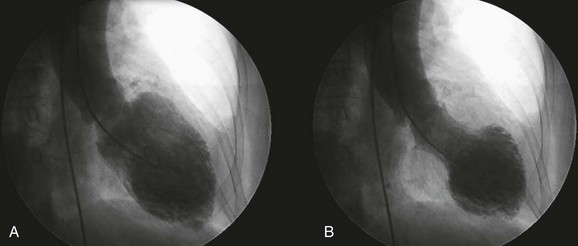

91 Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TCM) is a syndrome characterized by transient ventricular dysfunction in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease.1–4 Also known as stress cardiomyopathy or apical ballooning syndrome, TCM most commonly occurs in the setting of severe emotional or physical stress. The exact mechanism of the transient cardiomyopathy remains undefined; however, it is believed that ventricular dysfunction is induced by catecholamine-mediated myocardial toxicity.5–7 The clinical profile of TCM has been well described in several case series.1,3,4,8 Upon presentation, electrocardiographic (ECG) changes resemble those seen in acute coronary syndromes, including ST elevation. Most patients with typical left ventricular (LV) apical involvement develop repolarization abnormalities within 24 to 48 hours of presentation. These abnormalities include diffuse T wave inversions (TWIs) and QT prolongation, the latter often quite pronounced.9–12 It is evident that TCM should be considered among the causes of acquired long QT syndrome (LQTS).9,13,14 Long QT syndrome can be associated with sudden cardiac death (SCD) from the distinctive reentrant polymorphic ventricular tachyarrhythmia, torsades de pointes (TdP), which can degenerate to ventricular fibrillation (VF). Despite the severe repolarization abnormalities seen in TCM, the mechanism of life-threatening arrhythmias remains incompletely understood and the risk uncertain. This chapter describes the clinical circumstances and explores the pathogenesis underlying ventricular arrhythmias in the setting of TCM. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is a reversible form of LV dysfunction that is most commonly triggered by emotional or physical stress. First reported in Japan, the term “takotsubo” describes the shape of the LV during systole in the most typical form of the disorder.15–17 Akinesis or hypokinesis of the apical and midventricular segments with hyperkinesis of the base results in a balloon-like appearance of the LV resembling the traditional Japanese octopus trap (Figure 91-1). Although the clinical profile for TCM can be broad, a clear age- and gender-specific phenotype has been identified. Elderly, postmenopausal women seem to be most at risk, accounting for more than 80% of cases in most series.1,2 As noted, TCM is most frequently precipitated by an intensely emotional or physical event; however, in a relatively large minority of cases, no identifiable trigger is obvious.1,2,18–20 Figure 91-1 The left ventriculogram in a patient with takotsubo in the right anterior oblique projection (A, end-diastole; B, end-systole). An extensive area of akinesis involving the apical and midventricular segments with hyperkinesis of the base results in a balloon-like appearance of the left ventricle. The actual incidence of TCM is difficult to quantify, but it appears to account for approximately 1% to 2% of all cases of suspected acute coronary syndrome.21,22 Its clinical presentation is often similar to that of an acute myocardial infarction (MI), with symptoms most commonly including chest pain, dyspnea, and syncope.1,2 Some patients can be critically ill on presentation as the result of acute pulmonary edema, hypotension, cardiogenic shock, or an arrhythmic arrest (VF or asystole). ECG changes resembling those seen in acute coronary syndromes, including ST elevation, direct most patients to coronary angiography. Takotsubo is usually diagnosed when coronary angiography demonstrates normal vessels or nonobstructive disease and when assessment of LV function reveals regional wall motion abnormalities extending beyond a single epicardial vascular distribution. Myocardial dysfunction most commonly results in apical ballooning; however, other distinct patterns of regional myocardial involvement have been described in a minority of patients, including midventricular and basal distributions.20,23–25 Right ventricular involvement has also been reported.26 Myocardial enzymes are usually elevated only to a mild or moderate degree.1 Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in confirming the diagnosis and in revealing typical patterns of LV dysfunction and myocardial edema and the absence of significant necrosis/fibrosis.20,25 Despite marked initial LV dysfunction with potential sequelae such as heart failure, shock, thromboembolism, and even ventricular free wall rupture, the overall prognosis in TCM is quite good.1,27 Most patients experience a favorable outcome with supportive care. In-hospital mortality rates tend to be less than 3% in most large series.1,2,20 Patients typically recover normal LV function within days to weeks.5 Delayed normalization (months) has been observed in a minority of patients.1 Recurrence rates of TCM can be as high as 5% to 11% in some large series.1,28 All-cause mortality in survivors of TCM was elevated during the follow-up period in one series, with all deaths attributed to noncardiac causes.1 This higher mortality rate was not apparent in another series.28 The ECG changes in TCM have been systematically evaluated.11,12,29–31 On admission, ST elevation mimicking acute MI is the most common finding, ranging from 37% to 90% in large series.1,16,20 Other ECG findings on admission can be diverse and include ST depression, TWIs, a healed anterior MI pattern, bundle branch block, nonspecific findings, or a normal appearance.1 Kosuge et al. compared presentation ECGs of 33 TCM patients with those of 342 anterior MI patients. They found that TCM was associated with a lower maximal ST elevation and a greater number of leads with ST segment elevation compared with anterior MI.32 Specifically, TCM was more frequently associated with ST segment elevation in leads I, II, III, aVF, and, especially, aVR. In contrast, TCM was less frequently associated with ST segment elevation in leads aVL and V1 to V4 (particularly V1). Additionally, abnormal Q waves (58% vs. 74%; P = .048) and reciprocal changes (6% vs. 49%; P < .001) were less frequent in TCM patients.32 The ECG in TCM appears to evolve with the clinical course of the disorder. ST segment elevation evident in the acute phase usually returns to normal within 3 days of onset.11,12 In the subacute phase (days 1 to 3 post admission), TWI is frequently observed. As compared with MI, TCM is associated with a wider distribution and greater maximal amplitude of negative T waves.33 In TCM, negative T waves were consistently observed in leads aVR and V4 to V6, whereas negative T waves were less likely in lead V1. The TWI appears to progress and deepen, with the negative peak usually occurring 2 to 3 days post admission.9,11,12 The TWI subsequently improves; however, in some patients, a second stage of TWI can be observed that can persist for days to weeks, even after ejection fraction and wall motion abnormalities have normalized.11,12 A similar biphasic pattern has been described in patients with MI who develop deep TWIs.34 Repolarization changes in TCM also involve QT interval prolongation, which often appears to follow a time course that mirrors T wave changes. The QT interval is frequently increased on admission ECG and continues to lengthen, with peak prolongation occurring 2 to 3 days post admission (subacute period).9,11,12,29 The combination of QT prolongation, which can be extreme, and inverted T waves can produce the pattern of a giant TWI.9,31 Subsequently, QT prolongation lessens in conjunction with improvement in TWI. In patients who display a biphasic TWI pattern, the QT interval lengthens again, but not to the degree seen during the subacute phase.11,12 The exact time course of QT prolongation is not well defined, but repolarization changes can persist for weeks beyond LV wall motion recovery.11,12 The ECG patterns discussed previously are regularly observed in the typical apical ballooning form of TCM. ECG findings in the rarer, variant forms of TCM are less well defined but appear to be different. ST elevation and TWI are less frequent in midventricular and reverse (basal distribution) TCM.24,35 The issue of ventricular arrhythmias in TCM—the main focus of this chapter—is discussed in the following sections. Supraventricular arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation and supraventricular tachycardia, have also been described in this disorder and are likely attributable in part to high levels of circulating catecholamines.36,37 Bradycardia and heart block have also been reported.14,36,38 Ventricular arrhythmias in the setting of TCM are increasingly recognized as an important clinical entity. They include ventricular tachycardia (VT), VF, and TdP.36 Despite the severe repolarization abnormalities observed in TCM, the arrhythmic risk remains relatively low. The reported prevalence of ventricular arrhythmias in TCM varies between series. The incidence of ventricular arrhythmias ranges from <1%1 in some series to 8.9% in a smaller report.9 In a comprehensive literature review, Syed et al. reported a sustained VT or VF frequency of 3.4%.36 Although TCM is a reversible cardiomyopathy with generally a good prognosis, it is essential for the clinician to understand the clinical circumstances associated with ventricular arrhythmias, as these can prove fatal. The mechanisms of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia in TCM remain incompletely understood; however, a clinical profile of arrhythmic risk is developing. TCM appears to follow a characteristic time course that consists of acute, subacute, and healing phases.11,12,29 It is becoming evident that arrhythmic risk is variable throughout the time course of TCM and that the mechanism of ventricular arrhythmias differs between acute and subacute phases.9 In the subacute phase of TCM (24 to 48 hours post presentation), the most common mechanism of ventricular arrhythmia appears to be pause-dependent TdP or VF associated with QT prolongation (Figure 91-2).9,14,39 As noted, the association between QT prolongation and TCM is well described. The prevalence of QT interval prolongation among TCM patients is high, ranging from 50% to as high as 100% in different case series.14 In the typical apical ballooning form, QT prolongation is often associated with deep TWI.31 Longer maximal QT intervals appear to occur more commonly in patients with giant negative T waves.29 Although QT prolongation can also be observed at presentation, the arrhythmic risk associated with TCM appears to be highest during the subacute period, when QT prolongation is associated with maximal TWI.11,12,29

Ventricular Arrhythmias in Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy

Clinical Characteristics of Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy

Electrocardiographic Changes

Ventricular Arrhythmias

Ventricular Arrhythmias in Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy