Chapter 3 Venous Pathophysiology

Etiology and Natural History of Disease

Primary Venous Disease

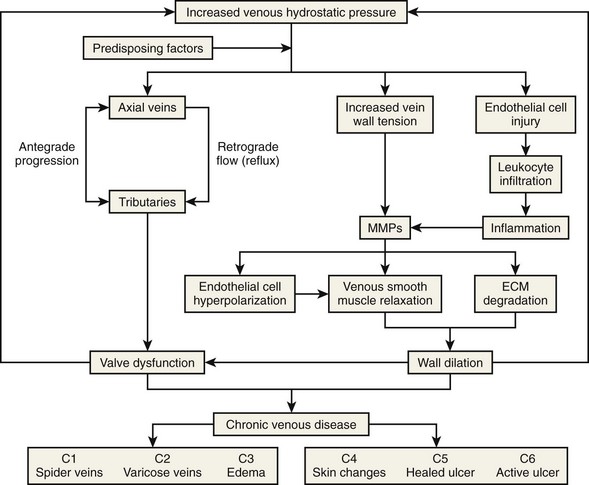

Primary venous disease affects two-thirds of patients with chronic venous disease (CVD). The most accepted theory is based on increased venous hydrostatic pressure transmitted to the vein wall, causing smooth muscle relaxation, endothelial damage, and extracellular matrix degradation with subsequent vein wall weakening and wall dilatation.1 It has also been suggested that valve damage may occur because of local inflammation.2 Leukocyte migration, plasma-granulocyte activation, and increased activity of metalloproteinases causing degradation of the valve leaflets support that theory.2,3 Figure 3-1 summarizes the pathophysiologic pathways of CVD.

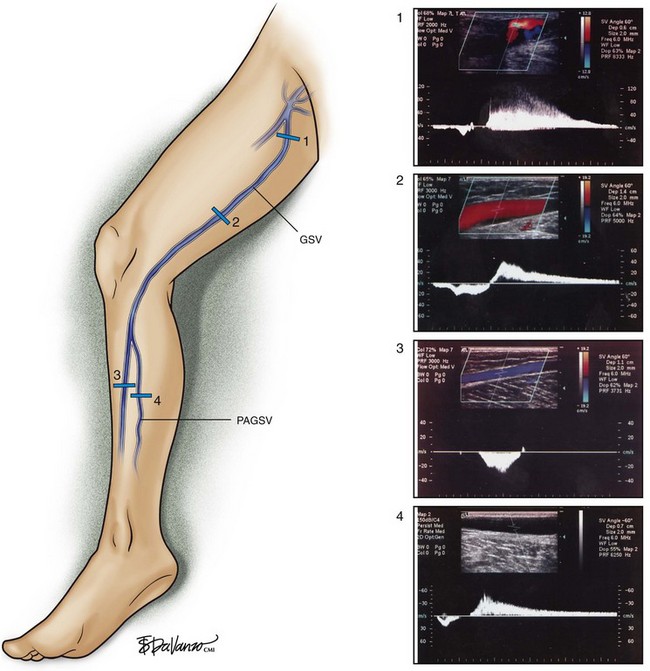

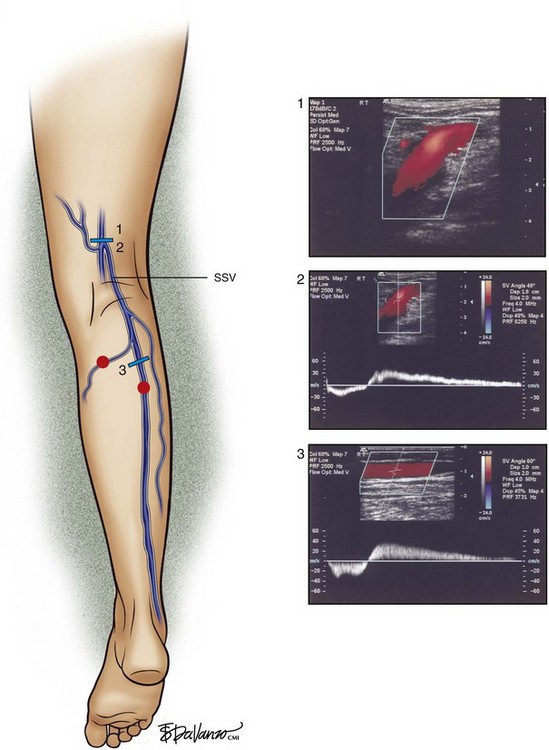

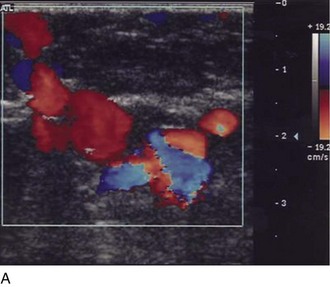

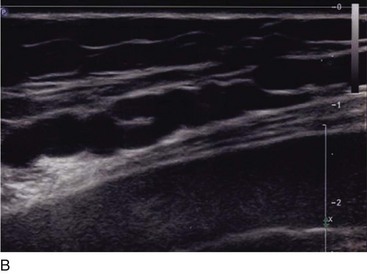

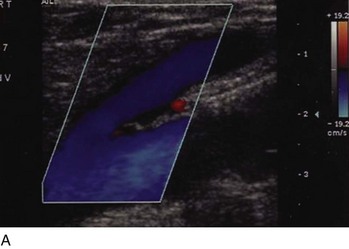

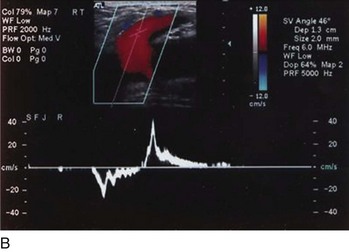

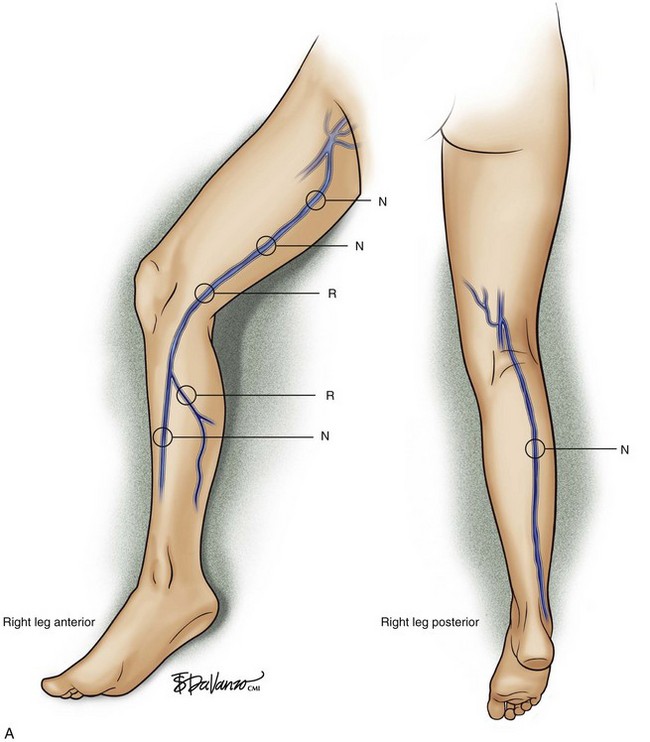

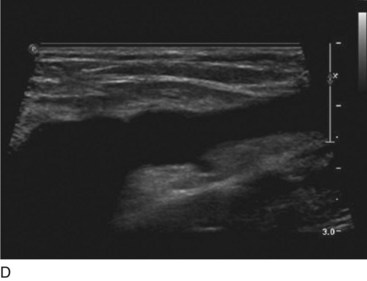

Superficial veins are most commonly involved in primary CVD, followed by perforators and deep veins.4 It has been shown that reflux starts in superficial veins in more than 80% of the patients. In the early stages of CVD, reflux is found in the great saphenous vein (GSV) and its tributaries without almost any junctional involvement (Fig. 3-2). This is followed by reflux in the small saphenous vein (SSV) system (Fig. 3-3) and nonsaphenous veins (Fig. 3-4). Patients with competent saphenous, perforators, and deep veins may also present tributary reflux in 10%, with the GSV tributaries being affected in 65% of the cases.

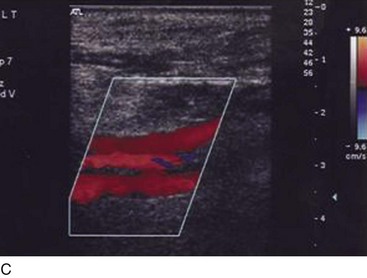

Isolated primary deep vein reflux is rare. It may present as either segmental or axial reflux extending from the femoral vein in the thigh to the below-knee popliteal vein. The most frequent location of primary deep vein reflux is the common femoral vein, followed by the femoral and popliteal veins5 (Fig. 3-5). Because most deep venous reflux is deemed to be caused by superficial venous reflux propagation, both common femoral and femoral vein reflux are associated with GSV incompetence and popliteal vein reflux is associated with SSV and/or gastrocnemial vein incompetence5 (Fig. 3-6). In addition, deep vein reflux has a shorter duration compared with superficial venous reflux. Association between deep and superficial venous reflux ranges from 5% to 38%.5–8

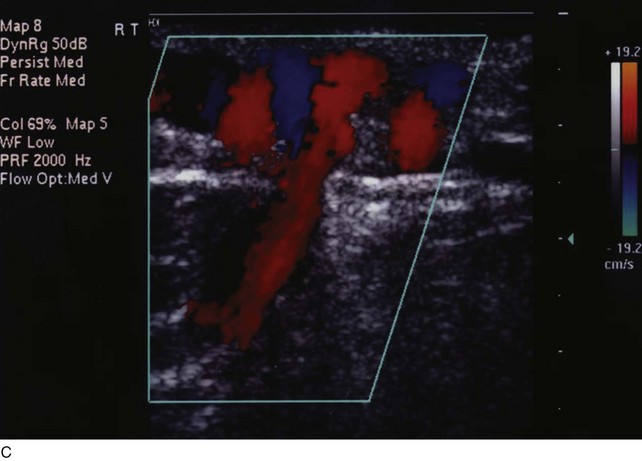

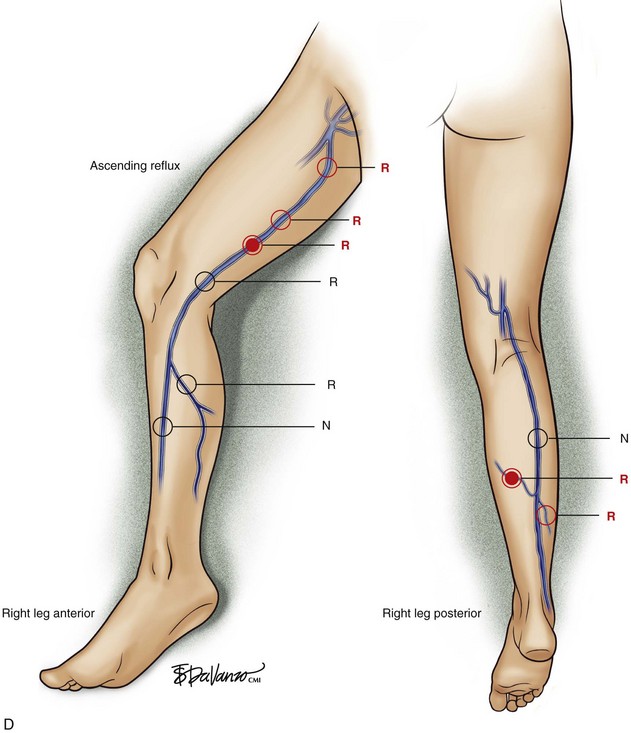

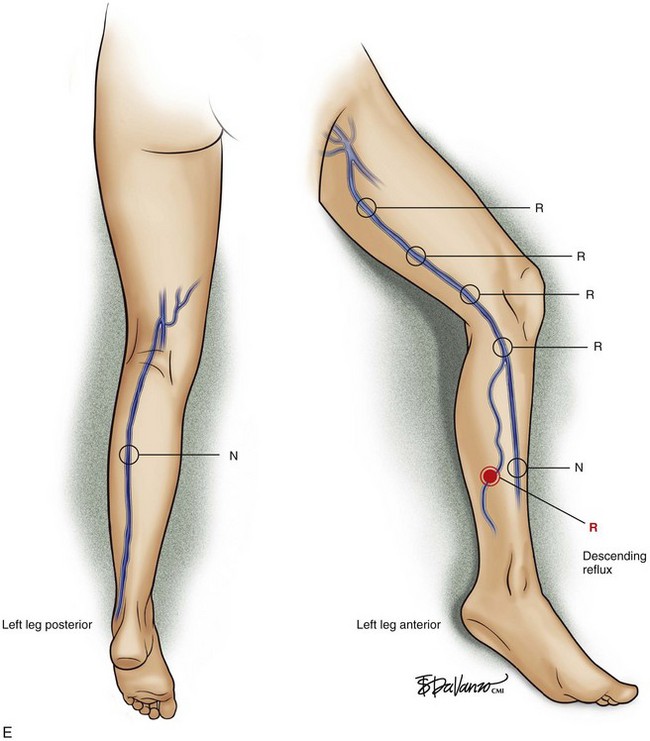

Perforator vein (PV) reflux in primary CVD always occurs in association with superficial vein reflux.9 Essentially, PVs become incompetent secondary to either ascending extension of superficial vein reflux or descending propagation of the reflux in a reentry fashion (Fig. 3-7). Most often, PV reflux originates from the GSV system and renders the deep veins incompetent in 13% of the cases.9 Deep vein reflux secondary to PV reflux is usually segmental and has a short duration.9

Secondary Venous Disease

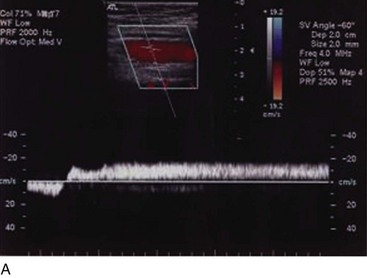

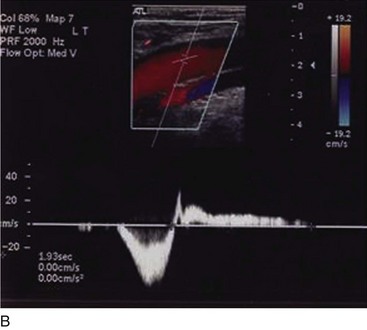

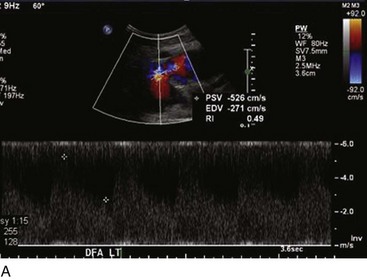

Secondary venous disease is caused by a thrombotic event or is secondary to trauma. The incidence of arteriovenous fistula (AVFs) as cause of secondary CVD is reduced compared with postthrombotic CVD (Fig. 3-8).

Most frequently, AVFs are created when both common femoral vessels are inadvertently punctured during endovascular procedures or secondary to penetrating or blunt traumatic injuries. Animal models based on AVF creation have been used to explain the findings of chronic venous disease.10 Initially, lower resistance in the distal portion of the artery and pulsatile flow in the vein are noted. Venous hypertension supervenes, distending the veins and causing some degree of edema in the limb but no reflux. Subsequently, the valves are unable to appose what portends the reflux. Continuous venous hypertension and reflux entail valve atrophy and “arterialization” of the venous wall in the long term. In humans, the occurrence of CVD secondary to AVFs is rare and requires a long course to generate clinical impairment that frequently is devastating.

Regardless of the initial thrombi formation, the majority of the limbs evolve with thrombus resolution. Notably, only one-third of the patients with secondary CVD develop postthrombotic syndrome (PTS), which consists of signs and symptoms such as pain, edema, heaviness, and intolerance to efforts that may progress to skin changes and ulcers (Fig. 3-9). Often, patients with PTS have a combination of reflux and obstruction (Fig. 3-10). PTS represents the most severe manifestation of secondary CVD, carrying significant socioeconomic impact, and is discussed in Chapter 15.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree