Venous Disorders and Venous Thromboembolism

A spectrum of chronic venous disorders, from simple varicose veins to venous stasis ulcers, afflicts at least 20% to 25% of the population. Varicose veins are one of the most common vascular problems seen in office practice. Most varicose veins are the result of a congenital or familial predisposition that leads to loss of elasticity in the vein wall and the absence or incompetence of venous valves. These primary varicosities generally progress downward in the saphenous system. Prolonged standing, obesity, and pregnancy make all leg varicosities more symptomatic.

Most patients who have had femoropopliteal deep vein thrombosis will develop some degree of post-thrombotic syndrome. Thrombosis damages deep venous valves and often leaves them incompetent. The musculovenous pump can no longer reduce ambulatory venous pressures. Consequently, the patient has chronic venous hypertension in the leg when he or she stands with high venous pressures transmitted through perforating veins from the deep to superficial venous system. In 20% to 50% of patients with symptoms and signs of chronic venous insufficiency, no history of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is obtainable. The classic physical findings are a chronically indurated ankle, dark stasis pigmentation around the ankle, and skin ulceration in some patients. The exact means by which this chronic venous hypertension causes stasis skin changes and ulceration is still unclear. Evidence suggests that local capillaries leak fibrinous protein that is not adequately removed by fibrinolysis. A liposclerosis occurs and local tissue oxygen diffusion may be impeded. The result is tissue necrosis and skin ulceration. Skin ulceration seldom occurs unless the popliteal vein valves are incompetent.

Post-thrombotic syndrome or primary deep valvular incompetence can be especially disabling for active ambulatory workers, since leg dependency increases pain and swelling and impedes ulcer healing. Fortunately, proper elastic leg support, skin care, and, in some situations, surgery can alleviate chronic venous insufficiency enough that patients can remain comfortable and active. In patients with chronic iliofemoral venous obstruction, venous capacitance is increased at rest and cannot compensate during exercise. The result is severe thigh pain and a sensation of tightness with vigorous exercise, dubbed venous claudication. Leg symptoms are more common in patients with chronic venous obstruction than in those who have recanalized veins with incompetent valves. A surprising observation is that 5 to 10 years after lower-extremity DVT, over 80% of patients will develop some symptoms of chronic venous insufficiency (edema, pain, ulceration).

The current clinical approach to acute venous thromboembolism focuses on prevention, rapid diagnosis, and treatment. A better understanding of the pathophysiology of DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE) has resulted in more aggressive

preventive measures. The limitations of the physical examination in accurate diagnosis of venous thromboembolism have culminated in the development of efficient, noninvasive methods for detection. Newer anticoagulant medications and regimens offer alternatives for prevention and treatment. Finally, clinical trials will define the role of catheter-directed thrombolysis in the treatment of DVT.

preventive measures. The limitations of the physical examination in accurate diagnosis of venous thromboembolism have culminated in the development of efficient, noninvasive methods for detection. Newer anticoagulant medications and regimens offer alternatives for prevention and treatment. Finally, clinical trials will define the role of catheter-directed thrombolysis in the treatment of DVT.

I. Chronic venous disorders.

A.

The CEAP classification scheme (see Table 2.1) has been adopted worldwide in order to standardize and facilitate communication about chronic venous disorders. Venous disease is defined by clinical class (C), etiology (E), its anatomic (A) distribution in the veins, and the pathologic mechanism (P) of development (reflux or obstruction or both).

1. Clinical presentation of venous disorders relies upon physical examination. C1 disease is evidenced by telangiectasias and/or reticular veins, commonly referred to as spider veins. Varicose veins are distinguished by diameter <3 mm and their characteristic protuberance and are seen in C2 disease. Progression to edema and skin changes from venous hypertension is seen with C3 and C4 disease, respectively. Skin changes may be mild such as eczema or erythematous dermatitis. Lipodermatosclerosis is a localized chronic inflammation and fibrosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissues of the lower leg, occasionally associated with scarring of the Achilles tendon. Lymphangitis and cellulitis should be differentiated by local signs and systemic features. Atrophie blanche, or white atrophy, refers to the smooth, stellate scarring that can occur with venous stasis. The most severe clinical manifestation is venous ulceration. A healed ulcer is seen in C5 disease. An active ulcer with a full thickness skin defect, most frequently in the ankle region, defines C6 disease.

2. The etiology of the venous disease is also used for classification. Venous disease may be congenital, as in Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome, which appears to be a fetal developmental abnormality. The classic clinical triad includes (a) port-wine stains, (b) hypertrophy of soft tissue and bone with overgrowth of the extremity, and (c) varicose veins. Because of the benign course of this disease, the majority of these patients do not have surgery and do well with conservative therapy. Occasionally, a more aggressive operative approach may be necessary in patients with large, symptomatic varicosities, especially if hemorrhage or ulceration has occurred. It is important to rule out deep venous hypoplasia, which can be present in these patients, prior to any treatment of superficial varicosities. Venous disease may also be primary from the degeneration of valves or secondary as a result of damage from prior thrombosis (post-thrombotic).

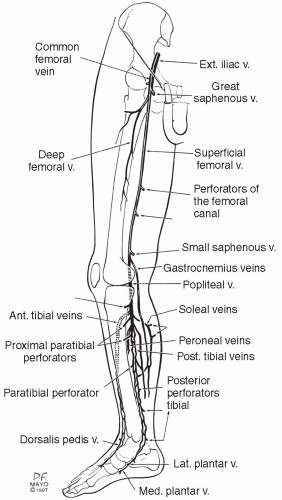

3. Anatomically, venous disease can roughly be classified as superficial, deep, and/or perforating veins. The affected veins cannot be accurately defined by physical exam alone. Duplex ultrasound is necessary if precise identification of the involved veins is desired (Chapter 6).

4. The pathophysiology of venous disease is from reflux, obstruction, or a combination of the two. Reflux can develop primarily or as a result of post-thrombotic degeneration of valves. Obstruction is most commonly a post-thrombotic event, and may occur when the affected vein is only partially recanalized. The residual webs and synechiae prevent normal venous flow. May-Thurner syndrome is a congenital obstruction of the left iliac vein by the anatomic crossover of the right iliac artery. In some patients, this impingement may result in pain (venous claudication), edema, and a predisposition toward developing left iliofemoral venous thrombosis. It is interesting that over 20% of the population demonstrates this compression in cadaver studies, but only a minority becomes symptomatic.

B. Diagnosis

1. Clinical presentation. Varicose veins present with unsightly bulges on the lower extremity and often with associated achiness or heaviness in the legs with prolonged standing. Symptoms may not correlate well with the degree of anatomic defect. Occasionally, a patient will abrade a varicosity, which may cause a rather impressive hemorrhage. A more common complication of varicose veins is superficial thrombophlebitis, which may cause considerable pain and disability but rarely leads to PE. Longstanding varicose veins may also result in chronic ankle induration, stasis dermatitis, and, occasionally, leg ulcerations. As was previously noted, post-thrombotic syndrome is found in patients with a history of DVT leading to deep venous insufficiency and/or obstruction. This syndrome is manifested by skin changes, edema, and ulceration of the lower extremity.

2. Noninvasive venous testing is very helpful in the diagnosis of both acute and chronic venous disease as described in Chapter 6. Duplex ultrasound is the mainstay of diagnosis. Reflux in the superficial and deep veins can be determined by prolonged valve closure times (>0.5 seconds). Perforator incompetence is determined by reversed or outward flow (deep to superficial) in the perforating veins of the leg. Duplex has greater than 95% accuracy in the detection of acute venous thrombosis, and can also recognize the signs of chronic thrombosis, such as recanalization, collaterals, and more echogenic clot. Plethysmography can provide a global assessment of the limb’s venous function and is generally applied as an adjunct to Duplex in more severe cases of chronic venous insufficiency. CT and MR venography are particularly useful in evaluation of the central veins, which are less accessible by ultrasound. However, both CT and MR can only determine anatomic abnormalities and provide no physiologic evaluation. MR is the test of choice for characterization of venous malformations. Invasive venography is

generally reserved for those patients with chronic venous insufficiency or congenital disorders in order to evaluate for venous reconstruction. Ascending venography provides a roadmap of the limb and central drainage, such that obstructive lesions can be identified. Descending venography can localize incompetent valves and assess the severity of the reflux.

generally reserved for those patients with chronic venous insufficiency or congenital disorders in order to evaluate for venous reconstruction. Ascending venography provides a roadmap of the limb and central drainage, such that obstructive lesions can be identified. Descending venography can localize incompetent valves and assess the severity of the reflux.

C. Treatment.

1. Nonoperative treatment is appropriate for the majority of chronic venous disorders. The symptoms may range from mild (varicose veins) to severe (ulcers). Patients should be reassured that the presence of chronic venous disease is neither life- nor limb-threatening. In our experience these are frequently the unspoken concerns of our patients. Even severe venous ulceration is usually superficial and does not threaten the limb in the absence of superimposed infection or arterial insufficiency. Chronic venous insufficiency is incurable, thus it is important that the patient understands that the goal of treatment is to minimize symptoms and prevent ulcer recurrences.

The following measures will promote venous health for patients with chronic venous diseases:

Compression therapy with graduated stockings

Elevate the feet and legs for 10 to 15 minutes whenever possible

Walk to improve the musculovenous pump of the calf

Avoid trauma to varicose veins

Weight reduction for obese patients

Avoid prolonged standing or sitting

Consultation with vascular and wound care specialist at the first signs of ulceration or cellulitis

Maintain skin integrity, avoiding cracking and eczema, with proper emmolients

a. Compression therapy is the mainstay of medical treatment for all chronic venous disorders. Graded elastic stockings are available in a variety of strengths, lengths, and styles. Strengths of 20-30 mm Hg are most commonly prescribed for varicose veins and milder venous disorders. The stockings alleviate many of the symptoms of leg achiness, heaviness, and swelling. Although below-the-knee stockings are suitable for most patients, some women with varicose veins prefer a high-quality sheer panty hose with graduated pressure from the ankle to waist. Several companies offer specialized venous stockings and hosiery [e.g., Sigvaris (Ganzoni and Cie, AG, St. Gallen, Switzerland), Jobst (Beiersdorf-Jobst Inc., Charlotte, NC, U.S.A.), and Medi (Medi USA Inc., Whitsett, NC, U.S.A)].

Patients with post-phlebitic syndrome and deep venous insufficiency are often affected by ambulatory venous hypertension. In such patients venous pressures decrease only 20-30% during exercise compared with a 70% decrease in the setting of normal venous function. Venous pressures are highest in the most dependent portion of the leg at the ankle, where most

post-thrombotic changes occur. Although chronic venous hypertension cannot be corrected by elastic leg support, elastic leg support can prevent some of the leg edema. For these patients, strengths ≥30-40 mm Hg are desirable. Below-the-knee stockings are generally sufficient in most patients for several reasons. First, post-thrombotic problems nearly always occur below the knee, where venous pressures are highest. Thigh swelling seldom is a problem after acute DVT has resolved. Second, support hose that comes above the knee often binds or constricts the popliteal space, especially if the hose slip down the leg. Third, patients generally do not like a heavy support hose that covers the entire leg. Many patients who are given full-length or pantyhose-type heavy support hose will wear them only when visiting their physician for a check-up. However, some patients with vena cava occlusion and severe leg swelling to the waist will need full-leg heavy support hose and will wear them without complaint.

post-thrombotic changes occur. Although chronic venous hypertension cannot be corrected by elastic leg support, elastic leg support can prevent some of the leg edema. For these patients, strengths ≥30-40 mm Hg are desirable. Below-the-knee stockings are generally sufficient in most patients for several reasons. First, post-thrombotic problems nearly always occur below the knee, where venous pressures are highest. Thigh swelling seldom is a problem after acute DVT has resolved. Second, support hose that comes above the knee often binds or constricts the popliteal space, especially if the hose slip down the leg. Third, patients generally do not like a heavy support hose that covers the entire leg. Many patients who are given full-length or pantyhose-type heavy support hose will wear them only when visiting their physician for a check-up. However, some patients with vena cava occlusion and severe leg swelling to the waist will need full-leg heavy support hose and will wear them without complaint.

Compliance with compression therapy is particularly important for patients with active or healed venous ulceration. Active venous ulcers heal at an average of 5 months in 97% of compliant patients compared to 55% of patients who are non-compliant. Continued compression therapy also significantly reduces the incidence of ulcer recurrence. Several suggestions should be offered to the patient to ensure the proper and comfortable use of heavy support hose. First, the hose should be put on in the morning, prior to ambulation. Otherwise, early leg swelling may begin before the elastic support can control it. This routine usually requires that the patient bathe or shower before going to bed at night. Second, heavy hose may be difficult to slide on the leg, especially for patients who have difficulty applying the stockings due to hand arthritis or poor conditioning. Special stocking-donning devices are commercially available. The stocking can be loaded onto the donning device, which stretches it sufficiently for easier application. A silky liner or light nylon hose worn beneath the heavy stocking can also make application easier. Third, elastic support hose must be properly fitted, or the patient will not wear them. Patients with large or unequal leg size may need custom-fitted stockings. We encourage patients to contact the fitting shop for adjustments if their new hose do not fit satisfactorily. We also periodically recheck patients in the outpatient clinic to ensure that their hose fit properly. In general, most heavy elastic support hose will need to be replaced every 6 to 12 months.

b. Leg elevation remains a simple and effective method of alleviating ankle edema. Patients with post-thrombotic syndrome should elevate their legs above the level of the heart for 10 to 15 minutes every 2 to 4 hours during the day. This recommendation may seem impractical for the working individual, but most workers are allowed breaks during their normal work hours

at which time elevation can be done. Periodic leg elevation allows most patients to remain comfortable during work. An explanatory note from the physician to the patient’s employer often avoids any problem that the patient may encounter by periodically sitting down on the job.

at which time elevation can be done. Periodic leg elevation allows most patients to remain comfortable during work. An explanatory note from the physician to the patient’s employer often avoids any problem that the patient may encounter by periodically sitting down on the job.

c. Skin care is important if dermatitis, local infection, and ulceration are to be prevented. Scaly pruritic skin of the foot or ankle may indicate fungal infection, which is managed by a topical fungicide such as Baza® antifungal cream (2% miconazole nitrate, Coloplast Corp., Marietta, GA) or Lotrimin® (1% clotrimazole, Schering-Plough Corporation, Kenilworth, N.J.). Eczematous stasis dermatitis may be alleviated by a topical steroid cream, such as hydrocortisone cream 1%. Routine leg washing should be done with warm water and a mild soap. We discourage soaking the leg, since this may macerate friable skin and increase swelling due to dependency of the extremity. Non-perfumed emmolients such as Aquaphor® or Eucerin® (Beiersdorf, Wilton, CT) should be used to treat dry, cracked skin to prevent further breakdown, ulceration, and cellulitis.

d. Venous ulcers classically occur in the lower third of the leg above the ankle, referred to as the “gaiter distribution.” Most frequently, ulcers occur at the medial malleolus adjacent a medial ankle perforator. Less commonly, they occur on the lateral or posterior calf at the site of the lateral ankle perforator or the midposterior calf perforator (Fig. 19.1). The treatment of venous ulcers utilizes all of the principles listed previously, however, supplementary measures may be needed to treat refractory ulcers. A compressive bandage should be applied over the ulcer dressing (Fig. 19.2). A rigid bandage can provide a greater amount of continuous compression than a stocking, and is a good adjuvant technique for nonhealing ulcers. The Unna boot is the most well known of these rigid bandages. The three-layered boot is applied by a medical professional. The innermost layer is a medicated paste gauze that contain calamine, zinc oxide, glycerin, sorbitol, and magnesium aluminum silicate. The second layer is gauze, followed by an outer elastic compression wrap. The boot hardens and can be left on for a week, although more frequent checks (e.g., every 2-3 days) of the leg should be performed in diabetic patients or those with resolving cellulitis. The advantage of a boot is that continuous compression is applied and patient compliance is enforced. An absorbent dressing can be applied to the ulcer before applying the boot. The Profore system (Smith and Nephew, London, U.K.) is a four-layer, commercially available bandage that works by the same principles and is also effective for venous stasis ulcers.

Meticulous wound care is a critical part of the treatment of venous ulcers. A nurse or midlevel provider dedicated to the performance of wound care and able to devote time to counseling is an invaluable asset. The vascular specialist must be committed to supervising the wound care for these patients who require lifelong maintenance. Various ointments, salves, and dressings are available for comprehensive wound care. Clean, granulating wounds should be treated with a hydrogel or hydrocolloid dressing to maintain a moist healing environment, and wounds with large amount of necrotic tissue should undergo manual sharp debridement. Treatment with an enzymatic debriding ointment such as collagenase or papain and urea may also be beneficial, but some patients experience discomfort or burning with application. Wounds with large amounts of serous drainage should be treated with application of absorbent dressing or powder, such as calcium alginate. All of these dressings can be applied underneath a compression stocking or boot although we would caution not to use the Unna Boot or Profore systems in the setting of active infection or cellulitis. In such cases, more frequent changes of the wound will be necessary (e.g., once or twice daily). If the ulcer appears infected, evidenced by foul odor, surrounding cellulitis, or increased drainage, a biopsy for quantitative culture can be taken, although superficial wound swabs are discouraged as a multitude of flora will grow from every open wound. Local cellulitis usually responds to a 5- to 7-day course of an empiric oral antibiotic, such as a cephalosporin.

2. Invasive therapies can be used to treat chronic venous disorders that are refractory to compression therapy or in patients who are unable or unwilling to comply

with compression. Indications for treatment include (a) cosmetic concerns, (b) symptoms of achiness, heaviness, pain or edema, (c) bleeding from friable varicose veins, (d) recurrent superficial thrombophlebitis, and (e) venous ulceration. The type of treatment is guided by the severity and location of venous reflux and/or occlusion, as defined by the preintervention duplex. Additional tests (plethysmography, venograms) are obtained in more complex cases, such as those that have had prior venous operations or may require venous reconstruction. Duplex is unnecessary in patients with only spider veins. All patients should obtain well-fitted compression hose, which are worn for at least several weeks after treatment of varicose veins and indefinitely for patients with history of venous ulceration. Preoperative prophylaxis against DVT with 5,000 units of subcutaneous heparin should be considered in patients at higher risk for periprocedural DVT. Risk factors include older age, obesity, hormone replacement or oral contraceptives, smoking, and history of previous DVT.

with compression. Indications for treatment include (a) cosmetic concerns, (b) symptoms of achiness, heaviness, pain or edema, (c) bleeding from friable varicose veins, (d) recurrent superficial thrombophlebitis, and (e) venous ulceration. The type of treatment is guided by the severity and location of venous reflux and/or occlusion, as defined by the preintervention duplex. Additional tests (plethysmography, venograms) are obtained in more complex cases, such as those that have had prior venous operations or may require venous reconstruction. Duplex is unnecessary in patients with only spider veins. All patients should obtain well-fitted compression hose, which are worn for at least several weeks after treatment of varicose veins and indefinitely for patients with history of venous ulceration. Preoperative prophylaxis against DVT with 5,000 units of subcutaneous heparin should be considered in patients at higher risk for periprocedural DVT. Risk factors include older age, obesity, hormone replacement or oral contraceptives, smoking, and history of previous DVT.

a. Sclerotherapy is the injection of a sclerosing agent into the varicose vein to damage its endothelium to cause an aseptic thrombosis, which organizes and closes the vein. We use sclerotherapy as primary treatment for spider veins, reticular veins, and smaller varicosities (<6 mm). Sclerotherapy can also be used to obliterate small residual varicosities that persist after treatment of great saphenous reflux. In contrast, sclerotherapy is not as durable a treatment for large (8 to 12 mm) varicosities that cascade down the entire lower extremity from a completely incompetent great saphenous vein. Sclerotherapy will have limited long-term success in patients with untreated saphenous or deep system reflux, therefore patients with more significant C2 and greater disease should first be evaluated by duplex ultrasound. Complications of sclerotherapy include hyperpigmentation, skin necrosis, thrombophlebitis, and allergic reactions.

The essentials of safe and effective sclerotherapy are as follows:

(1) Relative contraindications to sclerotherapy include use of anticoagulants, ABI <0.7, veins on the foot; veins in fat legs where perivenous reactions may cause painful fat necrosis, and history of strong allergic conditions.

(2) No more than 0.5 mL of the sclerosant (sodium tetradecyl sulfate 0.25% to 3%, hypertonic saline (23.4%), or sodium morrhuate) should be used in any one injection site. A small-gauge (size 25, 26, or 30) needle is used to inject four to six locations at one injection session. Detergent-based agents can also be mixed with room air to make a foam. Foam sclerotherpay has been used to treat larger varicosities as well as C1 disease.

(3) The injection is done while the patient is reclining, not standing. The sclerosant is retained in the vein segment by compressing it above and below the

injection site for about one minute. The injection is stopped if the patient complains of severe local pain, since this suggests extravasation of the sclerosant outside the vein. It is particularly important to have the leg elevated when using foam sclerotherapy to avoid migration of air into the deep venous system or centrally.

injection site for about one minute. The injection is stopped if the patient complains of severe local pain, since this suggests extravasation of the sclerosant outside the vein. It is particularly important to have the leg elevated when using foam sclerotherapy to avoid migration of air into the deep venous system or centrally.

(4) A compressive elastic bandage is applied and the patient is actively ambulated immediately. This ambulation helps the musculovenous pump of the calf to wash out any sclerosant that may have leaked into the deep venous system. Patients are asked to wear the compressive bandage or compression stockings for at least one week following an average injection in small veins.

b. Surgical and endovascular treatment of varicose veins. The treatment of saphenous vein reflux is indicated for symptomatic varicose veins (aching, hemorrhage, superficial thrombophlebitis). The best surgical candidates are active, healthy patients who are not overweight. Some patients simply desire removal of the varicose veins for cosmetic reasons. Occasionally, primary varicose veins lead to leg ulcers. In addition, there is evidence that correction of the superficial reflux in patients with combined superficial and deep reflux improves venous hemodynamics. In a large randomized controlled trial (ESCHAR), eliminating superficial reflux in combination with compression therapy reduced venous ulcer recurrence, although healing rates were not improved compared to compression alone.

(1) Saphenous vein stripping is the traditional method for treating saphenous reflux. Before the operation, the correct limb is marked with an indelible felt-tipped pen or other nontoxic dye while the patient stands. If stab phlebectomy is planned, the sites of varicose clusters are marked with an X.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree