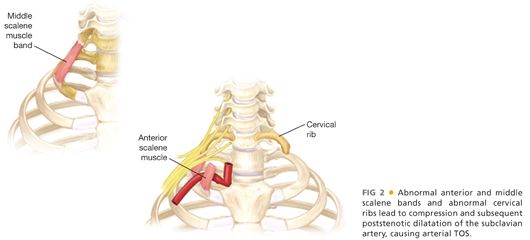

■ Arterial thoracic outlet syndrome (aTOS) is the least common presentation of thoracic outlet syndrome and most often involves subclavian artery compression leading to extrinsic compression, poststenotic dilatation, aneurysmal degeneration, and subsequent distal embolization.1 Bony and muscular abnormalities are typically present in patients with aTOS and can include a cervical rib, anomalous 1st rib, anterior or middle scalene muscle bands, or hypertrophic callus from a healed clavicular injury or fracture (FIG 2).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

■ Compared to neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS), vTOS and aTOS are much more straightforward in their diagnostic workup. vTOS patients with swelling must be distinguished from secondary causes of axillosubclavian thrombosis, namely iatrogenic catheterization or instrumentation of the venous system leading to thrombosis, which is obvious upon eliciting a careful history. Also, a hypercoagulable state or malignancy can present as isolated upper extremity venous thrombosis and there is some debate about the need for additional medical workup in patients suspected of having vTOS.2

■ Because aTOS usually involves distal embolization to the hand from thrombus in a subclavian aneurysm, a thorough workup for a cardiogenic source should be sought before assigning the etiology to aTOS. Transesophageal echocardiography, with bubble enhancement to identify paradoxical emboli, may be necessary to exclude cardiogenic emboli. Computed tomography angiography (CT-A) of the arch and upper extremity vessels would also be reasonable to exclude other arterial causes including axillary branch artery aneurysms, congenital abnormalities, or traumatic injuries and dissections of the axillosubclavian arterial system, which can be seen in high-performance athletes and individuals performing repetitive upper extremity motions.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

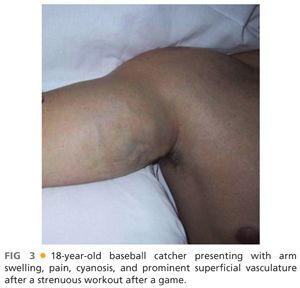

■ Most patients with vTOS are young, healthy, and often athletically inclined who present with the abrupt onset of unilateral arm swelling in their dominant arm after repetitive, strenuous use for sport, work, or recreation. Athletes affected can include baseball pitchers, rowers, swimmers, water polo players, weightlifters, volleyball players, surfers, football quarterbacks, or any others relying on repetitive upper extremity effort. The swelling is noted in the shoulder, arm, and hand and can be accompanied by aching, throbbing, or tightness that worsens with more activity. Because most patients are otherwise young and healthy, an orthopedic cause such as strain, muscle pull, or joint injury is often considered initially. Cyanosis of the affected extremity, visible chest wall venous collaterals, or progressively worsening symptoms suggest a vascular etiology, prompting referral to an interventionalist. On exam, the arm is swollen, tender to palpation, warm, and often has visible superficial collaterals that track onto the anterior chest wall (FIG 3). Range of motion of the affected extremity can be impeded due to patient discomfort.

■ aTOS patients will present with mild hand ischemia due to distal embolization, which manifests as digital ischemia or splinter hemorrhage. The diagnosis is often delayed due to the fact that these patients have no typical atherosclerotic risk factors and are mostly young and athletic. A pulsatile mass or bruit may be present in the supraclavicular fossa or a bony prominence in that region may hint toward a cervical rib or muscular abnormality. Symptoms often are gradual and unnoticed by patients until occurring more frequently or when complete thrombosis occurs and the patient presents with critical upper extremity ischemia.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ Patients suspected of having vTOS should undergo duplex ultrasound of the affected area. Axillosubclavian venous imaging can be challenging due to the clavicle’s location as well as many of these patients being quite muscular. Color flow duplex, phasicity of flow with respiration, and augmentation with compressive maneuvers can all aid in confirming the diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis (DVT). An experienced vascular sonographer and interpreter can make the diagnosis with high accuracy based on duplex alone. Cross-sectional imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) venography is rarely needed or indicated in the workup of vTOS. Catheter-based venography is the key confirmatory imaging study to document the extent of vTOS and leads to the initial recommended therapeutic strategy of thrombolysis and reduction of clot burden.

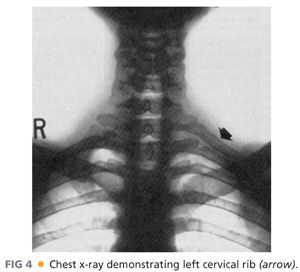

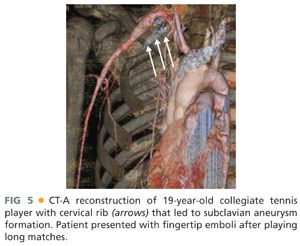

■ Patients presenting with digital ischemia suspicious for aTOS should undergo plain radiographic imaging to assess for a cervical rib (FIG 4). Digital plethysmography of bilateral upper extremities can be performed to visualize blood flow to each finger and can rule out Raynaud’s type etiologies in the differential diagnosis. Wrist–brachial indices should be documented prior to any further intervention to establish baseline flow characteristics. CT-A of the neck and upper extremity in provocative positioning (arms at 180 degrees overhead) provides the most definitive visualization of the affected region, confirming the presence of the cervical rib, delineating the amount of thrombus in the subclavian aneurysm, and documenting the proximal and distal vasculature for operative planning (FIG 5).

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

■ vTOS patients diagnosed with acute axillosubclavian DVT should be anticoagulated with weight-based dosing of unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin. Depending on the resource availability, admission for thrombolysis or urgent referral to a center capable of catheter-directed interventions has been generally accepted as standard of care.3 There are patients that are simply put on anticoagulation that get referred much later (more than 2 weeks) due to lack of recognition of the TOS etiology of the DVT and this leads to a diminished success rate of thrombolysis.4

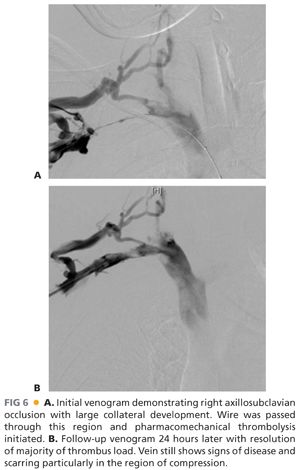

■ Successful thrombolysis involves a combination of chemical and mechanical thrombectomy and is often quite effective in decreasing clot burden and reducing long-term sequelae of upper extremity DVT (FIG 6A,B). Technical details of thrombolysis are well described and can be performed with minimal morbidity.5

■ Definitive therapy for vTOS after thrombolysis involves thoracic outlet decompression, consisting of anterior and middle scalenectomy, resection of the subclavius tendon, 1st rib resection, and venolysis or venous reconstruction. Timing of definitive surgery after thrombolysis is somewhat controversial and is limited by anecdotal reports and various surgeon biases.6 Successful outcomes can be achieved with definitive thoracic outlet decompression performed during the same hospitalization as the thrombolysis7 and up to 3 months later with nonresolution of mild venous obstructive symptoms,5 leading some to adopt a more selective approach for offering rib resection. This lack of consensus provides some flexibility in offering definitive surgery as many of these young patients are often student-athletes and cannot miss certain periods of the school year. Management of anticoagulation during this time also impacts decisions about planning surgery, as intolerance to blood thinners or difficulty with maintaining adequate anticoagulation can affect the urgency of the required definitive decompression. If there is a delay in scheduling definitive rib resection, a duplex immediately prior to surgery after successful thrombolysis is important to document the status of the vein during the immediate pre-operative period.

■ In contradistinction to the numerous pathways for vTOS surgery planning aTOS in the presence of an ipsilateral cervical rib and subclavian aneurysm presents a strong indication for definitive surgical intervention. Preoperative planning consists mainly of ensuring adequate and healthy vasculature proximal and distal to the diseased segment and determining a bypass route that is reasonable. Extraanatomic bypass via a carotid–subclavian or carotid–axillary with interval ligation may be necessary, depending on the size and length of the subclavian aneurysm and thrombus. Direct repair of the subclavian aneurysm with interposition grafting can be accomplished only when there is a short segment of disease that limits itself to the visualized region in the supraclavicular fossa. The preoperative CT-A provides the best road map to help decide amongst these reconstructive strategies. Endovascular techniques of the subclavian artery such as stent grafting in the setting of aTOS are generally not recommended, given the age of the typical patient, the compression that can occur from scarring even after cervical or 1st rib decompression, and the likely desire to resume prior activities that often brought about these symptoms in the postoperative period.

Positioning

■ vTOS decompression will often involve an infraclavicular incision (some prefer only this incision; some prefer a paraclavicular approach; still others prefer transaxillary), which is facilitated by positioning the patient with a small bump between the shoulder blades and in a “head up” position of 30 degrees. The affected arm is prepped out and placed in a stocking on the side of the patient to allow full movement during the case. This affords the anterior visualization of the 1st rib and particularly the subclavius tendon and costoclavicular ligament for safe and effective decompression. The entire ipsilateral neck, shoulder, arm, and anterior chest wall are prepped into the field as well as a region on the lateral chest wall should there be a small pneumothorax postprocedure.

■ aTOS decompression with cervical rib is most often performed with a supraclavicular approach. When arterial reconstruction is planned, preparations should be made for saphenous or femoral vein harvesting.