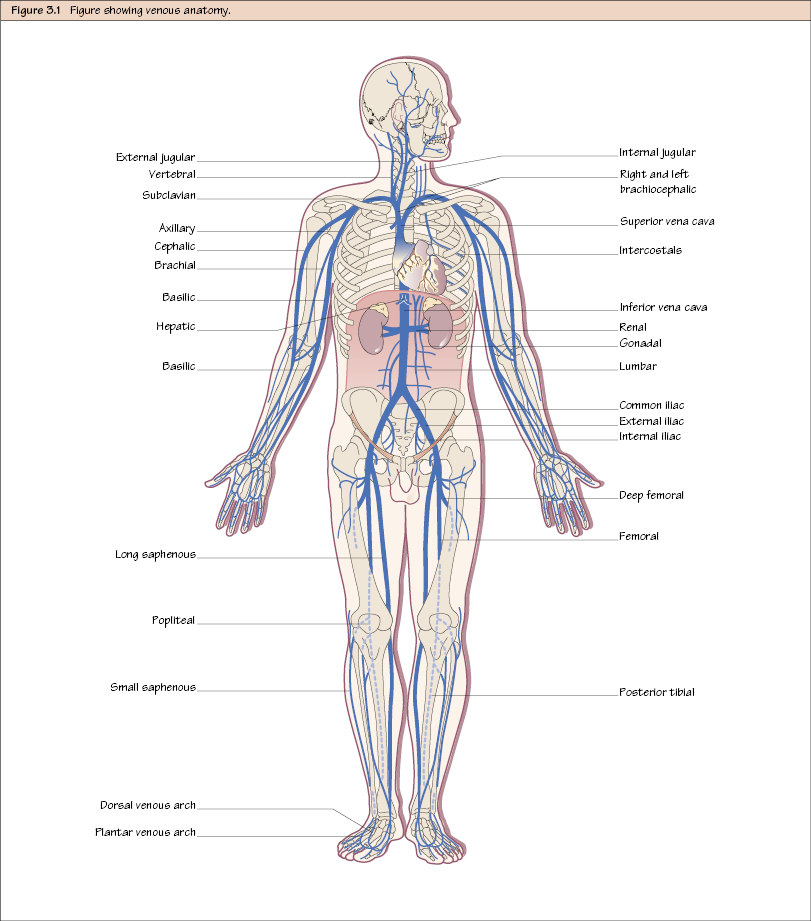

Venous Anatomy You will need to remember the venous system in the leg because this is the most common site of venous problems (e.g. varicose veins and deep venous thrombosis). However, for vascular access the upper limb and central veins are very important. The venous circulation is different from the arterial system in the following ways: Blood drains from the foot into the dorsal venous arch, which is often visible on the dorsum of the foot. The lateral end of the dorsal venous arch continues as the short saphenous vein and passes posteriorly to the lateral malleolus, lying with the sural nerve. It passes up the posterolateral side of the calf in the subcutaneous fat towards the midline of the leg. It then turns deeply to pierce the deep fascia and continues on to join the popliteal vein at an oblique angle, the join being called the saphenopopliteal junction

Venous Anatomy

Lower Limb

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree