Vena Cava Resection for Renal Cell Carcinoma

R. Clement Darling III

Chin Chin Yeh

John B. Taggert

In 4% to 10% of renal cell carcinoma patients the tumor extends beyond the renal vein into the inferior vena cava (IVC). In the absence of metastases, surgery excision offers a 69% 5-year survival. However, there are many patients who because of leg swelling or venous congestion, pain or other constitutional symptoms, require palliative resection. Contraindications are usually based on patient comorbidities and whether they can tolerate the procedure.

Adequate staging to identify the grade and extent of the tumor is essential, which includes assessing the involvement of the IVC. All patients obtain some abdominal imaging such as CTA or MRA. This allows visualization of how extensive the IVC is affected, such as involvement of the renal veins, hepatic veins, or atrium. Venous extension may also be suspected clinically if the patient has extensive bilateral lower extremity edema. A varicocele that does not collapse when supine, dilated superficial abdominal veins, pulmonary embolus, right atrial mass, a nonfunctioning kidney, and proteinuria all suggest IVC thrombus.

The arterial supply of renal cell carcinoma can be quite elaborate and a preoperative angiogram can be useful in delineating that vasculature. Angiograms are not only diagnostic, but can also help reduce intraoperative blood loss when preoperative embolization is done to shrink the tumor and facilitate excision.

Another modality that has proved effective in evaluating the cephalad extent of the tumor is intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography. It allows the surgeon to visualize how far cephalad the IVC thrombus extends, particularly in relation to the hepatic veins. The surgeon can use this information to decide whether cross-clamping below the hepatic veins is feasible, thereby minimizing the physiological effect of clamping the IVC.

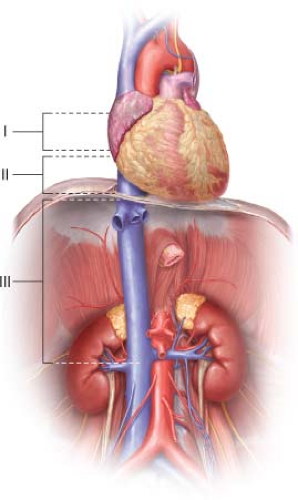

Tumor involvement of the IVC can be divided in three levels (Fig. 15.1): Level 1 is up to the hepatic veins; level 2 is into the suprahepatic cava; and level 3 is extension

into the atrium. Patients who have level 3 tumors may require cardiopulmonary bypass during the time of operation; however, in our experience, the majority of the time cardiopulmonary bypass is not needed as we are able to mobilize the tumor by opening the diaphragm and performing a median sternotomy. This flattens the tumor and pulls it out of the atrium into the suprahepatic cava. Tumors that are nonmobile are usually the ones in which cardiopulmonary bypass is needed so that atrium may be opened and the tumor extracted. These tumors should be resected en bloc with the kidney if possible. If the procedure is palliative, the renal vein can be stapled and the IVC tumor taken out separately. Special care must be maintained at all times to minimize cephalad embolization or embolization into the contralateral vein.

into the atrium. Patients who have level 3 tumors may require cardiopulmonary bypass during the time of operation; however, in our experience, the majority of the time cardiopulmonary bypass is not needed as we are able to mobilize the tumor by opening the diaphragm and performing a median sternotomy. This flattens the tumor and pulls it out of the atrium into the suprahepatic cava. Tumors that are nonmobile are usually the ones in which cardiopulmonary bypass is needed so that atrium may be opened and the tumor extracted. These tumors should be resected en bloc with the kidney if possible. If the procedure is palliative, the renal vein can be stapled and the IVC tumor taken out separately. Special care must be maintained at all times to minimize cephalad embolization or embolization into the contralateral vein.

All macroscopic tumor should be removed from the IVC and any of its branches at the time of surgery. Total excision is the best method of curative resection for this tumor. In some cases, we mark the edges of the vena cava resection to look for microscopic tumor extension. This lateral approach does increase the risk of having to patch or reconstruct the IVC, which can lengthen the procedure. However, closure of the IVC is usually performed while the pathologist is evaluating the microscopic specimens. We have found that macroscopic evaluation correlates well with microscopic evaluation.

Although it is commonly thought that these tumors tend to float in the vena cava, this is not always the case. It is difficult to assess whether the vein wall is involved; so at the time of surgery, one must be prepared not only to do the local resection with primary reconstruction but also to have different options for patching, replacing, or ligating the vena cava while preserving flow to the contralateral renal veins. Typically in our experience, PTFE and bovine pericardium have been excellent in patching the vena cava, and PTFE has worked well when we have had to bypass involved segments.

Positioning

The patient is placed in the supine position and either a long midline incision or, more commonly, a chevron bisubcostal incision is made. In those patients who have extension

of tumor into the suprahepatic cava and especially the atrium, a Mercedes extension or even a complete median sternotomy may be needed to gain access to the pericardium.

of tumor into the suprahepatic cava and especially the atrium, a Mercedes extension or even a complete median sternotomy may be needed to gain access to the pericardium.

Techniques

There are three major concerns when drawing up the perioperative surgical plan: (1) How to minimize embolization of the tumor, (2) how to minimize blood loss, and (3) how to minimize engorgement of the organs while maintaining preload to the right side of the heart and controlling hypertension during vena cava clamping.

Prior to the vascular portion of the operation, the urologist has dissected out the kidney and made it fully mobile. At this point, either the vascular surgeon or the urologist can transect the renal artery, which allows one to bring the tumor and renal vein anteriorly. This allows complete visualization of the venotomy. Surgical approach is dictated by the level of tumor involvement. For level 1 tumors that are below the diaphragm and specifically below the hepatic veins, dissection is relatively straightforward. Suprarenal control is obtained by sharp dissection and umbilical tape is placed around the vena cava. Special care must be taken to not disrupt any intercostals and to identify them before opening up the vena cava as this can precipitate significant blood loss. Control also needs to be obtained over the contralateral renal vein and the infrarenal vena cava. Left-sided tumors are often more challenging due to the large lumbar branch and left renal vein traveling posteriorly. Unless a full Maddox maneuver is performed, and the colon is brought over, those branches may be in the way when doing the venacavotomy. Alternatively, in patients with left renal tumors, it is sometimes difficult to visualize the left side of the vena cava for venectomy. We incise the right (lateral) side of the vein first, remove the loose tumor, and then carefully excise the left wall under direct vision.

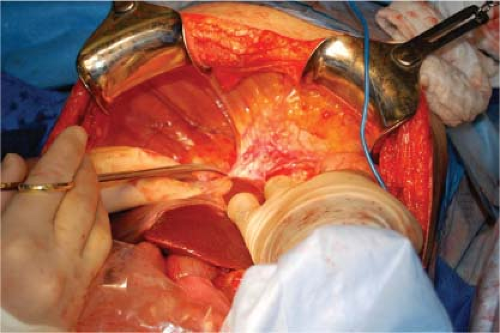

To mobilize the liver for tumor resection, the coronary ligament and the right and left triangular ligaments are usually divided (Fig. 15.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree