Long-term oral anticoagulation (OAC) prevents recurrent thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and stroke, but it also increases bleeding risk. An outpatient bleeding risk index (OBRI) may help to identify patients at high risk of bleeding complications. The aim of this study was to evaluate the predictive value of OBRI in patients with OAC undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). In addition, we analyzed the impact of OBRI on treatment choices in this patient group. Four hundred twenty-one patients with OAC underwent PCI at 6 centers in Finland. Complete follow-up was achieved in all patients (median 1,276 days). Sixty-four patients (15%) had a low bleeding risk (OBRI 0), 319 patients (76%) moderate bleeding risk (OBRI 1 to 2), and 38 (9%) high bleeding risk (OBRI 3 to 4). OBRI had no significant effect on periprocedural or long-term antithrombotic medications, choice of access site, or stent type. During follow-up, the incidence of major bleeding increased (p = 0.02) progressively with higher OBRI category (6.3%, 14.1%, and 26.3%, respectively). Similarly, mortality was highest in patients with high OBRI (14.1%, 20.7%, and 39.5%, p = 0.009, respectively), but rates of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events were comparable in the OBRI categories. In conclusion, bleeding risk seems not to modify periprocedural or long-term treatment choices in patients after PCI on home warfarin. In contrast, patients with high OBRI often have major bleeding episodes and this simple index seems to be suitable for risk evaluation in this patient group.

Because there are no data on how bleeding risk affects clinical decisions and prognosis in patients on long-term oral anticoagulation (OAC) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), we assessed the value of an outpatient bleeding risk index (OBRI) in predicting bleeding events and prognosis during long-term follow-up after PCI and investigated whether bleeding risk modifies contemporary treatment choices in this patient group.

Methods

This retrospective study is 1 part of a study in progress to assess thrombosis and bleeding complications of cardiac procedures in western Finland. This substudy is based on 421 consecutive patients on home warfarin treatment who underwent PCI in 6 Finnish hospitals from 2002 to 2006. Baseline and in-hospital data were provided by local institutional clinical registries that prospectively collect information in computerized databases. Furthermore, nonblinded review of full medical records of eligible patients was performed to determine perioperative antithrombotic strategies and incidence of in-hospital complications.

All patients were followed by office visits or telephone interviews by treating physicians, with the last contact from September 2008 to February 2009. Major bleeding episodes and major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCEs) were recorded. In addition, all data available from hospital records, institutional electronic clinical database, and referring physicians were checked at the end of the follow-up period to record the medication at the time of MACCEs and major bleeding. Hospital records and death certificates from the Central Statistical Office of Finland were used to record and classify deaths.

The Congestive Heart Failure, Hypertension, Age >75, Diabetes Mellitus, and Prior Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack (CHADS 2 ) score, which quantifies the annual stroke risk for patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, was recorded for all patients. Bleeding risk was evaluated retrospectively by OBRI, which considers history of stroke, age >65 years, history of gastrointestinal bleeding, presence of ≥1 co-morbid condition (recent myocardial infarction [MI], renal insufficiency, severe anemia, or diabetes) to stratify patients into 3 risk groups. Based on this classification a patient is considered at low (0 risk factor), moderate (1 risk factor or 2 risk factors), or high (3 to 4 risk factors) risk for bleeding. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees of the co-ordinating Satakunta Central Hospital (Pori, Finland) and participating hospitals.

Major bleeding was defined as a decrease in blood hemoglobin level >4.0 g/dl, need for transfusion of ≥2 U of blood, need for corrective surgery, occurrence of an intracranial or retroperitoneal hemorrhage, or any combination of these. A MACCE was defined as the occurrence of any of the following during follow-up: death, Q-wave or non–Q-wave MI, target vessel revascularization, stent thrombosis, or stroke. MI was diagnosed when a increase in myocardial injury marker level (troponin I or T) was detected with symptoms suggestive of acute MI. For diagnosis of myocardial reinfarction, a new increase >50% above the baseline injury marker level was required. Periprocedural MI was not routinely screened, but if procedural MI was suspected, a troponin level >3 times the normal 99th percentile level was required for the diagnosis. Target vessel revascularization was defined as any reintervention driven by any lesion located in the stented vessel. Stent thrombosis was diagnosed with angiographic evidence of thrombotic vessel occlusion or thrombus within the stent or in autopsy. Stroke was defined as an ischemic cerebral infarction caused by a thrombotic occlusion of a major intracranial artery or intracerebral hemorrhage.

Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages and were compared by chi-square or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. Continuous variables are presented as means ± SDs and differences between study groups were tested with analysis of variance and a Bonferroni correction was performed to account for multiple comparisons. MACCEs, major bleeding, and all-cause death were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier survival curves during follow-up and differences between groups were compared using log-rank test. After univariate analyses, logistic multivariable regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors for major bleeding and MACCEs in the entire study population. Because of multiple testing, only variables with a 2-sided p value <0.05 in univariate analysis were accepted for the model. Results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

Results

Atrial fibrillation (72% of entire cohort) was the most frequent indication for OAC. Most patients were in the moderate bleeding risk group and high bleeding risk (OBRI 3 to 4) was detected in 38 patients (9%). These patients with high bleeding risk differed from patients with a lower OBRI score with respect to gender, smoking history, and hypertension plus clinical features involved in OBRI classification ( Table 1 ).

| Variable | OBRI 0 (n = 64) | OBRI 1–2 (n = 319) | OBRI 3–4 (n = 38) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58 ± 8 | 71 ± 7 | 74 ± 6 | 0.001 |

| Men | 56 (88%) | 233 (73%) | 26 (68%) | 0.03 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 42 (66%) | 245 (77%) | 15 (39%) | <0.001 |

| Family history of coronary artery disease | 26 (41%) | 96 (30%) | 7 (18%) | 0.06 |

| Hypertension | 27 (42%) | 210 (66%) | 31 (82%) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (5%) | 93 (29%) | 26 (68%) | <0.001 |

| Smoker | 25 (39%) | 78 (24%) | 7 (18%) | 0.03 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 42 (66%) | 225 (71%) | 28 (74%) | 0.65 |

| Heart failure | 13 (20%) | 68 (21%) | 6 (16%) | 0.73 |

| Stroke | 4 (6%) | 60 (19%) | 28 (74%) | <0.001 |

| Renal disease | 2 (3%) | 20 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 0.43 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 25 (39%) | 112 (35%) | 14 (37%) | 0.83 |

| Previous percutaneous coronary intervention | 8 (13%) | 48 (15%) | 2 (5%) | 0.24 |

| Previous coronary artery bypass grafting | 7 (11%) | 74 (23%) | 6 (16%) | 0.06 |

| CHADS 2 score | 0.9 ± 0.8 | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 2.8 ± 1.2 | <0.001 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 45 ± 19 | 43 ± 21 | 51 ± 15 | 0,06 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 28 (44%) | 160 (50%) | 20 (53%) | 0.59 |

| Femoral access | 47 (73%) | 248 (78%) | 29 (76%) | 0.75 |

| Drug-eluting stents | 32 (50%) | 141 (44%) | 19 (50%) | 0.59 |

| Stent diameter (mm) | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 0.5 | 0.23 |

| Stent length (mm) | 25.2 ± 16.9 | 22.0 ± 11.0 | 22.5 ± 11.4 | 0.13 |

Bleeding risk had no significant effect on selection of access site or use of drug-eluting stents. Similarly, in-hospital antithrombotic treatments were not modified in patients with high bleeding risk ( Tables 1 and 2 ). At discharge, triple therapy was the most often used strategy and OBRI score did not modify treatment strategies after PCI. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in duration of aspirin and clopidogrel treatments or triple therapy between bleeding risk groups ( Table 2 ).

| OBRI 0 (n = 64) | OBRI 1–2 (n = 319) | OBRI 3–4 (n = 38) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| During index hospitalization | ||||

| Enoxaparin | 36 (56%) | 189 (59%) | 24 (63%) | 0.79 |

| Heparin | 7 (11%) | 32 (10%) | 5 (13%) | 0.83 |

| Clopidogrel | 57 (89%) | 288 (90%) | 32 (84%) | 0.51 |

| Aspirin | 50 (78%) | 275 (86%) | 33 (87%) | 0.24 |

| Fibrinolytic therapy | 1 (1.6%) | 5 (1.6%) | 3 (8%) | 0.04 |

| Glycoprotein inhibitors | 15 (23%) | 99 (31%) | 10 (26%) | 0.43 |

| Bivalirudin | 0 | 11 (3%) | 2 (5%) | 0.25 |

| At discharge | ||||

| Aspirin + clopidogrel | 9 (14%) | 52 (16%) | 5 (13%) | 0.82 |

| Aspirin + clopidogrel + oral anticoagulation | 34 (53%) | 194 (61%) | 22 (58%) | 0.48 |

| Oral anticoagulation + aspirin | 7 (11%) | 29 (9%) | 6 (16%) | 0.41 |

| Oral anticoagulation + clopidogrel | 14 (22%) | 42 (13%) | 5 (13%) | 0.19 |

| Aspirin monotherapy | 0 | 1 (0.3%) | 0 | NS |

| Clopidogrel monotherapy | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Oral anticoagulation monotherapy | 0 | 1 (0.3%) | 0 | NS |

| During follow-up | ||||

| Duration of clopidogrel therapy (months) | 5.0 ± 6.2 | 4.9 ± 7.4 | 4.0 ± 5.0 | 0.73 |

| Duration of triple therapy (months) | 3.0 ± 2.8 | 3.4 ± 2.9 | 3.4 ± 3.3 | 0.77 |

Fifty-nine patients had major bleeding episodes during follow-up (mean 40 months). Seven of these episodes were fatal and these events were intracranial bleedings. None of the fatal bleeds occurred during triple therapy; 2 episodes occurred during warfarin monotherapy and 5 during dual therapy with warfarin and aspirin. Two fatal bleeding episodes occurred during the index hospitalization. In 2 cases the international normalized ratio was supra-therapeutic and in 3 cases death occurred before international normalized ratio measurements were obtained. Three patients developed several (3 to 6) major bleeding episodes during follow-up.

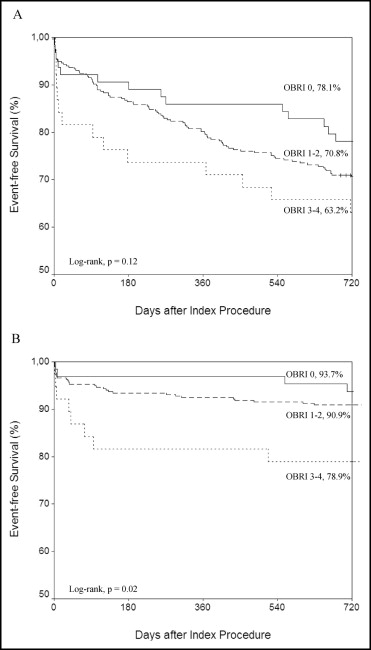

Outcome events during follow-up are presented in Figure 1 and Table 3 . The incidence of major bleeding increased significantly (p = 0.02) according to the OBRI score and 26% of patients in the high bleeding risk category had a major bleeding event during the follow-up period. Most bleeding events occurred shortly after PCI ( Figure 1 ), but in-hospital bleeding events were similar in the OBRI categories. Risk of major bleeding was ≥10 times higher during triple therapy than during warfarin treatment ( Figure 2 ). Addition of 1 antiplatelet agent to OAC did not increase the risk of major bleeding compared to OAC only ( Figure 2 ). All-cause mortality was higher in patients with a high bleeding risk index (p = 0.009), but there were no significant differences in rates of MACCE, MI, stroke, or stent thrombosis between study groups. Mortality was higher (53% vs 16%, p <0001) in patients with a major bleeding event than in those without such an event.